Australian Photography 1978–1988

20 Feb 1988 – 15 May 1988

Effy Alexakis, 25th March: Athens, 1985. Sydney, 1984, 1984 and 1985, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, KODAK (Australasia) PTY LTD Fund 1988.

About

Photography is an important facet of contemporary Australian art. This exhibition explored a number of ideas and associated techniques used by photographers in this country from 1978–1988. The Australian National Gallery has been fortunate in acquiring a strong collection of works from this period, partially through funding received from the Philip Morris Arts Grant and KODAK (Australasia) PTY LTD.

Exhibition Pamphlet Essay

During the 1970s and 1980s Australian artists have explored a wide range of subjects. In doing so, they have extended the parameters of photography and, in some cases, called into question the very nature of photographic representation. Their works have often been inspired by an interest in popular culture and philosophical and theoretical writings, which are not automatically associated with contemporary visual art.

The personal viewpoint has political significance in the photographs of Jillian Gibb, Helen Grace, Micky Allan and Ruth Maddison. Their works in the exhibition were produced during the late 1970s, and all present issues in series of images which are documentary in style. Each series is a narrative that highlights a specific and traditional female role in society. Jillian Gibb and Ruth Maddison address marriage in quite different ways. The irony in Gibb's series of images — which show the bride and groom becoming smaller as they disappear downhill — is conveyed in her title We’ll be happy now. Rather than illustrating a decisive moment, Maddison records the process of the marriage ritual, and has taken the bride's point of view to produce an extended account of the day's events. Grace's series Christmas dinner is also concerned with process and ritual, particularly as performed by women in their preparations for the Christmas celebration. Yooralla at twenty past three by Micky Allan is a time sequence that depicts the simple scene of a mother and handicapped child outside a school. The gentle nature of the image is enhanced by the incorporation of subtle hand-colouring.

By the 1980s, some artists were using the documentary tradition to examine European cultures in Australia. Family snapshots are the basis for Elizabeth Gertsakis’s series Innocent Reading for Origin. By arranging images of her family alongside texts that not only denote her relationship to the subjects but also refer to the gradual alienation of immigrants from their traditional cultures, Gertsakis combines an awareness of her own Greek heritage with a more universal issue. Effy Alexakis also addresses her Greek origins by exploring the assimilation and perpetuation of the Greek culture in Australia. In Greek flag, Sydney, the flag flies above the Sydney Harbour Bridge and Opera House. Alexakis also juxtaposes scenes in Green with scenes of Greeks living in Australia. Angela Lynkushka’s portraits from her series The family in Australia investigate the diverse ethnic groups in just on suburb of Melbourne.

Sandy Edwards’s portraits capture a number of characters at the Yass Show, in New South Wales. Annual country shows have always given locals the opportunity to display their talents or be judged on the quality of their livestock and produce; Merryle Johnson has photographed some of these traditional competitions as a panorama of events. A concern with similar events is evident in Grace Cochrane’s Pets’ Day 1950, in which the central scene is a pets’ parade at the artist’s old primary school. By including snapshots and childlike writing, and using soft, warm handcolouring, the artist has intended to evoke childhood memories.

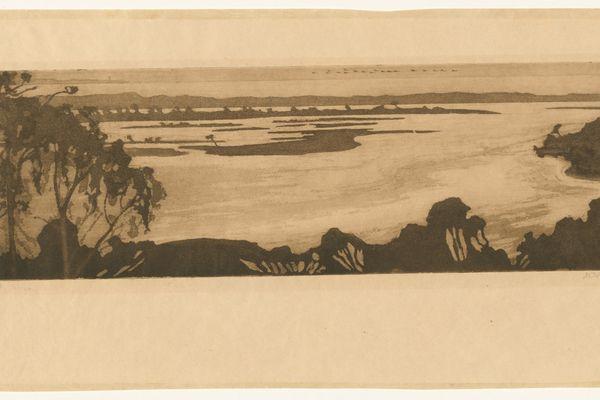

The ability of photography to challenge our perception of the everyday is evident in Christine Cornish’s elusive images, taken in the suburbs of Sydney. Grant Mudford has photographed transport containers from such a close view that colours and surfaces have become isolated and independent from the subject they describe. Debra Phillips’s diptych offers two slightly different viewpoints of a single scene. Jindabyne by Les Walkling celebrates both the beauty of landscape and the detail and quality of the photographic image. Fire and lighthouse, Cape Tourville, Tasmania, by David Stephenson illustrates human scale in the landscape; a reminder of the nineteenth-century photographic aesthetic in which human presence in the landscape was seen as proof of a capacity to explore and tame the wilderness.

Topical socio-political themes are addressed in Gerrit Fokkema's photo essay of the outback town Wilcannia and Wesley Stacey's images of 'Koorie mates', both of which highlight the affinity of Aboriginal youths with their environment. Sheila Dermoudy addresses the political issues that affect the Northern Territory. Her eerie infra-red photography is exemplified in Warship visit, in which the ship's crew appear to be in a glow of radiation. Fimo's Nguyen Descartes is a re-enactment of a well-publicized press photograph of a Viet Cong soldier being shot by the Police Chief of South Vietnam. In his image however, Fimo has restaged the incident and has used a Coke can — a symbol of Western/American culture — to replace the gun.

The most apparent characteristic of photography in the 1980s is its subjectivity. Sources for images have usually been found close at hand, with artists often photographing themselves, their friends, or aspects of their environment. Janina Green's Anxiety series was taken from photographic reproductions in a 1950s magazine. The photographs illustrated the play Breadline, which was based on Käthe Kollwitz's (1867-1945) drawings of the bread riots during the 1897-98 German weavers' strike. Green has isolated individual actresses and concentrated on their facial expressions. Fiona MacDonald uses modern stereotypes from television in her photographs of static, emotionless models who adopt simple, familiar poses. Sol Wiener's disturbing portraits depict disembodied and ethereal faces that betray a quest for identity and direction. Mark Kimber's couples are friends and relatives who pose outside their own homes. He creates a strange perspective by photographing from slightly below his subjects, and uses the changing colour of evening light to make his visual impact.

Rozalind Drummond portrays an impassive, statue-like Venus, dressed in classical costume, as the epitome of feminine beauty. The subjects in Grant Matthews's fashion series Suburban girl and in Tony Nott’s Spanner and Case also take on studied poses. Taken at night under artificial light, Nott’s panoramic images have a theatrical mood which is enhanced by their rich surface and lush colours. However, although his objects resemble those in glossy advertisements, they seem to caricature the contrived glamour of such media. Some artists create photographs that have the appearance of film stills, and they often present a sequence of these images to sustain the concept. The saturated colour and disorienting space of Suzi Coyle’s Imaging series convey a sense of arrested television action.

Dennis Del Favero gives his subjects specific identities – Laura, an Italian anti-nuclear activist, and David, an American navy pilot – and builds a scenario around their relationship. In contrast, Bill Henson celebrates the anonymity of his subjects. He presents a sea of faces, occasionally offering a glimpse of an intimate exchange. Private fantasy is the subject of Robyn Stacey’s photographs. She constructs exotic environments within the studio to reflect the nature and personality of the people being photographed, and then hand-colours and rephotographs each work to maxmize the decorative and surreal qualities of each scene. The photographs of Warren Breninger are characterized by his manipulation of both the negative and final work. The photographic detail and tone of Portrait of my daughter are relevant only as a base on which the artist has drawn and painted. Breninger chose flame-like reds and oranges to surround his daughter, who seems to be emerging from the birth canal or engulfed in a spiritual flame. Anne Ferran has also included her daughter amongst the models for her series Carnal knowledge, which deals with transgression and adolescent sexual knowledge. Through the superimposition of another negative over each original image, the artist has turned flesh to stone. The young girls lie sleeping, and in this oblivious and innocent state are able to remain self-possessed and indestructible.

The original negatives for Jacky’s Redgate’s series A portrait chronicle of photographs, Photographer Unknown, England 1953–62 were reprinted by Redgate to construct a narrative. The anonymity of the original photographer is the crux of the series; we are looking through eyes that were familiar to these subjects, yet are totally unknown to us. Redgate’s concern is in representation. By using such personal documents and choosing to enlarge them for exhibition, she has changed private scenes into public statements. Like the work of many other contemporary photographers, the series questions the importance of authorship and originality, and challenges the conventional value placed on different forms of visual imagery in our culture — a valuation that determines whether an image is appropriate for a family album or a public gallery.

The plurality of these images and the inventiveness of the techniques they employ demonstrate the vitality of the photographic medium, and proclaim its place within contemporary Australian art.