Soft but True

John Kauffmann, Art Photographer

22 Jun 1996 – 11 Aug 1996

John Kauffmann, The butterfly, c. 1930-35, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, Purchased 1980.

Exhibition Catalouge Essay

John Kauffmann was one of the most distinguished Australian exponents of the style of art photography known as Pictorialism.

Born in Adelaide, he spent a decade in Europe (1887—97) where he devoted himself to studying the new theory and practice of art photography. On his return to Adelaide, he began exhibiting. Throughout the next thirty years, he continued to make his graceful and soft-focus urban and landscape studies — his homage to the beauty he believed existed when the banal aspects of a subject were transcended into a harmonious ideal. He moved to Melbourne in 1909, and later established a professional studio there. In the 1920s, he did some commercial advertising work and provided illustrations for magazines such as Table Talk and The Home. His primary activity, however, was as an exhibiting art photographer. A monograph of his work — The Art of John Kauffmann — was published in 1919.

Kauffmann died in 1942, aggrieved that his role as a pioneer art photographer had not been better acknowledged and that his cherished aesthetic was no longer valued. In his lifetime most art museums did not accept photography as art. It is thus fortunate for this nation's heritage that a substantial proportion of the prints in his studio at the time of his death survived and entered the collection of the National Gallery of Australia in 1980.

This first retrospective of John Kauffmann's work provides an opportunity to view photographs which ascribe to a belief that to be soft was also to be true to the ideal. Works by some of Kauffmann's Australian and international contemporaries in photography and traditional fine art mediums are also included, placing his art photography in context. The National Gallery of Australia's collection of works by Kauffmann has been supplemented by loans from private collections.

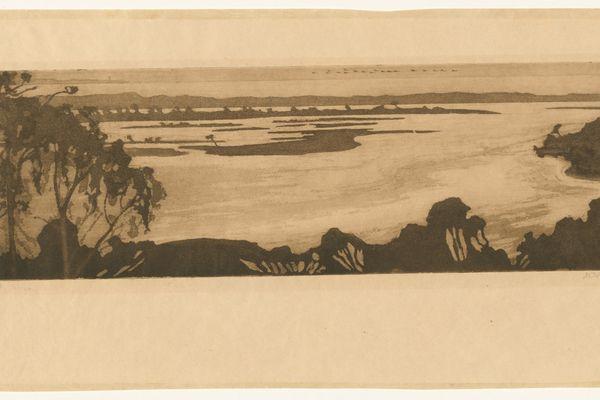

The Pictorialist style that Kauffmann absorbed in Europe in the 1890s was seen as a form of impressionism, but was also known derisively as the 'fuzzy-wuzzy' school, due to its preference for sombre, atmospheric imagery. It was a matter of pride to Pictorialists that their works were often confused with graphic art mezzotint prints, due to their manipulation of images by various printing processes. Pictorialists championed the greater truth of imagination and creativity over the factual world which, in their view, ordinary, sharp-focus photographs represented. By the late 1920s however, a new and younger generation of modernists was disputing Pictorialism's emphasis on the ideal and the beautiful. They banished the hazy outlines and veiled atmosphere of Pictorialism in favour of sharp, textured details, geometric forms, clear angles and outlines, and dramatic lighting. In the 1930s Kauffmann responded to the new interest in design and abstraction with a series of floral studies, but retained a softness and beauty in his prints.

Kauffmann's photographs seek out a world which is revealed in glimpses of soft, shadowy scenes. There is an intimacy with the subjects depicted, but the decisive moments or emotional revelations favoured by modern photojournalism are not present. The grand panorama and the complex saga of cities and settlement are absent from Kauffmann's work. People, if present, often have their backs to the camera, or seem absorbed in themselves and the setting. The only objects he approaches closely are flowers and plants, and even these have a curious dignity and independence despite the close-up focus.

This exhibition provides opportunities for between Kauffmann's works and those of other Pictorial photographers, particularly in their treatment of the city as a mysterious, atmospheric, magical place glimpsed through mist and shafts of light. Other works — such as those by Olive Cotton and Edward Weston — show the new, modernist taste for bolder design and intense scrutiny which succeeded Pictorialism.

Techniques

Pictorial photographers employed a variety of processes to alter the tonal range and details recorded on their original negatives. Mostly these 'control processes' as they were known, suppressed detail and gave an overall tonality which could be dark and atmospheric but also emphasised selected dominant highlights.

The lighting in Pictorial photographs presented scenes as if viewed through a veil of atmosphere; chiffon or other similar material was often interposed between negative and print to soften the contrast and outlines. Sometimes Pictorial photographers simply chose a subject already transformed by twilight or atmosphere. Soft-focus lenses could be used in making the negative or in the enlarger, or lenses might not be fully focused for resolution of the image. Special development of the negative could further romanticise the image. Finally, many different printing processes could be used to provide additional colour, textures and tones.

Critics of Pictorialism complained that these images were so greatly manipulated from their original subject matter that they were 'faked' — but Kauffmann insisted that he 'got everything in the negative', meaning that bad composition and inept exposure could not be improved by using control processes. However, to achieve his desired diffusion of sharp detail in the negative, Kauffmann exposed the negative or print through silk or cellophane and employed a soft-focus lens. After the introduction of panchromatic film, he used diffusing screens. He also used paper negatives to produce more graphic, less detailed images. These were made by contacting a print or negative with a second piece of oiled or translucent photographic paper resulting in a loss of sharpness and tonal range. He made both bromide and carbon prints, but is not known to have adopted oil, bromoil prints, gum bichromate other control processes popular with Pictorialists. A huge range of papers was marketed from 1900—20 appears to cater for the taste for matte images with different textures and qualities. It seems that Kauffmann did not use the more exotic surfaces available — his prints are usually matte, or have a soft, pearly lustre, and occasionally he printed on tissue.

Kauffmann also rubbed oil pigment into his prints to give them extra lustre and tone (his formula for the sea-green colour he sometimes used was a closely or guarded secret). He deftly selected which part of the image would be softer than another, but also to have increased the highlights or dark tones by applying pigment or a photographic retouching medium to either his prints or negatives. Handwork was done using scalpels; Kauffmann's handwork is apparent, although it rarely appears on the actual surface of his prints, implying that the final print was made from an earlier manipulated print or negative. His completed prints are distinctive for their quality and subtle luminosity. They also exhibit complex changes of focus within the one image, and often have a very shallow depth of field. He made relatively few extreme 'fuzzy-wuzzies'. Throughout his career, he reprinted old negatives, going back to his first studies in Europe. Winter mist c.1895, a work which attracted considerable attention at the turn of the century, was among the most frequently reprinted of his images. Pictorialism was an idealising style; the specifics of where and when a work was made were seen as irrelevant to the timeless beauties of art.

Museums place a higher value on 'vintage' prints, ie. those made close to the date of the negative. At each stage of production, Kauffmann's technique is more complex than it first appears. It would prove difficult to match now, due to the changes in commercially available chemicals and papers over the years.

Glossary

Gelatin silver photograph is a museum cataloguing term for the most common form of black and white prints first marketed commercially in the 1890s but predominant after World War I. They were so named because grains of light-sensitive silver are suspended in a transparent layer of gelatin. The gelatin papers were cheaper to produce than the albumen (ie. eggwhite) coated papers of the nineteenth century, and developed quickly (they were especially suited to electric light enlargers).

Bromide, chloro bromide were terms used from the 1890s onwards. Until well into the 1950s, art photographers used a variety of matte bromide cream stock papers which developed up to give brown tones. Highly glossy photographs in 'cold' blue—black tones on white paper were first introduced in the 1910s. These were more suitable for reproduction in the new illustrated magazines and books which used the half tone process. From the 1920s this type of glossy surface became the norm for black and white photography and exhibition work.

Carbon print was an attractive print process in which sheets of commercially produced pigmented tissues in a range of rich colours — brown, black, green, red and blue) could be sensitised to take an impression by direct contact with a negative or photographic print under sunlight. The result was permanent. This process was popular with art photographers for its fidelity to the camera's capacity for detail and tonal range, while also having the surface quality and colour of traditional graphic art prints. Carbon prints were also convenient for amateurs, as prints could be made without electric light enlargers or photochemical development. They were also called 'carbro prints' when made from prints rather than negatives.

Gum bichromate, oil and bromoil prints were the main 'control processes' used by serious art photographers around 1900—20. They were deployed as an assertion of the photographers' freedom to introduce any expressive Pictorial elements they deemed appropriate in creating an autonomous work of art with the camera. The entire original photographic image could be altered in colour and tone by increasing dark and light tones. Unwanted details could be obliterated or other elements drawn in. The resulting surface was permanent.

Gael Newton

Curator of Australian Photography, National Gallery of Australia

Touring Dates & Venues

1996–1997

- Bendigo Art gallery, Bendigo, VIC

11 Sep 1996 – 3 Nov 1996 - Art Gallery of New South Wales, NSW

4 Dec 1996 – 27 Jan 1997 - Art Gallery of South Australia, SA

14 Mar 1997 – 27 Apr 1997 - Museum of Modern Art at Heide, VIC

3 Jun 1997 – 13 Jul 1997 - Bathurst Regional Art Gallery, NSW

18 Jul 1997 – 31 Aug 1997 - Toowoomba Regional Art Gallery, QLD

19 Sep 1997 – 2 Nov 1997