Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns are considered two of the most significant artists of the twentieth century, whose work changed the course of American art. Their shared aesthetic sensibility is a result of the creative dialogue they held while they were young artists in a relationship. This dialogue moved against the grain of the dominant art movement of the time, Abstract Expressionism, and for many years took place in private. Instead of seeking public validation during the homophobic culture of the 1950s they gave each other permission to make art as they wanted to,1 which became the crucible for both their lifelong practices. Their work questioned ideas of authorship, value, and how art needed to communicate to a public audience. This was the result of each of them being the audience for the other.

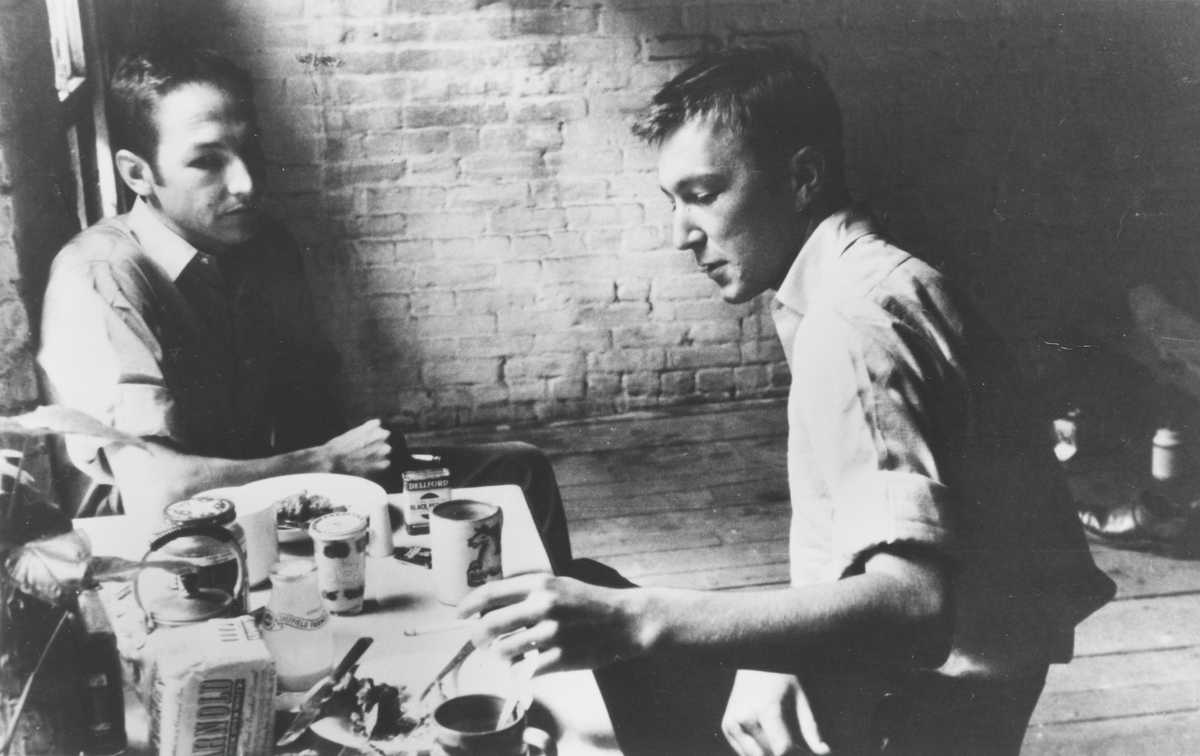

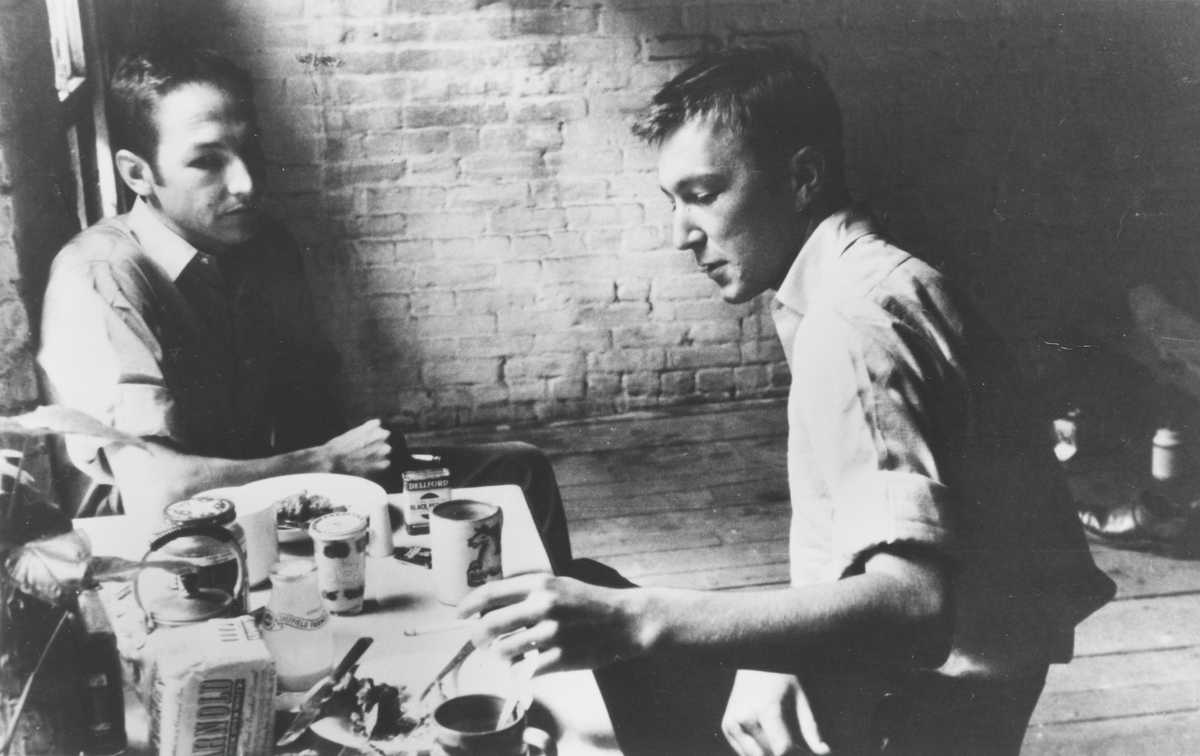

Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns in Johns’s Pearl Street studio, New York, NY, United States, 1954, gelatin silver print, 20.3 x 25.4 cm. Image courtesy Robert Rauschenberg Foundation © photographer, Rachel Rosenthal

Public art, private lives

Rauschenberg and Johns lived and worked in adjacent studios in New York City during their relationship from 1953 to 1961. Being in a same-sex relationship when it was illegal in the United States meant they had to navigate a homophobic society that prohibited the public expression of their sexuality. At the time, New York’s artistic culture was focused on Abstract Expressionism, an art movement often framed as heroic and an exposure of the self and subconscious. Mindful of their personal circumstances, both Rauschenberg and Johns claimed their art was not about themselves and did not reflect their personalities. The conflict between an artwork’s visibility and their need for personal invisibility was inextricable from their dissociation of the artwork from the artist. Johns would describe this as ’making a picture, which somehow has a public life [but] not making a picture of oneself to have a public life. So, in presenting the picture, one is not presenting oneself’.2 To create such work, Johns and Rauschenberg deployed different methods: Johns would depict ‘things the mind already knows’,3 such as numerals, letters, targets, and flags; while Rauschenberg’s work was an accumulation of images and things from the world around him, the product of ‘random order’.4 To reinforce the impersonal nature of their work, they would continually assert that we, the audience, create our own meanings from it. This proposition was something that both artists would often pose to critics: ‘Meaning belongs to the people’,5 Rauschenberg would say, while Johns would tactfully relay that ‘the artist is not tied to the public use of his work … it’s best to cut oneself off from what happens after’.6 Their attempts to dissociate themselves from their work would lead writers, for instance art critic Moira Roth, to characterise their work as neutral, passive, or indifferent.7

While Rauschenberg and Johns would claim their work was not about themselves, there is also the possibility that it did have personal meaning, but one that was ‘encoded’8 within the work and known only to a small audience. This may have been known only to their queer community, their close friends, or, while they were in a relationship, to each other. As Jasper Johns has remarked, ‘for a number of years we were each other’s main audience’, working ‘on a daily basis to the exclusion of most other society’.9

The truth is likely somewhere between these two ideas: Rauschenberg and Johns produced art that had encoded personal meaning, while they both questioned how art communicated to other viewers who would bring their own perspectives. While their work is sometimes visually dissimilar, it shares this artistic philosophy, and its development can be traced to Rauschenberg’s formative years.

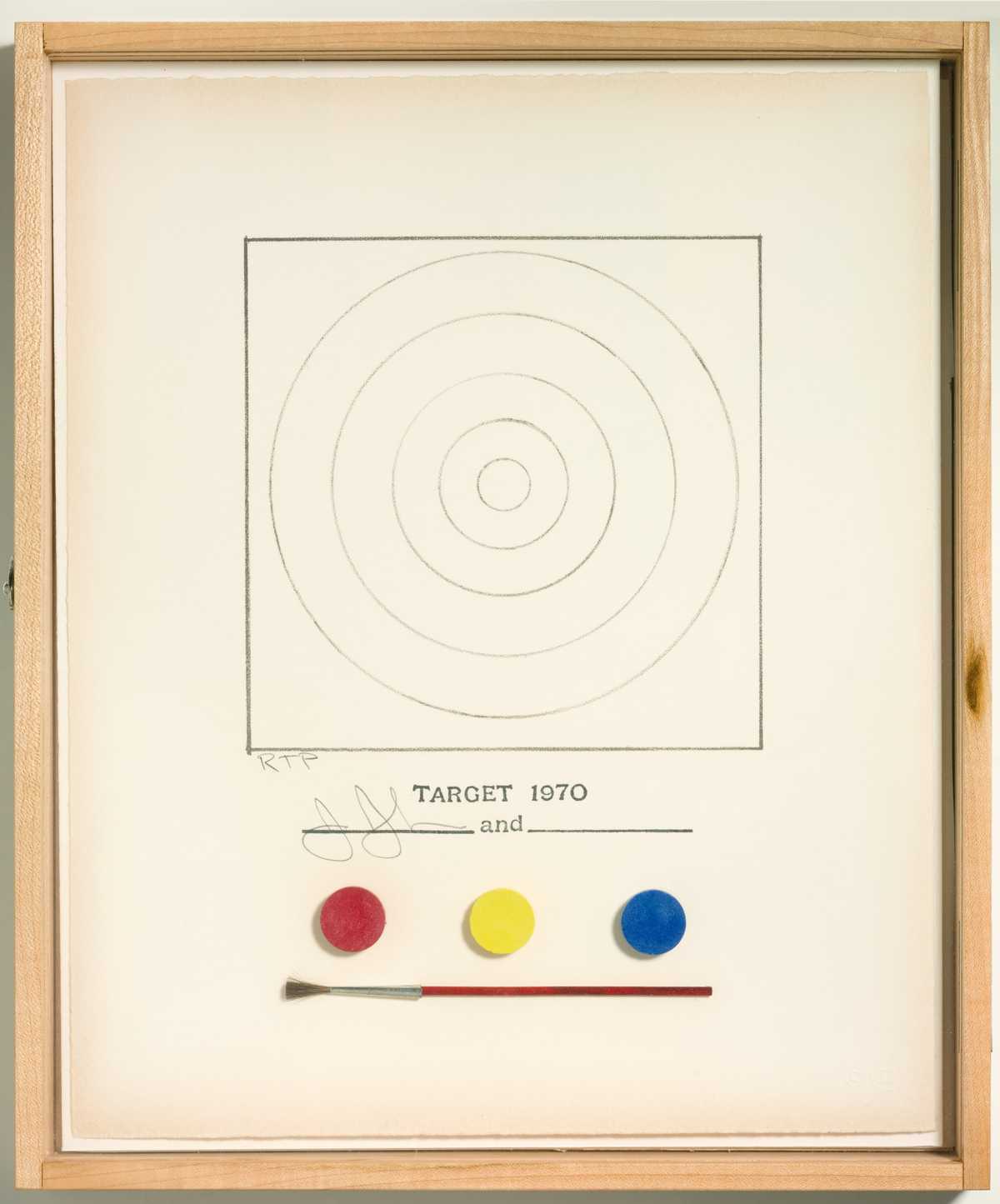

Jasper Johns, Gemini G.E.L., Target, 1971, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, Purchased 1973. © Jasper Johns. VAGA/Copyright Agency.

Sites of exposure and shade: Robert Rauschenberg’s formative rebellions

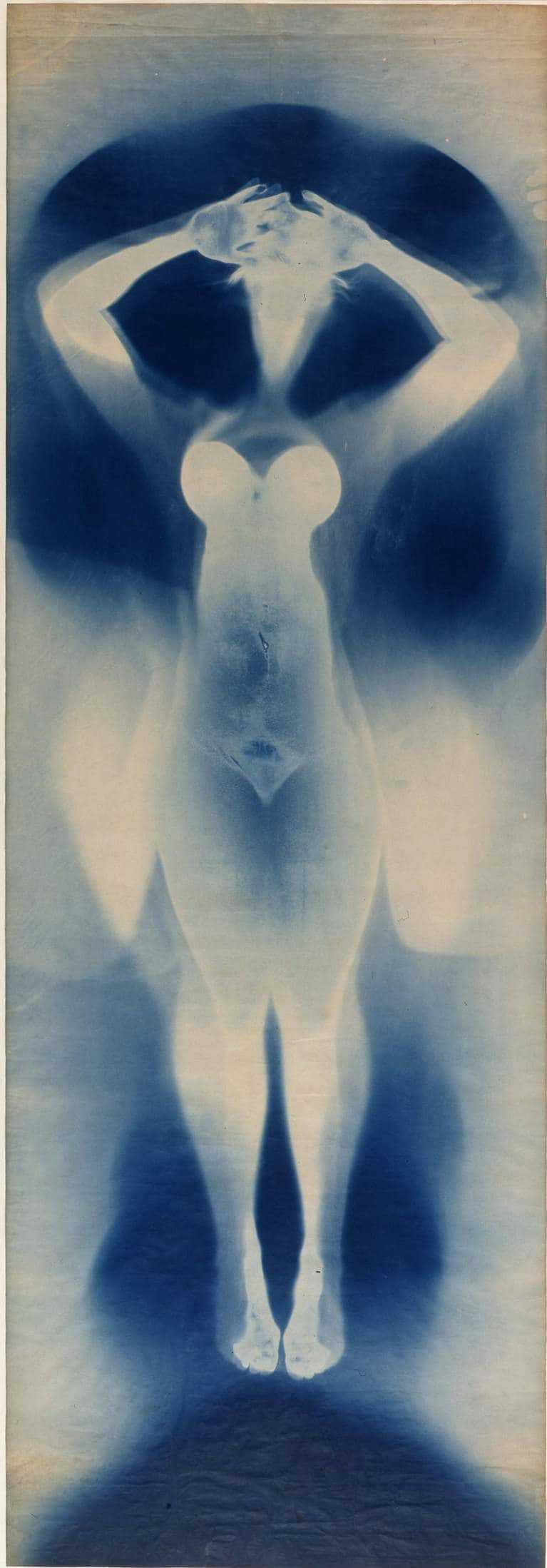

Robert Rauschenberg and Susan Weil, Female Figure c 1950, cyanotype, 265.7 x 91.1 cm. Collection of Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, Acc# 49.E001. Image courtesy Robert Rauschenberg Foundation. © Robert Rauschenberg / Copyright Agency, 2022 and © Susan Weil, 2022

Robert Rauschenberg and Susan Weil washing artwork with peroxide solution to fix image created by exposing blueprint paper to sunlamp, c 1951, gelatin silver print, 20.3 x 25.4 cm. Image courtesy Shutterstock © photographer Wallace Kirkland / The LIFE Picture Collection

Before meeting Johns, Rauschenberg preferred the input of close friends and partners over the formal instruction and critique provided by institutions. He challenged his schools and teachers, and the established traditions that they often represented. It was from this resistance that Rauschenberg, with the assistance of friends, came to formulate artworks that eschewed the artist’s hand and instead pursue ideas of exposure.

In 1948, Rauschenberg left his government-supported study at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière and Académie Julien in Paris after sensing that the European traditions of art were ‘big trees’ that ‘created a lot of shade’.10 This desire to move away from established traditions saw him return to the United States in the same year and seek out the most progressive art school at the time: Black Mountain College. Believing that he lacked focus, Rauschenberg sought out the school for the tutelage of Josef Albers, the Bauhaus master and colour theorist, who was renowned as an austere disciplinarian. Yet Rauschenberg often subverted Albers’s teachings, much to his teacher’s consternation. Albers ‘thought he was a bad boy … he didn’t like his irreverence’ and would often reprimand the young artist.11 Rauschenberg would later recall that Albers’s teaching was ‘total intimidation [and] abuse’ that left him cautious of mixing colours on canvas.12 Yet Rauschenberg leveraged this experience to explore ‘the wrong direction … a direction that was opposite to him [Albers]’.13

It would be his close friends at Black Mountain, including his then-wife, the artist Susan Weil, and the composer John Cage, who would inform his early practice. Weil introduced him to cyanotype prints, a method of exposing photosensitised paper to light to turn it a deep Prussian blue, with white areas leaving indexical traces of objects and shadows. Rauschenberg and Weil made collaborative cyanotypes by having friends pose on the delicate blueprint paper, which they would expose using a handheld sunlamp—capturing life-size impressions of the human form, turning shadows into images. As a photographic medium that relies on exposure to light, cyanotypes are conceptually linked with ideas of exposure and visibility. One of Rauschenberg and Weil’s well-known cyanotypes, Female figure c 1950, demonstrates how they considered this. This work was modelled by Rauschenberg’s close friend Pat Pearman at a time when she was hiding from an abusive partner: ‘She was at our house, crawling around on her hands and knees … she didn’t want anybody to see her from outside [the ground-floor window] because supposedly he was out there looking for her’, Rauschenberg said.14 Her naked body and raised arms are captured prostrate on the blueprint paper, though she can be identified only as a generic female figure, creating a sensitive portrait that contrasts the work’s creation through exposure with Pearman’s need to conceal herself from view. From these initial experiments in exposure, Rauschenberg would learn to see art as a site that could both reveal and conceal the world it inhabited.

![Robert Rauschenberg sits on a log on the floor with "White Painting [seven panel]" in the background](https://nga.gov.au/publications/significant-others/static/cf501b03701bc9358f2c2234f0cc8ac1/677e8/AA4_1.jpg)

Robert Rauschenberg with White painting [seven panel] 1951 and two Untitled [Elemental sculpture] (both 1953) at the Rauschenberg: paintings and sculpture exhibition, Stable Gallery, New York, NY, United States, Fall 1953. Image courtesy Robert Rauschenberg Foundation © photographer Allan Grant / Life Magazine

The ideas prompted by Weil’s cyanotypes, along with the disabling admonishments of Albers,15 led Rauschenberg to create his White paintings in 1951: a series of multi-panelled and singular oil on canvas works painted in pristine white. John Cage, who would meet and befriend Rauschenberg in May of that year, would immediately grasp the significance of their emptiness and they would inspire his notorious 1952 composition 4'33", which consists of only ambient sound, as the performer opens the lid of the piano and does not play a note for the duration of the performance. Cage would call the White paintings ‘airports for lights, shadows and particles’,16 while Rauschenberg would describe them as hypersensitive: ‘one could look at them and almost see how many people were in the room by the shadows cast’.17 These achromatic canvases weren’t exposures of himself, nor of his close friends like the earlier cyanotypes, but of a whole environment.18 They were a receptive surface for the world around them and reflected the space that they were shown in.19 Rauschenberg wrote of the works: ‘It is completely irrelevant that I am making them—Today is their creater [sic]’,20 suspending his role as the author of the work and allowing the viewer to consider the environment of the work as integral to its meaning. These works attracted immediate criticism from the Black Mountain College community,21 and this would compel Rauschenberg to form a creative pact. His close friend John Cage had a ‘fantastic influence’ on his thinking: Cage adhered to Zen Buddhist beliefs that nothing is either good or bad, beautiful or ugly,22 which gave Rauschenberg ‘permission to continue [his] thoughts’ despite the continuous criticism of these paintings.23 An agreement was reached between the two artists during the early years of their friendship, that they ‘could not be dependent on anyone’s opinion’ if they were to make experimental work, and that they needed to develop an almost total indifference to the opinions of others and a firm conviction in themselves to continue.24 Rauschenberg took this to heart and declared the White paintings his first mature works.25 This pact with Cage would introduce Rauschenberg to the notion of multiple audiences, as the difference between public opinion and that of a limited audience of queer friends became clear.

Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns in Johns’s Pearl Street studio, New York, NY, United States, 1954, gelatin silver print, 20.3 x 25.4 cm. Image courtesy Robert Rauschenberg Foundation © photographer, Rachel Rosenthal

Productive anonymity: when Rauschenberg met Johns

It was through a friend, the artist Suzi Gablik, that Jasper Johns first met Robert Rauschenberg in late 1953. Johns had abruptly left art school after an unexpected bout of illness and had resigned himself to painting only on Sundays.26 But as Rauschenberg and Johns’s personal relationship developed, so did their artwork: a transformation occurred in both their practices that was enabled by their mutual support of each other.

Rauschenberg and Johns shared a similar lived experience: both were born in the southern United States, grew up with very little exposure to ‘fine’ art, and had found a means to change their circumstances through the postwar GI Bill that financially supported war veterans to pursue higher education.27 Rauschenberg had been drafted to work on medical wards for the Navy during the Second World War and Johns served in the Army during the Korean War from 1951 to 1953. As young artists, they found themselves living in New York on the periphery of the community of Abstract Expressionists, and for some time they mingled with them in the public spaces that they frequented, such as the Cedar Tavern or the Artist’s Club. But the Abstract Expressionists tended to view the pair as an oddity.

Biographer Calvin Tomkins recalled of Rauschenberg that ‘for a long while, he was on the fringes of the art world. He was considered an amusing kid by most of the AbEx people.’28 From their peripheral position Rauschenberg and Johns came to understand the Abstract Expressionist movement as performative and public, with what Rauschenberg referred to as an ‘exaggerated emotionalism’—a movement fixated upon revelations of the authentic self that they simply could not participate in.29 As Johns would say: ‘I didn’t want my work to be an exposure of my feelings. Abstract Expressionism was so lively—personal identity and painting were more or less the same.’30

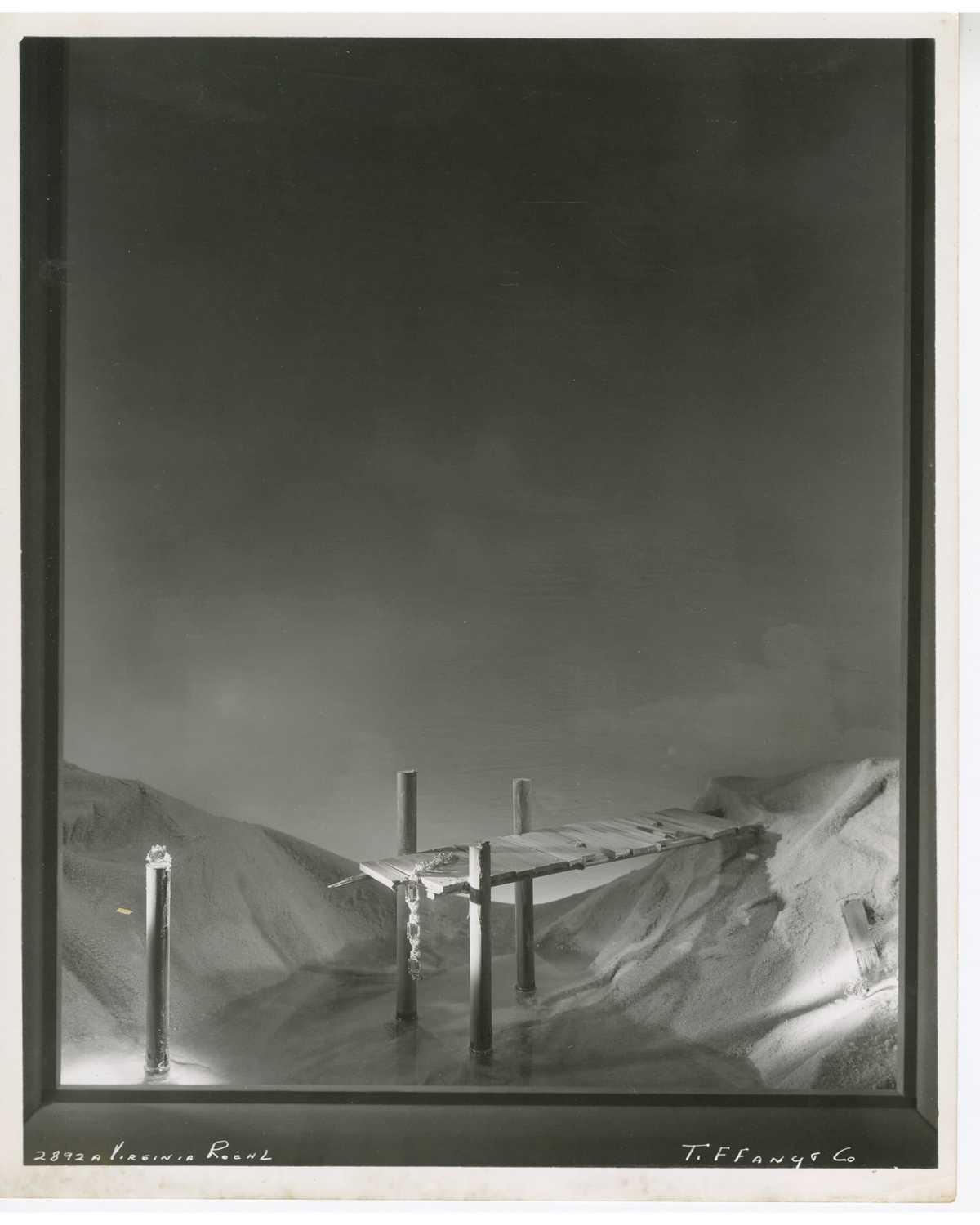

A Matson Jones window display. Image courtesy and © Tiffany & Co.

Instead of collaborating with the community of Abstract Expressionists, Johns and Rauschenberg colluded: ‘Jasper and I used to start each day by having to move out from Abstract Expressionism,’ said Rauschenberg, ‘We were the only people who were not intoxicated with [them].’31

Moving into adjacent New York studios on 278 Pearl Street in September of 1955, Rauschenberg encouraged Johns to quit his job at Marboro Book Stores and start taking himself seriously as an artist. The pair agreed to take on paid work only when it was really needed, dressing the Bonwit Teller department store windows under their collaborative pseudonym Matson Jones.32 What was significant about this period was the confidentiality between the two artists: they would see each other every day for a period of about five years, and Rauschenberg, as Johns recalls, became ‘totally unconcerned with his success’.33

Rauschenberg’s Stable Gallery exhibition, which featured his White paintings, had opened in September 1953 only to receive a series of negative reviews, yet Rauschenberg saw this as an opportunity, later commenting: ‘My first big break was that nobody took me seriously’.34 No longer affiliated with a gallery, Rauschenberg began to work almost exclusively with Johns, and Johns recalled that this was a lightbulb moment for the pair: ‘something happened’.35 They began to work in private, exchanging ideas, criticisms and physical materials. They would even assist in creating each other’s artworks. As Johns remembered: ‘The kind of exchange we had was stronger than talking. If you do something, then I do something.’36 This cloistered creative environment enabled Johns and Rauschenberg to freely experiment without public criticism and this led to artistic innovations for both artists. While their dialogue was private, their work remained engaged with ideas of public reception and understanding, developing methodologies that interrogated ideas of cultural value, legibility and private communication.

Robert Rauschenberg, Dirt painting (for John Cage) c 1953, dirt and mould in wood box, 39.7 x 40.2 x 6.4 cm. Collection of Robert Rauschenberg Foundation. Image courtesy © Robert Rauschenberg / Copyright Agency, 2022

Robert Rauschenberg, Untitled (gold painting) c 1953, gold leaf on fabric and glue on canvas, in wood and glass frame, 31.1 x 32.1 x 2.9cm. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum joint bequest of Eve Clendenin to the Museum of Modern Art and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Image courtesy of Art Resource 1974 © Robert Rauschenberg / Copyright Agency, 2022

One of Rauschenberg and Johns’s first collaborative exchanges investigated ideas of value. Rauschenberg’s series of ‘paintings’, made with the assistance of Johns in 1953, explored ‘a cultural hierarchy of values’, as the scholar Jonathan Katz notes.37 Working in a consistent rectangular format, the artists made each work from a different material: dirt, paper or gold. Rauschenberg predicted that despite their equal treatment as artworks, only the gold paintings would elicit a positive response and the paintings incorporating more common materials would be disregarded.38 This proved to be true, as only one of the dirt paintings now survives (it was owned by John Cage), while ten of the original gold paintings still exist. Motivating this series of works was Rauschenberg’s conviction that ‘there’s no such thing as “better” material’,39 only ascribed or inherited cultural values.

During this period, Rauschenberg’s work dramatically shifted from the achromatic White paintings to an extravagant method of uniting a range of materials. Johns would name these Rauschenberg’s ‘Combines’. The early Combines are significant as they both reveal and conceal elements of Rauschenberg’s biography within an overall composition that is hard to decipher. Rauschenberg considers Untitled c 1954 to be his first Combine: this three-dimensional work incorporates biographical content, such as newspaper clippings about his family and personal photographs, alongside numerous impersonal collage elements. Photographs of his former partner Susan Weil, his parents, and Jasper Johns, all occupy the work’s surface, as does a drawing by his first same-sex partner, the artist Cy Twombly. Focusing on these parts of the work might generate a reading about the artist’s personal relationships, but the strange and seemingly impersonal elements of the work, such as a decorative column, a mirrored surface, castor wheels and a taxidermy Dominique hen, complicate a reading of Rauschenberg’s authorial intentions. Speaking with art critic Barbara Rose, Rauschenberg saw this work as a means of reconciling himself with the world around him:

I come to terms with my materials. They know and I know that we’re going to try something … If that moment can’t be as fresh, strange and unpredictable as what’s going on around you, then it’s false.40

Robert Rauschenberg, Untitled c 1954, Combine: oil, graphite, crayon, paper, canvas, fabric, newsprint, photographs, wood, glass, mirror, tin, cork, and found painting with pair of painted leather shoes, dried grass, and Dominique hen on wood structure mounted on five casters, 219.1 x 97 x 66 cm. The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, the Panza Collection. Image courtesy of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles © Robert Rauschenberg / Copyright Agency, 2022. Photographer: Brian Forrest

The ‘fresh, strange and unpredictable’ elements of this work prevent it from cohering to a singular narrative about family, relationships or love. Instead, they give Untitled a relative inscrutability, an instability that might be seen as a form of queering, a pushing away from any fixed or stable meaning. Our eyes can move across the rich surface of this work to read it parts in countless ways that defy wholeness and mask clear authorial intent, allowing us to create own meanings. Untitled achieves what Rauschenberg would call a ‘productive anonymity’,41 the artist’s idea that ‘whenever I work successfully, I feel I become invisible’.42

Jasper Johns, Flag 1954–55, encaustic, oil and collage on fabric mounted on plywood, three panels, 107.3 x 153.8 cm. Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Philip Johnson in honour of Alfred H. Barr, Jr © Jasper Johns / Copyright Agency, 2022

For Jasper Johns, his relationship with Rauschenberg and their artistic exchanges were a point of origin for his artistic career. Five years Rauschenberg’s junior, Johns had not officially exhibited before they first met, and chose to destroy any work in his possession made prior to his 1954 painting Flag. This work, at one point partially painted by Rauschenberg, was transformative for Johns. This adaptation of the American flag was painted in encaustic, a seldom-used method of painting with pigment suspended in a melted beeswax. The flag was painted over a ground of newspaper fragments. The all-over composition and flatness of the work gave this national symbol a rigidity that would astonish and frustrate audiences. Johns would describe how the idea to paint Flag came to him in a dream, and he would evade questions as to the work’s meaning. What is known is that Johns intended the work to be overlooked, to ‘not require a special kind of focus, like going to a church … [but] to be looked at the same way you look at a radiator’.43 The familiar sight of the American flag in the patriotic 1950s led Johns to investigate creating a work that could be seen but, because of its familiarity, passed over. This idea of something seen but overlooked would continue throughout Johns’s art for many years and reflected the circumstances of his private dialogue with Rauschenberg, where they would create work without a public audience. Flag would be seen only four years after its creation, at his debut exhibition at Leo Castelli Gallery in 1958. Johns would reflect that ‘most young artists worked in a social setting where everyone knew what everyone else was doing. But my work took shape without many people’s knowing about it’.44 Similarly, Rauschenberg would reflect that

it was one of the few times that I found living in the shadows to be an advantage. By the time anybody realised that maybe I was serious, it was too late for anybody to do anything about it.45

Rauschenberg and Johns’s extensive period of private creative dialogue would come to an end in the late 1950s, as they began to exhibit with Leo Castelli Gallery, where their art would be met with both admiration and revulsion. The increased public discourse around their works would lead to discouraging remarks from critics, whose barbed attacks would inspire Jasper Johns to continue investigating the idea of a private language.

In February 1959 the conservative art critic Hilton Kramer wrote a critique of Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg’s work in the exhibition Beyond painting at The Alan Gallery, New York. According to Kramer, theirs was an art that aimed ‘to please and confirm the decadent periphery of bourgeois taste’, and, in a veiled reference to their commercial work as Matson Jones, ‘was akin to window dressing for department stores’.46 Rauschenberg’s work was singled out for combining what Kramer refers to as ‘the official good taste’ found in Abstract Expressionism with ‘nasty’ decoration. In response to Kramer’s article, Jasper Johns wrote:

Well thank god art tends to be less what critics write than what artists make. Because of that, no number of slipshod generalities and no abundance of false labels will establish the witless hierarchy that Mr Kramer suggested.47

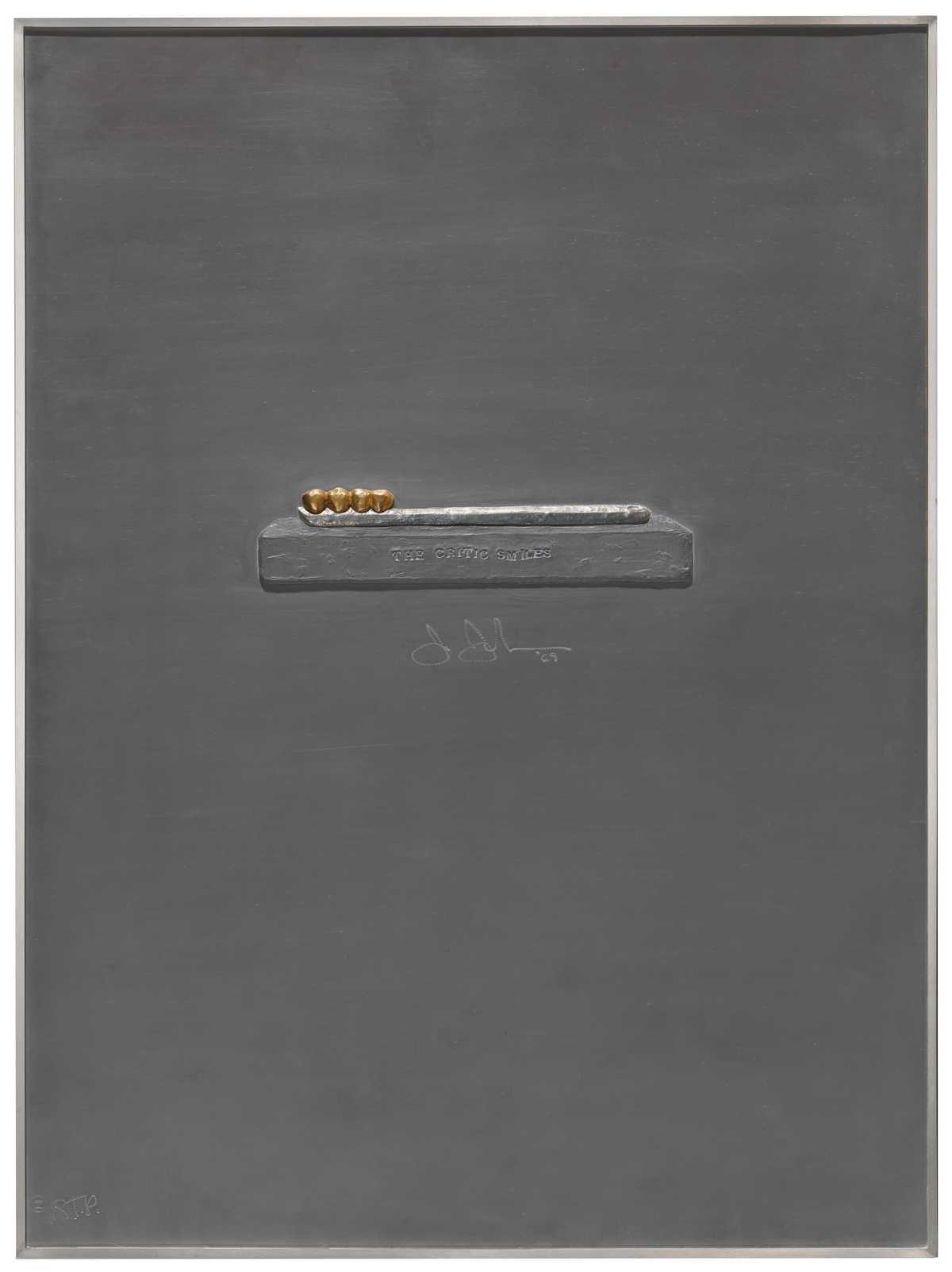

Jasper Johns, The critic smiles 1969, from Lead reliefs series, sheet lead relief, tin relief, gold casting, 58.6 x 43.2 cm, published by Gemini Graphic Editions Limited, Los Angeles. National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1973. © Jasper Johns / Copyright Agency, 2022

Sarcastically, Johns thanked the critic for ‘the generous allowance that artists may do whatever they please’.48 This public confrontation between artist and critic took place in the year after Johns and Rauschenberg surfaced from their private dialogue and their art re-entered public discourse and attracted the disapproval of critics. That same year Jasper Johns created a puzzling sculpture of a toothbrush with teeth for bristles, and the word ‘copper’ imprinted on the handle. He titled it The critic smiles 1959. When quizzed many years later by the writer Michael Crichton about the work, the usually evasive artist revealed that:

I had the idea that in society the approval of the critic was a kind of cleansing police action. When the critic smiles it’s a lopsided smile with hidden meanings. And of course, a smile involves baring the teeth. The critic is keeping a certain order, which is why it is like a police function. The handle has the word ‘copper’ on it, which I associate with police.49

Johns’s intent to ridicule public criticism as a policing of official good taste is camouflaged in a symbolism that only the initiated would understand: The association of gold teeth with criticism would evade the comprehension of most viewers, as would a toothbrush being associated with policing. Instead of conveying a message through known and commonly understood metaphors, Johns employs metonyms, where what is depicted (a toothbrush) can be understood as something else (‘keeping order’ and cleaning), which can then be taken for something else again (policing). The associative reasoning employed in using metonyms assists in the creation of a private language: The work is clearly a response to the normalising criticism of figures such as Hilton Kramer and was likely made by Johns in defence of Robert Rauschenberg. But until Johns’s explanation of the work to Michael Crichton, it was intended to be understood only by his partner of six years.

Johns professed that his art had a focus on a thing ‘becoming something other than what it is’.50 In an artist statement from the same year as The critic smiles, Johns relayed his growing fascination with Marcel Duchamp’s idea of ‘transfer[ring] from one like object to another the memory imprint’.51 This method of camouflaging a work’s meaning in the privacy of metonyms would continue throughout Johns’ practice, and was a technique developed during his relationship with Rauschenberg. The public interpretation of his works would bemuse Johns in the years that followed: ‘If an artist makes … chewing gum and everybody ends up using it as glue, whoever made it is given the responsibility of [having made] glue’.52

Rauschenberg and Johns’s private dialogue radically altered their practice by ‘giving permission’ to one another during a time when a public audience would have refused to do so. It is no coincidence that Rauschenberg and Johns’s relationship would end in 1961, a couple of years after they had begun to publicly exhibit their work again. Rauschenberg would attribute their breakup to the sudden increase in public attention they received: ‘What had been tender and sensitive became gossip’ for both artists and they parted ways over the ‘embarrassment about being well known’.53 Johns would reflect that he learnt more from their relationship than ‘from any other artist or teacher, and working as closely as we did and more or less in isolation, we developed a strong feeling of kinship’.54 The pair’s fallout meant that the artists would only occasionally cross paths over the decades to come, as they continued their parallel artistic careers. While their work continued to evolve, both Rauschenberg and Johns retained the artistic methodologies developed within their early creative dialogue, where each was the private audience for each other.

Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg at Gemini GEL in Los Angeles, 1980, gelatin silver print, 20.3 x 25.4 cm. © photographer, Terry Van Brunt

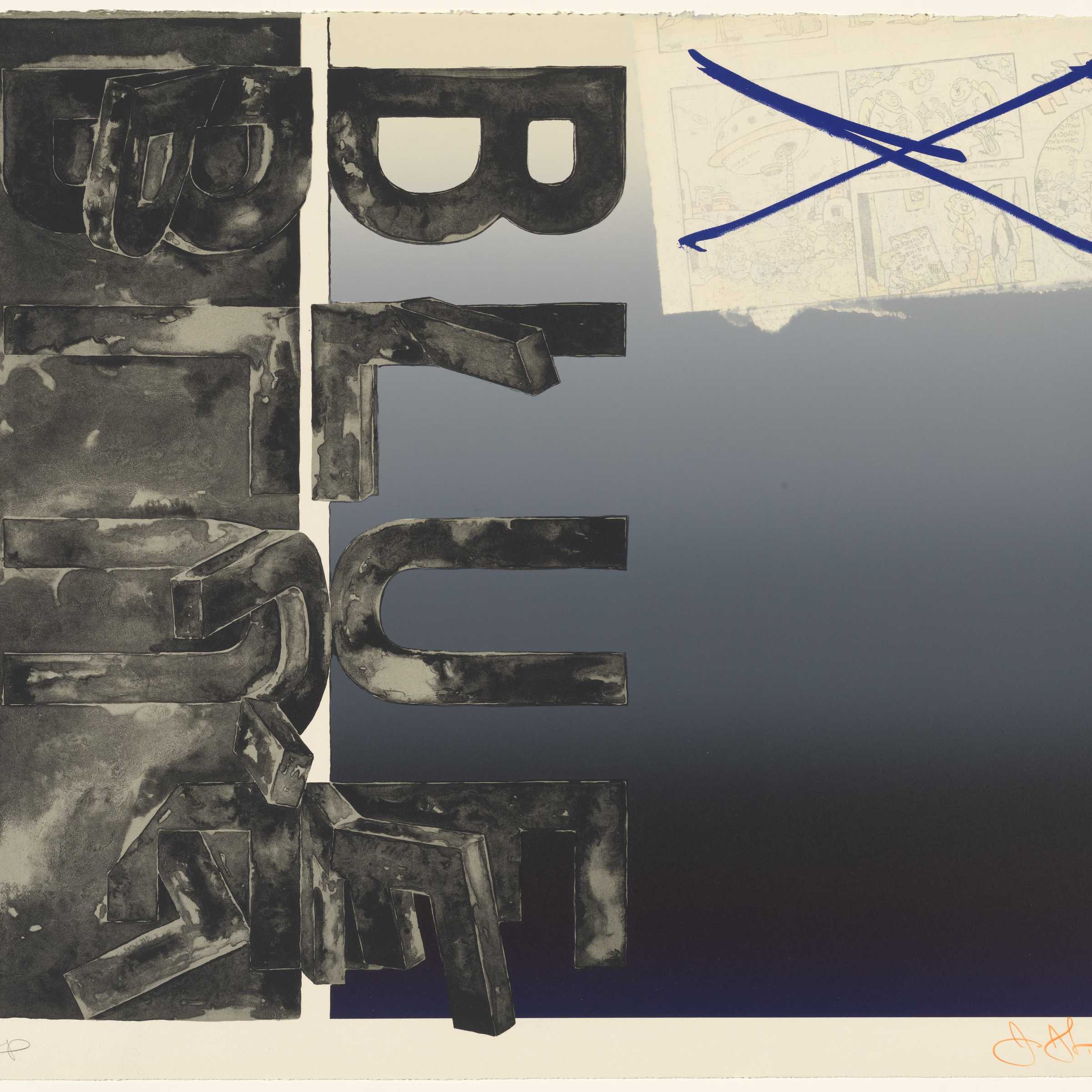

Header image: Jasper Johns, Bent “Blue” 1971 (detail), from Fragments–according to what series, lithograph and newspaper transfer, 64.6 x 73.4 cm, published by Gemini Graphic Editions Limited, Los Angeles, purchased 1973. © Jasper Johns / Copyright Agency, 2022

Notes

- — ‘[T]he encouragement that they got from each other, personally and professionally, gave them “permission” as Rauschenberg once put it, “to do what we wanted”.’ Calvin Tomkins, Off the wall: A portrait of Robert Rauschenberg, Picador, New York, 1980, p 108.

- — Jasper Johns interview in Barbaralee Diamondstein-Spielvogel, Inside the artworld: Conversations with Barbaralee Diamondstein, Rizzoli, New York, 1994, republished in Jasper Johns, Kirk Varnedoe and Christel Hollevoet, Jasper Johns: writings, sketchbook notes, interviews, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1996, p 298.

- — 'His heart belongs to Dada’, Time, vol 73, no 18, 4 May 1959, p. 58.

- — Robert Rauschenberg, ‘Random order’, Location, vol 1 no 1, Spring 1963, pp 27‒31.

- — Jonathan Katz, ‘Lovers and divers: picturing a partnership in Rauschenberg and Johns’, Frauen Kunst Wissenschaft, no 25, June 1998, p 16.

- — Vivien Raynor, ‘Jasper Johns: I have attempted to develop my thinking in such a way that the work I’ve done is not me’, Artnews, 72, no. 3, March 1973, p 21.

- — See Moira Roth, ‘The aesthetic of indifference’, Artforum, vol 16, no 3, November 1977, pp 46–53.

- — A term first used in relation to both men’s work by Jonathan Katz in ‘Lovers and divers: picturing a partnership in Rauschenberg and Johns’, p 28.

- — Tomkins, Off the wall, p 285; Jo Ann Lewis, ‘Jasper Johns, personally speaking’, The Washington Post, 16 May 1990, viewed 17 November 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1990/05/16/jasper-johns-personally-speaking/dd4fe36a-f512-4811-819f-ffb0c04bee72.

- — Barbara Rose, Robert Rauschenberg: an interview with Barbara Rose, Elizabeth Avedon Editions, New York, 1987, p 21.

- — Karen Thomas, unpublished interview with Kenneth Tyler, master printer, 9 August 2012, Robert Rauschenberg Oral History Project, Robert Rauschenberg Foundation archives, p 32.

- — Rose, Robert Rauschenberg, p 25.

- — Mary Lynn Kotz, Rauschenberg: art and life, Harry N Abrams., New York, 1980, p 267.

- — Rose, Robert Rauschenberg, p 21.

- — Rauschenberg recalled that Albers’s strict methods for teaching colour theory had a role in formulating this: ‘Actually the “white paintings” came directly out of [Albers’s] schooling. He taught me such respect for all colors that it took me years before I could use more than two colors at once.’ See Rose, Robert Rauschenberg, p 23.

- — John Cage, ‘On Robert Rauschenberg, artist, and his work’, Silence, Wesleyan University Press, Middletown, CT, 1961, p 102.

- — Tomkins, Off the wall, p 64.

- — The writer Branden W Joseph maintains that Cage interpreted Rauschenberg’s White paintings in this manner due to his familiarity with László Moholy-Nagy’s 1928 text The new vision, in which Moholy-Nagy describes the plain white surfaces of Kazimir Malevich’s paintings as ‘an ideal plane for kinetic light and shadow effects … a miniature cinema screen’. See Branden W Joseph, Random order: Robert Rauschenberg and the neo-avant-garde, MIT Press, London, 2003, p 36.

- — The idea of a canvas being a receptive surface for the world around it became an obsession for Rauschenberg. One of his never-realised ideas was to make the walls of an entire room photosensitive, so that ‘the walls will absorb whatever images appear in that room’. See Rose, Robert Rauschenberg, p 77.

- — From a letter to Betty Parson, gallerist, Parsons Gallery, reproduced in Walter Hopps, Robert Rauschenberg: the early 1950s, exhibition catalogue, The Menil Collection and Houston Fine Arts Press, Houston, TX, 1991, p 230.

- — Hopps, Robert Rauschenberg, p 65.

- — Kotz, Rauschenberg, p 76.

- — Rose, Robert Rauschenberg, p 34.

- — Tomkins, Off the wall, p 66.

- — Rauschenberg wrote to the gallerist Betty Parsons of the works that ‘sobered up from summer puberty … Have felt that my head and heart move through something quite different’. See Hopps, Robert Rauschenberg, p 230.

- — Rose, Robert Rauschenberg, p 47.

- — World War II had a profound effect on the arts in America, not only with access provided to education through the GI Bill, but also via its influence on LGBTIQ life. As Michael Bronski notes, the acceleration of the movement of people around the nation as part of the war effort led to increased contact and the exchange of ideas that could challenge ‘the religious and moral upbringing of these men and women’ along with greater social freedoms. See Michael Bronski, A queer history of the United States, Beacon Press, Boston, 2011, p 156.

- — Raushchenberg oral history project: the reminiscences of Calvin Tomkins, conducted by Mary Marshall Clark, Columbia Center for Oral History Research, Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Archives, 21 March 2015, p 20.

- — ‘Robert Rauschenberg by Paul Taylor’, Interview, vol 20, no 12, December 1990, p 147. Rauschenberg remembers the 1950s as ‘a particularly hostile, prudish time’.

- — Vivien Raynor, ‘Jasper Johns: I have attempted to develop my thinking in such a way that the work I’ve done is not me’, Artnews, vol 72, no. 3, March 1973, p 21.

- — Kotz, Rauschenberg, p. 90; ‘Robert Rauschenberg interview by Paul Taylor’, Interview, p 147.

- — Matson was Rauschenberg’s mother’s maiden name, while ‘Jones’ was a corruption of ‘Johns’. The artists’ need for a pseudonym is thought to be due to the stigma of being seen as commercial artists.

- — Kotz, Rauschenberg, p 89; Grace Glueck, ‘Once established, Ideas can be discarded’, New York Times, 16 October 1977, p. 75

- — ‘Robert Rauschenberg by Paul Taylor’, Interview, p 147.

- — Michael Pye, ‘Behind veils, the elusive heart’, Independent on Sunday (London), 18 November 1990, reprinted in Johns, Varnedoe and Hollevoet, Jasper Johns, p 254.

- — Glueck, ‘Once established’, p. 75.

- — Jonathan Katz, ‘The art of code: Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg’, in Whitney Chadwick and Isabelle de Courtivron (eds), Significant others: creativity and intimate partnership, Thames & Hudson, London, 1993, p 198.

- — Hopps, Robert Rauschenberg, p 161.

- — Rose, Robert Rauschenberg, p. 58.

- — Ibid.

- — Joseph E Young, ‘Pages and fuses: an extended view of Robert Rauschenberg’, The Print Collector’s Newsletter (New York), vol 5, no 2, May–June 1974, p 26.

- — Ibid.

- — ‘His heart belongs to Dada’, Time, vol 73, no 18, 4 May 1959, p. 58.

- — Peter Fuller, ‘Jasper Johns interviewed’, Art Monthly (London), no 18, July/August 1978, p. 7-8.

- — Mark Rosenthal, Artists at Gemini G.E.L.: celebrating the 25th year, Harry N Abrams, New York, 1993, p. 158.

- — Hilton Kramer, ‘Month in review’, Arts Magazine, vol 33, no 5, February 1959, p 49; the reference to window dressing is likely done knowingly by Kramer, who may have been aware that Rauschenberg and Johns worked creating window displays for the department store Bonwit Teller under the pseudonym Matson Jones. The artists may have seen the commercial aspect of this work as detracting from their seriousness as artists. See Richard Meyer, ‘Rauschenberg, with affection’, February 2018, Essays, SFMOMA online, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, viewed 26 October 2021, www.sfmoma.org/essay/rauschenberg-affection/.

- — Jasper Johns, ‘Collage’ (letter to the editor), Arts Magazine, vol 33 no. 6, March 1959, p 7.

- — Johns, ‘Collage’.

- — Michael Crichton, Jasper Johns, Harry N Abrams, New York, 1977, p 42.

- — Gene R Swenson, ‘What is pop art? part II’, Artnews, vol 62, no 10, February 1964, p. 43.

- — Jasper Johns, artist statement, in Dorothy C Miller (ed), Sixteen Americans, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1959, p. 22

- — Gene Swenson, ‘What is pop art?’, p 66.

- — ‘Robert Rauschenberg interview by Paul Taylor’, Interview, p 147.

- — Jasper Johns interviewed by Paul Taylor, ‘SoHo’s avant-guardian’, Connoisseur, vol 221, no 956, September 1991, p 102.