Crescent Moon

Islamic art and civilisation in Southeast Asia

24 Feb 2006 – 28 May 2006

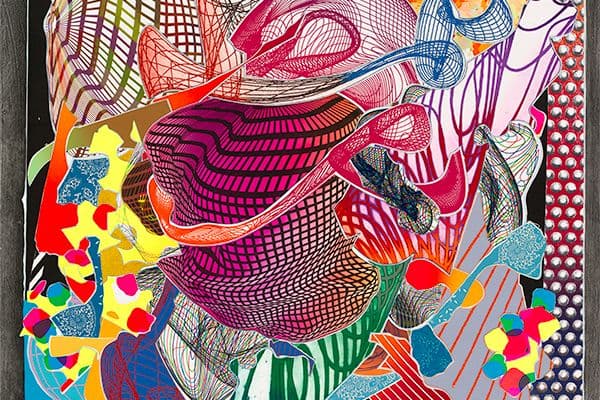

Indonesia, Aceh, Sumatra, Ceremonial hanging, early 20th century, purchased 1984

About

This celebration of the Islamic art and heritage of Australia’s nearest neighbours – Indonesia and Malaysia, and the Muslim communities of the Philippines, Thailand, Burma and Cambodia – explores the beauty and complexity of the region’s metalwork, textiles, wood carving, illuminated manuscripts, gold, lacquer, porcelain and stone.

Introduction

Crescent Moon: Islamic art and civilisation in Southeast Asia is a spectacular visual exploration of the Islamic heritage of Australia’s nearest neighbours. As the first major international exhibition to focus on the Islamic art of Southeast Asia, Crescent Moon introduces Australian audiences to the beauty and complexity of Islamic culture within our region. Southeast Asian creative genius found expression in a wide variety of media, including metalwork, manuscript illumination, textiles and wood carving.

The exhibition reveals the unique developments in the arts of Islamic Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines, as well as the Muslim communities of Thailand, Burma, Cambodia and Vietnam. Splendid objects in silk, gold, lacquer, porcelain and stone illustrate the transformations of indigenous motifs and techniques into dynamic new art forms expressing the message of the Prophet Mohammad. The carefully selected works of art demonstrate how ideas and images from the Middle East, Central Asia and Mughal India have interacted over centuries with local beliefs and ancient traditions

From the religion’s first arrival in Southeast Asia almost 800 years ago in ships carrying Muslim traders from the Arab world, India and China, Islam has been embraced enthusiastically by royal courts and rural communities across the region. In an innovative overview of the interchange between these cultural traditions, sumptuous gold heirloom jewellery and regalia from the royal sultanates of the archipelago are exhibited alongside Aboriginal bark paintings from Arnhem Land depicting the Muslim sailors who reached Australia long before Europeans landed on these shores.

Participation in a dynamic maritime culture, stretching from the Middle East to south China, ensured that artists of Islamic Southeast Asia were exposed to a wide range of decorative styles and forms. In particular, Crescent Moon celebrates the diversity of Islamic designs arriving in Southeast Asia on the winds of foreign trade and cultural exchange: centuries-old richly-dyed Indian textiles and elegant Chinese ceramics and cloisonné have long been prized throughout Southeast Asia.

The exhibition reveals the sophistication and splendour of the Islamic courts in the archipelago. Royal heirlooms recall a glorious past when wealthy courts, enriched by the spice trade, competed to demonstrate divine blessings through earthly power and material luxury. Lavish ceremonies of the life cycle, such as circumcisions, weddings and funerals, were testimonies of faith and power when displays of fine gold and silver royal regalia and invincible weapons of state, encrusted in precious stones, dazzled the audience.

The exhibition also illustrates the contribution of Islam to the arts of Southeast Asia. The written word – the embodiment of the Divine in Islam and the illustration of the holy Qur'an – has everywhere been fundamental to Islamic art and Southeast Asia was no exception: Crescent Moon displays more than twenty Indonesian and Malaysian gold-illuminated manuscripts, including a rare Qur’an from Aceh. Islamic calligraphy is also shown on fine textiles and costume, ornate architectural details, and in panels of composite Arabic letters depicting birds and animals.

Crescent Moon brings together a hundred valuable loans from museums, palace treasuries and private collections of Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei, displayed alongside objects from Australian institutions, in particular textiles from the National Gallery of Australia’s spectacular collection of Southeast Asian textiles, and Islamic ceramics from the Art Gallery of South Australia.

The exhibition is accompanied by a richly illustrated full-colour catalogue with texts by renowned Australian and international scholars.

Organised by the National Gallery of Australia in partnership with the Art Gallery of South Australia.

Sponsored by Santos and the Gordon Darling Foundation

Themes

Islamic art and civilisation of Southeast Asia

Muslim sea voyages into Southeast Asia over one thousand years ago set in motion cultural transformations of great significance. From the Arabian peninsula, Persia, Turkey and, later, Mughal India and even southern China, traders and wandering teachers, often adherents of Sufi mystical practices, introduced Islam to mainland and island Southeast Asia where the new religion spread amongst the royal courts and maritime societies of the region.

The revelations of the Prophet Muhammad (570–633) emphasised a spiritual code that encouraged a holistic view of life including art. Islam permeated all elements of life, inspiring the creation of beautiful objects for both religious and decorative purposes. Throughout the Islamic world, however, regional aesthetic styles remained evident across different artistic media including manuscripts, stone and wood carving, metalwork, ceramics and textiles. Both believers and non-believers created art for Muslim communities, contributing to a unique and vital Southeast Asian Islamic heritage, which reflected the multiculturalism and diverse local histories of the region.

Today Southeast Asia supports around one quarter of Islam’s global community. In Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei, the majority of the population is Muslim, while in Singapore, the Philippines, Thailand, Cambodia, Burma (Myanmar) and East Timor there are significant Muslim minorities with their own distinct art and cultural identities.

Art and pageant

For centuries Muslim societies have celebrated public events and royal rites of passage, such as coronations, marriages, circumcisions and visits from foreign embassies, with spectacular processions on land and water. Giant carriages and boats, often in the form of legendary creatures, accompanied these parades that were made festive with the unfurling of banners and the sound of ceremonial cannon fire. These were often occasions when communal identification with Islam was made evident in the ornamentation of fine objects with Arabic calligraphy.

The colourful art made for such customary occasions was, however, often ephemeral and few such objects have survived. Nevertheless those that do testify to the rich legacy of Islamic civilisation in Southeast Asia and to widespread forms of popular art that have now vanished.

‘God’s shadow on earth’

The rulers and aristocratic elite who were among the first Southeast Asians to adopt Islam created an elegant cultural heritage still evident today throughout the region. Royal patronage ensured that the most lavish art was produced for court circles. Fabulous displays gave visual expression to the Islamic notion of the sacred role of kingship.

The spectacular regalia and costume worn in court ritual was intended to emphasise the sultan’s power and promote the allegiance of his or her followers. Moreover, the validity of a ruler’s mandate over the principality depended on the possession of ancestral heirlooms, known as pusaka, in the form of ceremonial weapons, textiles and other objects.

Gold, with its rich symbolism and high worldly value, was the preferred medium for royal regalia. The colour was compared to the sun whose orb was a metaphor for the universal monarch and whose radiance was seen as akin to the light of God’s blessing. Gold objects became symbols of the prestige and wealth of the court throughout Southeast Asia.

The draped universe of Islam

Many of the most sumptuous textiles produced in Southeast Asia were closely associated with the Islamic courts of the region. Garments and ceremonial hangings were created in a variety of techniques, including brocade and tapestry weaving, embroidery, intricate tie-dyeing, finely waxed batik, and gold-leaf embossing, often from imported luxury threads of silk and gold. Among the most elegant are the songket floating weft brocades, most closely associated with the Malay sultanates.

The richly decorated textiles, almost invariably made by women, display a variety of auspicious motifs drawn from indigenous and foreign sources. A prominent feature of palace ceremony and rites of passage, including birth, circumcision, marriage and funeral ceremonies, their display symbolised the pivotal position of the sultan between the older world of local ancestral tradition and the lively sphere of international maritime exchange.

Sculpture and Islam

The uncertainties of time and the tropical elements have not favoured the survival of wooden objects in Southeast Asia, yet wood was the most popular material for male artists in Islamic societies. Carved wood was used to ornament mosques and palaces, as well as to create utilitarian objects whose decoration drew inspiration from the natural world.

Many aspects of the development of early Islamic art in the region are not yet well understood. However, it is clear that Islamic architecture and ornamentation grew out of and absorbed numerous elements of previous Hindu-Buddhist styles, as did other art forms such as drama and puppet theatre.

Fortunately a small and unique collection of sixteenth-century wooden carvings has survived in the Kraton Kasepuhan palace in Cirebon, west Java, Indonesia: some of these important cultural treasures have been generously loaned to this exhibition. Established by the Muslim saint Sunan Gunung Jati, the Cirebon kraton is the oldest continuously occupied Islamic palace in Southeast Asia. It provides intriguing insights into the history of Islamic civilisation in the region.

Trade winds and the international identity of Islam

Southeast Asia was a key player in a dynamic network of cultural exchange extending from China to the Middle East and eventually to Europe. Indian textiles and Chinese ceramics were popular products in the vigorous spice trade across all of the communities of Southeast Asia regardless of religious orientation. However, many designs and styles on these imported luxury items were created specifically for Muslim clients and became integral to the history of Islamic art in Southeast Asia.

Brightly dyed Indian silk and cotton cloths were especially popular in the sultanate courts and their patterns inspired local textile designs and motifs. The early production of Chinese export porcelain was a direct response to the fashionable tastes of the Muslim world: their presence in Southeast Asia documents the region’s active participation in the international culture of Islam.

Many of these exotic items acquired status as ancestral heirlooms in both court and village and have been passed down over generations by Muslims and non-Muslims alike. Their preservation and survival can be attributed to their value as items of ancestral heritage.

The Word

Calligraphy is the noblest of all arts in Islam and, as the word of God recorded in the Qur’an can only be written by a pious believer, the calligrapher is the quintessential Muslim artist.

In Southeast Asia, as in other parts of the Islamic world, the decoration of the sacred texts, especially the Qur’an, demonstrated the believer’s deep faith and reverence. Rulers and religious institutions sponsored the production of illuminated manuscripts in local ornamental styles and sometimes in regional languages, such as Bahasa Indonesia and Malay, which were transcribed in an Arabic-based script.

The Arabic language became the central symbol of Islam. Verses from the Qur’an, pious injunctions and prayers, and talismanic grids filled with Arabic numerals, intended to evoke divine protection and blessings, were inscribed on objects in every conceivable medium. The decoration of objects with Arabic calligraphy also signalled to the wider community, the devoutness of the creator, owner or wearer.

Arabic scripts are read from right to left.