Dance Hall Days

French posters from Chéret to Toulouse-Lautrec

27 Jun 1998 – 25 Oct 1998

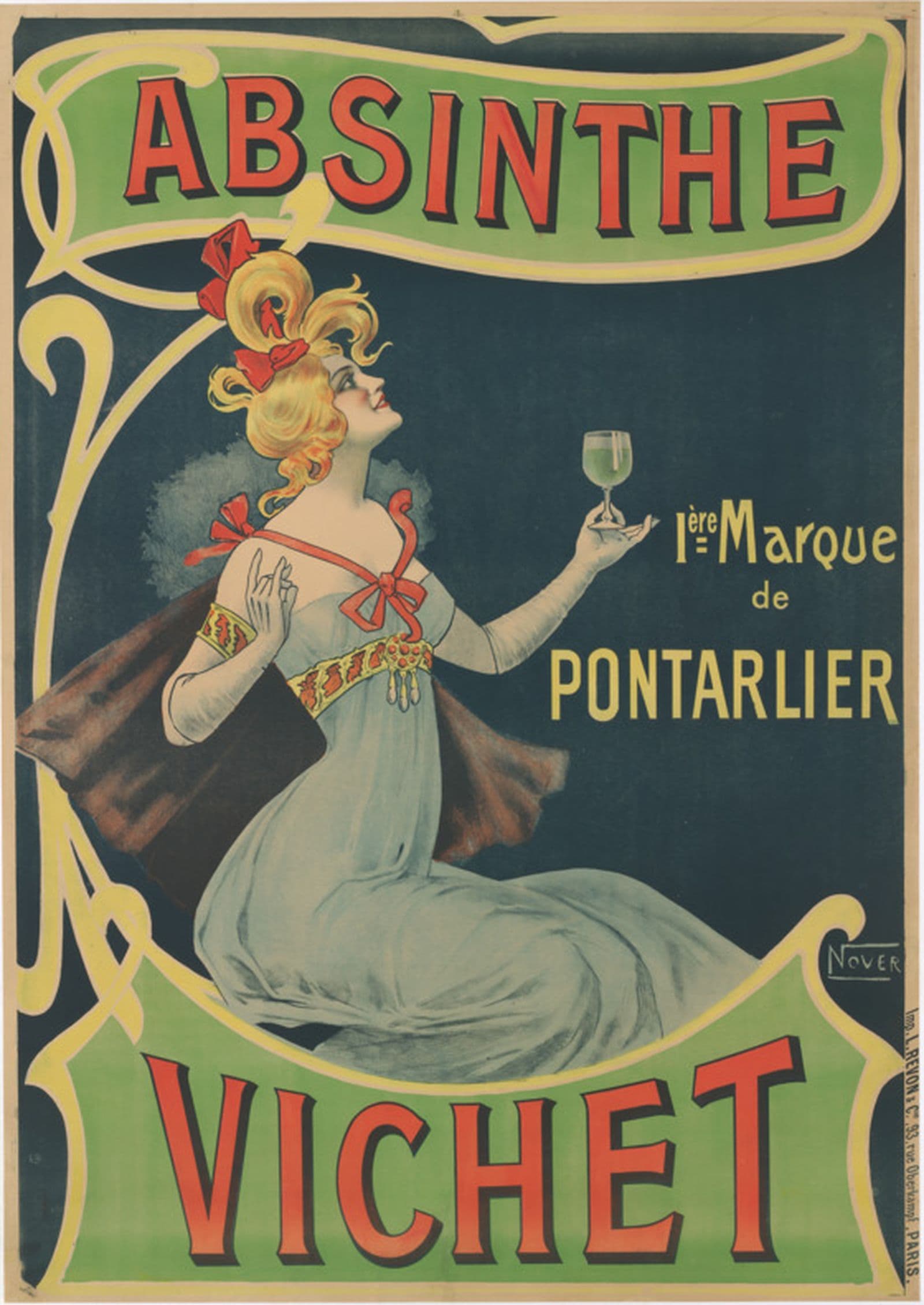

Nover, Absinthe Vichet, 1900, gift of Orde Poynton Esq. CMG 1996

About

In the latter half of the 19th century a new art form appeared on the streets of Paris – the colour poster. Many of these vivid images advertised and celebrated the popular dance halls and cafés-concerts. Venues such as the Folies-Bergère, Alcazar, Moulin de la Galette, Elysée Montmartre and the seedier Moulin Rouge were frequented by a wide range of patrons.

These venues attracted everyone from aristocrats to young working girls. Crowds of merrymakers, pleasure seekers and demi mondaines mingled, flirted, danced and caroused, entertained by performances which, as one commentator put it, were often concerned with 'matters below the belt'. By the 1890s, these venues were found throughout the city and its environs, catering to locals and tourists alike.

The content on this page has been sourced from: Chéret, Jules, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Dance Hall Days : French Posters from Chéret to Toulouse-Lautrec. Canberra: National Gallery of Australia, 1998.

Poster Madness

Once regarded as simply a form of advertising with little artistic merit, posters became more beautiful, more colourful and more daring during the last decade of the 19th century.

Colour lithography was the ideal printing process for posters. Artists drew directly on a limestone block with a greasy medium which absorbed ink. The directness of this method and the use of refined inks, giving purer, bolder colours, attracted artists in increasing numbers. Their art was brought to the streets in brightly coloured posters that could be printed in almost unlimited numbers.

As posters became more popular, entrepreneurs seized upon the opportunities for mass promotion inherent in this medium. At the same time, collectors began to seek out the latest works of up-and-coming artists. Posters were used to decorate the home, and albums and portfolios of miniature versions of popular images – such as those in Les maîtres de l'affiche (The masters of the poster) – catered to this fashion. Nowhere was 'poster madness' more widespread than in Paris – the quintessential European capital. Its grand boulevards bustled with bohemian strollers and fashionable promenaders. A city of delights, its cafés, delicacies, services, consumer products, exhibitions, circuses and dance halls – even its dives and more down-at-heel inhabitants – all became the subjects of posters that papered the streets and were sought by connoisseurs.

Jules Chéret was at the forefront of the poster revolution. He had honed his large format printing skills while working in London for the cosmetic company, Rimmel. After his return to France in the 1860s, his reputation and popularity grew. Chéret developed a simplified system for printing in three colours (later expanded to five) from separate lithographic stones, and also perfected the use of graduated colour from warm tones at the base of the composition to cool tones above. His method resulted in bright and memorable compositions that avoided the cheap colour `stews' which had previously given colour printing a bad name.

Multicoloured Laughter

Chéret's posters advertised everything from gasoline and bookshops, to hats and circuses. However, it is in bright banners for dance halls and café-concerts that his style is given its full expression. Described by one contemporary critic as `a burst of multicoloured laughter', his posters are full of the gaiety and vivid colour of the world of Parisian entertainment.

In 1889 Chéret was commissioned to design a poster to advertise the opening of the Moulin Rouge. With pretty Rococo-inspired young blondes, which became known as `Cherettes', he created a vibrant image redolent of gaiety and escapism. The following year, Chéret designed a distinctive poster for a masked ball at the rowdier Elysée Montmartre. He also created numerous designs for another café-concert and music hall, the Folies-Bergère, and was influential in establishing the career of a dancer who appeared there: Loïe Fuller, an American who made her name in Paris as one of the principal performers at the Folies-Bergère and was best known for her spectacular danse de feu (dance of fire).

Alphonse Mucha followed in Chéret's footsteps, designing posters to advertise forms of entertainment, as well as personal and household products. Mucha differed from Chéret stylistically; he became known for his sensual, exuberant interpretation of Art Nouveau. This style emerged in Paris in the 1890s, born of a love of decoration and inspired by organic forms. Mucha's poster art featured swirling sinuous lines and rounded female forms, as seen in his poster of 1894 advertising Job cigarette papers.

Mucha first became known through his association with Sarah Bernhardt, a principal figure on the Paris stage. In a series of lifesize posters, Mucha successfully translated Bernhardt's dramatic qualities, capturing for example her portrayal of Medea, from the classical tragedy Médée. As well as the publicity, Mucha's posters afforded Bernhardt the opportunity to market copies to a growing clientele of collectors who had succumbed to 'poster madness'. She scrutinised such ventures carefully and they brought her handsome financial rewards – in one instance she took the noted printer Lemercier to court over copies of an edition that went missing.

From Public to Private

Poster art was not simply advertising, it was also art with a message. The artist Théophile Steinlen, for example, was inspired by the social realism of author Emile Zola, and he allied himself and his art with the downtrodden. Zola's influential novel, L'Assommoir – which told the story of city life, poverty, and the decline into alcoholism and prostitution – was adapted for the stage in 1900. Steinlen designed a poster for this production, showing the figures of the protagonists, Gervaise and Coupeau.

Steinlen's massive masterpiece of poster-making, La rue: Affiches Charles Verneau (The street: Charles Verneau Posters) 1896, also addresses the theme of city life, not on the grand boulevards but in a backstreet of Montmartre. La rue explores the diversity of the capital's populace, depicting a variety social types. In this he follows in the footsteps of the great writer Balzac and caricaturist Daumier, both prominent in France earlier in the century.

As posters became bolder and more dramatic, there was a concurrent realisation that they could convey political messages to great effect. The socialist and activist Marguerite Durand commissioned Clémentine-Hélène Dufau to design a poster for the influential feminist journal La fronde (The sling), published in Paris from 1897. In her poster Dufau depicts women of means and education standing next to their less fortunate counterparts; one points in the direction of the Sorbonne, making the point that education offers a means of improvement.

As more artists became involved in poster-making, this medium of mass communication began to treat more personal subjects. Pierre Bonnard strove to make his art relevant to his times and was keen for it to have practical application. He belonged to the Nabis, an avant-garde brotherhood who wanted to extend their ideas on art to all facets of life, valuing the decorative arts, and print and poster-making as well as painting. According to Bonnard, artists of his generation 'always sought to link art with life'. Bonnard was drawn to poster-making, and it was towards the end of March 1891 that his first poster, France-Champagne was pasted up in the streets of Paris. The impact was immediate and its success helped to propel Bonnard to prominence in the art world.

Bonnard and the other Nabis had particularly close ties with a French journal, La revue blanche. The driving force behind the publication was Thadée Natanson, a young intellectual who sought to become a figure of consequence in the French art world. In 1984 Bonnard was commissioned by Natanson to design a poster to advertise La revue blanche. The resulting poster featured Misia Natanson, a gifted pianist who was also the wife of Thadée. In this work, Bonnard continued his radical experiments in poster design: this intimate portrait of a vivacious woman combines a masterful use of caricature – a genre then undergoing a revival – with dramatic flattened space and sombre colouring.

Bonnard's poster France-Champagne is generally credited as the catalyst for Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec's embrace of poster-making. Toulouse-Lautrec was a superb draughtsman who came to value poster-making and printmaking on a par with painting. He revelled in his subjects – the dance halls, bars, theatres, race tracks and brothels – and executed his posters with an acute and penetrating observation that rivalled painted portraits of the day.

One of Toulouse-Lautrec's favourite subjects was the dancer Jane Avril, who made her name at the Moulin Rouge, a dance hall frequented by the artist. Avril appears in a large poster of 1893, performing at the café-concert known as the Jardin de Paris (Garden of Paris). Her 'serpentine' movements and high kicking can-can were well suited to Lautrec's sinuous lines. Her morbid character also appealed to the artist's dark disposition.

Toulouse-Lautrec did not simply depict the night life and low life of Paris. Passenger from cabin no. 54, for example, is quite personal in tone. It is based on the artist's reminiscences of a voyage he made from Le Havre to Lisbon during which he was so enamoured of another passenger that he failed to disembark at his destination. This poster reveals the artist's debt to Japanese art, as evidenced by his use of strong lines, flat colours, beautiful patterning and a cropped composition. It is also indicative of the subtle colour that could be achieved in lithographic poster-making using spatter lithography – a technique whereby a midtonal range was created with a series of tiny dots.

A poster such as Passenger from cabin no. 54 indicates just how far the poster had progressed as an art form in just a few decades. Once destined only for the street, posters became sought-after for the home, as artists of the calibre of Toulouse-Lautrec brought the qualities of great intimacy to an art of the mass media.

Jane Kinsman

Senior Curator, International Prints, Drawings and Illustrated Books