Anne Dangar at Moly-Sabata

Tradition and Innovation

13 Jul – 28 Oct 2001

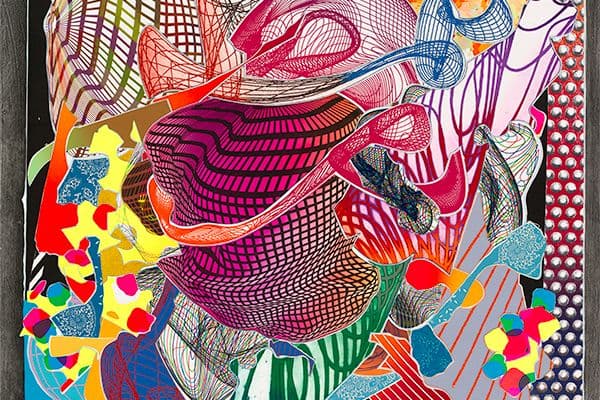

Anne Dangar, Gouache, 1936, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2002

About

A trip to France in 1926 with the Sydney painter Grace Crowley led to Dangar moving to France in 1930 to take up residence with the artists’ community led by Albert Gleizes at Sablons, situated on the River Rhône. She immersed herself in the subsistence lifestyle characteristic of traditional peasant existence, learning to produce glazed terracotta ware in the Gallo-Roman manner. In drawing upon these ancient vernacular ceramic traditions, Dangar produced an innovative model of domestic ware that married these forms with her own experiments in Cubist inspired decoration during the 1930–40s.

Curatorial Essay

Anne Dangar and Grace Crowley were students of André Lhôte in Paris from 1926–28. At the end of her stay in Paris, Dangar saw an exhibition at the Grand Palais that included some of Albert Gleizes’s paintings. This experience proved to be an epiphany for her, she described this moment as filling her ‘with a perfect satisfaction, with an internal joy that the Hindus call intellectual beatitude’. [1]

Grace Crowley contacted Albert Gleizes on Dangar’s behalf and was invited to visit the master at his home in Serrières, central France. Crowley met Gleizes and informed him that Dangar was fascinated by his work and that she hated being back in Sydney. Gleizes sent Dangar a telegram inviting her to become part of his artists’ cooperative at Sablons. Dangar did not hesitate, she arrived just eight weeks later without having received any detailed information about Moly-Sabata, the artists’ colony established by Gleizes and his wife. Later Dangar admitted that she had been under the impression that Gleizes had offered her a position at his art cooperative, instead she was expected to earn an income as well as contribute to the life of the community without any remuneration. Despite the hardship that she experienced at Moly-Sabata, her unshakeable belief in Gleizes as a master and theorist ensured her dedication and enabled her to develop an art form that would never have been possible had she stayed in Australia.

Moly-Sabata

Moly-Sabata is an 18th-century customs house on the banks of the river Rhône in the small village of Sablons. The house is made of stone and has a grand double, centralised staircase facing a large garden. The back of this grand house looks out onto the Rhône and has a rustic balcony with an iron balustrade reminiscent of those found in works painted by Matisse at Nice.

Moly-Sabata was established as a self-subsistence cooperative. The garden produced vegetables and fruit, and bees produced the honey that was used to barter for flour and other necessities. The artists were expected to earn their living by practicing various crafts. The locals often took pity on Dangar and brought her produce from their farms. The region is very beautiful, with orchards surrounding the village and vines and cherry trees flanking the hillsides opposite Sablons. Dangar slaved like a labourer to extract her livelihood from the earth but produced art as if she were a more privileged urban artist. Dangar’s letters are full of descriptions of her horticultural activities as well as her agricultural struggles, such as her combats with the beehives.

Why Smudgie if I didn’t think of the feeding of the bees, say every time necessary we ought to feed the bees, we ought to give the bees their blankets, we ought to buy straw paper and cover the honey, I warrant that the only work done regarding the bees in the whole year would be the taking of the honey. The strawberries (a continuous care) are never touched by anyone but this fool. [2]

At Moly-Sabata Dangar turned her back on urban culture and immersed herself in the peasant economy and a craft as ancient as civilisation itself. The gruelling physical labour made her scornful of artists in major cities such as Paris or Sydney. Dangar accepted manual labour as an article of faith and followed Gleizes’s demand that artists should return to the land: ‘le retour à la terre’, as he called it. Working with the most elemental materials – water, fire, earth, and air – and her immersion in the potter’s craft (at which she only arrived at the age of 40) made Dangar conscious of the mystical aspects of her profession. This return to first principles also encouraged her religious and spiritual zeal.

Albert Gleizes’s theories, as Dangar acknowledged, were couched in a prolix and abstruse language. Dangar was of the opinion that his painting was a truer example of his thinking rather than the numerous books and tracts. Gleizes’s teaching was of prime importance to her because it outlined the right path. Dangar absorbed the principles and translated them into a craft that was far more immediate and down to earth than her master’s paintings.

In La peinture ou de l’homme devenu peintre Gleizes wrote:

Painting by its nature is not a spectacle, nor an object seen via a point of perspective, it is instead its own object. There are three types of expression in objective painting: there is the pure work, without recourse to recollected or written history. There is the work which freely experiences recalled imagery by coincidental interrelation of melodic lines. Finally there is the work where an iconographic subject has been freely undertaken. [3]

Gleizes’s theories originated from Cubism’s initiation of a new pictorial space; the representation of reality as something the artist perceived. The Cubists reduced the pictorial space to a two-dimensional plane, eliminating illusionism and representing objects as geometric solids. Cubism negated the basis of western painting since the Renaissance, simultaneously allowing the articulation of planes and the juxtaposition of different views of the same object, giving a notional and perceptual view of an object. They argued that a painting was a self-sufficient entity independent of the external world, for which they coined the term un tableau-objet, the picture as the key subject.

The 1930s: Translation and Rotation

Gleizes’s study of primitive art led him to develop theories of art to bolster his essentially spiritual view of culture. He established a system based on a series of shifting planes, known as translation, which were activated by a dynamic, circular rhythm known as rotation. Gleizes based his theories on the Italian mathematician Fibonacci’s (1170–1250) observations of the growth patterns of plants.

An influence that Gleizes did not acknowledge was that of an American mathematician, Jay Hambidge. Hambidge demonstrated that all ancient art was founded on inherent geometric laws embodied in the principles of Dynamic Symmetry. This major organicist theory promoted the spiral form as the origin of all design. He analysed the geometric ratios of classical Greek vase design, also derived from the growth patterns of plants, and claimed that the spiral in nature is the result of continued proportional growth and is the natural embodiment of Dynamic Symmetry.

European and American artists applied Hambidge’s theories to their compositions. The principles of composition of classical Greek architecture, sculpture and pottery were transferred to abstract works of art. In Rhythmic Form in Art, art historian Irma Richter analysed works of art from the 15th century BC and found that the same laws applied to small items of pottery such as a kylix drinking vessel and to larger elements of monumental architecture such as the Parthenon. In her analysis of a kylix Richter wrote:

The two-dimensional painting partakes of the same scheme of proportion as the three-dimensional shape which it decorates, and the mysterious rhythm which controlled the whirling circles of clay on the potter’s wheel, shaping them into a thing of beauty, penetrated also into the design of the vase-painter. [4]

This statement accords exactly with Dangar’s own realisation about the nature of pottery. Dangar adopted the spiral as a central motif in her work.

The first diagram describes the overlapping of planes resulting in translation. The second diagram shows the planes revolving around an axis. Each plane is seen to revolve in an opposing direction, resulting in a sense of rhythm. According to Gleizes: ‘translation represented an unfolding of planes as seen against a square on the surface of a painting; rotation occurred when these planes began to shift around a central point.’ [5]

In 1922 Gleizes published La peinture et ses lois: ce qui devait sortir du cubisme, which claimed that western art reached a high point in the 11th and 12th centuries. Gleizes’s theory, like those of other utopian socialists, was anti-scientific and anti-industrial. He saw the Renaissance preoccupation with science as being destructive to humanity and accordingly isolated the invention of one-point perspective as a by-product of scientific thinking. Gleizes felt that the practice of perspective placed a high premium on the external world and on realism in art to the detriment of the inner world of religion and symbolic values. He argued that one-point perspective had forced painting to become static whereas in primitive art there was greater movement and rhythm. For Gleizes the major achievement of Cubism was that it disrupted Renaissance space in painting, thus shattering illusionism. He used the Cubist’s methods as a foundation for his own thesis, which was in opposition to the original beliefs of the Cubists; they were atheists and their radical departures from traditional painting were part of a wholesale reaction against the academy and tradition.

Dangar sent Grace Crowley books and articles written by Gleizes as well as her frequent correspondence containing extracts from Gleizes’s teaching. Before the 1930s (the period when Dangar joined him), Gleizes was working in a linear fashion without much emphasis on the interaction of colour. He began to apply simultaneous contrasts, attempting a dynamic interrelation of colours and incorporated la ligne gris into his compositions. The grey line added value to the colour elements in his compositions. The grey line, as he saw it, was a cadence – a term derived from music – which surrounded the passages of colour with a grey halo, helping to unify the composition and to project the colour. Gleizes’s cadences were groups of colour designed to make the eye travel along the picture plane so that colour could motivate the eye just as translation and rotation had. He issued many directives to his pupils about successful application of cadence in their work, and Dangar repeats many of these observations in her letters.

Dangar found that the rhythmic motion and circular movement of her pottery wheel not only reflected Gleizes’s notions of rotation and translation, but also corresponded with Cubist composition, as it was the movement of form and colour that created the picture.

Towards the end of her life Dangar wrote that Albert Gleizes represented, ‘the hope of the return of a spiritual epoch, just as Leonardo da Vinci was a reflection of our material epoch so correspondingly Gleizes is the prophet chosen by God’. [6]

The Children of Sablons-Serrières and Anne Dangar

Dangar wove Gleizes’s principles into her pottery, her life and into her teaching. Even the children of Sablons-Serrières were taught the basic principles in a practical way. The colours of the rainbow were analysed by Dangar and applied to the flowers of the field so that the children could relate colour theory to nature. She taught them to look for ‘this movement in order, unity, colour, light and rhythm . . . in nature and hills and trees’.

In the classroom, we draw bouquets of flowers made with every motive and sometimes we make them with very big paper découpé. At home they make pictures about a subject that was chosen during the lesson. I always try to interest them in local subjects (the Sablons fair, the butter market before German occupation, the opening of the fishing season, etc.) or local historical subjects, actual seasons, circular work of the earth (cyclic work according to the rhythm of the seasons) etc., subjects in time. [7]

Dangar did not think that any of her students would become artists but she wrote that she hoped to give them a little more interest and joy in life. She often described her role as a teacher of children, and believed that it was an important extension of her work as an artist. Dangar saw it as her own special contribution to Gleizes’s program, thinking that by educating the youth of the region she could influence them to perpetuate her theories about art and life.

Anne Danger the Potter

Dangar started her career as a painter but her vocation was changed irrevocably by her move to France. In fact, had she remained a painter we probably would not have heard of her. For the first few months at Moly-Sabata, Dangar was set the task of completing pochoirs (a stencilling technique that allows a design to be repeated on various surfaces) after Gleizes’s designs with the painter Robert Pouyaud, who was well practised in this medium. The pochoirs followed Gleizes’s schematic, violin-shaped motif based on the overlapping forms of Analytical Cubism. The pochoirs were also a source of revenue, Gleizes sold them to his dealer Povolozky in Paris. Gleizes gave Dangar a commission for 400 pochoirs which she struggled with, since Gleizes was very particular about their design.

The pochoirs’ form derived from a medieval card game; they were created by zinc stencils and were printed in a primitive manual technique. The paintings by Dangar from 1936 reveals how practised she became in this medium. The forms are superimposed in planes and the colours progress from dull yellows and greens to more resonant colours such as red, violet, and yellow which is juxtaposed with its complementary blue. The lines of the circular forms are broken on the periphery to denote rotation. All of Gleizes’s pupils produced pochoirs – the vocabulary of Gleizes’s paintings. Grace Crowley produced some pochoirs under Dangar’s directions. In one of her early letters Dangar gave Crowley the recipe for the gouache that was used in their production. There is also one example of a pochoir by Dorrit Black who visited Moly-Sabata briefly during Dangar’s residency there.

As Dangar described at length to Grace Crowley in 1931 when she was doing her third colour gouache for Gleize:

I don’t feel that Gleizes’s is the only method of painting or the last word by any means, but I think he has touched the reason why painting is such a life absorbing thing and with his principles one could choose a thousand roads leading up to – God? Je ne sais pas but it’s where we want to go. This method of building in pure colours instead of following a fancy scheme of safe greys leads one to make terrible poster like things at first but I already know I have gained power. [8]

Although Dangar expressed an early interest in folk pottery when she was a student in Paris, she only studied briefly with Henri Bernier, a Normandy potter from Viroflay near Sèvres. In 1927 Dangar wrote a letter to Crowley’s mother describing the joy she took in making pottery. Later she wrote to Crowley:

We make a fire of charbon du bois (wood coal) in the middle of the pottery and I bake potatoes for my lunch in the ashes or chestnuts or barcelona nuts and make toast and we heat bricks for our feet when we have to sit and decorate or put handles on. It’s wonderful how happy I am with these simple folk who are good and honest and interesting. [9]

In 1930 she wrote that she was taking lessons from ‘the drunken potters of St. Désirat’, where she went several times a week. Her first experiments in pottery were tobacco jars followed by plates and pitchers. She sold her first pots at the Serrières market and one of her pots was purchased by the museum at Cavalaire. [10] As she improved in technique Dangar began to frequent other potteries in adjoining villages such as St. Vallier, Roussillon, St Uze and eventually Cliousclat.

Pouyaud introduced Dangar to the Nicholas family of potters at St. Désirat as he was concerned about Dangar’s material welfare at Moly-Sabata and thought that if she could produce useful items of pottery this would help her to survive financially.

Dangar was very excited about her first pottery lessons. The initial attempts were crude and heavy. They followed the local idiom of glazed terracotta, each pot was covered by a yellowish engobe (slip) and decorated with simple floral motifs in green and red. These early efforts are all designed to correspond to local taste and are therefore honest and rugged. Dangar began to go farther afield to professional potteries in other villages such as Roussillon, a large centre that had several potteries at the time. There she worked with a potter called Henri Bert, after he died she worked with Paquaud who threw and turned large pots for her on demand. Dangar decorated these pots according to Gleizes’s designs as well as elements of Celtic art.

In 1934 Dangar began to visit the pottery at Cliousclat, a large traditional pottery 64 kilometres from Mirmande, the Romanesque hilltop village where she had spent the summer of 1928 as a student of André Lhôte. Mirmande and Cliousclat were her favourite places. The Cliousclat pottery had continued uninterrupted since the beginning of the 18th century; it was an established pottery and had numerous workers. Dangar commissioned large platters so she could decorate them with images derived from Gleizes’s paintings. Dangar’s pottery forms became more confident. She studied Gallo-Roman designs in libraries and in books that Gleizes lent her. Her ability to immerse herself in the styles of preceding eras meant that her pots were based on a strong idea of tradition, evolving out of shapes that had been passed on through the centuries. Dangar drew for Paquaud a series of basic shapes for large pots. She did not have the strength to throw a pot of 15 or 20 kilograms so all she had to do was to point to number 1, 2, or 3 and the potter would execute the shell for her. Dangar’s schema can be seen today next to one of the wheels at what used to be Paquaud’s pottery.

Dangar’s letters frequently mention the difficulties she had using other potteries.

Taxes, bus fares, etc. are all getting so high that although I work like mad and have lots of orders I can’t earn enough to buy my winter coal. I’ve counted up and find I spend nearly 30 francs a day in fares and sleeping in Roussillon. That’s 1,500 francs per year that I’d save if I had a kiln here. And shoe leather? Today (as often) I have walked 14 kilometres . . . I’m sure I’d save half this expense if I had a kiln. And TIME? Time in all its senses! Three hours a day lost in travelling! The right time to change planks, put on handles, etc. etc. etc. And to work in rhythm at Moly instead of working to the cursing and swearing of those drinking communists. [11]

Dangar lived like a nun at Moly-Sabata, which was cloistral but less well-appointed than most convents. Dangar was so committed to Gleizes’s ideals that she was prepared to labour all day long, and inevitably other people’s work ethics, such as those of the other potters, were judged harshly by her.

When we take into account all the hardships it is something of a miracle that Dangar was able to produce pottery of such a high standard of inspiration. Her intuitive approach and decoration has a richness and confidence about it that makes it appear to have a perfect nexus with the underlying forms. Dangar probably applied Gleizes’s theories more successfully than his painting disciples since she had to translate his abstract designs onto a three-dimensional pot which had its own rationale as a practical everyday object. Dangar’s designs did achieve a balance with the underlying pot and as her work developed the forms correspondingly multiply and become more complex.

The early work tends to be stolid and thick, the decoration is relatively simple as in a milk jug decorated with green and brown spirals and other free floral arabesques. A plate of the late 1930s demonstrates how she began to articulate the surface, in this case with a pochoir design which shows the superimposed rectangles and overlapping patterns to produce a rhythmic composition. The later works like the storage jars and large platters demonstrate a fusion of craft and theory. The storage pot with Celtic designs reveals how Dangar has thoroughly integrated the surface design with the rounded movement of the pot. The snake-like forms reflect Gleizes’s admiration of Celtic art in its purity and rhythmic flow.

Dangar’s creative efforts were not entirely dominated by Gleizes. She was able to seek out influences for herself such as that of Moroccan art. In 1939 Dangar was invited to Fez by the French government, on the suggestion of a young friend, Maurice Grimaud, who was secretary to the Governor there. The Governor and his wife wanted to encourage Moroccan artisans, in particular the potters, who had lost touch with their great tradition. Dangar was invited give the potters lessons in design related to their own heritage. She returned to Moly-Sabata and began to improvise with Arabic forms, creating many coffee and tea sets with Arab-style bulbous handles and vegetable-like lids.

Like the traditional potters, Dangar used natural glazes for her pottery. The yellowish colour of the ground was obtained by an engobe made of alquifoux, a mix of lead and clay from Bresse, whose pale hue enabled the other colours to stand out. Black was obtained by red glaze with manganese oxide and lead oxide; green by white clay and lead oxide; red from natural ochres as well as alquifoux mixed with oxide of hot lead; blue by white clay and cobalt oxide.

Dangar talked continuously in her letters about establishing her own pottery at Moly-Sabata but she did not manage this until after the war in 1947. The pottery studio was eventually built in what had been the stables in the forecourt of Moly-Sabata and the kiln was built next to the wall that encloses the garden, right next to the entrance gates. The pottery is still there today with the kick wheel used by Dangar and the wedging block decorated with tiles made by her and inscribed with a verse from The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayam.

Dangar wrote on 11 October 1950 that her kiln had been blessed by the ‘curé’ (priest). She had risen at 5am to supervise the fire and that at that hour of the morning she felt blessed to have the support of ‘le Seigneur’ (God). She said that she was proud to bring these terracotta pots into the world like children and added particularly so since they were also born in a stable. She also wrote of the difficulties that attended her trade and the high cost of materials as itemised by her:

Costs for January 1950, 500 logs costing 25 Fr. each one, 50 kilos of glaze at 220 Fr. a kilo (with transport on top of that), kiln rests (100 rails 2 cazettes [saggers], 25 pillars), A ton of prepared clay with transport added Taxes

Considering all the costs, the results of each firing were highly unpredictable. For instance, at the time of writing the list above she retrieved 20 large platters from the kiln but only seven were good enough to be sold and only one that was of a sufficient standard to send to the Museum at Faenza, Italy. [12]

Anne Dangar was successful in her mission, she lived the life of a true artist and she influenced all who knew her. Despite having to labour under primitive conditions Dangar left a legacy of astoundingly moving pottery and through her letters she has left us the testimony of a remarkable individual. Anne Dangar died two months after her final letter to Grace Crowley, on 4 September 1951, and was buried on the hilltop of Serrières that overlooks the Rhône river and Moly-Sabata. The entire population of Sablons-Serrières accompanied her body up the winding path to the cemetery. After her death Anne Dangar’s works were hidden from view in private collections and in the collection of Juliette Gleizes, Albert Gleizes’s widow. Five decades on, the exhibition at the National Gallery Anne Dangar at Moly-Sabata: Tradition and Innovation is the first solo exhibition of her work.

Helen Topliss