Imagining Papua New Guinea

Prints from the National Collection

8 Oct 2005 – 12 Mar 2006

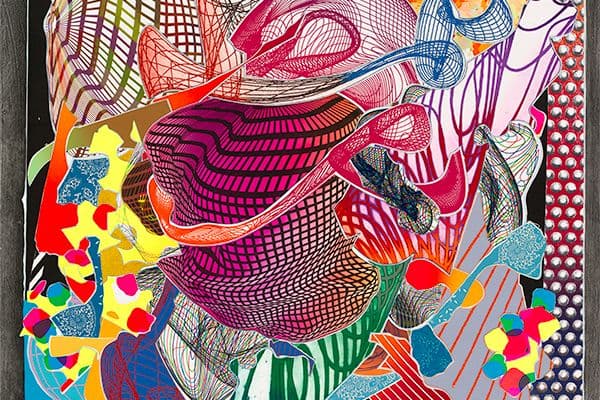

Mathias Kauage, Independence celebration 4., 1975, screenprint, printed in colour inks, from seven screens, 50.2 h cm, 76.4 w cm, Ulli and Georgina Beier Collection, purchased 2005.

About

After generations of colonial rule, the free nation of Papua New Guinea was established in 1975. Imagining Papua New Guinea celebrated 30 years of independence of Australia’s nearest neighbour.

Stories and images, both traditional and imaginary, are recorded in pen, pencil, woodcuts and screenprints – all new forms of expression to artists from the region. These prints and drawings, produced in the years around independence, showed ways in which Papua Niuginian artists responded to their contemporary world. These visions confronting the modern world encompassed its social structures and technologies, and delighted in the patterns and textures of these mediums to create fantastical creatures, both real and imagined.

Curator: Roger Butler, Senior Curator, Australian Prints, Posters & Illustrated Books

This exhibition was sponsored by Australian Air Express

Exhibition Pamphlet essay

Printmaking in Papua New Guinea

Limited edition printmaking was introduced into Papua New Guinea in the late 1960s and reached its peak of popularity in the 1970s. The practice began to fade in the 1980s and has now virtually disappeared. The prints produced belong to a specific period of social, political, artistic, literary and educational change in Papua New Guinea. Created by artists from a diversity of backgrounds, the works present strong and vibrant images that continue to resonate.

On 21 November 1969 an exhibition of woodcuts by Mathias Kauage and screenprints by Taita (Marie) Aihi and English expatriate Georgina Beier opened at the University of Papua New Guinea’s Centre for New Guinea Cultures in Port Moresby. The show, probably the earliest to include prints by Papua New Guinean artists, was organised by Georgina and Ulli Beier.

Aihi, a Roro woman from Waima, was 18 years old and had lived most of her life on Yule Island Catholic Mission when she met Georgina Beier and was encouraged to pursue a career in textile design in Port Moresby. Kauage, on the other hand, had tracked down an initially dubious Georgina Beier after finding inspiration in an exhibition of drawings by (Timothy) Akis which she had organised in February 1969. Akis’ exhibition was extraordinary not only because the artist, from Tsembaga Village in the Simbai Valley, Madang Province, had started drawing seriously just six weeks before the show opened, but also because it was essentially the first exhibition of ‘contemporary’ art by a Papua New Guinean artist.1

Contemporary or ‘new’ art using imported techniques and materials is largely an urban concern in Papua New Guinea, with work carried out either in dedicated municipal settings, or in specific schools and cultural centres outside of them. The reasons for this are practical as well as cultural; it is in those places that the necessary equipment and materials are most readily available and ‘artist’ as a personal career choice was not, until recently, part of Papua New Guinean culture. While those with exceptional artistic skill were acknowledged and appreciated, they also participated in the everyday activities demanded by culture and survival.1 As writer, researcher and collector of Papua New Guinea’s contemporary art, Hugh Stevenson put it: ‘The idea of a person exclusively subsisting by art production and dedicated in his thinking only to art would have been exceptional’.3

During the 1960s Akis worked intermittently as an interpreter and source for a number of anthropologists, drawing in order to communicate designs or ideas that were difficult to describe in pidgin. Georgida Buchbinder, an anthropologist from Columbia University, was taken with Akis’ sketches and, when he travelled with her to Port Moresby in January 1969, showed his work to Georgina Beier who she suspected would find them intriguing. Aware of his potential, Georgina Beier encouraged Akis in his drawing.

Georgina Beier, a London-trained artist, and her academic husband Ulli Beier, had been involved in fostering and promoting contemporary African art, primarily in Nigeria, before relocating to Papua New Guinea in 1967. Art brut was also of interest and shortly after arriving in Port Moresby Georgina Beier became involved with patients at Laloki Mental Hospital, bringing them art materials in the hope that creative activity might boost their spirits.4 In the short time he spent in Port Moresby, Akis produced more than 40 drawings and a number of batiks. The works formed the basis of his inaugural exhibition. In his introduction to the exhibition Ulli Beier wrote:

'The delicate freshness of these drawings owes nothing to the traditions of his people, whose artwork consisted mainly of geometric shield designs. Unburdened by the rigid conventions of ancient traditions and uninhibited by western education, Akis created his personal image of a world of animals and men."5

Following the show, Akis went back to his village and did not return to Port Moresby until 1971. From then until his death in 1984, his time was divided between subsistence farming in the village and short periods of intensive work in Port Moresby. Although a successful and prolific artist in the capital, he appears to have made very few drawings at home.

In November 1969, a number of Akis’ earliest drawings were reproduced in the maiden issue of Kovave: A Journal of New Guinea literature. Conceived by Ulli Beier, who lectured in literature at the University of Papua New Guinea, the literary periodical also provided exposure for contemporary art. Each issue included illustrations and discussion of an artist’s work as well as artist designed vignettes. Kauage, Aihi, Kambau Namaleu Lamang, John Man and the sculptor Ruki Fame, among others, had work published in Kovave.

Kauage was one of a number of Highlanders working as labourers in Port Moresby who were invited to the opening of Akis’ first exhibition in order that the artist should not feel like a spectacle amongst the otherwise largely expatriate audience.6 Spurred on by the work, Kauage, from Mingu No.1 Village, Gembogl in Simbu, had a friend deliver some of his own drawings to Georgina Beier. Unimpressed by the pictures she guessed to have been copied from schoolbooks and magazines, she later wrote, ‘they must have looked to the artist tremendously slick, almost identical to the real thing on the overpoweringly prestigious printed page’.7 Nevertheless, she agreed to meet Kauage and the two formed an enduring friendship. Georgina Beier coaxed Kauage to draw from his imagination rather than copy ‘realistic’ illustrations and he soon gave up his job to concentrate on art. His style changed and developed quickly, reflecting his state of mind.

Now Papua New Guinea’s best-known contemporary artist, Kauage regularly exhibits internationally and has work in collections worldwide. He was a joint winner of the Blake Prize for Religious Art in 1987 and in 1997 was awarded an OBE (Order of the British Empire) by Queen Elizabeth II for his services to art. A short time into his artistic career, however, Kauage’s spirits fell and he began drawing heavy, blocky and sometimes limbless figures. It was then that Georgina Beier taught him to make woodcuts.

At this stage I introduced the woodcutting technique. His new, heavy, solid shapes were easily adaptable to this technique. (His earlier, flowing line would have been ideal for etching but I did not have the facilities for this.) One reason why I introduced the new technique was that Kauage – who had now given up his job as a cleaner and lived much better on the sale of his drawings – had time on his hands. Kauage wanted to put in a full day’s work, and no artist, however imaginative and prolific, can go on producing new ideas for drawings all day long, every day. The woodcuts allowed him to relax a little. He produced very fine work in this medium, but somehow he could not shake himself out of the depression completely.8

Ten woodcuts were printed in small editions, impressions from which were shown at the print exhibition in November 1969 (illus. p.58). Kauage’s woodcuts featured creatures and riders and geometric shield patterns. Initially ashamed to admit they came from his imagination, the artist is reported to have claimed the amazing images of stylised people floating above heavily decorated horses, goats and snakes were accurate depictions of scenes he had witnessed. The woodcuts and a number of other important early prints, including screenprints of Akis’ work and Aihi’s prints and textiles, were made at Ulli and Georgina Beier’s Port Moresby home, many in a backyard shed – called the ‘Centre for New Guinea Cultures’ – provided by the University of Papua New Guinea. Screenprinting from hand-cut stencils was the most commonly used technique. In 1971, however, Georgina Beier stated that she would have liked to teach Akis etching:

Pen and ink drawings provided a near perfect medium for Akis, but ideally he might have learned etching. His style demands the delicacy and soft dense texture that only etching can give. But unfortunately we had no etching press available.9

In fact, in the late 1970s a print technician at the National Arts School created a makeshift press and printed a small group of etchings taken from Akis’ drawings. Two impressions from the experimental printing are in a private collection in Canberra. Due to a lack of facilities, very few etchings by artists from Papua New Guinea are known, although there is an extremely fine and rich etching and aquatint of a pig by Jakupa Ako, Wild pig from 1983, in a private collection in Sydney.

A significant proportion of limited edition prints from Papua New Guinea were made at the National Arts School. The institution, established in 1972 as the Creative Arts Centre, grew out of the Centre for New Guinea Cultures and was expanded and renamed the National Arts School in 1 976. The name change was accompanied by an increase in funding and was one of many cultural initiatives that occurred around the time of Papua New Guinea’s Independence, declared on 16 September 1975.

Even before the creation of the Creative Arts Centre, however, printmaking was taught at Goroka Teachers College, at that time the only secondary teachers college in Papua New Guinea, and possibly also at Goroka Technical School where the curriculum included commercial design. At Idubada Technical College School of Printing and Design in Port Moresby vocational courses were taught in design, photomechanical printing, photography and commercial art. In addition, in the 1970s, some woodcut printing and stencil screenprinting was done at Sogeri Senior High School, near Port Moresby, Kerevat Senior High School, near Rabaul in East New Britain, and at Port Moresby Teachers College.10

At the National Arts School screenprints and photo-screenprints dominated but occasional woodcuts, linocuts and monotypes also appeared. According to Maureen MacKenzie-Taylor, who taught graphic design at the National Arts School in Port Moresby from 1977 until 1981, the reasons for the proliferation of screenprints produced in Papua New Guinea in the 1970s and early 1980s are largely practical. The techniques taught reflected the available facilities and the skills of the mostly expatriate teachers and screenprinting predominated as a versatile and relatively uncomplicated technique.11

Following its use to print posters by political and community groups in the 1960s and 1 970s and its ‘discovery’ around the same time by well-known artists like Andy Warhol, Richard Hamilton, Robert Rauschenberg and Roy Lichtenstein, screenprinting was also fashionable. In addition to limited edition artists’ prints, screenprinting was used to print the invitations, advertising posters and often the catalogue covers associated with the regular exhibitions of work by artists at the Creative Arts Centre/National Arts School.12

When the Creative Arts Centre was established in 1972, Tom Craig, a Scottish expatriate who had been in charge of ‘Expressive arts’ at Goroka Teachers College, was appointed Director. Students were encouraged to value and explore their cultural heritage and to express themselves through drama, dance and music as well as the visual arts. In addition, efforts were made to counter the negative art education many students had experienced previously, including schooling that focused on realistic ‘picture book’ illustrations according to an Australian syllabus. Some students had already participated in courses that incorporated the use of local designs, while others had been exposed to vehement disparagement of their artistic inheritance. In 1976 Craig wrote of the Creative Arts Centre:

It is hoped that in such an environment, where formal teaching is kept to a minimum; where art is regarded as an activity and an attitude of mind – not a discipline to be learned; where traditional skills mingle with modern technology; there will develop a form of contemporary expression which is genuinely Papua New Guinean.13

As they had been in Goroka, traditional and established contemporary artists, including Akis, Kauage, Jakupa and Fame, were invited to work at the Centre as artists-in-residence. The arrangement was described by Craig:

Artists-in-residence at the Centre are given free accommodation, a living allowance, and all necessary equipment and materials. There are no prerequisite entry qualifications and scholarships are continued for as long as the staff and students agree that the experience is beneficial. Traditional painters, carvers, musicians and dancers are invited to the Centre for varying lengths of time to work alongside the students.14

The first artists to work at the Centre were Kambau Namaleu Lamang and the illustrators John Dangar and Jimmy John. Other artists who worked there, most initially as students, include John Man, Cecil King Wungi, Wkeng Aseng, Joe Nab, Martin Morububuna, Stalin Jawa, Jodam Allingham, David Lasisi and the sculptors Gickmai Kundun and Benny More.15

As well as nurturing the original work of Papua New Guinean artists, the Creative Arts Centre/National Arts School was concerned with exhibiting and raising the profile of work produced there. The exhibitions were well promoted and frequent and works of art were available for sale, with 50 per cent of the profits going to the institution to cover the costs of materials. The introduction of photo-screenprinting equipment in 1975 meant that prints, particularly prints of drawings, could be easily produced using the technology. Photo screenprints provided multiple items that could be sold at lower prices and in greater numbers than other work. Nevertheless, hand-cut stencils continued to be used for very large prints and by those with an interest in printing. However, as Stevenson mentioned: ‘Later, when profits from school activities went into the government consolidated revenue, the number of exhibitions and the production of prints declined.’16 In 1985 a special posthumous printing of a number of Akis’ works took place at the National Arts School. The photo screenprints, along with some remaining drawings, were exhibited and sold at the School in order to raise money for the artist’s family.

Students and artists working at the Creative Arts Centre/National Arts School rarely created their own screens or printed work themselves. For many artists, prints were an aside rather than their principal form of expression, and quite a number of contemporary artists did not make prints at all.17 The practical aspects of print production were carried out by the graphics teaching staff, including Bob Browne, Maureen MacKenzie-Taylor and Kriss Jenner (Stocker) and by the technicians at the school, particularly Apelis Maniot, Bart Tuat and Kambau.

Man, Morububuna, Kauage, Jakupa, Kambau and Lasisi are among the artists who, at various stages in their careers, dedicated considerable effort to printmaking. Morububuna, from the Trobriand Islands, began working at the Creative Arts Centre in 1974 when he was 17. The style of his early work, which consists mostly of screenprints, lithographs and woodcuts, reflects his training in Trobriand wood carving under his grandfather, a renowned wood worker. Many of Morububuna’s prints illustrate stories from the Trobriand Islands using stylised motifs and imagery from the region. Two of his screenprints, The death of Mitikata and Boi, were editioned in carefully worked multicoloured versions as well as in simple single colour prints. The works were described by art historian Susan Cochrane in her book Contemporary Art in Papua New Guinea:

The death of Mitikata is an elegy to the paramount chief of the Trobriand Islands: the group of figures at the sagali (mourning ceremony) are enclosed in the shape of a tabuya (canoe prow board), surrounded by the curvilinear motifs of kula canoe carvings. In Boi, he has drawn the profile of the sea hawk, which, in an abstracted form, is one of the primary symbols in the art associated with kula (ceremonial exchange cycle). In a clever inversion, Morububuna presents the realistic bird shape, but infills it with other detailed motifs and symbols, drawing on Trobriand iconography and his own.18

Morububuna shared studio space with John Man and in 1975 they held a joint exhibition of prints, Man & Morububuna. Man, from Golmand Village in the Simbai Valley of Madang Province, took up drawing in the early 1970s and applied to the Creative Arts Centre in 1973 after hearing of the success of other Highland artists. A student at the Centre from 1974 to 1976, Man worked in Port Moresby until 1983 when he returned to Madang and continued to produce prints.

Man’s 1974, Taim ol Dok i opim maus na karai nongut turu long kaikai (The time all the dogs opened their mouths and howled because there was nothing to eat), a screenprint with areas of hand-applied colour, depicts a group of stylised creatures with wide open mouths. The careful, tendrilous work comprising fine lines and spirals probably relates to one of the many Simbai stories Man drew inspiration from throughout his career. Man’s designs relating to legends are used to show relationships between elements and are symbolic rather than illustrative or narrative and can therefore be difficult to interpret.

Lasisi worked at the Creative Arts Centre/National Arts School from 1975 until 1979. For Lasisi, who had studied art at Sogeri Senior High School, screenprinting was his chosen medium. His first solo exhibition, and the launch of his book of creative writing with counterpart screenprints, Searching, took place at the National Arts School in 1976, where 32 strikingly graphic screenprints were shown.19 In his introduction to the exhibition, graphics lecturer Bob Browne wrote:

Since his arrival at the Centre David has been struggling, as many young people do, to discover his own identity and somehow relate his village traditions to this changing society. Clearly these traditions are well established in his personality – so is Bob Dylan. David’s search is shown in these prints, and especially in his book. David is fortunate. He has the ability and the opportunity to express his feelings in written and visual terms.20

Like Man and Morububuna, many of Lasisi’s prints and stories relate to legends from his birthplace, Lossu in New Ireland. Others, however, reference popular culture and the turmoil of unrequited love. Samkuila, which shows a stylised fish within a denticulate and heavily decorated ovoid shape, describes a clan legend telling the tale of a fish which was given to a female ancestor and can now be seen in the river in the Samkuila clan’s land.

By the 1980s much of the idealism and excitement of the 1970s was lost. The ebullience and optimism of the years surrounding Independence seemed to have transformed into division and disappointment. Less money was available and many of the expatriates who had been supportive of printmaking, and contemporary art in general, had returned home. The National Arts School became run down and information about artwork being created elsewhere harder to find. In 1989 degree level courses, taught in conjunction with the University of Papua New Guinea, were brought in at the National Arts School and in 1990 it was absorbed into the University. In 1997, Cochrane wrote:

Amalgamation with the University caused some consternation, particularly as it has reduced access for people with visual skills but no formal education to a conducive environment where they could develop their skills and exhibit work. While some of the earlier graduates are now on the faculty staff – Gickmai Kundun continued as the lecturer in sculpture and Jodam Allingham was head of visual arts 1992-1993 – they have their positions because they had obtained higher degrees. Other established visual artists who hold the National Art School’s Diploma in Fine Arts and had been employed as instructors, including Joe Nab, Martin Morububuna and Stalin Jawa, were dismissed as it was held that their academic qualifications were not high enough for university requirements.21

Despite events like the 1998 handover of a European Union funded arts complex, named ‘The Beier Creative Arts Haus’ in recognition of Ulli and Georgina Beier’s contribution to contemporary Papua New Guinean art and culture, the enthusiasm of the earlier era has not returned. Creative Arts Department staff and programs have recently been cut due to a shortage of funds and work has essentially ceased.22

At present there is nowhere to exhibit in Port Moresby and artists, including Kauage, are forced to hawk their work outside hotels in the city. Artists now working in Port Moresby – Kauage, Oscar Towa, John Siune, Apa Hugo, Gigs Wena, James Kera, Maik Yomba, Alois Baunde and Simon Gende – produce paintings, mostly in gouache, as well as some drawings. Printmaking has been precluded by the materials, facilities and support it requires.23

The lively limited edition prints produced from the late 1960s until the mid-1980s by artists like Kauage, Kambau, Lasisi, Jakupa, Man and Morububuna, therefore, mark a distinct and vital period in the history of contemporary art in Papua New Guinea.

Melanie Eastburn

With thanks to Ulli Beier, Hugh Stevenson, Maureen MacKenzie-Taylor, Helen Dennett, Michael Mel, Kriss Jenner and Barleyde Katit for generously sharing with me their time, expertise and knowledge. Special thanks go to Gordon Darling, not only for making this work possible through the Gordon Darling Fellowship, but also for his considerable support and enthusiasm.

Touring Dates and Venues

2007 – 2009

Australian tour

- Geraldton Regional Art Gallery, Geraldton, WA | 14 April – 17 June 2007

- Artspace Mackay, Mackay, QLD | 13 July - 26 August 2007, Mackay Festival of Arts

- Noosa Regional Gallery, Noosa, QLD | 9 November – 5 December 2007

- Tweed River Regional Art Gallery, Murwillumbah, NSW| 13 December 2007 – 3 February 2008, Tweed River Festival

- Grafton Regional Gallery, Grafton, NSW | 12 March – 20 April 2008

- Tamworth Regional Gallery, Tamworth, NSW | 17 May – 29 June 2008

- Flinders University City Gallery, Adelaide, SA | 5 December 2008 – 18 January 2009

International tour:

- Southland Museum and Art Gallery, Invercargill, NZ | 21 February – 19 April 2009

- Aratoi Wairarapa Museum of Art and History, Masterton, NZ | 2 May – 11 July 2009