Jenny Watson

born 1951 Narrm / Melbourne 1951Jenny Watson by Sally Brand

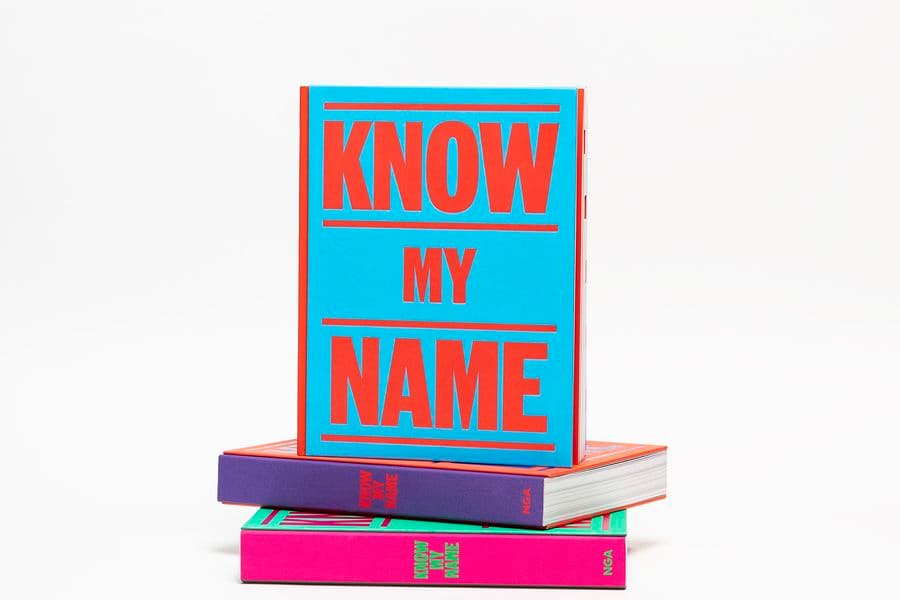

Excerpted from the Know My Name publication (2020).

There was a point that I realised, as a female artist I had a lot of sources to draw upon. There were things that couldn’t be done by a male artist because it would have been totally inauthentic … This decision was probably in its finest hour when I began to use a self image.(1)

A large syringe stands on needle point at the centre of Jenny Watson’s Self portrait as a narcotic 1989. Inside the syringe the artist’s white‑stockinged legs languish in the air and her flaming red hair laps up one side of the vial. Like Alice down the rabbit hole, another alter ego the artist has deployed in her paintings, Watson has fallen into a mixed‑up world. Around the syringe, letters are askance, jumbled across the surface in different fanciful styles like a schoolgirl might decorate the margins of her diary. The painting’s title offers the key, but it is not without some puzzling before the letters can be read as words. Overall, the work is raw, loose, emotional and it is this honest vulnerability, both powerful and complex, that has established Watson as one Australia’s leading artists over the past four decades.

In the early 1970s when Watson was studying at Melbourne’s National Gallery School, hard‑edge colour abstraction was considered the ‘serious’ art form.(2) The National Gallery of Victoria’s 1968 The field exhibition celebrated art that valued colour, form and impersonal flat surfaces above all else. In this context, Watson chose a different approach by adopting in her early practice a style of photorealism. Her pencil drawings were included in the 1974 exhibition The supernatural natural image that pronounced a post‑The field art historical breakthrough under the banner of ‘new realism’.(3) Watson found early success with her photorealist works, exhibiting alongside German artist Gerhard Richter in the 1977 nationally touring exhibition Illusion & reality.

Never satisfied with the status quo, an approach validated by the feminist and punk movements of the 1970s with which Watson had also been involved, she moved away from photorealism, using her skills to reproduce roughly textured painted pages from newspapers and magazines. Watson’s pop‑punk appropriation paintings brought her practice further attention from curators and critics both in Australia and overseas, however this period of her practice was also short‑lived. While appropriation art became one of the most critically acclaimed practices in Australia in the 1980s, Watson relentlessly followed her own path. Today her personal style continues to feature self‑image and text often on unstretched, raw fabrics, painted with pigments and adorned with ribbons, horsehair, glue and sequins. Watson’s conceptual approach to painting has led to international recognition and her commitment to sharing her own voice and perspective has paid dividends.(4)

(1) Sally Brand, ‘Painted pages: edited notes of an interview with Jenny Watson conducted at the University Art Museum on the afternoon of Wednesday 28 May, 2003’, in David Pestorius (ed), In conversation, University Art Museum, University of Queensland, Brisbane, 2003, p 45.

(2) Paul Taylor, ‘Jenny Watson’s “Mod”ernism’, Art International, vol 24, no 5–6, 1981, p 214.

(3) Ron Radford and Katherine Rumley, The supernatural natural image, Ballarat Fine Art Gallery, Ballarat, 1974, np.

(4) Benedikt Stegmayer, Confessions: Autobiografie als fiktives konstrukt: Jenny Holzer, Jenny Watson, Tracy Emin, Verlag fur zeitgenossische Kunst und Theorie, Berlin, 2015, pp 41–69.

Citation: Cite this excerpt as: Brand, Sally. "Jenny Watson" in N Bullock, K Cole, D Hart & E Pitt (eds), Know My Name, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 2020, pp 364–365.

SALLY BRAND is is Programs Manager, Curatorial and Educational Services, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra.

//know-my-name/media/dd/images/64184.ba24299.jpg)