British Season: Joe Tilson and R.B. Kitaj

A Change of He(art)

19 Dec 1987 – 13 Mar 1988

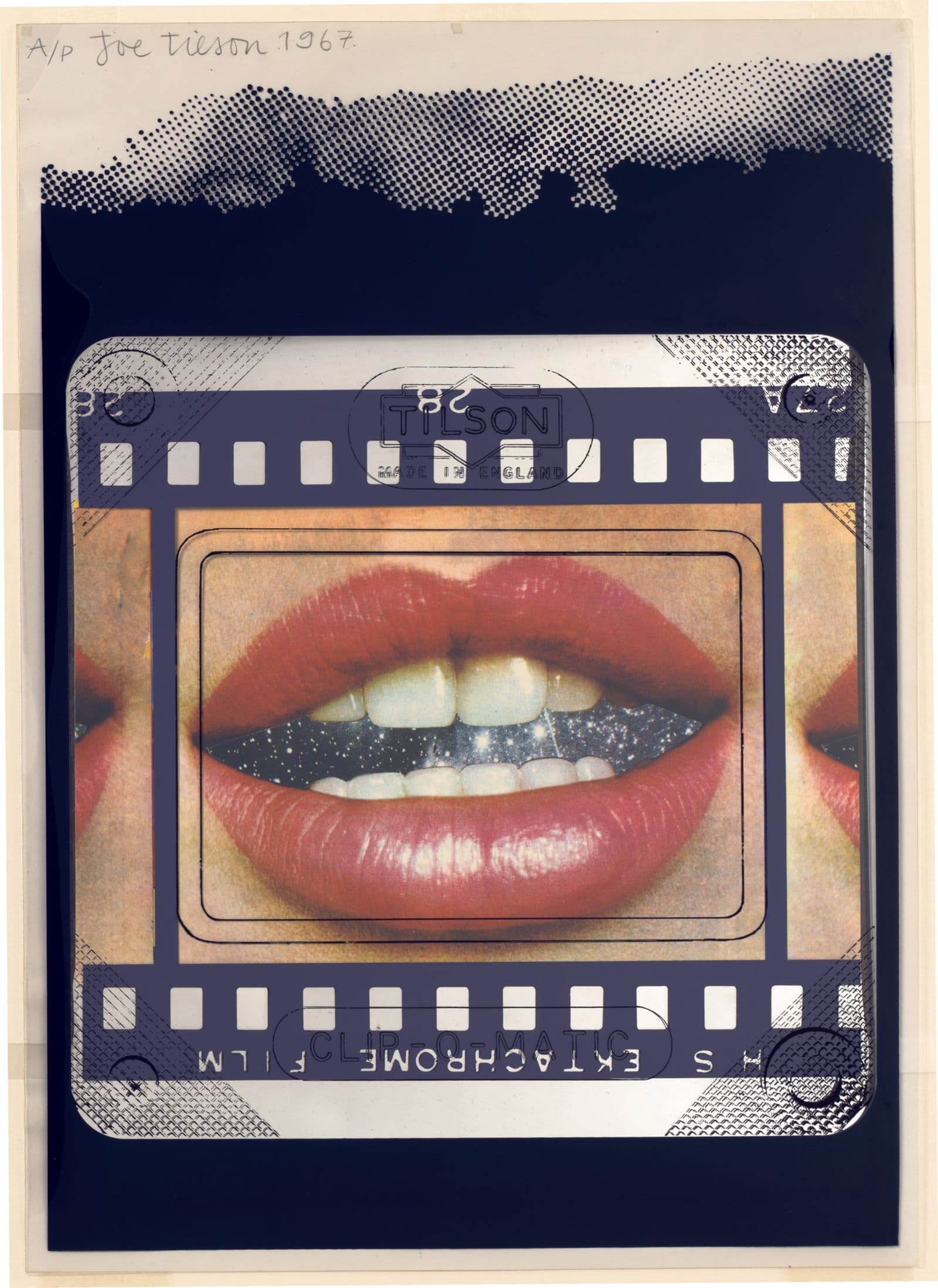

Joe Tilson, Transparency, Clip-O-Matic Lips, 1967, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1978 © Joe Tilson. DACS/Copyright Agency

About

Joe Tilson and R.B. Kitaj are the first artists to be featured in a season of British graphic art—the term 'British' being used somewhat flexibly in the case of Kitaj who, although born in the United States, received the greater part of his art education in England and has lived there for most of his working life.

Although both Tilson and Kitaj made a few prints as students, they came to serious printmaking in the early 1960s after being invited to work in London with the screenprinter Chris Prater of Kelpra Studio. Tilson made images reminiscent of works by some of his American contemporaries, presenting aggrandized decals, mouths eyes and ziggurats as single icons. Kitaj, often esoterically allusive, made collages that were part abstract and part photographic, in which, as he put it, he was 'doing Cézanne again after Surrealism'. Both incurred the wrath of traditional printmakers who rejected the use of photography in ‘original’ prints.

Although superficially Tilson and Kitaj may appear to have little in common, in fact their works display many underlying similarities. Both grew to a greater awareness of symbolism as users of the London library assembled by Aby Warburg which helped transform Renaissance scholarship. Both have maintained close relationships with living poets and have read intensively — their fascination for words as images revealing itself in forms ranging from abstract textual collage to mantras or concrete poems. In Tilson's case, this interest in language is coupled with an awareness of semiology, the study of which analyses society's use of various sign systems, from tattoos to advertising.

Considerable changes took place in the work of both artists as the technological optimism of the 1960s gave way to the more reflective 1970s. Tilson's ideas were modified by debates about nuclear power, by dissension concerning the war in Vietnam and by a new awareness of the effects of consumerism on the earth's resources, a concern heightened by the first photographs of our planet taken from the moon. These experiences not only affected the kind of art he produced, but dramatically changed his way of life.

Kitaj, who had been a student at the Royal College of Art in London when the long tradition of drawing from the model was being questioned and to some extent rejected, formulated a group exhibition marking a return to the depiction of the human figure and arguing for traditional values; in his own work, he gave up photo-collage in printmaking for directly drawn lithographs and etchings.

Tilson abandoned screenprinting on plastics and metallic surfaces in favour of individual handmade papers and took up soft ground etching, a technique more responsive to touch. Leaving his urban and political existence in London and moving to the country, he turned to art based on first-hand experience rather than on second-hand imagery culled from the media, although since the early 1970s he has cross-referenced in his work the symbols by means of which people throughout the ages have expressed their relationship to nature. The beautiful concrete poem based on the repetition of the word 'earth', which contains the words 'hearth', 'heart' and 'art', sums up the artist's most recent preoccupations.

Pat Gilmour

The content on this page has been sourced from: Kinsman, Jane., Cathy Leahy, and Pat Gilmour. British Season Joe Tilson and R.B. Kitaj : A Change of He(Art). Canberra: Australian National Gallery, 1987.

Joe Tilson

Born in London in 1928, Joe Tilson was one of the generation of artists that graduated from the Royal College of Art in the mid-1950s. He had already decided to become an artist at the age of eight, but it was not until after the war that he received any formal art training. In 1949, having served three years in the British air force, he enrolled at St Martin’s School of Art and in 1952 undertook post-graduate study at the Royal College.

During this period Tilson made a few prints, but it was not until he executed his first screenprint, Lufbery and Rickenbacker, in 1963, that he really became involved in printmaking. From that time on, prints have been an important part of his work, and he stresses that they are in no way secondary to his constructions and paintings.

Tilson perceives his output as totally integrated and in fact has deliberately sought to erode the distinctions between different media. His attempts to extend the parameters of printmaking have led him to contravene accepted definitions of what a print should be, and in the early 1960s he compiled a list of 'unacceptable' practices – such as tearing the work, making it from plastic, collaging objects to its surface etc. In the ensuing decade he implemented most of these ideas, as for example in the Sky series in which he attached plastic objects and pieces of torn paper to the surface of the prints.

Throughout the 1960s Tilson shared in the general optimism concerning technological progress, and this led him to introduce materials that had never before been used in printmaking. He worked with vacuum-formed plastics and, as in Transparency, clip-o-matic lips, 1967, printed on synthetic polymer film and metallized acetates. The majority of his prints from the mid-1960s featured photographic imagery and themes drawn from the mass media and the world of consumerism, and a number of works were inspired by throwaway objects such as the postcards, decals and matchbooks that the artist picked up on a trip to New York in 1965. From these ephemeral items, Tilson constructed such monumental pieces as PC from NYC, 1965, a two-metre-high, fold-out postcard-print. In Transparency, clip-o-matic lips, he created an unforgettable image from what was originally an advertisement for toothpaste. By celebrating these ephemeral, commonplace objects and sources, the artist invites the viewer to reappraise their role in our daily environment.

The late 1960s saw Tilson pursuing his fascination with the ‘dream world’ created by the media, and with the techniques used in its presentation. This theme was explored in two important projects of 1969-70: the Pages series and the portfolio A-Z box ... fragments of an oneiric alphabet ... In the A-Z box, Tilson emulates both glossy magazines with their evocative imagery and high-finish, and newspapers with their coarse half-tone dots and collage of information. The sequence of prints in the portfolio becomes increasingly dreamlike, with its bizarre juxtaposition of advertising photographs, movie stills, and images of political figures and heroes. The Pages – both prints and constructions — utilize the newspaper-page format, investigating the ways in which information is both transmitted to, and processed by, the reader In the last years of the decade Tilson also executed prints that celebrated political figures such as the Vietnamese nationalist Ho Chi Minh and the Cuban revolutionary Che Guevara, as well as personal heroes such as the French poet Guillaume Apollinaire.

A momentous change took place in Tilson's art in the early 1970s, a consequence of his rejection of urban life. In 1972, increasingly dissatisfied with his London existence and no longer optimistic about the role of technology, he moved into the country with his family. There he adopted an alternative lifestyle, and the themes that had previously informed his prints – technology, the mass media and politics – gave way to imagery inspired by personal contact with nature.

This is evident in Alchera, a major project which Tilson began in 1970 and which was to span some four years. Originally titled Alcheringa (a term derived from the Aboriginal Dreamtime), this important group of works incorporated prints, writings, objects, sculptures and paintings. Tilson's contemplation of the four elements — earth, air, water and fire – provided the initial inspiration for the project, which developed into an investigation of the ways in which different cultures make sense of the universe and of their existence within it.

Two further themes have emerged in the artist's printmaking from the mid-1970s. In a number of works executed between 1976 and 1980, as for example in Earth mantra, 1977, he created visual mantras, using the repetition of one word or image to induce the viewer to meditate upon a particular idea. The second theme, which still preoccupies Tilson, derives from his interest in Greek art and mythology. Greek words and motifs appear in many of the artist's recent prints, and in works such as Festival for Persephone, 1987, he draws upon Greek myths in the celebration of the cycles of nature.

Accompanying this change in subject matter has been a related development towards a more hand-crafted aesthetic. The first Alchera prints, for example, although still utilizing photographic imagery, were printed on very individual handmade papers. Tilson selected these papers for the meaning they imparted to his works – thus Alcheringa 4, earth, 1971, was printed on tan-coloured paper. There has also been an increasing preference for hand-drawn rather than photographic imagery in Tilson's later work as, for example, in The arrival of Kore, 1982. This is related to the fact that in the mid-1970s Tilson began to favour the more autographic intaglio techniques of soft ground etching and aquatint. He even set up a small etching press in his studio so that he could work directly on his own plates. It is therefore not only in style and subject matter, but also in technique, that his prints of the past fifteen years differ markedly from those he produced in the 1960s.

Cathy Leahy

R.B. Kitaj

R.B. Kitaj was born in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1932, the son of liberal Jewish, although agnostic, parents. One of his happiest childhood memories is of attending classes at the Cleveland Museum of Art. As a young man he continued his studies in art, initially at the Cooper Union in New York and then at the Academy of Fine Art in Vienna, the city of his stepfather's family. He financed his education by working as a merchant seaman on the 'Romance Run' from the United States to Cuba, Mexico, Brazil and Argentina.

It was during his student days in New York that Kitaj discovered the bookstores of 4th Avenue: 'l had discovered pound and Eliot and Joyce and Kafka and an innate bibliomania was rekindled there as it would be, on and off, manic and depressive through my life, feeding and bloating the pictures I would do'.

After a period of conscription in the American army from 1956 to 1958, when he was stationed in Europe, Kitaj took advantage of the grants scheme for G.l.s and enrolled at the Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art at Oxford. At Oxford he came under the spell of the Renaissance scholar Professor Edgar Wind, whose lectures delved into the complex nature of Renaissance subject matter; complexity of a different kind would characterize Kitaj's own subject matter in the years to come. His first attempts at printmaking — which resulted in a small group of lithographs depicting traditional landscape and portrait themes — date from these early years in England.

In the autumn of 1959, Kitaj enrolled in postgraduate studies at the Royal College of Art in London where, older and more experienced than his fellow students, he became a prominent figure among the younger British students such as David Hockney, Patrick Caulfield and Allen Jones. The Royal College at this time was the springboard for many young artists later associated with the British Pop movement — a style which freely borrowed its forms from popular culture and used the latest technology, including photographic processes, to create art. During the early 1960s, the debate on the relative legitimacy of machine and handmade art aroused considerable feeling, and many artists were openly criticized for working with photography in this way. Kitaj and others, however, maintained that the new technologies existed in order to be used and that censure of this kind was élitist.

Kitaj's major excursion into printmaking began with his association with the printer Chris Prater at London's Kelpra Studio in 1963. It was Prater's skill in screenprinting, particularly in cutting stencils, that allowed the artist to develop a complex print style, based on collages of textures, colours, shapes and words. Attracted to the tradition of the Surrealists and to their attempts to expose the workings of the unconscious through the juxtaposition of disparate objects and ideas, Kitaj found that with Prater's assistance he could produce screenprints featuring strange thematic arrangements in visually satisfying combinations. The result was intricate, highly personal prints such as Boys and girls!, 1964. This abstract composition was inspired by the second movement of Gustav Mahler's second symphony and included photographs of the actor Werner Krauss in the anti-Semitic film Jud Suess, as well as images from a German nudist magazine of the post-war period.

Although Kitaj favoured socialist ideals, his subjects were never overtly political. Events of the recent past such as the Spanish civil war and the fight against fascism were important to him and featured as part of the screenprint series In our time: covers for a small library after the life for the most part. Using photo screenprinting for the series, Kitaj selected fifty book jackets that he had collected over the years and that he hoped would summarize some of the important events and ideals of the twentieth century. As well as featuring a Spanish Republican song book cover, he made screenprints based on covers for The Prevention of Destitution by the Fabian socialists Sidney and Beatrice Webb; the pioneering anthropological study Coming of Age in Samoa by Margaret Mead; and Leon Trotsky's The Defence of Terrorism. A passionate bibliophile, Kitaj continued to use book jackets in his screenprinted compositions after In our time was published in 1969.

By the mid-1970s, and in an apparent rejection of his earlier print style, Kitaj turned his back on collage compositions. He had come to view collage as 'banal' — as the wayward step of a young artist exposed to too much freedom and caught up in the fashion of abstraction: 'At a tender age, someone like me would think if Eliot could append notes to The Wasteland and Dadaists glued god knows what onto their pictures, then I could paste on quasi-scholarly notes onto my pictures'.

In 1976, in an attempt to redress this imbalance, Kitaj organized The Human Clay, an important exhibition celebrating figure drawing in the work of contemporary artists. This was the way 'forward' for Kitaj, who saw himself becoming part of the great figurative tradition. The 'political act' of adopting a less esoteric style would, he believed, make his work more accessible, by providing artistic references which could be readily understood.

As enthusiasm for the new technologies of the 1960s — many of which had become prohibitively expensive — gave way in the mid-1970s to a more tempered view about the merits of these 'advances', Kitaj turned to more traditional printing processes.

The technique of lithography, whereby the artist uses a greasy crayon to draw directly onto a stone or plate, was eminently compatible with his new interest in drawing the human figure.

Etching, too, proved appropriate to his more intimate, 'confessional' subjects. From 1982 to 1983 Kitaj lived in Paris, where he worked with Picasso's principal intaglio printer, Aldo Crommelynck. For a year he visited Crommelynck's printing house each week in order to further his etching technique. The delicate hand-drawn lines of this process were ideally suited to his small self-portraits and traditional landscapes, as well as to subjects such as his own family life and sense of Jewishness — all of which are recent themes of his prints.

Jane Kinsman

///national-gallery-of-australia/media/dd/images/R_B_Kitaj_22500.jpg)