In 1923 Josef was appointed Master of the preliminary course at the Bauhaus. His approach to teaching sought to marry a proficiency in craftsmanship and industry. From a young age, Josef had developed a deep appreciation for the meticulous, skilled labour of the blacksmiths, cobblers and joiners in the workshops that dominated his neighbourhood in Bottrop. Through observation he had learnt that a profound knowledge and experience of materials and processes was essential to making work of the highest quality. He began by asking his students to test the ‘dormant possibilities’ of a material such as paper, foil or wire, to explore both its external, aesthetic potential and its internal, structural potential. This process allowed the students to build an acute sense of ‘tactile scales’—between hard and soft, smooth and rough, or warm and cold.

After the Bauhaus closed in 1933, Josef’s reputation as a vanguard of experimental education provided the couple with the plan they needed to escape a rapidly worsening situation in Germany. In 1934, the couple were invited to join the faculty of a new experimental school in North Carolina, Black Mountain College. Anni and Josef took the influence of the Bauhaus across the Atlantic to America and were instrumental in fostering progressive ideas in education and art among a generation of younger artists. Josef’s classes at Black Mountain and later Yale University were physical and mental exercises that encouraged students to conduct experiments such as moving pieces of coloured paper around in different arrangements, examining the resulting effects and associations created between different combinations.

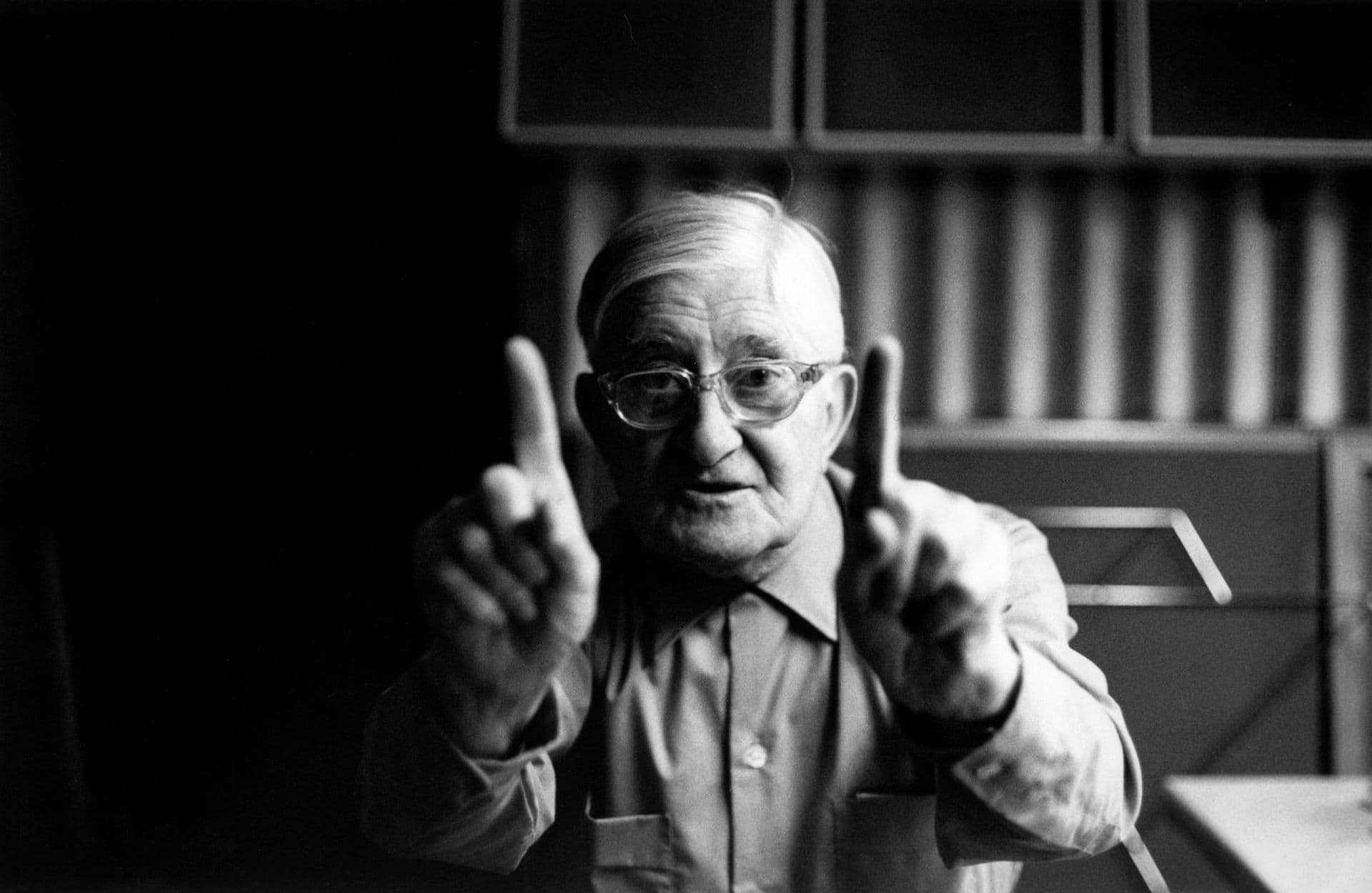

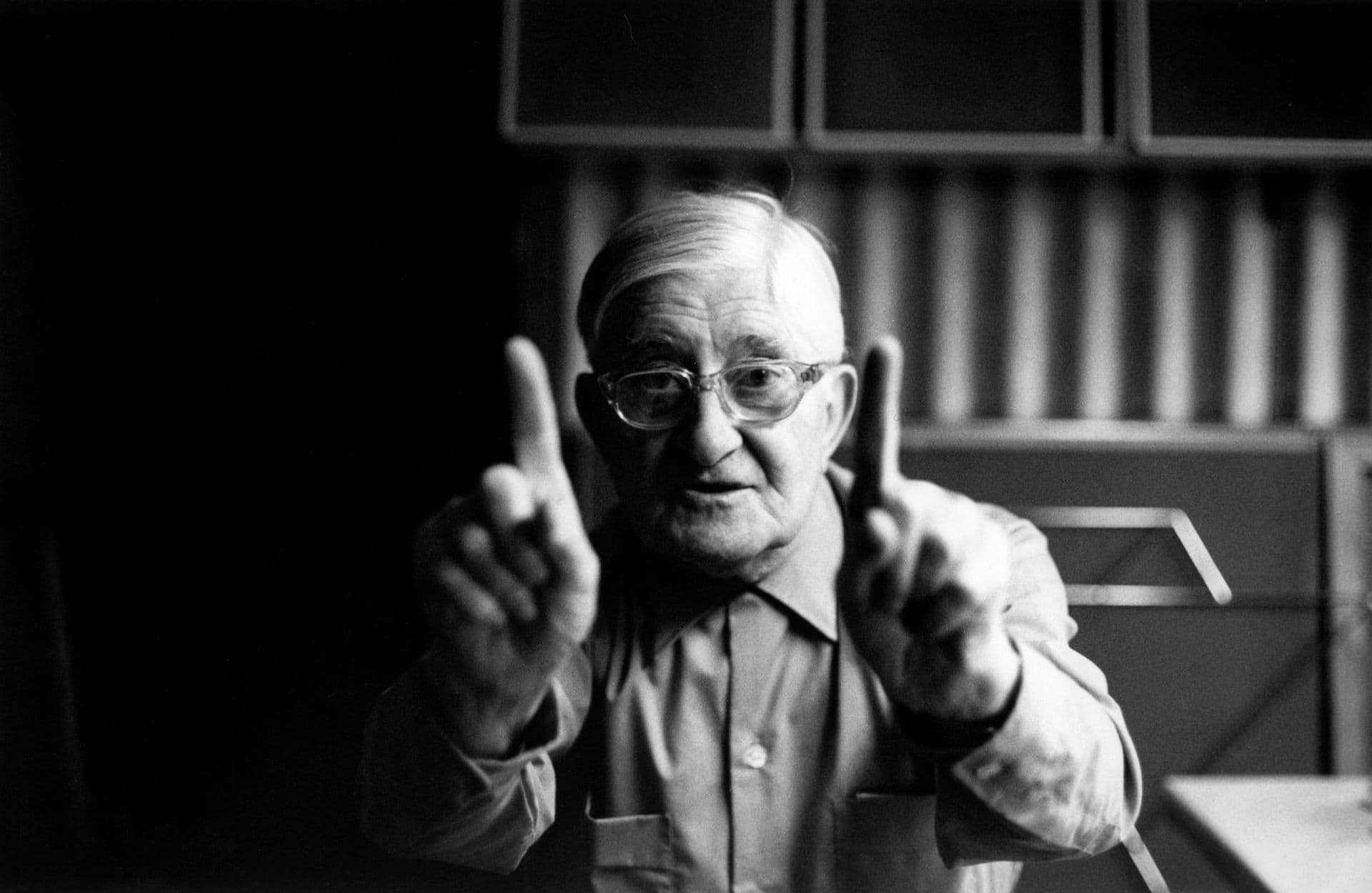

This unconventional approach to teaching can be seen in the following footage of one of Josef Albers’ classes at Yale University in 1955.

Watch this video on your device below.