Landscape – Art

Two Way Reaction

15 Dec 1980 – 12 March 1981

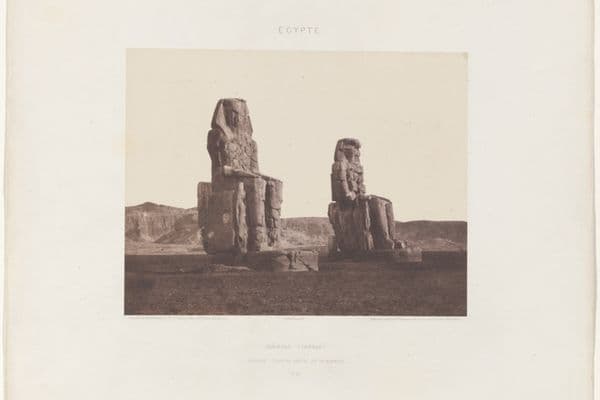

'Landscape Art: two way reaction’ at Melville Hall, ANU in 1981, featuring Nikolaus Lang ‘Earth colours and paintings’ 1978–79, purchased 1979

Exhibition Pamphlet Essay

Recently our attitude to the world and our place in it has changed. The dedication to technology of the early years of the century has been frequently questions in the last two decades. In the years since the Second World War, we have become increasingly aware of the fragility of our planet. For the first time man has realised the potential not only of destroying himself, but also of destroying the earth and its atmosphere. International Ecology Year was proclaimed in 1970; the artists in this exhibition have responded in different ways to ecological concerns.

Landscape has been a recurrent subject for artists through the centuries and during periods of increasing industrial development this interest in landscape has taken people back to their origins and to the whole issue of creation. A major artistic concern of the first half of the 20th century was with mechanical and abstract forms. Recently we have seen a return to natural sources of inspiration.

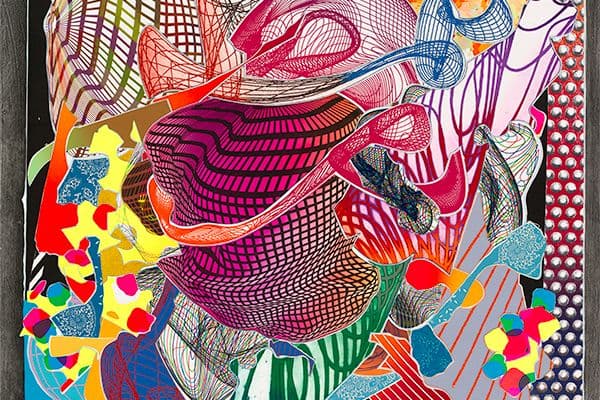

Artists’ involvement with ecology goes back to the mid 1960s. Identifying with nature, they moved away from the formalism of the earlier decade and have often seen art as a continuous process and not something that results in paintings for museum walls. We have only to compare the formalism of Ad Reinhardt’s Black pictures of the mid 50s and 60s with the open-ended concerns of Hamish Fulton’s photographs of walks, which chart the artist’s own ephemeral imprint on nature. Minimal art in the 1960s represents the last development of abstract art; it was a reduction of artistic forms taken to its limits. Works like Don Judd’s Boxes of the 1960s* represent a total rejection of natural forms to create ideals, basic aesthetic objects. Environmental art is a rejection of such aestheticism; it seeks to return to a vision of nature and reaffirms the place of the natural world as the source of inspiration. The artists in this exhibition, like the landscape artists of the romantic period of the early 19th century, are trying to integrate their experience with the continuing forces and energies of nature.

These artists are not limited by conventional pictorial space on a two dimensional flat surface, nor do they want to be confined by a museum space. Their art interacts with unlimited space, with the elements of earth, air, water and fire, the elements of creative process. A good example of this harnessing of the elements to provide an artistic insight is Dennis Oppenheim’s work, Narrow Mind of 1977. The work lasted for ten minutes. Set in the landscape between the rigid and parallel lines of a railtrack, the fleeting image of the title Narrow Mind was written in luminous but evanescent flares.

All artists reveal different preoccupations in response to their environment and hence their art. Some artists, like Sonfist and Boyle, use technology to express the beauty of nature. Smithson’s Spiral Jetty draws new life and vision out of an abused and exhausted landscapes. The sites for his work are rugged and lacerated stretches of land which have been stripped of their energy mostly through mining. He reclaims these wastelands through his art. Smithson rejects mechanical processes, yet ironically, the land is reshaped by using industrial machinery, bulldozers, trucks; he also uses aeroplanes to record the work itself. The process of making is an important aspect of such works; it replaces the mystique of the hand-finished object. Smithson’s is a grand scale vision of simple forms. There is a moral content in his attempt to bring life back to the denuded earth.

Another attitude can be seen in the work of Long, Fulton, Wolseley, Davis and Singer. These artists tread lightly in their environment. Their way of dealing with the landscape recalls man’s early co-existence with and reverence for natural forms. Wolseley’s relationship to the landscape and his drawings of grasshoppers are reminiscent of botanical drawings carried out by 18th and 19th century artists who accompanied scientific expeditions. His journey in search of grasshoppers, small vulnerable insects, delicately drawn, are metaphors for the fragility of ecological systems. His art recalls the romantic artist’s sense of wonder and his desire to understand and be at one with the forces of nature. In a nomadic spirit, some artists have moved into the landscape and made their art there; others, like Arnoldi and Ralph, have used its materials in the original form. Arnoldi makes rectangular constructions with branches and twigs which he joins to form irregular shapes. The open linearity of the twigs, like a web, cuts into space. David Ralph’s chair is an individual, handcrafted functional object. Exquisitely made, it reflects the craftsman’s sensitivity to his specific materials and at the same time challenges in a general way the undifferentiated character of international industrial design.

All art present the possibility of dialogue and interaction. This new art form interacts with the past; it is a living response to the decade preceding it as well as being a reminder of the continuing landscape tradition. The new art form seeks to awaken our consciousness to the ever-present issues of art and life.