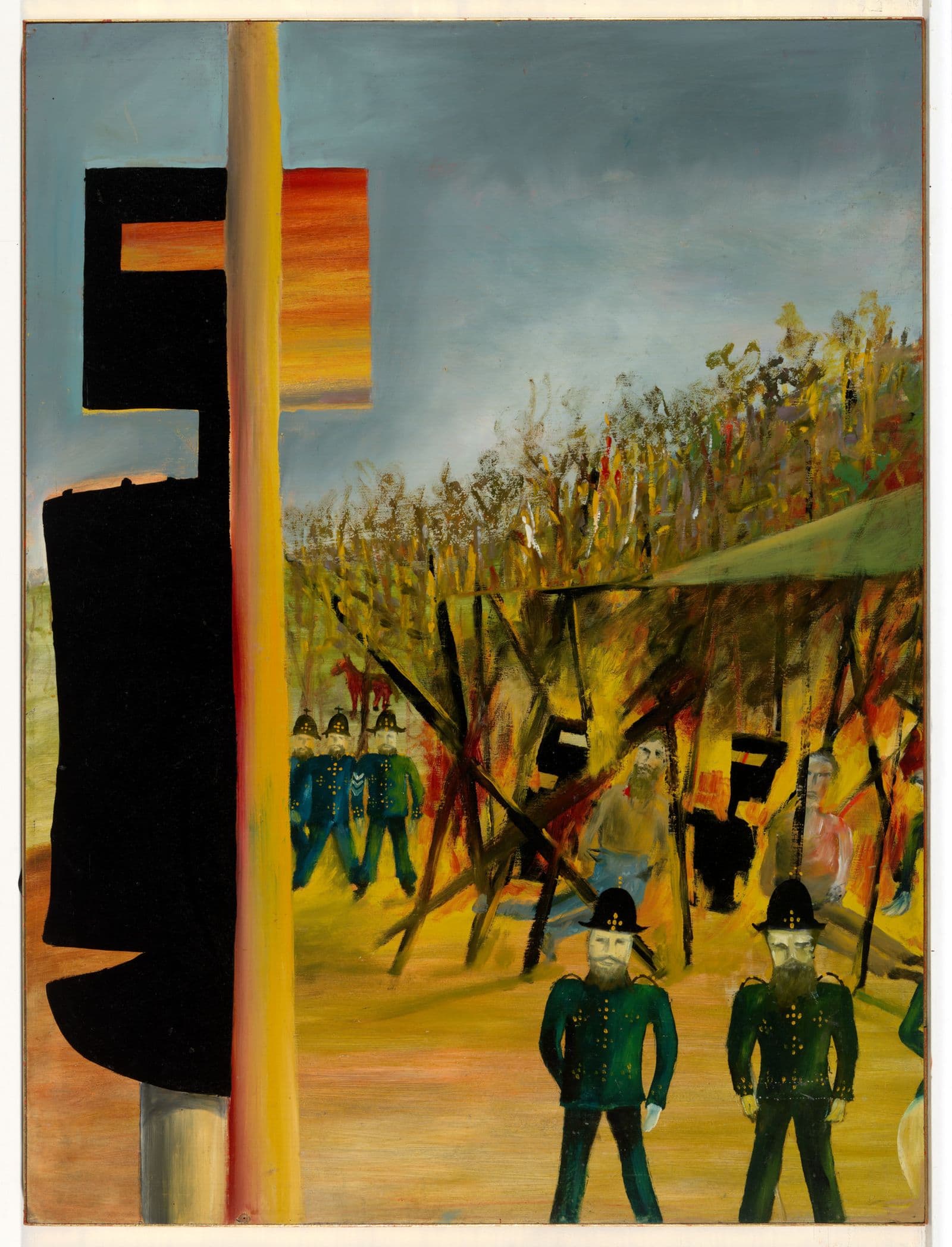

Burning at Glenrowan by Sidney Nolan

22 Feb – 20 Apr 1992

Sidney Nolan, Burning at Glenrowan, 1946, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, Gift of Sunday Reed 1977.

Exhibition Pamphlet Essay

‘I find that a desire to paint the landscape involves a wish to hear more of the stories that take place within the landscape. Stories which may not only be heard in country towns and read in the journals of explorers, but which also persist in the memory, to find expression in such household sayings as ‘game as Ned Kelly’. From being interested in these stories it is a simple enough step to find that it is possible to combine two desires: to paint and to tell stories.

The history of Ned Kelly possesses many advantages from this point of view. Most of us have heard of it, in one way or another, during our childhood, and it is still a topic of conversation in those parts of Victoria where the Kelly family lives.

In its own way it can perhaps be called one of our Australian myths. It is a story arising out of the bush and ending in the bush.

Whether or not the painting of such a story demands any comment on good and evil I do not know. There are doubtless as many good policemen as there are good bushrangers.’

Nolan's decision to use the Kellys as a theme was reinforoed by a number of experiences:

As a young child he visited Melbourne's Aquarium, where he saw the unusual combination of fish in green water, a Cobb and Co. coach and Kelly’s amour, which were then displayed there. He recalled that 'it all looked naturally in place'.

His grandfather, William Nolan, once a sergeant during the pursuit of the Kellys at Beechworth, told his grandson how the police did their best to avoid any encounters. He also spoke of the rumours, often false, that were spread by the local inhabitants about the Kellys, and mentioned that blacktrackers were not used, though Kelly feared their expertise in the bush.

Nolan read J. J. Kenneally's The Complete Inner History of the Kelly Gang and Their Pursuers, first published in Victoria in 1929, and also the Report of the Royal Commission on the Police Force in Victoria, issued in 1881. Some passages that Nolan read in both these publications became the themes of individual paintings, and these accompanied each entry in the catalogue of the first exhibition in 1948. Subsequent catalogues followed this practice, using passages like these:

Burning at Glenrowan. 1946

Very Rev. Dean Gibney: 'l got no answer, of course, and I looked in and found the bodies of Dan Kelly and Steve Hart lying together. As far as I could tell they were burnt from the waist up'.

Siege at Glenrowan. 1946

At about eight o'clock in the morning a heart-rending wail of grief ascended from the hotel. The voice was easily distinguished as that of Mrs Jones, the landlady. Mrs Jones was lamenting the fate of her son, who had been shot in the back by police, as she supposed fatally. She came out of the hotel crying bitterly and wandered into the bush on several occasions, etc.

On Burning at Glenrowan and Siege at Glenrowan Sidney Nolan says:

These [paintings] were once joined together and I had Mrs Reardon and her baby still fleeing for their lives. It was once six feet [1830 cms] by four [1220 cms], but late one night, Jack Bellew, a journalist, said, 'Look Sid, that painting is too bloody big, cut it in two'. I told him to leave it alone, but to prove it was not too big I would cut it in two. You see I come from a long line of Irishmen. So I cut it and looked at them separated and together, and they looked better together. Unfortunately I had patted them forever.

The Kelly paintings contain oblique references to Nolan's own life. As his life changed, so the Kelly of the paintings changed from an unassailable and defiant hero, to the dejected, forlorn and rather frightened outlaw who appears in later paintings. Nolan said, 'As in the early paintings I used him as a shorthand for my own emotional state'.

With this series, Nolan explores the role of myth in art, and the symbolic forms of Kelly's helmet and armour became important devices to focus the viewer's attention. Nolan was aware of the black square that 'had been floating around in modem art for some time', and that had been used by international artists like Malevich and Moholy-Nagy. 'All I did was put a neck on the square', he said. The helmet and its pictorial use was the modern device in the series, and its imposition on his lyrical landscapes created a difficult visual problem for Nolan.

The helmet casts gloom and, by exposing his eyes, the aperture reveals Kelly's moods. The eye-slit in the helmet — lifting the earth up to the sky or, as in Burning at Glenrowan, showing the fire burning behind the eyes — suggests alternative views of the landscape.

The Kelly paintings and the drawings of around the same time do not have the usual relationship of preparatory sketch to finished composition. None of the Kelly drawings in the National Collection could be considered studies in the ordinary sense of the word. This is definitely the case for the two displayed in this exhibition, Kelly, tree and trooper and Kelly at Glenrowan. Nolan's approach to the Kelly paintings was substantially different to the way he dealt with the drawings, demonstrating that he attacked the paintings afresh. The series of Kelly drawings, produced in a flash of feverish inspiration in the course of no more than a few hours, seems, nonetheless, to have been important in the process of Nolan's thought about the paintings. The division of the picture plane and the placement of characters are two compositional elements that are addressed in these and subsequent sketches. Nolan produced some sketches after the paintings were completed, as if he was recalling both the Kelly history and the process of painting, and comparing the actual hero and his own interpretation of the legend.

The series of drawings of bushranger heads, which Nolan made in January 1947, also appears to have been produced in a short period and, like the 1946 series, has a life independent of the Kelly paintings. The colourfully kerchiefed faces, another device used to identify bushrangers, invoke many outlaws and not necessarily the Kelly gang.

Nolan has frequently returned to the Kelly theme since 1947 and recently said:

‘I don't know what to say if people say I paint Kelly because that's all I can do, because it's like saying Giotto used Biblical scenes because he hadn’t read the Koran . . . it wasn't part of his culture.’

I'd like to think that the day before I died I'd paint a good Ned Kelly painting.

During the siege at Glenrowan, a group of press reporters arrived there on a special train from Melbourne. Although their accounts of the siege varied or, as some believe, were biased against the Kelly gang, their observations are exciting to read.

The following extracts are from the Melbourne Australasian Sketcher 102, vol. viii, Saturday 17 July 1880. This was the last issue in a series titled 'Destruction of the Kelly Gang'.

The Personal Narrative of One who went in the Special Train

… and now occurred the most sensational event of the day. We were watching the attack from the rear of the station at the west end, when suddenly we noticed one or two of the men on the extreme right, with their backs turned to the hotel, firing at something in the bush. Presently we noticed a very tall figure in white stalking slowly in the direction of the hotel. There was no head visible, in the dim light of morning, with the steam rising from the ground, it looked, for all the world, like the ghost of Hamlet's father with no head, only a very long, thick neck. Those who were standing with me did not see it for some time, and I was too intent on watching its movements to point it out to others. The figure continued gradually to advance, stopping every now and then, and moving what looked like its headless neck slowly and mechanically round, and then raising one foot on to a log, and aiming and firing a revolver. Shot after shot was fired at it, but without effect, the figure generally replying by tapping the butt end of its revolver against its neck, the blows ringing out with the cleanness and distinctness of a bell in the morning air. It was the most extraordinary sight I ever saw or After Ned Kelly had been read of in my life, and I felt fairly spell-bound with wonder, and I could not stir or speak. Presently the figure moved towards a dip in the ground near to some white dead timber, and, more men coming up, the firing got warmer. Still the figure kept erect, tapping its neck and was seen to wave from the using its weapon on its assailants. At this moment I noticed a man in a small round tweed hat stealing up on the left of the figure, and when within about 30 paces of it firing low two shots in quick succession. The figure staggered and reeled like a drunken man, and in a few moments afterwards fell near the dead timber. The spell broken, and we all rushed forward to see who and what our ghostly antagonist was. Quicker than I can write it we were upon him; the iron mask was tom off, and there, in the broad light of day, were the features of the veritable bloodthirsty Ned Kelly himself.

After Ned Kelly had been captured, a doctor from Benalla attended to his wounds.

The following extracts relate to the burning of the Jones' Hotel at Glenrowan.

Instantly a white handkerchief was seen to wave from the doorway, and at the same moment some 25 persons rushed out towards the police line with their hands held high up above their heads. They rushed towards us, crying out in piteous accents, 'Don't fire! For God's sake don't shoot us; don't, pray, don't!' They were here ordered to lie down, which they obeyed at once, all falling flat on their stomachs, with their hands still in the air. It was a remarkable scene, and the faces of the poor fellows were blanched with fear, and some of them looked as if they were out of their minds. The police passed them one by one, in case any of the outlaws should be amongst the crowd. They handcuffed two young fellows named McAuliffe, known as active sympathisers with the outlaws, and the rest were set free. The 10 minutes grace being up, the police commenced to rake the hotel, in which I joined. From east, west, north, and south we poured in volley after volley, and yet no sign of surrender. We learned from those who left the house that Byrne was dead; that he had died leaning over a bag of flour, reaching for a bottle of whisky at the bar; that a ball had struck him in the abdomen, and that the blood spurted out like a fountain; and that he fell dead without a groan. We also heard that Dan Kelly and Hart were standing side by side in the passage between the two huts, looking cowed and dispirited, without the slightest sign of fight left in them. In fact, as one informant said, they looked for all the world like two condemned criminals on the drop, waiting for the bolt to be drawn'.

At a quarter to 3 o'clock a sharp rattle of rifles was heard, and a man was seen advancing from the west end of the house with a large pile of straw, which he placed against the weatherboards and lighted. The flames quickly ran up the side of the house and caught the canvas ceiling. In about 10 minutes the whole of the roof was in a blaze. Just at this moment a priest was seen going up quickly to the front of the house. The crowd closed in after him, and in a few moments the door was burst open. Four men rushed in, and soon reappeared, dragging out the body of Byrne, who still wore his breastplate ... In the meantime, the unfortunate man Cherry, who was wounded to death, was drawn out at the back of the house, and the priest anointed him, and in a few moments after he calmly passed away. The bodies of Dan Kelly and Hart could now be plainly seen amongst the flames, lying nearly at right angles to each other, their arms drawn up and their knees bent, and I feel perfectly certain that they were dead long before the house was fired. Mrs. Skillian and Kate Kelly stood at the railway gates watching the inn burning, and when the charred remains of their brother were brought out, howled loudly and lustily over the blackened bones.

Touring Dates and Venues

1991–1992

- City of Ballarat Fine Art Gallery, VIC

27 August 1991 – 6 October 1991 - Benalla Art Gallery, VIC

12 October 1991 – 10 November 1991 - Orange Regional Gallery, NSW

16 November 1991 – 26 January 1992