Colour + Concept

International Colour Photography

7 Sep 2002 – 1 Dec 2002

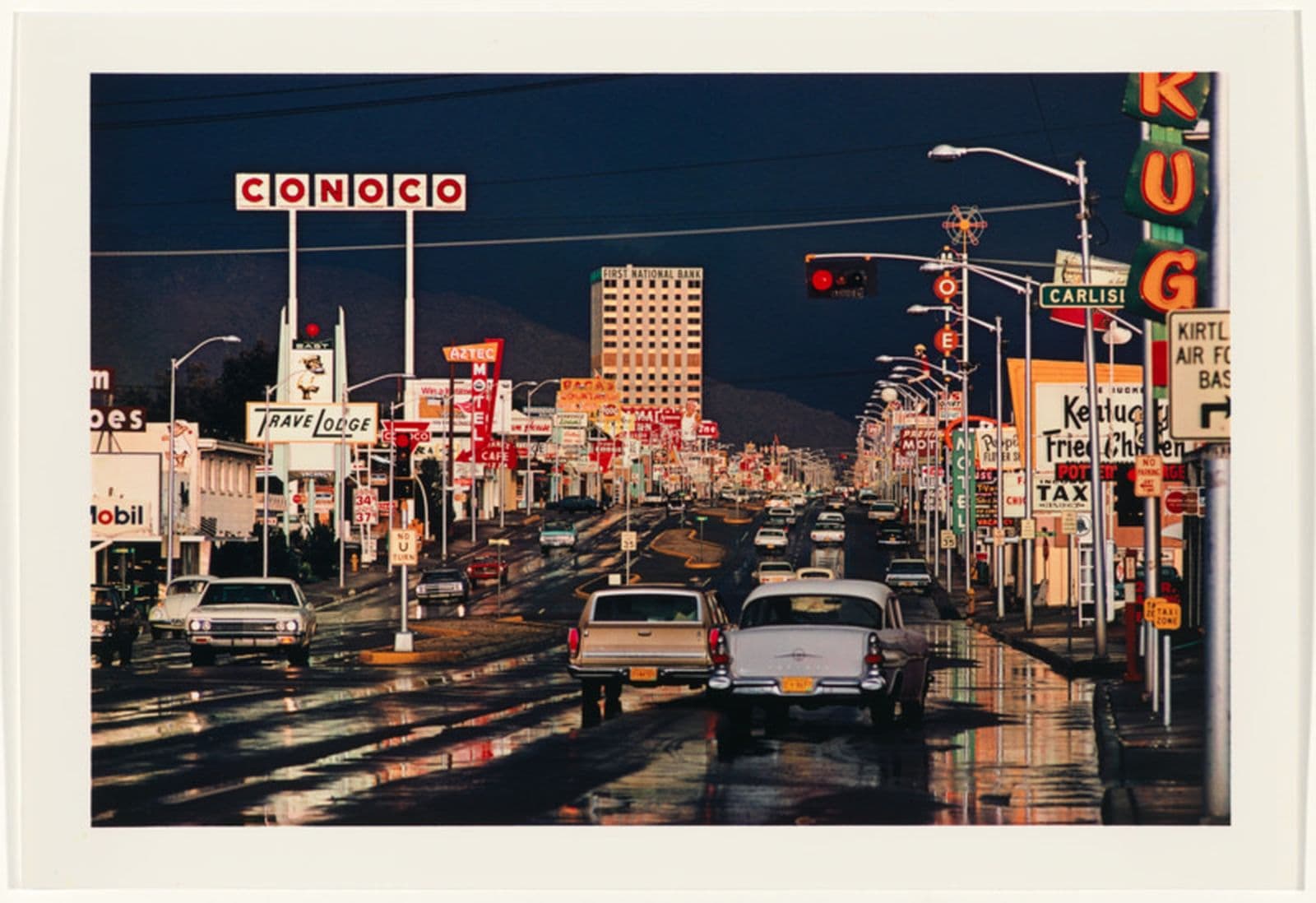

Ernst Haas, Albuquerque, New Mexico, 1969, purchased 2000

About

Colour + Concept was mounted to coincide with the National Gallery of Australia’s 20th birthday celebrations and presents the work of 20 photographers who explore abstract or conceptual themes in their work and who might be described as ‘colourists’ for the passion they have for colour work. Several photographers in the exhibition, such as Ernst Haas, are recognised as innovators in the field, many trained as painters before turning to photography, and some—Saul Leiter and Sean Scully—work in both mediums. A number of the photographers in the exhibition create worlds of a heightened reality beyond everyday appearances and others demonstrate the duality of their medium which, on one hand can be relentlessly descriptive, and on the other can express complex philosophical or spiritual values.

The exhibition drew on the Gallery’s extensive holdings of over 400 colour photographs, in particular acquisitions from the 1980s and from the past five years; both are periods when an increased representation of significant colour photographers was sought for the collection. The works date from the mid-1930s to the present, however, the focus of the exhibition is on the last 30 years when the affordability of colour materials and improved ease of production opened the medium to a broader range of photographers.

curatorial Essay

Until the 60s, colour was complicated and expensive to develop and print and also reproduce in magazines or books. The finest colour processes were largely the province of the top commercial photographers and were primarily employed in advertising and fashion. From the 30s to the 50s, advertising photographers in America in particular, such as Anton Bruehl, became masters of sophisticated, elaborately lit, meticulously composed studio colour photography.1 Nearly 200 of Bruehl’s colour photographs appeared in Vogue between 1932 and 1934. Colour became aligned closely with consumerism.

Due to the slow speed of colour films before the 60s and the unpredictability of natural lighting, action shots were rare. Therefore few photographers took their cameras in to the streets to capture action. As a result, the first generations of colour photographers are associated with studio photography and high artifice rather than spontaneity and the everyday.

The view in popular culture that colour represented fantasy was affirmed in 1939 in the pioneering colour film The Wizard of Oz, in which Dorothy and her faithful pet, Toto, escaped the monochrome reality of Kansas and literally burst into the hyper-real Technicolor dream world of Oz. Although the Land of Oz was beautiful it was also deceptive. The wizard turned out to be a charlatan who relied on cheap tricks to evoke wonder and mystery. The film proposed that colour equates with the unsettling world of the imagination and that such realms are good places to visit (like the cinema) but not to live in.

Black and white photography has dominated the critical histories of fine art photography. In the mid-20th century photographers found the results of shooting in colour unpredictable. Critic Max Kozloff noted that early Kodachrome (the first colour process widely available to the public) would show ‘a scarlet bathing suit wearing the woman instead of the other way around,’ meaning that the dominant form in a composition in black and white will not necessarily dominate a colour image.2 Photographers had to learn how to think in colour.

In the same way that coloured fantasies featured in films during the darkest days of the Depression, some photographers also looked to colour to lighten the social mood. Photo-journalists Ernst Haas and Saul Leiter took their cameras into the streets. Haas in particular is acclaimed for his pioneering techniques, such as panning with the camera, which overcame the limitations of slow films and created action shots.

Born in Austria, Haas witnessed the horrors of war directly. For him the post-war years were bleak and made him desire colour: ‘I was longing for it, needed it, I was ready for it. I wanted to celebrate in colour the new times, filled with new hope.’3 As early as 1953, just two years after he had migrated to America, Life published his seminal colour photo essay on New York. ‘Images of a Magic City’ ran to 24 pages over two issues and to that date was the longest colour story that the magazine had ever carried. Reflections – Third Avenue from the photo essay is an unmanipulated photograph made abstract by the unusual choice of angle. For Haas, America was something to be celebrated and his adopted city appears mysterious, dynamic and organic.

Saul Leiter, who worked in fashion advertising in New York in the 50s, has said that colour was as much the subject of his photographs as any other component.4 Leiter exploited the subdued palette of the available colour films, using the painterly, delicate and sometimes murky quality to great advantage. His photographs are structured with immaculate care, resulting in richly layered compositions. In Leiter’s work the world is often approached obliquely—seen through windows or reflected in mirrors. Figures are either partially hidden or in shadow, sometimes his subject is looking inward as if lost in thought. The world that Leiter creates is a quiet one, contemplative and dream-like. This reverie dematerialises the subjects suggesting perhaps an influence from his spiritual beliefs. Leiter was the son of a distinguished Talmudic scholar and studied theology before moving to New York when he was 23 to pursue a career as an Abstract Expressionist painter.

Haas had a strong influence on his contemporaries and younger photo-journalists alike. Haas’s colleague at the Magnum agency, New Zealander Brian Brake (whose moody impressionistic 1960 photo essay 'Monsoon' was shot for Life magazine and the subject of a 1999 exhibition at the National Gallery) owed much to Haas’s precedent and was in turn highly influential in the early 60s.

Indian photojournalist Raghubir Singh was also influenced by these pioneering photojournalists’ use of colour. Pavement Mirror Shop, Howrah, West Bengal from 1991 is an extraordinary maze of oblique angles and reflected images. The photograph demonstrates Singh’s ability to meld the ‘decisive moment’ and the documentary traditions of photography with the formal complexity of composing in colour. Neither approach dominates the image, rather they are mutually dependent.

In general, colour was distrusted by many photojournalists. Its association with advertising was difficult for many to reconcile and they doubted its capacity to represent thought-provoking subject matter. Serious subjects seemed to demand the bluntness of black and white. American photojournalist David Douglas Duncan stated: ‘I’ve never made a combat picture in colour—ever. And I never will. It violates too many of the human decencies and the great privacy of the battlefield’.5 Not until the Vietnam War would photographers show how iconic images of war could be taken in colour. British photojournalist Larry Burrows studied the Old Masters and the paintings of Goya and these models appear in his photographs of the Vietnam War. Near Dong Ha, South Vietnam (1966) is a modern version of 19th-century history paintings, and in Hue, South Vietnam (1969), the woman mourning the death of her husband is like a Gothic pietà.

The 60s saw the widespread ownership—especially in the United States—of colour television sets, improvements in colour processes, and publishing in colour becoming economically viable. By the end of the decade magazines were full of sharp colour photographs and it had become the medium of choice for the family snapshot. So that when popular song writer Paul Simon wrote Kodachrome in 1973, colour photography was ubiquitous. He sang that they ‘give us those nice bright colors, they give us the greens of summers, makes you think all the world’s a sunny day’. For Simon ‘everything looks worse in black and white’ and he does not want to return to the dull, real world.6

The work of the New Color Photographers of the 70s and 80s—William Eggleston, Stephen Shore, Neal Slavin and Joel Meyerowitz, among others—reveals a fascination with the signifiers of modern consumer culture: street signs, neon lights, and shopping centres. Although the super-intense colour is highly seductive, there is also a feeling of urban gaudiness and isolation in many of their photographs. This sense of the photographer standing apart from his surroundings is a key element in the work of Stephen Shore. Max Kozloff wrote at the time, ‘if his art illustrates anything, it is the theme of being alone in colour, a solitary in a lavishly rendered brick, grassroots, and plastic America.’7

The New Color Photographers’ work is more carefully structured than was acknowledged at the time. Stephen Shore, for instance, divided his compositions horizontally into halves or thirds. From 1974 he used an 8 x 10 inch camera and contact printed the photographs from the negatives. Of his working method, Shore has written: ‘Outside the controlled confines of the studio, a photographer is confronted with a complex web of visual juxtapositions that realign themselves with each step. In bringing order to this situation, a photographer solves a picture, more than composes one’.8

Neal Slavin and Joel Meyerowitz both began their careers in commercial photography and, like Stephen Shore, photographs by Meyerowitz in the exhibition are taken with an 8 x 10 inch view camera. Such a camera, weighing over 20 kilos, demands a certain formality in taking a photograph, and produces a result rich in detail and nuance.

Colour photography was also employed in the 70s by a generation of conceptual artists. Many of these artists were interested in perception. Dutch artist Jan Dibbets began his career as a painter in the 1960s before adopting photography as an integral part of his minimalist assemblages. Dibbets is interested in the ways that we find it necessary to structure the world in order to understand it. Comet Horizon 6˚–72˚, sky/sea/sky (1973) reorders the Dutch landscape into an abstract formation by subtly changing the angle of the camera to the horizon in each shot. ‘I want to say something about abstraction and about the fact that abstraction can be present in a figurative image—and that this doesn’t have to look like a Mondrian’.9

American photographer John Pfahl explored similar ideas of perception and representation in images of landscapes altered by the addition of geometric lines. Pfahl’s Moonrise over pie pan, Capitol Reef National Park, Utah (1977) plays with the similarity in appearance between the moon and a mundane dish on the ground.

It seems a witty comment on Ansel Adams’s famous moonrise pictures from the 1940s–1960s.

Irish painter Sean Scully became internationally renowned for his textured and gridded abstract paintings in the 80s and 90s. In 1997, he began exhibiting photographs alongside his paintings. Art Horizon (2001) is his largest and most ambitious work in this genre.

It is made up of 10 images of enlarged close-ups of his own paintings. The title intrigues; is it suggesting that art is a world created by the artist? By mining his own abstract paintings Scully challenges the idea that art is grounded in nature or reality. Yet Scully’s art references both the real world and the world of art. Most of Scully’s photographs are of walls or doorways shot from directly in front thus eliminating any spatial perspective. His images show repairs and layers of aged paint. They are concerned with notions of decay and loss, and how we try to counter these things.

Scully speaks of his early childhood education in Catholic schools as ‘something very exotic and difficult, but rich and full of mystery’ and that there was ‘the belief in another reality, in a reality that we couldn’t see, that we could only imagine’.10

Scully’s comments could be used to describe many of the images in Colour + Concept. The photographs can be read as abstract patterns or as information. They illustrate how photography produces images which can be read on many levels simultaneously.

Anne O’Hehir

Assistant Curator of Photography, National Gallery of Australia