The world of fine art printmaking was transformed in the second half of the twentieth century in what is referred to as the American Print Renaissance.1 In turn, print disciplines, particularly lithography and screenprinting, transformed the world of art, by re-engaging artists with the processes of making prints. Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg were key artists in the American Print Renaissance and their thoughtful engagement with printmaking would impact all aspects of their practice. Ideas derived from the actions of printing, such as pressure, transference and stencilling, informed their work, as did the implications of reproduction, the reorientation of the picture plane and the materials used for printmaking.

Kenneth Tyler operating his custom-designed hydraulic lithography press during edition printing of Nicholas Krushenick's Fairfax and mustard, at Gemini Limited print workshop, Los Angeles, California, September, 1965. Kenneth E. Tyler Collection archive, NGA Study Collection.

A print revival

In the first half of the twentieth century, in the United States, printed material was abundant in a variety of commercial applications. Newspapers, product packaging and advertisements were ubiquitous. Print techniques such as offset lithography, etched printing plates and screenprinting were relied on to reproduce images economically and accurately. The close association of printed material with commerce meant that many artists would eschew these reproductive mediums for others such as painting. It was no coincidence that lithography studios for fine arts had almost entirely disappeared from the United States by the early 1950s. When artists sought out small-scale lithography at this time, they could find such studios only in Europe. This changed around 1960, when the artists June Wayne and Garo Antreasian founded Tamarind Lithography in Los Angeles, with the purpose of reviving this art form. At the same time, Tatyana Grosman’s fledgling Universal Limited Art Editions (ULAE) in New York was beginning to expand its work to create original prints with artists. Against this backdrop, an ambitious young art student, Kenneth Tyler, joined Tamarind Lithography in 1963, moving from his native Chicago to Los Angeles to undertake an apprenticeship with Antreasian. Here Tyler would apply his technical know-how, helping to find substitute printing plates made from a ball-grained aluminium that could work just as well as the increasingly rare lithographic limestone. Tyler’s enthusiasm for both the art and science of lithography meant that within a year he became the workshop’s technical director, though he felt progressively more limited by the scale and ambition that he encountered at Tamarind. Just over two years later, in 1965, he decided to open his own workshop, Gemini Limited, which would soon become known as Gemini Graphic Editions Limited (Gemini GEL). Replete with a new hydraulic press that Tyler designed to achieve more consistent colours in print, this new workshop would reshape the printmaking landscape. What made Tyler’s workshop unique was an artist-led philosophy, where instead of confining projects to the restrictive traditions of printmaking, he actively sought artists that would ‘make demands on the medium’2 and engineer the solutions to their creative ambitions. Two artists that would push the boundaries of the medium with Tyler during these early years were Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns.

Print techniques in Johns’s and Rauschenberg’s early practices

Jasper Johns, Figure 1 1955, encaustic and newspaper on canvas, 44 x 35 cm. Collection of Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Acc# ML 01652. Image courtesy of Museum Ludwig, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021

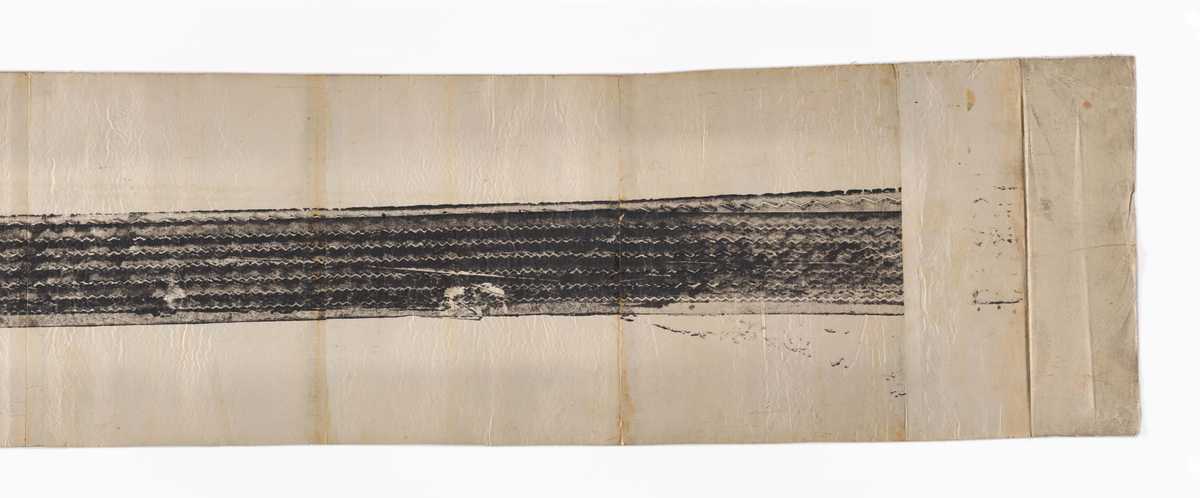

Robert Rauschenberg, Automobile tire print 1953 (detail), paint on 20 sheets of paper, mounted on fabric, 41.9 x 726.4 cm. Collection of San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, purchase through a gift of Phyllis C. Wattis. Image courtesy of SFMOMA, © Robert Rauschenberg / Copyright Agency 2022, photographer: Don Ross

Printmaking processes were intuitively part of the early artistic practice of both Rauschenberg and Johns. Before either artist had worked in print workshops, they shared an interest in using everyday objects as rudimentary printing matrices to impress an image on a receptive surface: Jasper Johns would use readymade stencils, which are a form of simple print matrix, to create his paintings such as Figure 1 1955; while Robert Rauschenberg would create works such as Automobile tire print 1953, using housepaint and a car to create a monotype print of a car tire’s path on paper. Both artists displayed an incredible openness to using commonplace objects as stamps: Jasper Johns recalled that in 1959 they were invited to paint a canvas as part of one of the early ‘Happenings’ organised by Allan Kaprow. Here, Rauschenberg ‘discarded his brush [and] simply dipped the top of the jar into paint and then printed it onto fabric’.3 Similarly, Johns would create early assemblages, for instance Memory piece: Frank O’Hara 1961–70, which demonstrates the impression of a cast metal foot into sand. The action of bringing the metal foot into physical contact with the impressionable surface of sand is analogous to making a print, and, as the title of this work demonstrates, Johns saw a link between making an impression and the idea of memory. This conceptual engagement with the actions of print distinguished both Johns and Rauschenberg from artists who saw printmaking simply as a secondary art form and a means of commercial reproduction. As Jasper Johns said in 1977: ‘Prints are no less important [than painting] to me. In them I’m able to use images and ideas I work over in painting and subject them to transformation. It’s a different physique entirely.’4

Pressure, transference and stencilling: the body

Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns made their first prints with master printer Kenneth Tyler at his Los Angeles workshop, Gemini GEL, within thirteen months of each other. Rauschenberg was the first, starting in February of 1967; Johns began in March of 1968. Although it is not immediately obvious, the thematic focus of their first prints at Gemini GEL was on the human body: Rauschenberg’s Booster and 7 studies print series would centre on self-portraiture in the form of his X-rayed body, while Johns would produce his Black numeral series 1968 and Color numerals series 1968–69 that encoded ideas of the body in the numerals 0 through to 9. Later, Johns would investigate signifying the body in other forms in Four panels from Untitled 1972 (colors) in 1973–74. Rauschenberg and Johns explored ideas of pressure, moulding and transference in these works: processes intrinsic to the printed image.

Leo Castelli and Robert Rauschenberg at a gathering, 141 Canal Street, New York, c 8 December 1968. Kenneth E Tyler Collection archive, NGA Study Collection

When Robert Rauschenberg first arrived at Gemini GEL to begin work with Tyler, he encountered a ghostly image of a pair of hands. This was the recently editioned screenprint on plexiglass, Hands 1966, by Dada artist Man Ray, based on one of his famous ‘rayographs’, made using a photographic process where objects are placed on photosensitive paper and exposed to leave an abstracted impression of their form. Rauschenberg was not entirely impressed, as it was a reproduction derived from a photograph. He recalled ‘they hadn’t sufficiently engaged [Man Ray] in the process. My attitude was that the artist should be as involved as possible.’5 Rauschenberg set to work thinking about how printmaking processes could inform his print, a self-portrait titled Booster 1967.

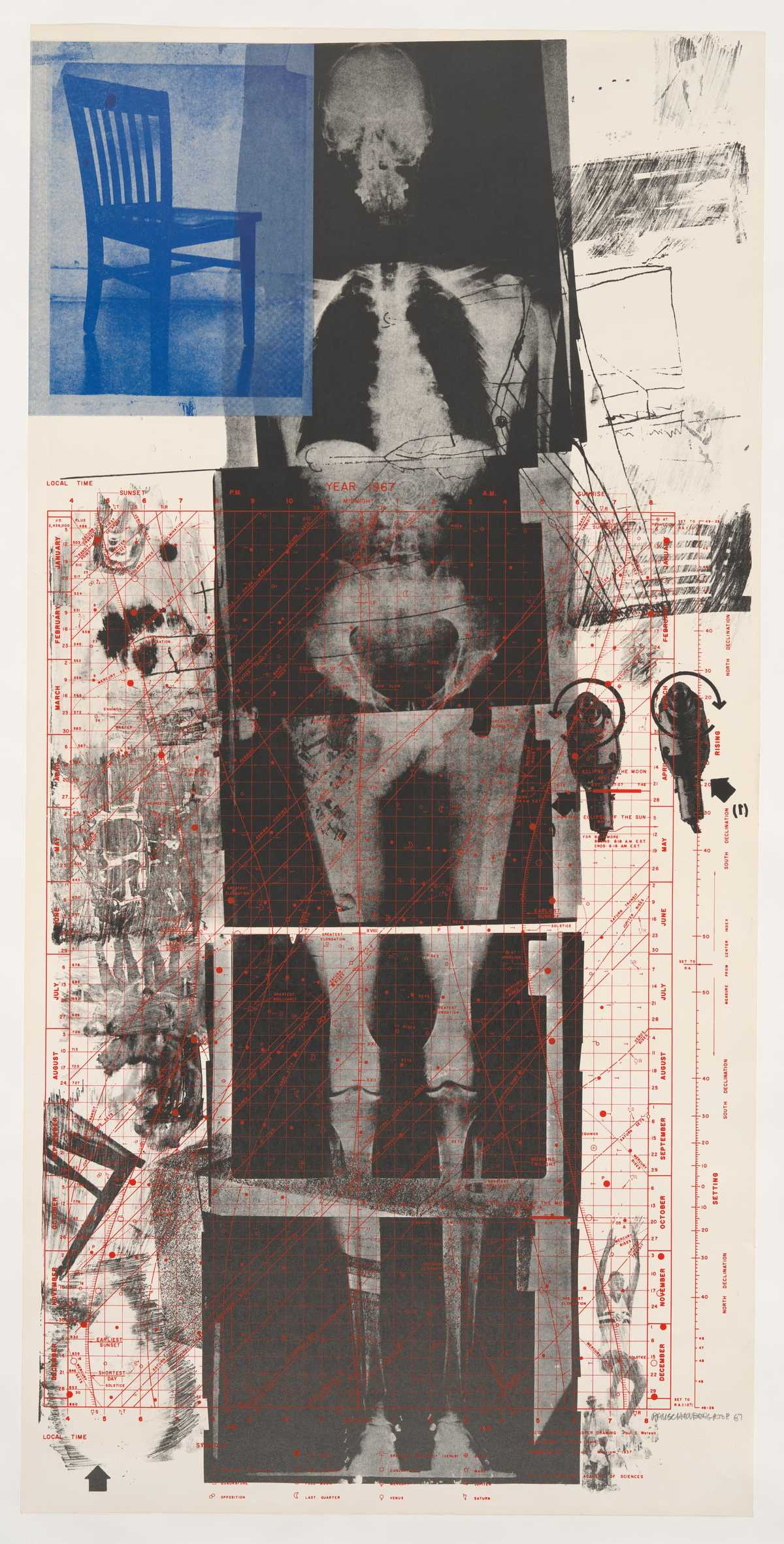

Robert Rauschenberg, Booster 1967 from Booster and 7 studies series, colour lithograph, screenprint, 183 x 89 cm, published by Gemini Graphic Editions Limited, Los Angeles. National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1973. © Robert Rauschenberg / Copyright Agency, 2022

Central to Booster is a life-size X-ray of Rauschenberg. Broken into six different segments from head to toe, this X-ray self-portrait is surrounded with images relating to stress, relationships and seeking guidance, reflecting a time of crisis that Rauschenberg was living through. As scholar Jennifer Robins points out, lithography relies on pressure to transfer an image from the matrix (the lithography stone) to the paper and Rauschenberg was aware of the ability for a printing press to crack thick lithography stones, as it exerts 800–1000 pounds of pressure per square inch.6 Working on Booster at a time when ‘everything was falling apart’,7 Rauschenberg uses self-portraiture to link this pressure to the personal pressure he was under. He applied physical pressure to an image of himself. This idea is reinforced by a hidden image behind the X-ray of a metal stress-testing device that applies pressure to metal samples to test for ‘stress’ and ‘cracking’. The physical processes of making a print conceptually shaped the work, reflecting Rauschenberg’s engagement with the printing process.

Jasper Johns sit in front of his Black numeral series of prints at Gemini GEL, 1968. Kenneth E Tyler Collection archive, NGA Study Collection © photographer, Malcolm Lubliner

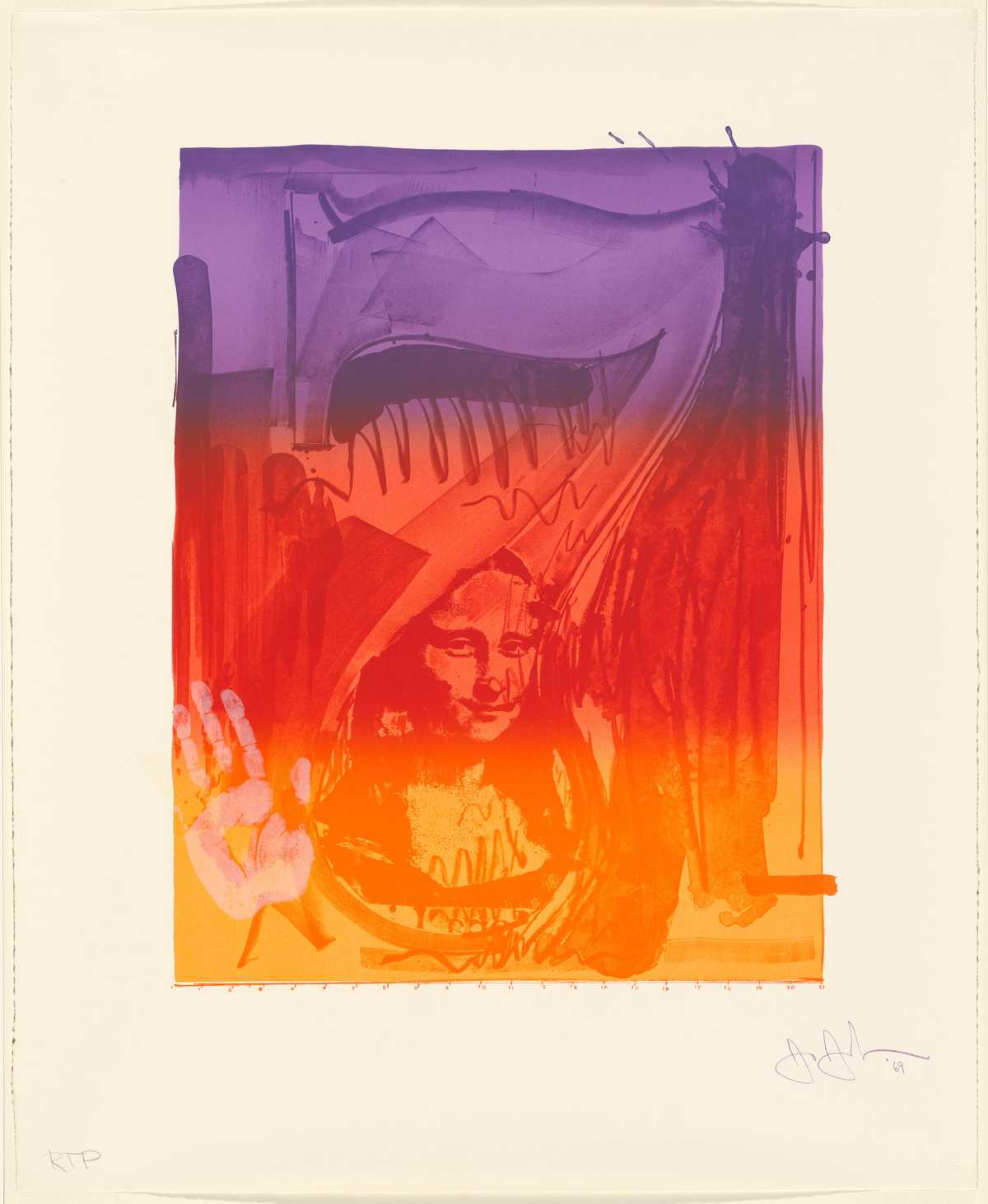

Jasper Johns, Figure 7 from Color numeral series, 1968–69, published by Gemini Graphic Editions Limited, Los Angeles, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1973 © Jasper Johns/Copyright Agency, 2023

When Jasper Johns began working with Tyler in 1968, he revisited a motif from his early paintings in his first series of lithographs: stencilled numerals. As subject matter, numerals are unemotive and don’t appear to express anything more than the idea of the number itself. However, these unassuming works suggest something more. In 1964, Johns had professed his growing interest in ‘a thing’s … becoming something other than what it is’.8 His Black numeral series, followed by the Color numerals series, suggest such a transformation. Johns intended these works to reference the human body. He told the writer Roberta Bernstein that each numeral is titled as a ‘figure’, suggesting the human figure, as he wanted to have a series of figure paintings like the artist Willem de Kooning.9 The lithograph Figure 7 from the Color numerals series is significant in reintroducing figurative imagery into Johns’s work. An iron-on decal of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa is embedded in the work, and adjacent to this is the artist’s own hand-print in white ink. These ‘prints’ within a print point to the relationship between our system of counting and the human body: the ten digits of our number system are derived from the ten digits of our hands, which link our body to this system of knowledge. Johns has also placed a ruler at the base of Figure 7, measuring inches, a unit of measurement originally derived from the width of a man’s thumb. Johns would reflect in 1993 that the incorporation of measures and rulers into his work was his investigation into measures against which the body ‘can or cannot be measured’.10 The implication here is that the human body informs our systems of measurement yet can never itself conform to a standard or a measure. The process of printing stencils incorporates both variable and defined measures—however freely or loosely ink or paint is applied, when printed it also conforms to the stencil’s shape. Johns would remark after making stencilled prints that printmaking ‘suggests things changed or left out’.11

Jasper Johns, Four panels from Untitled 1972 1976, embossed colour lithograph, 4 parts, each 102.8 x 72 cm, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1976 © Jasper Johns / Copyright Agency, 2022

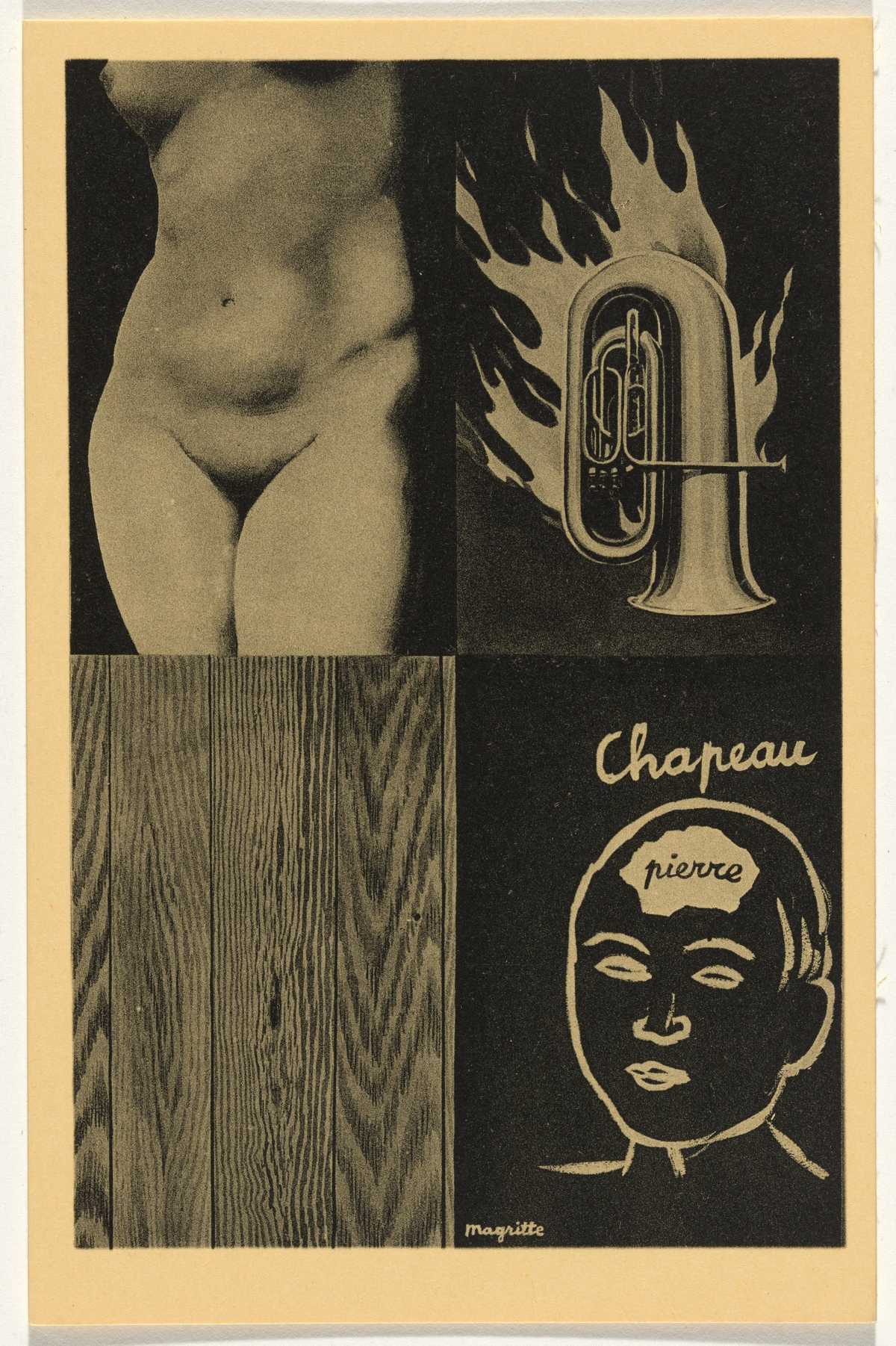

René Magritte, Georges Hugnet, La solution du rébus [The key to the riddle]; from La carte surréaliste - première série [The surrealist postcard - first series], 1937, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, The Poynton Bequest 2010. © Rene Magritte. ADAGP/Copyright Agency.

René Magritte, Belgium 1898–1967 (artist) and Cami Stone, Belgium 1898–1975 (photographer), Five-part painting 1931, gelatin silverphotograph, 24 x 18.2 cm. National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, Purchased 1989. © Rene Magritte. ADAGP/Copyright Agency, 2022

Depictions of the body returned to Johns’s work at Gemini GEL in the 1973–74 embossed colour lithograph Four panels from Untitled 1972 (colors). This four-panel work, based on the painting Untitled 1972, has a hatching pattern in the first panel, while the middle two panels depict flagstone walls and the final panel depicts fragmented body parts suspended between wood planks. This unnerving picture resembles the work of Belgian surrealist René Magritte, such as his Five-part painting 1931 or his surrealist postcard The key to the riddle (La solution du rébus) 1937. Magritte’s interrogation of objects, images and ideas greatly influenced Johns, who encountered his work as early as March 1954. In Four panels from Untitled 1972 1973–74 Johns recreates each panel as an embossing on the panel to its right (or, in the case of the last panel, as an embossing on the first), suggesting that we may understand each panel as related to the panel that precedes it. Johns would reinforce this relationship, remarking that ‘the cross-hatchings could be equated with the flagstones … the size of the body fragments is related to the size of the flagstones as well as echoing their placement on canvas’.12 The scholar Fred Orton see this work as an exploration of ‘metonymic relationships’.13 Metonyms are an expression where one thing is substituted for another. Unlike a metaphor, where the relationship between the signifier and the signified is often widely understood in a culture, the metonym ‘affords a kind of privacy to language’14 by obscuring the relationship between what is depicted and what it refers to. A metonymic chain of signification allows us to make associations between all four panels; however, Johns’s intentions remain undiscoverable. When it was put to him that this work seemed very private and personal, he simply remarked: ‘I certainly agree with you’.15 What we may discern is that the language of print is how this metonymic relationship is conveyed. By embossing each panel with the shape of the last, Johns also introduces a kind of intimacy, as he explores printmaking’s touch and the transference of images and tactile shapes transfer from the matrix to the paper.

Reproduction, summation and readymade: the influence of Marcel Duchamp

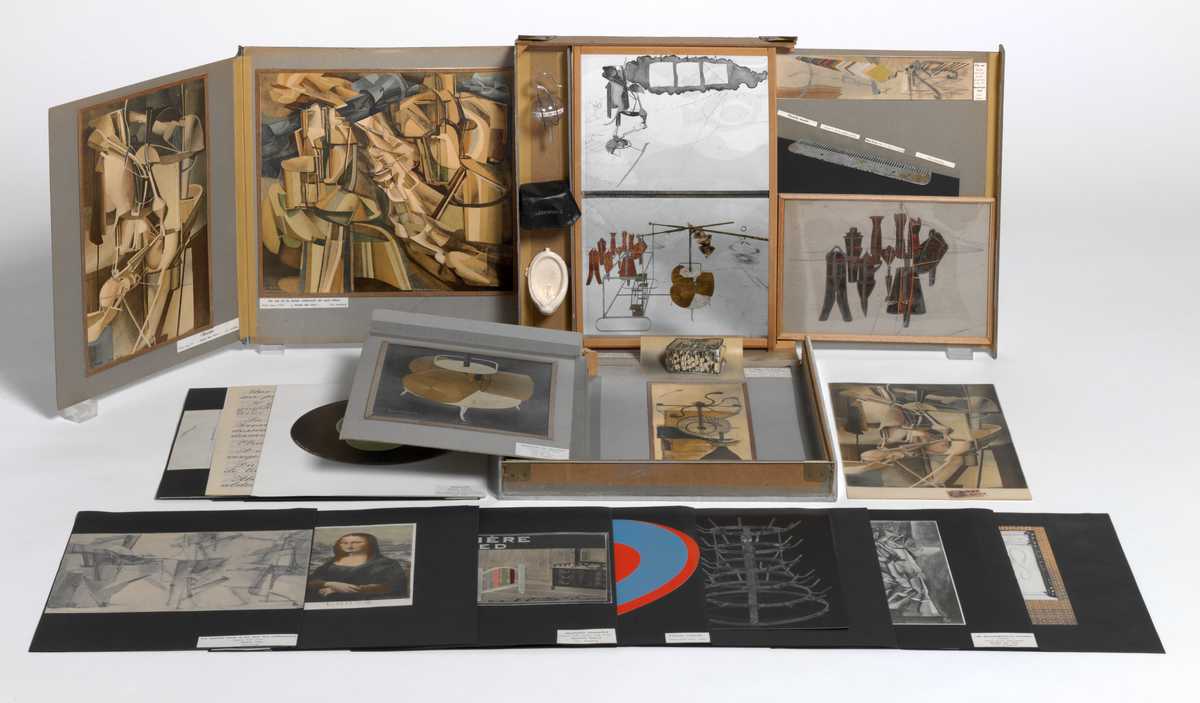

Marcel Duchamp, Box in a valise (Boîte en valise) 1942–54, cardboard and wooden box containing replicas and reproductions of works by Duchamp, 40.5 × 37.2 × 8.6 cm (closed), National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1979. © Marcel Duchamp. ADAGP/Copyright Agency, 2022

Both Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns admired, studied and owned the work of the iconoclastic French artist Marcel Duchamp. Duchamp was known for his rejection of ‘retinal’ art (art that serves the eye) and formulation of conceptual art (art that serves the mind). His ideas, such as the ‘readymade’ work of art, where a commonplace object would be deemed an artwork, were polarising for both artists and critics. Duchamp would also work with unconventional materials and use both chance procedures and precise technical drawing as a reaction to the self-expressive modes preferred by artists of his time. In the history of modern art, Duchamp was revolutionary, yet for an extended period of his life, he was also entirely indifferent towards his contributions, and ceased practising his art to play chess from 1923 onwards. As scholar Jonathan Katz notes, this ‘indifferent’ persona became ‘revelatory to [the] Cold War generation of queer artists’,16 for whom the homophobia of the fifties meant self-expression came with consequences. Duchamp’s artistic strategies greatly influenced the work of Rauschenberg and Johns.17 As Johns has reflected, ‘his ideas, his creations, triggered an intense curiosity in me’ and ‘boosted my confidence in my own [work]. I think he showed that an artist could have ideas other than the ones usually being discussed.’18

Joseph Cornell, Untitled (for Stephanie) c 1945, painted wood, collage, mirror, music box mechanism, 48.9 x 36.2 cm, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1973 © Joseph Cornell / Copyright Agency, 2022

In 1936 Duchamp began to conceive of a project that questioned printmaking’s characterisation as merely reproductive. This project was the Boîte-en-valise, a small portable ‘museum’ that summarised his many artistic achievements, contained in a compact box in a briefcase. The work was to be editioned, across the course of many decades, to 300 copies completed in 1971 after Duchamp’s death. Instrumental to the Boîte-en-valise’s construction was artist Joseph Cornell, who assisted Duchamp from 1942 to 1946. The Boîte-en-valise served as more than just a collection of miniature reproductions of Duchamp’s work; it was a means of questioning the perceived difference in value between a singular work of art and reproductions. Instead of mechanically reproducing his works, Duchamp pursued a ‘more interpretive reproduction’,19 using time-consuming and seldom-used printmaking methods such as collotype (an early photolithographic method) and pochoir stencils to reproduce his paintings and colour them by hand. As scholar Ecke Bonk notes, by shying away from the fast reproduction technologies available to him, Duchamp ‘blurred the boundaries between the unique art object and the multiple, between the original and its mechanical reproducibility’.20 Duchamp thought that it was ‘more fun to make a grouping that is expressive of one’s life’21 than to pursue novel work. Similarly, he thought the use of the term ‘reproduction’ to describe the Boîte-en-valise was ‘an error … [as] it can’t be an exact reproduction’.22

Jasper Johns, Bent “U”1971, from Fragments–according to what, color lithograph, 64 x 51.4 cm, published by Gemini Graphic Editions Limited, Los Angeles. National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1973. © Jasper Johns / Copyright Agency 2022

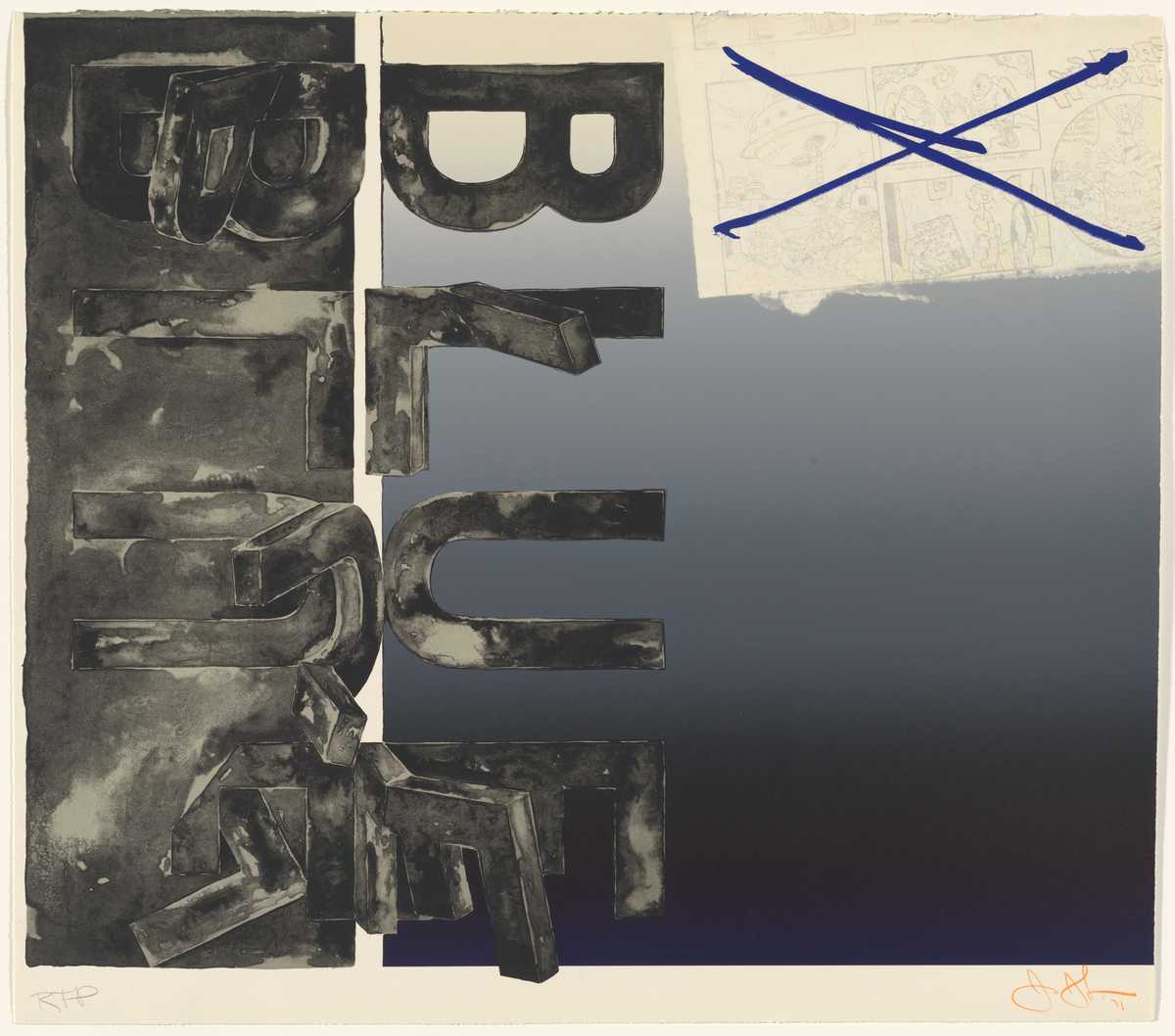

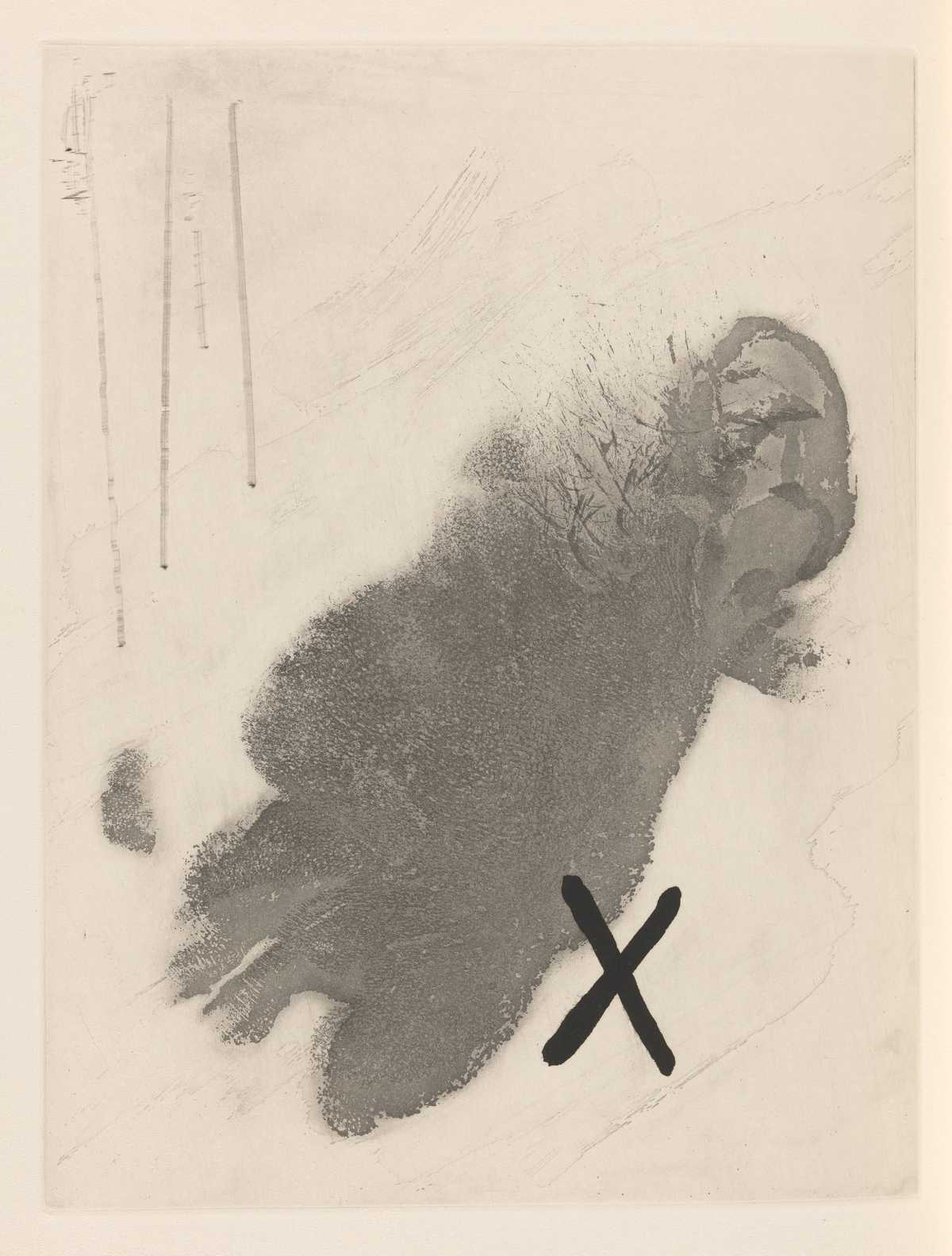

Jasper Johns, Bent “Blue” 1971, from Fragments–according to what series, colour lithograph with newspaper monotype, 64.6 x 73.4 cm, published by Gemini Graphic Editions Limited, Los Angeles. National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1973. © Jasper Johns / Copyright Agency, 2022

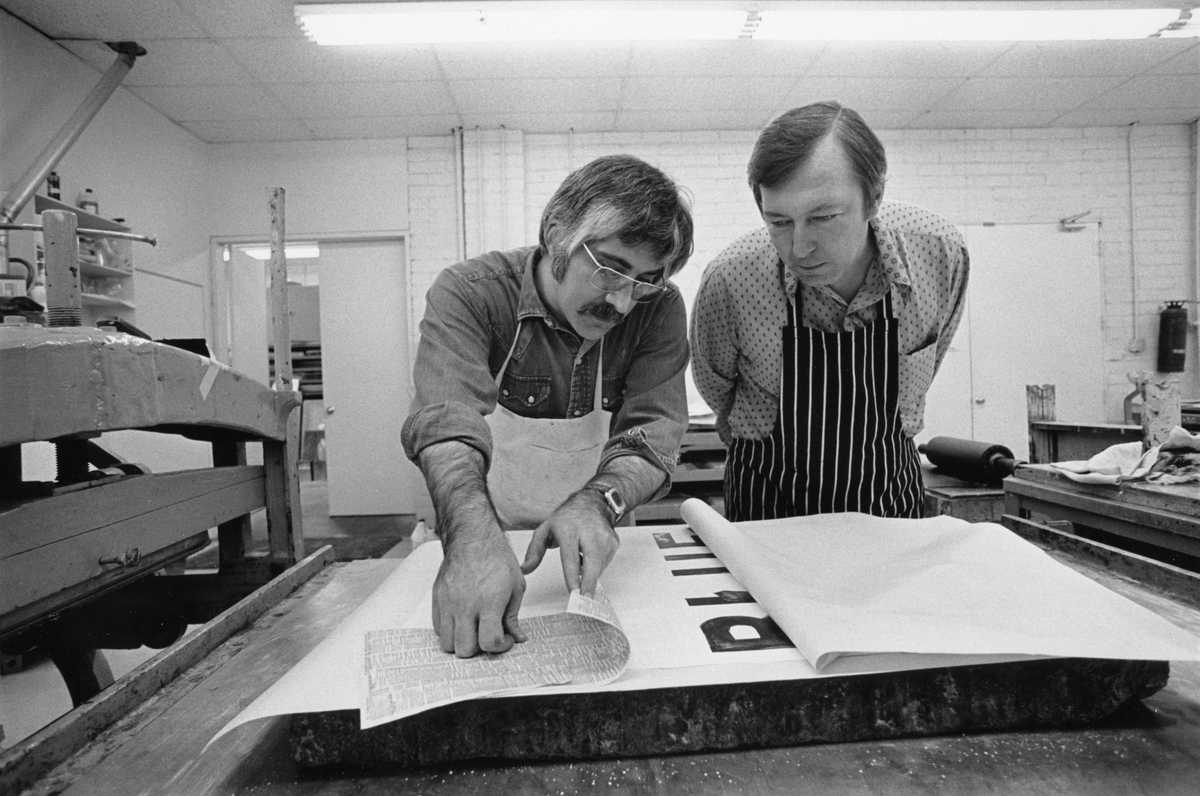

Jasper Johns instructing Kenneth Tyler regarding the positioning of the newspaper monotype on the inked stone for Bent "Blue" from Fragments—according to what series, Gemini GEL, Los Angeles 1971. Kenneth E Tyler Collection archive, NGA Study Collection © photographer, Malcolm Lubliner

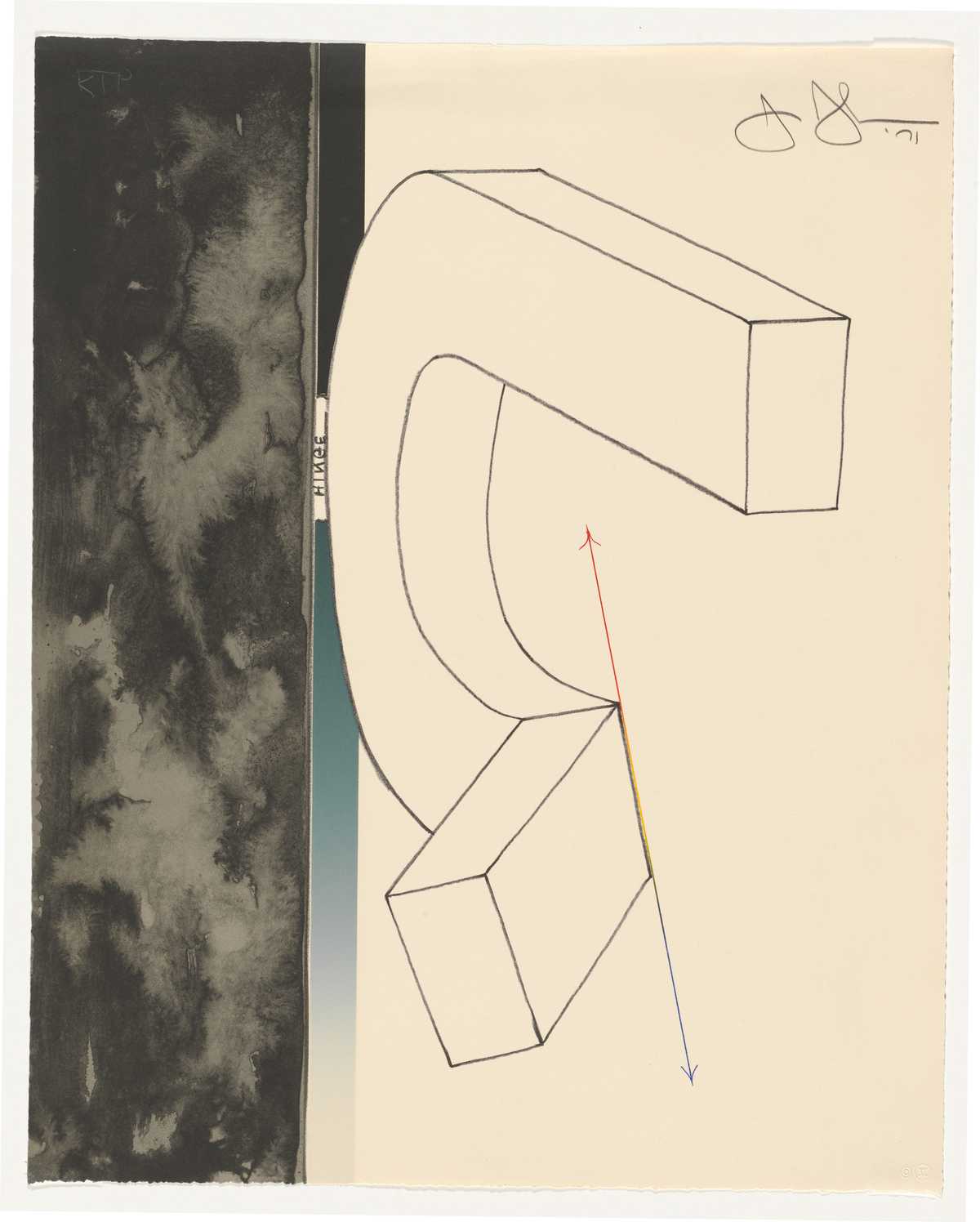

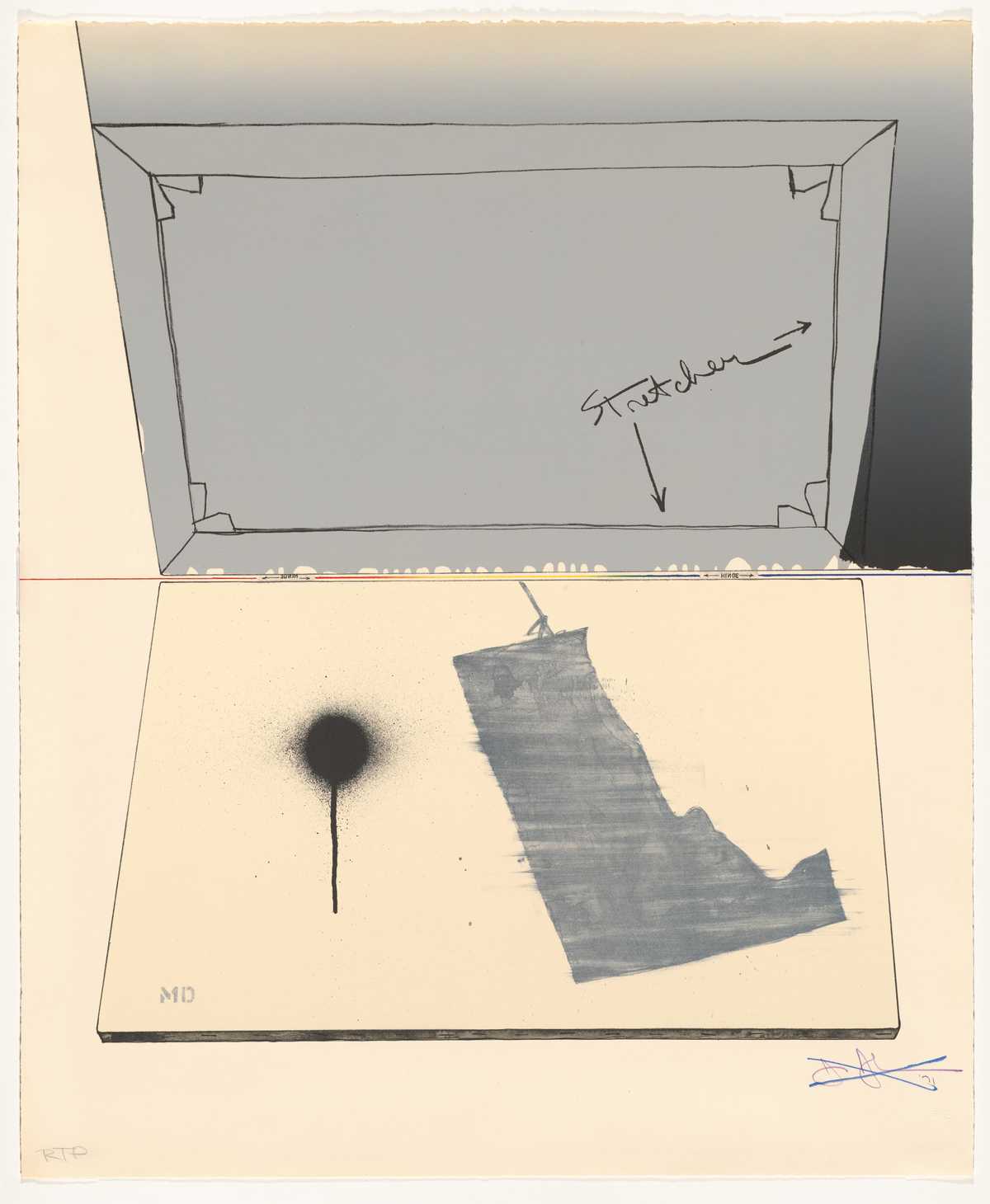

Jasper Johns, Hinged canvas 1971, from Fragments—according to what series, colour lithograph, 91.8 x 75.6 cm, published by Gemini Graphic Editions Limited, Los Angeles. National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1973 © Jasper Johns / Copyright Agency, 2022

Johns would pay homage to Duchamp’s restatement and reproduction of his work in 1971 with his Gemini GEL lithograph series Fragments—according to what 1971. Made with Tyler, this series of lithographs is based on Johns’s 1964 painting According to what, which, like Duchamp’s Boîte-en-valise, summarised the artistic themes and motifs from his career. In restaging this painting as a series of prints, Johns saw an opportunity to take what was in the painting ‘out of that space again … [and show] a thought that at one time didn’t just exist in the painting, but separately’.23 To make this series more than just a reproduction of his painting, he introduced deviations to the work’s original form and rescaled what were previously small details into larger works, such as the print Bent “U” 1971. In many works from the series, simple print techniques, including hinges and stencils associated with the pochoir technique used by Duchamp are depicted. In the lithograph Bent “Blue” 1971, three-dimensional letters of the word ‘blue’ appear to swing back and forth, leaving an impression of the word on both sides of a dividing line, as though they were print matrices or stamps. In the upper right corner, a unique monotype transfer of a newspaper has been struck through with a large ‘X’, another familiar process in printmaking where a printing matrix is defaced to ‘cancel’ the work and prevent further reproduction. This is also applied to his own signature in Hinged canvas 1971, as though it were a denial of authorship or act of self-erasure. In this print, Johns depicts a corner of his painting, part of which incorporates the projected shadow of Marcel Duchamp’s Self-portrait in profile 1957. Johns recalled that for the painting he ‘took a tracing of [Duchamp’s] profile, hung it by a string and cast its shadow so it became distorted’.24 By reproducing this distorted profile in the print, Johns again places himself in a lineage with the senior artist while also provoking questions regarding authorship and what we may consider to be an original, an indexical trace, or a reproduction.

Robert Rauschenberg, Publicon–station IV, 1978, published by Gemini Graphic Editions Limited, Los Angeles, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1979 © Robert Rauschenberg/Copyright Agency, 2023

The influence of Duchamp may also be seen in Rauschenberg’s 1978 assemblages from his Publicon series. These are intended to be opened and closed to reveal odd configurations of everyday materials, and are based on Renaissance altarpieces or the Stations of the Cross. In his youth, Rauschenberg had planned to become a preacher, but confronted with the restrictive morality of the Church of Christ, left at the age of fifteen.25 Reflecting this experience, curator Ruth Fine has said that the Publicon series address the ‘matter of spirituality—or lack of it—in contemporary culture’.26 The inclusion of a wheel in Publicon–station IV 1978 references Duchamp’s Bicycle wheel 1913, along with the folding, sliding structure that resembles his Boîte-en-valise. The investigation of contemporary attitudes to spirituality is common to both works: the idea of the auratic, singular artwork is called into question through reproduction and the readymade or, as Marcel Duchamp would say: ‘Art has absolutely no existence as veracity, as truth. People always speak of it with this great religious reverence, but why should it be so revered?.’27

Imprinted, mirrored and receptive: surfaces

The work of Rauschenberg and Johns does not resemble how we see the world as we move through it. A landscape painting, or perhaps a portrait, resembles what we may see when we stand looking out at the world, or at another person. But the work of Rauschenberg and Johns more accurately resembles what we see when looking down at a table or surface where objects are scattered. Their surfaces are horizontal, a quality art critic Joseph Steinberg noticed in their work and shared in his 1968 lecture ‘Other criteria’.28 He saw this as a radical reorientation of a picture’s logic and called it the ‘flatbed picture plane’. Significantly, Steinberg borrowed this term from the flatbed presses used for printmaking and would compare such work to printer’s proofs and cancelled plates: ‘any receptor surface on which objects are scattered, on which data is entered, on which information may be received, printed, impressed’.29

Jasper Johns (artist), Samuel Beckett (author), Face 1976, from Foirades/Fizzles, etching, bound artist book, 27.4 x 21 cm (image), published Petersburg Press, printed by Atelier Crommelynck, Paris. National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1976.

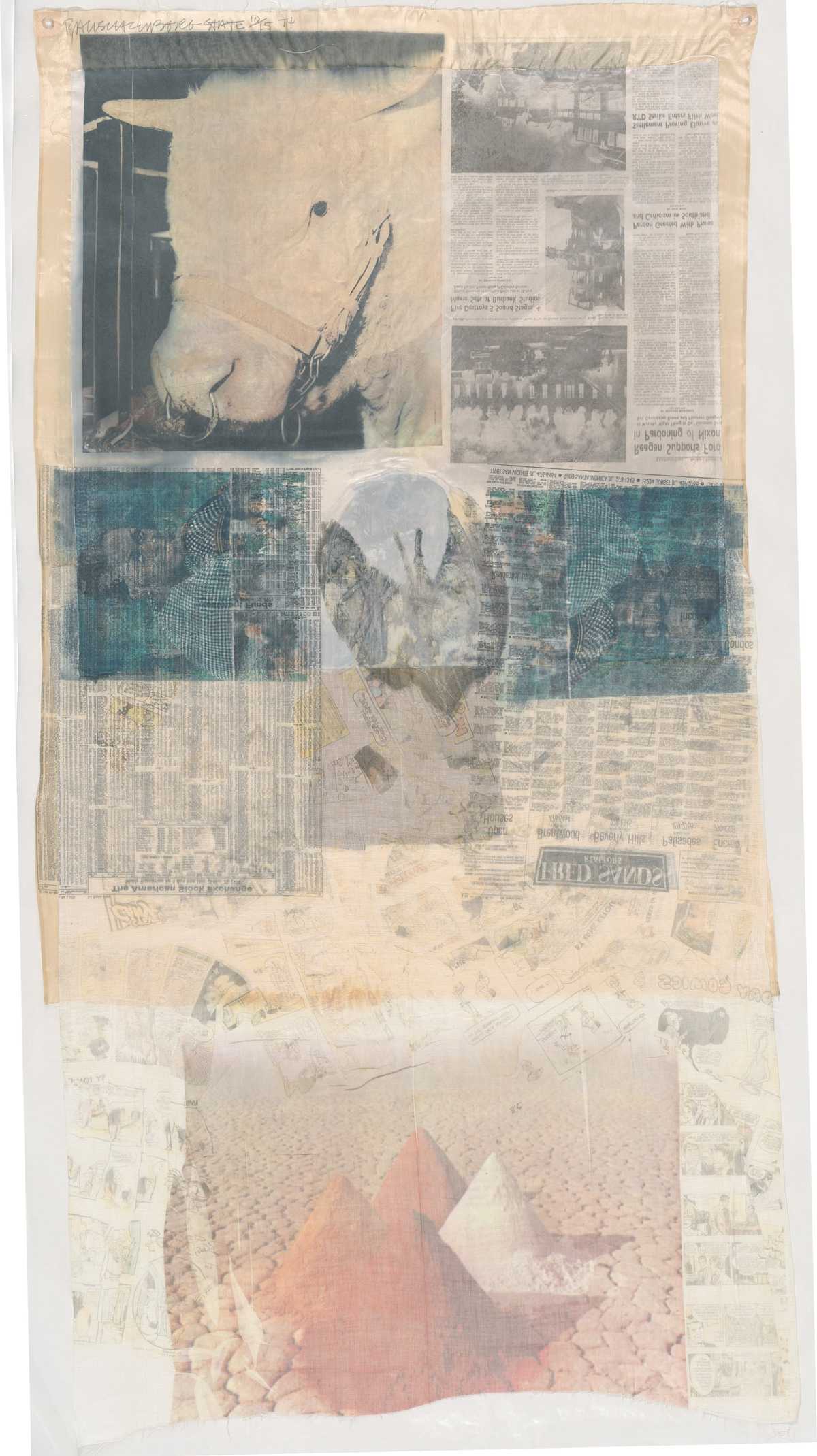

Robert Rauschenberg, Ringer (State) 1974, from Hoarfrost series, offset lithography and newspaper transferred to collage of fabric and paper bags, 177.8 x 91.4 cm, published by Gemini Graphic Editions Limited, Los Angeles. National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1976. © Robert Rauschenberg / Copyright Agency, 2022

Robert Rauschenberg, Pull 1974, from Hoarfrost series, offset lithograph and newspaper transferred to collage of fabrics and paperbags, 215.9 x 121.9 cm, published by Gemini Graphic Editions Limited, Los Angeles. National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra,purchased 1976 © Robert Rauschenberg / Copyright Agency, 2022

This idea of the flatbed picture plane draws our attention to Johns’s and Rauschenberg’s intuitive replication of the logic of printmaking: images are created through impressions from the horizontal contact between a print matrix and a support. Steinberg would describe Johns’s artworks as ‘surface[s] observed during impregnation, observed as it receives a message or imprint from real space’.30 This can be seen in Johns’s use of his own body as a stamp in Face, in the artist book Foirades/Fizzles he created with poet Samuel Beckett in 1976. This image was originally created by Johns covering his face in mineral oil, and then pressing his oiled face onto paper. The paper surface was then dusted with pigment that adhered to the oil, revealing the moment of contact between the artist and the sheet of paper for us to observe. Similarly, Rauschenberg would create works using solvent transfers, whereby pressing down on magazine images he could transfer them onto a new surface. Steinberg marvelled at Rauschenberg’s ‘imaginative confrontation[s] … produced by pressing down on a desk’.31 This technique was developed in the spring of 1958, while Rauschenberg and Johns were in Cuba. By dousing a newsprint image in lighter fluid, Rauschenberg discovered he could transfer a pale mirrored version of the original to paper through rubbing the back of the newsprint with an empty ball-point pen. A variation on this technique would serve one of Rauschenberg’s most radical print series, Hoarfrost editions 1974. In his studio, Rauschenberg had noticed that while cleaning a lithography stone with solvent, the image drawn onto the matrix would transfer back into the folds of the cloth he used to wipe the stone, just as his solvent transfer drawings had reproduced their form by being pressed upon over a decade earlier. Inspired by the soft blur of the images through layers of cloth, he took the idea to create editions at Gemini GEL. With works such as Scrape, Pull and Ringer 1974, the Hoarfrost editions discarded the traditional print matrix, such as a lithography stone or etching plate, and instead used thickly layered newspapers, magazine pages, and offset lithographs as the source of the impression. By creating a thick bed of such material and then spraying this with solvents, Rauschenberg softened the inks so that when he put the magazine papers through a lithography press, the images transferred onto a silk fabric surface. Rauschenberg commented that the delicately blurred images that resulted ‘were almost like brushstrokes’,32 despite them being achieved using printmaking processes.

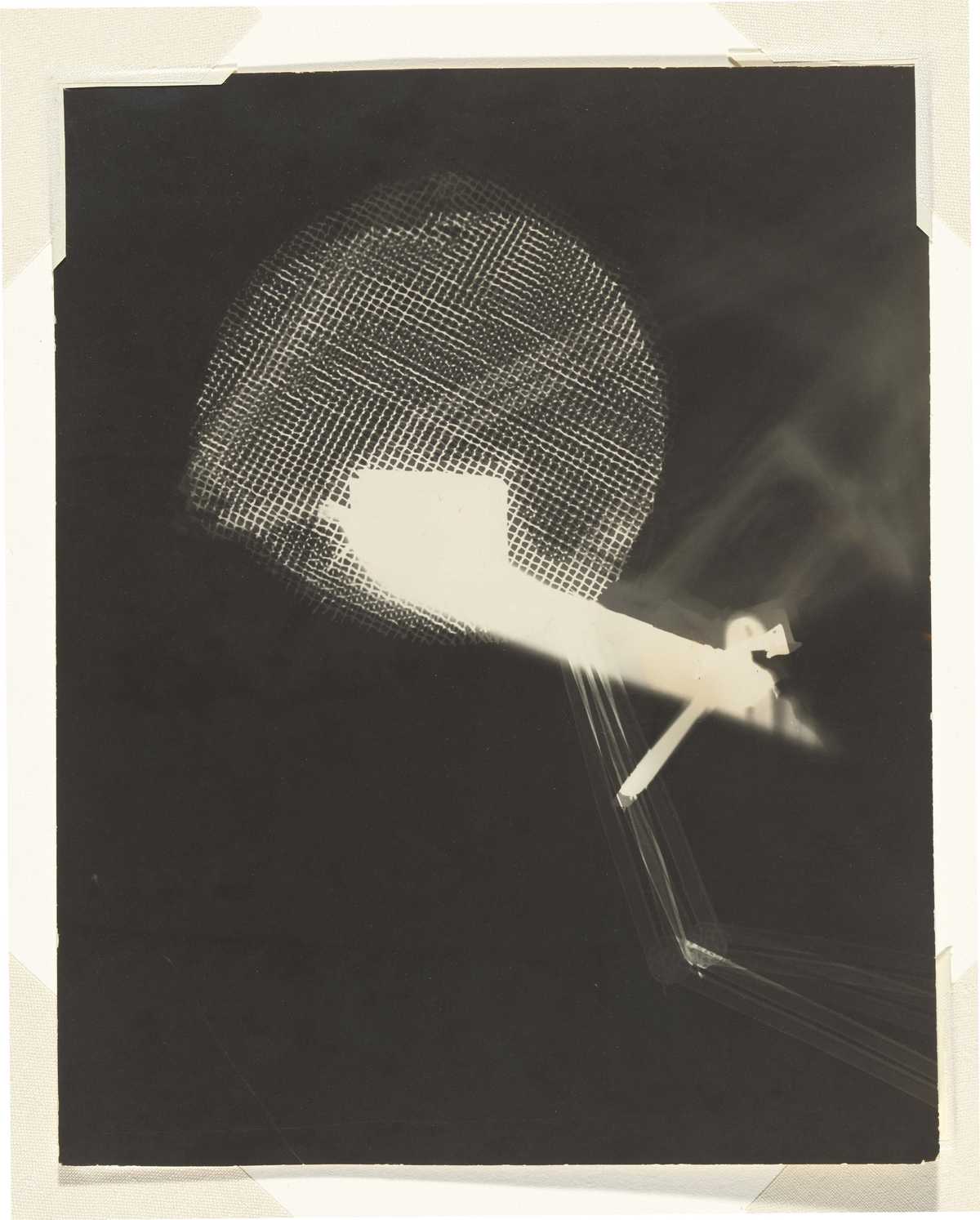

László Moholy-Nagy, Photogram (pipe and glass), c 1926, gelatin silver photograph, 21.7 x 17.2 cm, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1984

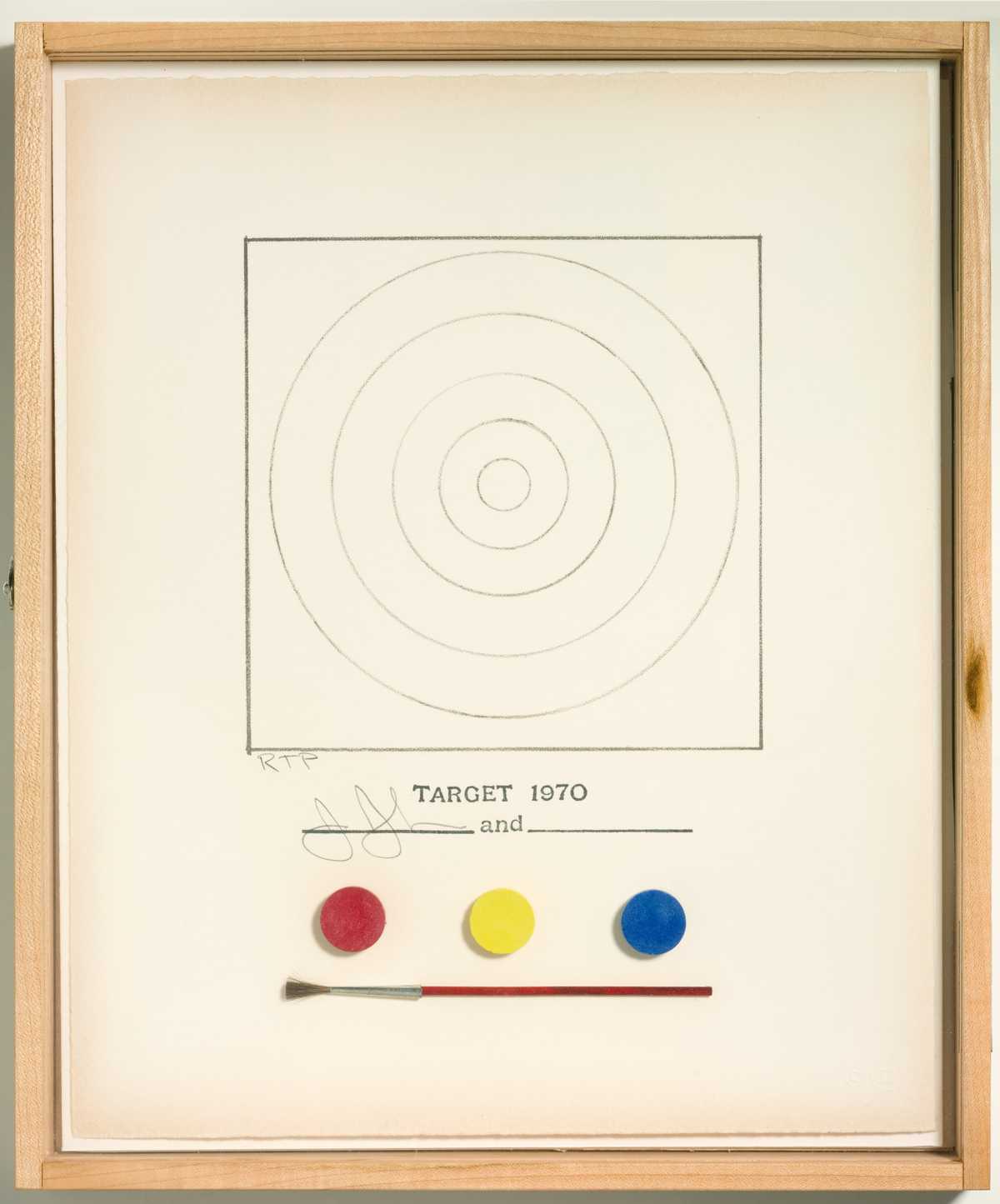

Jasper Johns, Gemini G.E.L., Target, 1971, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, Purchased 1973. © Jasper Johns. VAGA/Copyright Agency.

Steinberg was to conclude that the flatbed picture plane was the invention of a pictorial surface that ‘let the world in again’.33 The scholar Branden Joseph traces a similar idea to the influence of Hungarian painter and photographer Laszlo Moholy-Nagy. In his 1938 book The new vision Moholy-Nagy saw modern painting progressing to a ‘final simplification’ as ‘an ideal plane for kinetic light and shadow effects which, originating in the surroundings, would fall upon it’.34 This idea resembled Moholy-Nagy’s own work, such as his Photogram (pipe and glass) c 1926, created by placing objects on a photosensitive surface and exposing this to light. Rauschenberg and Johns would use a similar technique using photosensitive blueprint paper for their commercial work dressing department store windows under the pseudonym Matson Jones in the 1950s. According to Joseph, the composer John Cage drew a parallel between Moholy-Nagy’s ideas and the work of Rauschenberg. This then influenced the course of Rauschenberg’s and Johns’s work, as both began to investigate methods that would decentre the authorial voice of the artist and allow the viewer and surrounding environment to become a part of the work itself. This became a strategy for navigating the homophobia of the 1950s. Rauschenberg would use ‘less specific’ images in odd combinations ‘so that there is room for everyone’s imagination’,35 while Johns would make clear that he was interested only in ‘looking at things, not in deciding … what they ought to be’.36 Extending these ideas, both Johns and Rauschenberg would invite the viewer to become a part of the picture. Johns’s Target 1970 demonstrates this idea by inviting the audience to partake in the colouring of one of his iconic target motifs, by setting watercolour pigment pots below the work and leaving room for the viewer to sign the work alongside Johns’s signature.

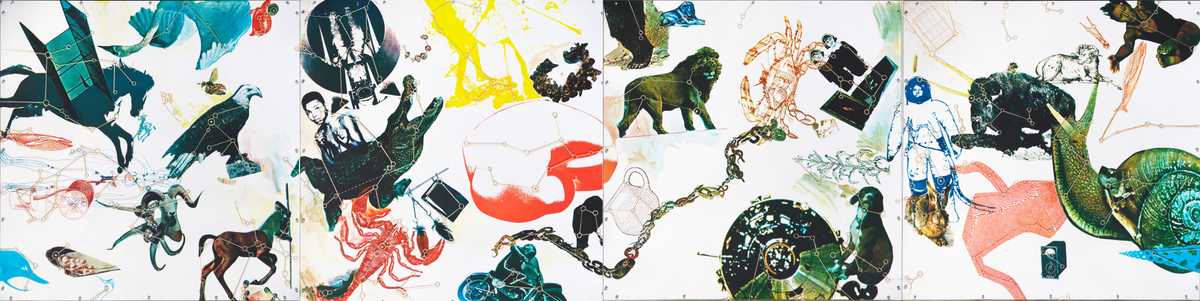

Rauschenberg would make environmentally responsive works using mirrored surfaces, including Star quarters, a four-panelled screenprint made in 1971. It depicts fictional figures that form constellations in the night sky, on a mirrored Perspex surface in which we can simultaneously view ourselves and our surroundings, fulfilling Rauschenberg’s desire in his practice ‘that the room would become a part of the [artwork]’37 and explore his idea of ‘the extremely dangerous possibility that you might be art’.38

Robert Rauschenberg, Multiples Inc., Castelli Graphics, Styria Studios, Star quarters, 1971, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, Purchased 1980. © Robert Rauschenberg. VAGA/Copyright Agency.

Breaking the mould: materials

Integral to the work of both Rauschenberg and Johns during their time working at Gemini GEL was the experimentation led by Tyler into new materials that could alter the boundaries of traditional printmaking. Tyler began his career concerned that the materials available for lithography were inadequate and those available were difficult to source. During his training at Tamarind Lithography, Tyler was closely involved in the investigation of European printing papers to test their suitability for printing from lithography stones.39 The strength, stretch and receptivity of these paper surfaces came under question and would lead to Tyler’s extensive journey to revive handmade papermaking for artists in the United States. During the early years of these investigations, Rauschenberg and Johns would play an instrumental role in experimenting with printing surfaces, and the material conditions would inform their work’s development.

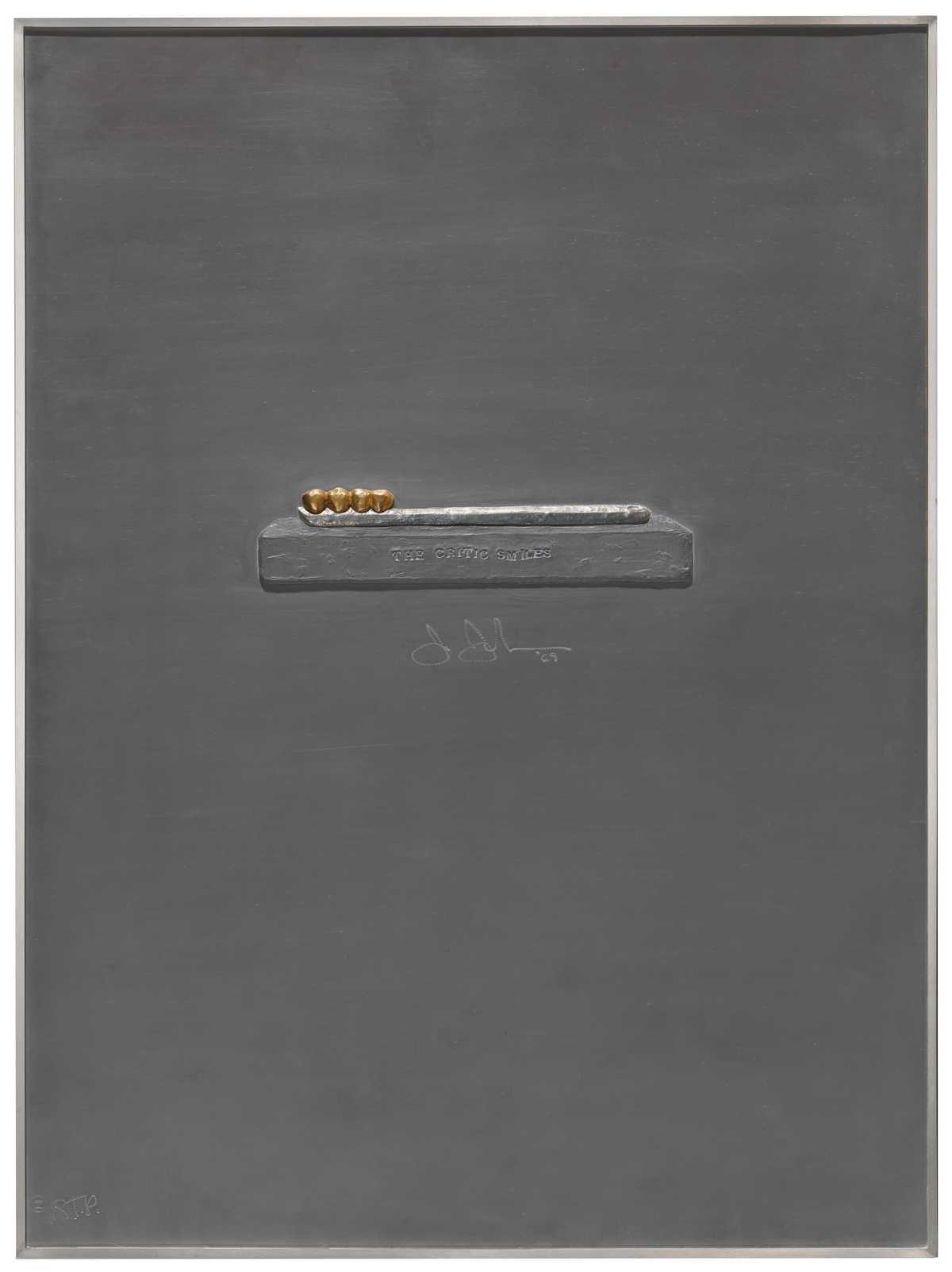

Jasper Johns, The critic smiles 1969, from Lead reliefs series, sheet lead relief, tin relief, gold casting, 58.6 x 43.2 cm, published by Gemini Graphic Editions Limited, Los Angeles. National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1973. © Jasper Johns / Copyright Agency, 2022

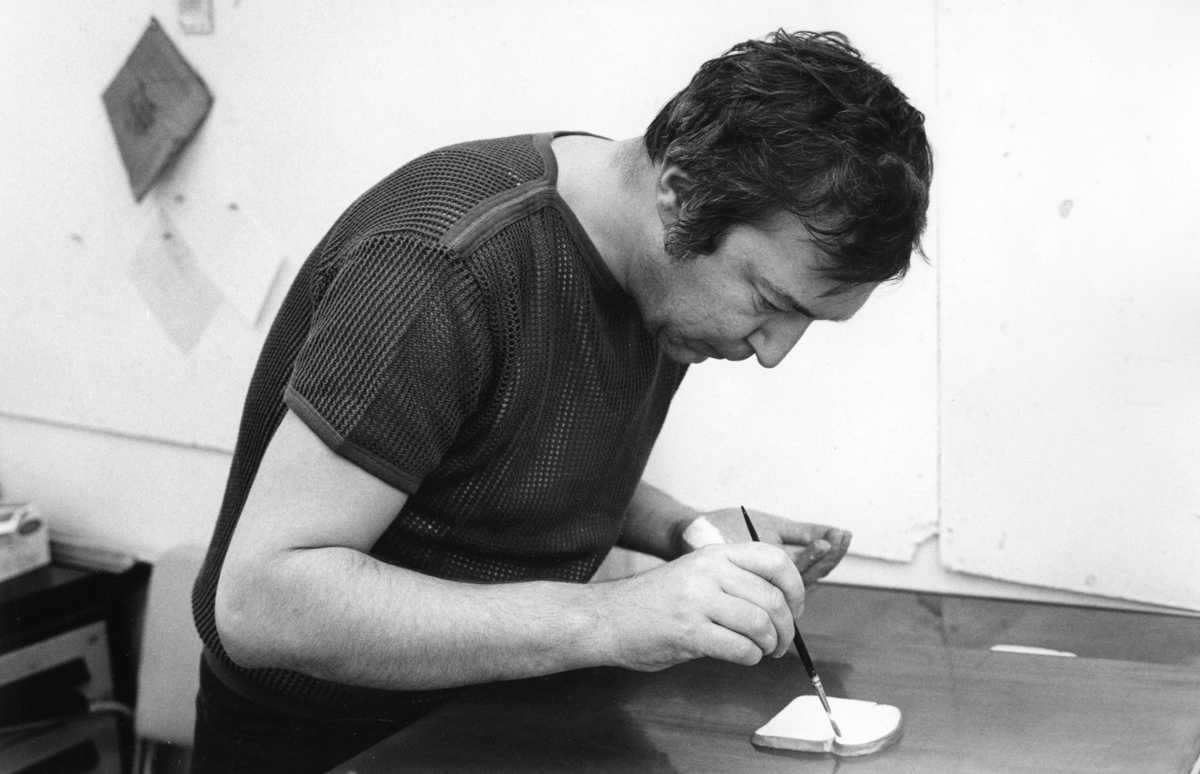

Jasper Johns hand-painting Bread from the Lead reliefs series, Gemini GEL, Los Angeles, 1969, Kenneth E Tyler Collection archive, NGA Study Collection © photographer, William Richard Crutchfield

Johns’s 1968 Lead reliefs series was originally intended to be made from embossed paper, but this material tore as the complex three-dimensionality of the prints pushed the strength of the commercial paper available at the time.40 Tyler and Johns decided to experiment instead with thin sheets of soft lead as a substitute. This medium, as a substrate for ‘printing’ in the form of embossing, suited Johns’s preference for neutral grey tones in his work and was familiar to the artist who had recently acquired a work made of lead by the artist Richard Serra.41 Wax models were created for nearly every work in the Lead reliefs series and these were then converted to plaster casts that would be used to emboss a sculptural relief onto lead sheets using 700 tons of pressure from an industrial forming machine. This series blurred the line between traditional printing and industrial metalwork,42 while allowing Johns to create odd juxtapositions between materials—he incorporated gold into The critic smiles 1969 and paper with oil paint into the edition of Bread 1969.

Robert Rauschenberg, Link 1974, from Pages and fuses series, pressed paper pulp with screenprinted tissue embedded, 60 x 49 cm(irregular), published by Gemini Graphic Editions Limited, Los Angeles. National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased1975. © Robert Rauschenberg / Copyright Agency, 2022

Robert Rauschenberg laying screenprinted tissue paper onto newly formed wet colour pulp for Link from the Pages and fuses series, Richard de Bas Paper Mill, Ambert, France, 1973, Kenneth E Tyler Collection archive, NGA Study Collection © photographer, Gianfranco Gorgoni

This experience informed Tyler’s growing desire to master the art of papermaking to allow artists a greater range of control and experimentation in their prints. He began to seek out traditional methods for creating handmade papers in Europe through his connections with the French paper company Arjomari-Prioux and conceived of a project to create experimental papers with an artist. Robert Rauschenberg’s love of collaboration and willingness to respond to material processes made him an ideal candidate to accompany Tyler. In 1973, they set out with paper experts Elie d’Humieres and Vera Freeman for the medieval Richard de Bas papermill on the outskirts of the village of Ambert, France. This mill, operational since the sixteenth century, had gigantic stone rag beaters that were powered by water from a nearby stream and ancient screw presses that had to be turned by several people using a large log. Rauschenberg spent four days working to create what would be named the Pages and fuses series. Arts writer Joseph E Young called this series ‘the first works of art in the history of papermaking that represent a major artist’s personal involvement in transforming the art of making paper into art itself’.43 These works, composed of irregular, thick, sculptural paper dyed vivid hues and couched with silkscreened tissue papers take what is usually the substrate of printmaking and turn it into sculptural form, intended to be displayed upright and seen from the front and back.

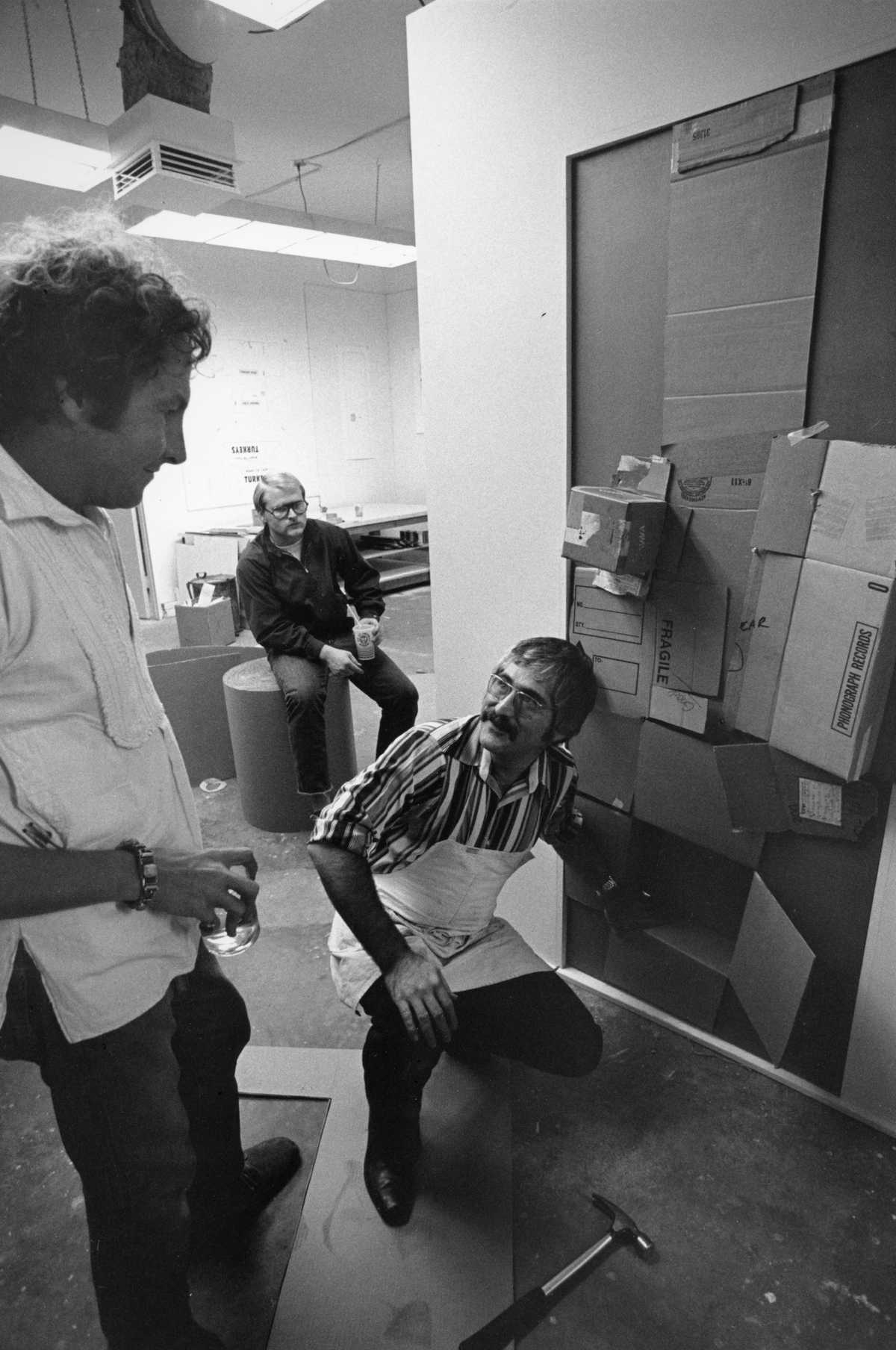

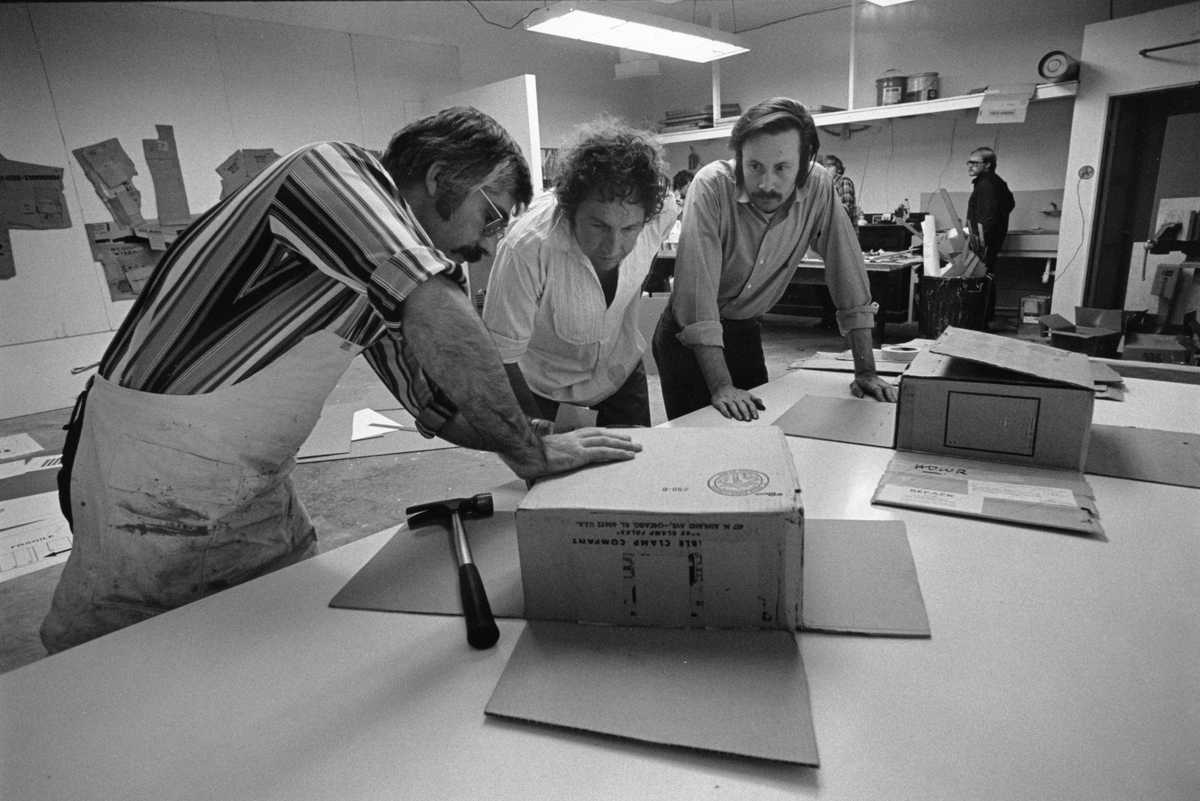

Rauschenberg had been investigating the artistic qualities of a different, more commonplace type of paper—cardboard— since 1970. Having moved from New York to Captiva Island, Florida, Rauschenberg had to contend with the change in materials available to him. Having previously combed the streets of New York for objects to use in his work, revelling in the abundance of refuse that could be found in the city, he found that the pristine wilderness of Captiva suggested different materials and precipitated ‘a desire … to work in a material of waste and softness. Something yielding’.44 The material he chose was cardboard, reflecting Rauschenberg’s conviction that ‘there’s no such thing as “better” material’45 with which an artist can make art. Having exhibited a series of genuine cardboard works at Castelli Gallery in 1970, Rauschenberg decided to take this idea one step further by creating an edition of prints that appeared to be made from cheap abundant cardboard but were actually elaborate recreations of cardboard boxes made using lithography, screenprinting, and stamps to faithfully recreate the worn, dishevelled boxes on which they were based. The largest work in the series, Cardbird door 1971, is designed to fit a standard door frame, and one of the edition is used by Jasper Johns as the entrance door to his dining room in New York.

Both Rauschenberg and Johns were highly engaged with the processes and materials of printmaking. They saw this ‘different physique’ as an opportunity to explore new ideas derived from new methods for creating work. These methods spoke directly to the abundance of printed matter in twentieth-century life, and how printmaking methods shaped everyday culture. Their understanding of the physical processes of making prints created rich new avenues to convey ideas. As Rauschenberg would put it in 1991: ‘I use [printmaking] as a kind of refresher. I’ve consistently been impatient, restless, and curious, and I’ve satisfied this weakness by changing mediums often … There must be thousands of other things that I haven’t thought of, or haven’t occurred to anybody, that need to be done’.46

Robert Rauschenberg, Robert Dressen and Kenneth Tyler during the production of Cardbird door from the Cardbird series at GeminiGEL, Los Angeles, 1971, photographer: Malcolm Lubliner. Kenneth E Tyler Collection archive, NGA Study Collection © photographer, Malcolm Lubliner

Kenneth Tyler, Robert Rauschenberg and Jeff Wasserman examining screenprinting on Cardbird door from the Cardbird series in themultiple studio, Gemini GEL, Los Angeles, 1971, photographer: Malcolm Lubliner. Kenneth E Tyler Collection archive, NGA Study Collection © photographer, Malcolm Lubliner

Banner Image: Jasper Johns signing the edition of Target, Gemini GEL, Los Angeles, 1971. Kenneth E Tyler Collection archive, NGA Study Collection, photograph: Malcolm Lubliner.

Robert Rauschenberg, Cardbird door 1971, from Cardbird series, corrugated cardboard, Kraft paper, tape, wood, metal, photo offset and screen printing, 204 x 95 x 32.5 cm, published by Gemini Graphic Editions Limited, Los Angeles. National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1975. © Robert Rauschenberg / Copyright Agency, 2022

Header image: Jasper Johns signing the edition of Target, Gemini GEL, Los Angeles, 1971. Kenneth E Tyler Collection archive, NGA Study Collection © photographer, Malcolm Lubliner

Notes

- — See Pat Gilmour, Kenneth Tyler: master printer and the American print renaissance, Australian National Gallery, Canberra, 1986.

- — Gilmour, p 48.

- — David Vaughan, 'The fabric of friendship: Jasper Johns in conversation with David Vaughan' in Susan Sontag et al, Cage, Cunningham, Johns: dancers on a plane, Alfred A Knopf, New York, with Anthony d’Offay Gallery, London, 1990, pp 137–42. As reprinted in Kirk Varnedoe, Jasper Johns: writings, sketchbook notes, interviews, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1996, p 236.

- — Grace Glueck, ‘‘Once established, ideas can be discarded’’, New York Times, 16 October 1977, p 75.

- — Mark Rosenthal, Artists at Gemini G.E.L.: celebrating the 25th year, Harry N Abrams, New York, 1993, p 142.

- — Jennifer L Roberts, ‘Contact: art and the pull of print’, Part 1: pressure, The 70th A. W. Mellon Lecture in the Fine Arts: National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, 2021, viewed 12 October 2021, https://www.nga.gov/research/casva/meetings/mellon-lectures-in-the-fine-arts/roberts-2021.html.

- — Barbara Rose, Robert Rauschenberg: an interview with Barbara Rose, Elizabeth Avedon Editions, New York, 1987, p 86.

- — Gene R Swenson, ‘What is pop art? part II’, Artnews, vol 62, no 10, February 1964, p 43.

- — Roberta Bernstein, ‘Jasper Johns’s painting and sculpture, 1954 – 2014: redo an eye’ in Jasper Johns: catalogue Raisonné of painting and sculpture, The Wildenstein Plattner Institute, New York, 2016, p 48.

- — Bryan Robertson and Tim Marlow, ‘Jasper Johns’, Tate: The ArtMagazine (London) no 1, Winter 1993, p 46.

- — Joseph E Young, ‘Jasper Johns: an appraisal’ Art International, vol 13, no 7, September 1969, p 52.

- — Roberta JM Olson, ‘Jasper Johns: getting rid of ideas’, The SoHo Weekly News, vol 5, no 5, 3 November 1977, As reprinted in Varnedoe, Jasper Johns, p 168.

- — Fred Orton, Figuring Jasper Johns, Reaktion Books, London, 1994, p 45.

- — Orton, p 31.

- — Peter Fuller, ‘Jasper Johns interviewed’, Art Monthly (London), no 18, July/August 1978, p 8.

- — Jonathan Katz, ‘Identification’ in Difference/indifference: musings on postmodernism, Marcel Duchamp and John Cage, Routledge, London, 1998, p 54.

- — See Dorothy Kosinski, Dialogues: Duchamp, Cornell, Johns, Rauschenberg, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, TX, 2005.

- — Demosthène Davvetas, ‘Jasper Johns et sa famille d’objets’, Art Press (Paris), vol 80, April 1984, p 11–12. As reprinted in Varnedoe, Jasper Johns, p 217; Terry Winters, ‘Jasper Johns: In the studio. A conversation with Terry Winters’, in Jasper Johns: new sculpture and works on paper, Matthew Marks Gallery, New York, 2011, p 149.

- — Ecke Bonk, Marcel Duchamp: the portable museum: the making of the Boîte-en-valise, trans David Britt, Thames and Hudson, London, 1989, p. 148.

- — Bonk, p 20.

- — Marcel Duchamp, 1965, as quoted in Bonk, p 163.

- — Bonk, pp 184–85.

- — Francis Naumann, According to what and watchman, Gagosian Gallery, New York, 1992, p 19.

- — John Coplans, ‘Fragments according to Johns: an interview with Jasper Johns’, The Print Collector’s Newsletter, vol 3, no 2, May–June 1972, p 30.

- — Rose, p. 10.

- — Ruth Fine, quoted in Mary Lynn Kotz, Rauschenberg: art and life, Harry N Abrams, New York, 1980. p 218.

- — Marcel Duchamp, quoted in Calvin Tomkins, Off the wall: a portrait of Robert Rauschenberg, Picador, New York, 1980, p 116.

- — Steinberg’s essay ‘Other criteria’ addresses the work of Rauschenberg; however, in 1962 he first identified the shift to working on a horizontal picture-plane in relation to the work of Johns in ‘Jasper Johns: the first seven years of his art’. Both essays are published in Leo Steinberg, Other criteria: confrontations with twentieth-century art, Oxford University Press, New York, 1972.

- — Steinberg, ‘Other criteria’, p 84.

- — Steinberg, ‘Jasper Johns: the first seven years’, p 51.

- — Leo Steinberg, ‘Other criteria’, p 86–87.

- — Kotz, p 162.

- — Steinberg, ‘Other criteria’ p 90.

- — Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, The new vision, 1938 as reproduced in Branden W Joseph, Random order: Robert Rauschenberg and the neo-avant-garde, MIT Press, London, 2003, p 36.

- — Rose, p 77.

- — Selden Rodman, The insiders: rejection and rediscovery of man in the arts of our time, Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge, LA, 1960, p 36.

- — Rose, p 56.

- — Barbara Rose, Robert Rauschenberg: an interview with Barbara Rose, Elizabeth Avedon Editions, New York, 1987, p 111.

- — Amy Hughes, ‘Wild and immaculate: Kenneth Tyler’s early use of handmade paper at Gemini GEL’, Hand papermaking, vol 34, no 1, 2019, p 4.

- — Jane Kinsman, Lichtenstein to Warhol: the Kenneth Tyler Collection, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 2019, p 32.

- — Kenneth Tyler, email to the author, 7 March 2021.

- — The details of this project are outlined in the ‘Final progress report, Gemini grant’ submitted to the National Foundation on the Arts and Humanities in September 1968. See National Gallery of Australia, Kenneth Tyler Collection archive papers B67.90–97.

- — Kotz, p 193.

- — Kotz, p 185.

- — Rose, p 58.

- — Rosenthal, p 150.