Recent Australian Photography

From the Kodak Fund

05 Oct 1985 – 09 Feb 1986

Exhibition Pamphlet Essay

For the last three years KODAK (Australasia) PTY LTD have provided funds for the Australian National Gallery to purchase the work of younger Australian photographers. They have enabled the Gallery to acquire twenty-five works by young established photographers and also to bring into the collection forty works by some of the photographers who have emerged since 1980.

By the early 1970s artists began to use photography as naturally as they had previously used painting or sculpture. The seventies is now seen to be a pluralistic decade in which alternative art practices—performance art, earth art, video, poster-making, photography and so on—came to the fore. Critically the traditional arts of painting and sculpture received less notice; they seemed played out, exhausted.

Photography had the attraction of being a product of modern industrial society. It was a democratic medium, one which could be easily mastered to produce low cost, repeatable works. In addition, young artists who were not familiar with the work of previous photographers found its apparent lack of history to be liberating.

During the 1970s photography began to be taught in art schools in Melbourne, Sydney, Adelaide and Hobart; it was exposed through exhibitions in commercial galleries, particularly in Melbourne and at the Australian Centre for Photography in Sydney; and was frequently published in books and art magazines.

Art museums also began to form collections and exhibit photography. The Australian National Gallery's collection of contemporary Australian photography has grown around the gift of the Philip Morris Arts Grant, comprising over eight hundred photographs selected during the 1970s by James Mollison, Director of the Australian National Gallery. The exhibition Recent Australian Photography: from the Kodak Fund demonstrates the current vitality and diversity of Australian photography. It marks the continuation of certain well established photographic practices but also introduces interesting new approaches.

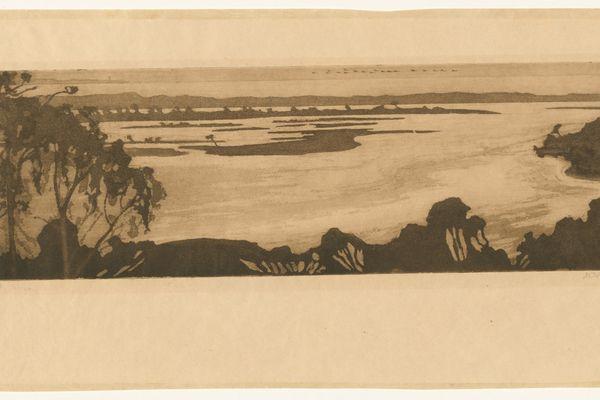

The traditions of 'straight' black and white photography are continued in Mark Johnson's Sydney beach scenes, Steven Lojewski's photographs of Sydney city buildings, and the finely printed landscapes of Melbourne photographers Ian Lobb and Les Walkling. Lobb and Walkling’s prints are small and intimate in scale, made to be viewed closely. Walkling uses a large format camera with an 8 x 10 inch (20.3 x 25.4cm) negative to produce tightly woven images of extraordinary detail. Bill Henson makes extensive series of black and white photographs which together create an emotionally charged environment. The two photographs in the exhibition are taken from the larger series Untitled, 1980-82, which brings together enigmatic images of faces and gestures of people within a Melbourne crowd.

We speak of ‘straight’ black and white photographs when the artist’s intervention or handwork is not obvious. However, the photographs on display are the result of highly manipulative and individualistic printing styles. Henson’s prints, for instance, are distinguished by their use of soft focus and warm print colour. A new but not unexpected development, given its occurrence overseas, is the widespread use of colour processes. Type C photographs (printed from a colour negative) are more prevalent now than in the 1970s. Examples in the exhibition are Debra Phillips’ diptychs, and Merryle Johnson’s country show panoramas which build on the intimacy of the colour snapshot.

Cibachrome photographs (printed from a colour transparency) have also appeared. In the past, the cibachrome process was dismissed for its plastic high gloss surface and artificial colours, whereas it is now embraced for these very high qualities and used to great effect by Julie Brown and Ken Heyes.

The exhibition features a large amount and range of manipulated work. Overt marking of the print surface was developed in the 1970s and has been continued by artists such as Warren Breninger who draws and paints on his photographs. Handcolouring, which was practised by many women artists from 1975 onwards, notably Micky Allan, has been carried on by Ruth Maddison, Miriam Stannage and Robyn Stacey. Stacey’s series Queensland – out west is softly coloured with dyes, an unobtrusive means of applying colour. The photographs describe the ordinary and undramatic and evoke the sense of place, not in a topographical way but as the generalized ‘feel’ of outback Australia.

Recently, handcolouring has been adopted as an end in itself, for frankly decorative effects. In Breakey’s Cactus pictures various media are used to romanticize and exaggerate her response to the subjects. Handcolouring is also practised by Allan Vizents and Fimo. Fimo’s photographs of a man explaining Yin Yang – with the aid of lamb chops and running shoes to form the ancient Chinese symbol – feature American photographer Duane Michals. It is a significant occurrence. Since the 1960s Michals has been a well known exponent of the stage-managed or constructed photograph which has emerged as a major new development in Australian photography of the last five years.

In the mid 1970s Carol Jerrems collaborated with her friends to produce such classic photographs as Vale Street, 1975, which we accept as being unposed, but which were actually 'set up'. In much current work we can no longer believe that the event photographed occurred naturally and therefore we do not accept it as being 'real' or ‘true’.

Photographers are making obvious their construction and control of the scenes being photographed. Taking cinema as the starting point, they now construct the stage and direct the action of their actors, who are often friends. The images are then brought together to tell a story. Ken Heyes' From a shipwreck is a fantasy piece, while Anne MacDonald's The knife is concerned with sexual violence against women. The sixteen photographs which make up her construction are framed in blood red.

In an equally political application of photography, Julie Brown deals with the depictions of women in art in her two big works from the installation Persona and Shadow. She uses herself to enact various stereotypes, for example, of the anxious pubescent girl from Edvard Munch's painting Puberty, 1894.

Other works, while less overtly political, explore the nature of photographic representation. The arrangement of photographs into various groupings – diptychs, panoramas, large scale constructions and series – serves to disrupt our assumptions about the single photograph being a mirror or ‘true’ reflection of the world. For example, Debra Phillips’ diptychs present the same scene from different viewpoints – which is true? In David Stephenson’s construction Self-portrait, Mount Wellington, the rock formations depicted do not line up across the fifteen photographs. The seams are visible reminding us that any form of photographic representation is always a construction.

One of the most conspicuous features of the exhibition is the large size of some works. They are public pieces, made to be seen in art museums, not homes. This parallels the developments in contemporary paintings and prints. It should be noted, however, that large scale photographic pieces have been a feature of Australian photography for at least a decade. A number of these will be featured in the forthcoming exhibition Big Pictures: Australian Photography 1975-1985 at the University Drill Hall Gallery from 5 March to 4 May 1986.

Recent Australian Photography: from the Kodak Fund brings together work by photographers from all over Australia. Sydney and Hobart particularly, and Melbourne, Adelaide and Perth, are very active areas. The diversity of work on display embodies an energy and confidence which it is hoped will continue into the future.