Fred Williams

Painter/Etcher

7 Jul 1981 – 10 Sep 1981

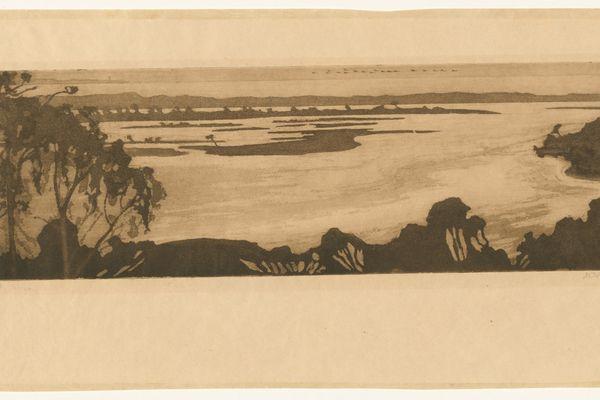

Fred Williams, Circular hillside landscape., 1965-66, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, Gift of Lyn Williams 1987. © Estate of Fred Williams.

Director's Introduction

Very few until now have seen enough of Williams’s work to realise the interdependence of his paintings, drawings and prints. This exhibition the first in which an attempt has been made to show diversity of working methods Williams has employed in his search for style.

Etchings may start from drawings, gouaches, oil paintings or from other prints, and there have been times when Williams’s painting has been given a new direction from what he has been able to achieve through the print process. When there is a direct translation of a subject from one medium to another we see the transformation of the image into marks appropriate for that medium.

Williams is equally fascinated by the changes that take place when the same subject is redrawn on a different scale. He will try for the same sense of space in a composition whether it be a large canvas or the more intimate scale on a small piece of metal. The only certainty with his method is that the starting point is always in something seen and recorded.

The first marks towards a decisive image may be tentative. Works such as Drawing for cook and time clock have seldom survived, just as the first painting made on a days outdoor painting trip, though an accurate record of place or weather, may lack the stamp of Williams and be discarded. On the other hand, etchings like Feeding the pigeon may be well resolved as they are drawn. Such images only need the various disciplines of the etching craft to complete them.

Williams is a well trained artist and it was natural for him to consider making etchings while he was studying in London from 1951 to 1956. He says that the first music hall drawings were made at the Metropolitan, the Chelsea Palace and other music halls because it was cheaper to be warm there in winter than it was to be at home where the gas meter consumed shillings.

The correct order in which the etchings were made may one day be established when Willams allows access to his diaries where, by means of small drawings, he describes work done during the day. Similarly when he allows full access to his store, we will find more paintings that will help us to understand the interaction between painting and etching throughout his career.

I was first shown the London drawings in 1960 and did not see them again until a month ago, when, for the first time, I saw the music hall gouaches and other paintings from the London etchings, such as The haircut and Washing. These were among the first things Williams painted after his return to Australia in 1957.

Vaudeville was the first etching and we can now see how it evolved from two drawings similar to many others drawn from performances on the stage. Not unexpectedly the print is clumsy but it contains two of the constants in Williams’s work: the gain in energy that results when he translates marks made in one medium into marks appropriate to another; and the risk he is prepared to take to realise his intention, seen here in the repositioning of the head in the larger figure. Williams has repeated the story that Rembrandt was prepared to make alterations to his etchings until his plates had holes in them, and although there is no evidence of such holes in Rembrandt prints, in Sherbrooke Forest number I Williams worked the plate until it was so riddled with holes he could do no more with it.

Williams often paints a number of versions of a motif before he finds what he is after in the painting in front of him, but having found a starting point, he will sometimes work the motif until it can support no further variation. The print, Knoll in the You Yangs one of the largest and certainly the most laboured of all the prints, began as a gouache made out of doors which was worked up into Williams’s largest painting to 1964. Before the painting was finished the plate was cut into two and the resulting parts were worked to make two prints that can be considered independently. Then followed a drawing from the painting in a new broader manner, with the last essence being extracted from this landscape in a large gouache of around 1966 which follows the etching on a smaller plate.

Williams’s pursuit of a final image over many years is not uncommon: music hall subjects etched in 1954 from earlier drawings were finished in 1966. This exhibition is in many ways of work in progress, as landscape etchings begun in 1968 still have to reach a final state and be editioned.

Everybody who has had to select Williams’s work for a collection, exhibition or publication has realised the complexity of it. We hope some of this is conveyed in this exhibition.

We are grateful to the artist and his family for allowing us to exhibit this selection from the prints, watercolours, gouaches and oils that are on deposit from them at the Australian National Gallery.

James Mollison, Director, Australian National Gallery

Canberra, May 1981

The Printing Process

Except when they are obviously lithographs or linocuts, Fred Williams always refers to his prints as etchings. Technically, this is a simplification; many of the prints begin as drypoints and are worked up to include engraved lines, areas of aquatint and foul biting, and in recent times marks made by mezzotint rocker, scrapers, burnishers and various commercial hand engraving tools. Except for the latter, these are the traditional tools of printmakers who, as in Williams's case, work the different techniques as they are expedient to control the blending of tones, lines and textures or to execute contrasts between them. The correct technical term for such prints is intaglio prints.

Etching

Etching is a process that uses the chemical action or bite of various acids on metal to deepen lines drawn through an acid resisting ground into the metal of a plate. The strength of any etched line depends on the length of time the plate has been left in its bath of acid, the variety of acid used and the length of time any batch of acid has been in use.

If after proofing the plate, the artist realizes that some of the lines are etched deeply enough to print according to his intentions, but wishes to strengthen others, the satisfactory parts can be stopped out with varnish and the remainder of the plate can be further bitten. Occasionally an entirely new ground will be applied over the plate and further lines can be drawn into that before the whole plate is rebitten. However, it is more usual for Williams to take up other tools and work directly on to the plate to ensure the completion of an image rather then to rebite it a number of times.

Plates

Any flat sheet of metal that will stand the squeeze of the printing press can be used for etching. Copper is the metal traditionally used, although occasionally prints are made from brass plates. Williams has also used zinc plates, initially because they were cheaper but more recently because the metal is softer and can be scraped and burnished to print with particular characteristics. The surface into which the image is initially drawn has to be highly polished so that areas intended to be white, generally background areas, can be wiped clean of ink. The edges of the plates are bevelled and the corners rounded to prevent the paper tearing at the corners and along the plate mark during printing

Inking

Printing ink is stiff and tacky and difficult to spread unless the plate onto which it is applied has been warmed. The ink must be pounded on to the plate with a wad of cloth to fill the pits, scratches and incisions that have been made by various means into the polished metal surface of the plate.

Wiping

After the plate has been inked all over, it is then gently wiped with a coarse cloth to remove the first of the surplus ink from its surface. The aim is to wipe clean the polished surface which will then print without tone. The final wiping of the plate is carried out with the ball of the hand. It is possible for a skilled printer such as Williams to leave various films of ink on the surface of a plate so that an attractive plate tone results.

Printing

After wiping, the plate is laid face up on the bed of a press and is covered by both the dampened sheet of paper that is to take the impression and a number of felt blankets. This sandwich passes through the press under some tons of pressure which forces it into all the ink-filled depressions in the plate. Close inspection of an intaglio print reveals that the ink actually rests on raised lines where the damp paper has been forced into the ink-filled marks on the plate. All the impressions in an edition have to be laid aside for both the paper and the oily ink to dry. Printing is difficult and time consuming and much practice is required to pull a uniformly good edition. Some plates require careful or subtle inking to make them effective.

Plate tone

Prior to 1966, prints with a tone from ink left on the surface of the plate were unusual. The great majority of early impressions were from plates wiped clean of surface ink. Recently, however, there has been some experimental wiping of the plate and Williams has said he is interested in producing a series of exceptionally carefully wiped and attractive impressions.

Proofs

The term proof refers to those prints which have been pulled by the artist to see how the plate prints. These are often roughly printed. In the case of certain of Williams's prints they once existed in very great numbers. The plate Knoll in the You Yangs (57b) at one time existed in 35 different states. Proofs are usually taken for the information of the artist and are often spoilt, frequently with ink marks from the printer's fingers. At times they are allowed to lie one on top of the other and at the end of a days work, proofs are frequently seen to be smudged. Where Williams found proofs to be too damaged, or not exhibitable or specially informative, he discarded them.

Counterproofs

Williams often uses counterproofs to enable him to check on his work. A counterproof is taken from a freshly printed proof by returning this with a clean piece of paper through the press. It is a mirror image of the original proof and the same way round as the image on the plate. Changes are often marked on to counterproofs because from them the artist can work directly on to the plate without having to think of his drawing in reverse. Williams is one of the few artists ever to have made editions of counterproofs. When the lines in a plate are deep and rich with ink, returning an impression through the press flattens the relief and spreads the ink. While this may look good in a counterproof where the new broader quality is attractive, the etching from which the counterproof has been made is usually spoilt.

States

By examining all the known impressions of a print, it is possible to identify the number of times the artist has worked on the image after proofing. Each time an artist prints from an altered plate the work is said to be in a new state. States are described sequentially — first, second, third, etcetera — and record prints are taken after the first alteration, second alteration, etectera, to the plate.

Editions

Occasionally an artist is satisfied with a print on seeing it as a first state proof, and prints a number of impressions. These are numbered and the size of the edition is recorded, e.g. 1-10, 2-10, 3-10 and so on. He sometimes decides to work further on the plate and take it through a few or many more states before he prints another edition.

In Williams's case plates that were at one time set aside, finished or unfinished, have been reconsidered years later and either worked, cut down, reprinted on a new kind of paper or used to give him a lead into work in some other medium. The fear of altering a plate and by doing so destroying it does not prevent Williams from reckless action on his plates. His aim is to fully work out an idea.

Drypoint

Drypoint is a more direct technique than etching A hardened, sharp metal point is used to scour lines into the surface of a plate, usually in such a fashion as to turn up an edge of metal called a burr to one or both sides of the line. Williams has a very strong wrist and frequently tears such a burr of metal from the plate that the ink held by it can't be wiped cleanly from the surface of the plate. This then prints with a characteristic dark velvety quality which indicates drypoint burr. Used lightly to merely scratch the plate, drypoint holds very little ink and produces an effect of fine pale lines. Drypoint yields a limited number of good impressions since continual wiping of the plate to clear the surface of excess ink quickly wears away a burr and pressure in the press displaces the metal edge. It is always possible to pick those drypoints which were printed first in an edition from those that came at the end of it.

Engraving

Engraving is the process of making lines directly into the surface of the plate with a burin. A burin is a chisel-like tool of hardened metal. It is quadrangular in section and sharpened to a point at an angle. Used traditionally, the burr thrown up by the gouging action of the burin is burnished away so that the engraved lines print clearly. However, Williams does not always do this and at times his engraved lines print with some of the effect of drypoint. Engraved lines can be distinguished from drypoint because they print in slight relief.

Aquatint

Aquatint is the technique most commonly used by Williams to create areas of dark tone. It is frequently used in his early prints. To make an aquatint ground, powdered resin is put into a closed box, shaken and the plate to be aquatinted placed inside. Resin dust settles over the surface of the plate, and the longer the plate is left in the box the greater the concentration of resin dust on its surface. After the plate collects the amount of resin suitable to the artist's purpose it is taken from the box and heated to make the grains of resin melt and adhere to the plate. It is then placed in an acid bath. The resin protects the surface of the plate and the acid bites the spaces between the grains. Aquatint can be very fine or coarse grained, depending on the size of the resin particles used. It can be supplied repeatedly in successive states or in different places on the plate over stopping-out varnish.

Flat Biting

Williams sometimes flat bites his plates by dropping them momentarily into a bath of acid so that the resulting light bite slightly corrodes the surface of the plate which the prints with a faint all-over tone. Unless flat bitten plates are carefully printed it is sometimes difficult, without seeing all the prints in the edition, to detect this process.

Rough Biting

In rough biting the artist paints with a feather and strong acid directly on the surface of the plate. This corodes the metal and creates a tonal effect like that of roughly applied watercolour.

Foul Biting

The term foul biting traditionally indicates that faults have been printed. These are generally fine lines or spots caused by acid accidentally penetrating a faulty ground. Areas of foul biting are sometimes induced by Williams who enjoys the accidental effects that result.

Touched Impressions

There are many touched impressions among Williams's prints. These may be altered with pencil; Indian ink lines and washes; smudges, tones and marks made with a finger, and pencil or printing ink. Touched proofs often allow us to see some of the alternative ideas the artist has had about altering the image on a plate. Touched proofs and counterproofs rarely survive though they are frequent enough around the studio while work is being carried out on the plates. Among the early editions of music hall subjects the practice of working all over the prints of an edition with washes of ink was not uncommon, and some editions of the London genre subjects have been uniformly touched with printing ink to make them darker in parts.

Cancelled Plates

Traditionally, when an artist has finished printing an edition of prints he cancels the plate. Williams's method of cancellation is to score lines through the image. Williams is generally reluctant to cancel plates unless they are worn, damaged or spoilt because he believes that it may be possible through either drastic changes or minor corrections to improve the print.