The Birth of the Modern Poster

10 Feb – 13 May 2007

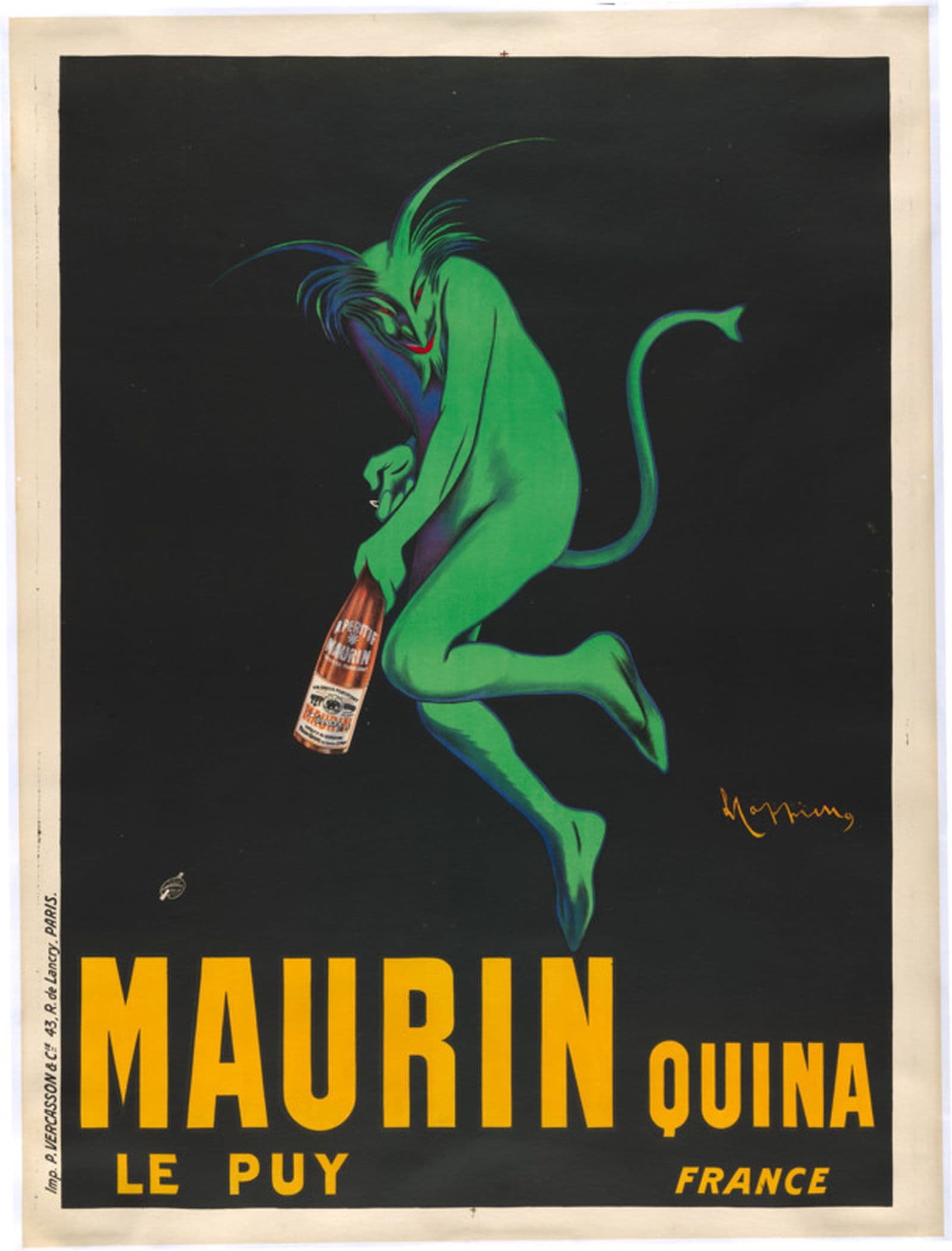

Leonetto Cappiello, Maurin Quina, 1906, The Poynton Bequest 2005

About

The Birth of the Modern Poster will examine poster art and its evolution from the late 19th century to the early 20th century [approximately 1885 – 1915] and will draw exclusively from the National Gallery’s Collection of International Posters.

Exhibition Pamphlet Essay

Born in 1836, Jules Chéret is widely regarded as the ‘father’ of the modern poster. Chéret began studying lithography at the age of thirteen and at sixteen was taking classes at the Ecole Nationale de Dessin [National School of Art] in Paris. He made his first black-and-white posters in 1855 and from 1859 to 1866 studied colour lithography in London. It was largely through Chéret that lithography, which had fallen into disrepute among artists of the mid nineteenth century, was revived in the 1890s in a spectacular renaissance that would become known as the ‘colour revolution’. Without lithography, and without Chéret, posters as we know them would simply not exist.

In addition to being a technical innovator, Chéret was a poster designer of great genius, producing more than 1000 of them over his very long career. Among his most well known works are the posters he designed for the famous Moulin Rouge in Paris (including the posters advertising its opening in 1889) and for the Folies Bergère. In 1893 the American dancer Loïe Fuller made her debut at the Folies and commissioned Chéret to design the posters to advertise the event. These, and the subsequent designs he did for her, were to become some of Chéret’s most famous and best-loved works.

Fuller’s repertoire at the Folies Bergère comprised four dances: the Serpent Dance, the Violet Dance, the Butterfly Dance and the White Dance. Each had its own lighting and Chéret’s poster, Folies-Bergère: la Loïe Fuller 1897, perfectly captures the mood of diaphanous light and swirling movement of Fuller’s performances, and is rightly considered one of the masterpieces of the form.

While Chéret produced posters for a wide variety of contexts – for publishers, milliners, entertainments and to advertise lamp oil – he did so using a very limited range of figurative forms. His posters invariably feature a ‘chérette’ – a pretty, blond, rosebud-lipped young woman whose association with the product she advertises is, as is often still the case, tenuous at best. Today, Chéret’s generic, cartoon-like women strike our modern sensibilities as cloyingly sentimental, adolescent and naively saccharine. Despite this, his posters have an undeniable presence, a sense of flamboyant energy that is uniquely, identifiably his own.

Indeed, without Chéret we would not have Pierre Bonnard as a poster artist – the debt to Chéret of Bonnard’s first poster, France-Champagne 1891, for example, is obvious. And without Bonnard, we would not have the poster masterpieces of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. While only ever producing approximately thirty posters in the period 1891–1901, Toulouse-Lautrec’s works are some of the most brilliant in the medium. They are also vastly more human than Chéret’s work. Toulouse-Lautrec’s poster of Jane Avril (a dancer at the Moulin Rouge), for example, while displaying the sense of caricature common to much of his work, has about it an indisputable aura of individuated character.

We have the impression that this is Jane Avril dancing, Toulouse-Lautrec perfectly capturing, in a work of considerable compositional sophistication, her coquettish, mid-stepped, black-stockinged sensuality. And yet the barely articulated features of her face reveal an underlying melancholy. Avril, who was in fact small, pale and unusually shy, was one of Toulouse-Lautrec’s great friends and Jane Avril, his homage to her, was his penultimate poster. He would produce only one other poster, in 1900, and die in 1901.

For all of Chéret’s technical brilliance, his flamboyant use of colour and the formal eloquence of his work, the women in his posters, as indicated above, remain ciphers, mere empty reflections of the false and superficial gaiety of fin-de-siècle Paris. Chéret was imprisoned by a view of women that was the product of a particular historical mind-set. By way of comparison, one only has to look at Toulouse-Lautrec’s poster La passagère du 54 – promenade en yacht 1896 to see what real, human insight is. On a cruise he undertook in 1895 in France from Le Havre to Bordeaux, Toulouse-Lautrec became infatuated with the beautiful young occupant of cabin 54, so much so that he refused to get off at Bordeaux despite the exhortations of his friends. Instead, he sailed on to Lisbon, Portugal, hoping all the while – but failing – to be introduced to her. La passagère du 54, which advertised the Salon des Cent exhibition of 1896, recalls this incident. It shows us the partially obscured object of the artist’s desire. She is neither particularly attractive nor young, and sits, prosaically, in a deckchair; serenely absent and quietly oblivious to Toulouse-Lautrec’s tortured longing, his crippled inability to approach her. In a work of supreme, self-ironic understatement, Toulouse-Lautrec documents for us all our own idiosyncratic perceptions of beauty, our failures of courage, our nostalgia for opportunities missed, for futures untold, irretrievably lost.

The other great artist of the 1890s to feature women as an integral part of his poster designs was Alphonse Mucha. Born in Moravia in 1860, Mucha moved to Paris in his twenties and went on to become one of the greatest exponents of the Art Nouveau style, of which Job 1894 is a superb example. Job displays all of Mucha’s trademark symbols and design characteristics. The poster, which advertises Job cigarette papers, shows a woman sensually involved in the act of smoking. Although ‘respectable’ women did not smoke at the turn of the century, there was a popular custom in France of linking l’amour, le vin et le tabac [love, wine and tobacco] and of using images of women to advertise tobacco in order to give the product a sense of illicit glamour.

In Job, Mucha’s extravagantly stylised depiction of hair, known at the time as macaroni or vermicelli, served as an essential decorative component while also reinforcing the sensuousness and eroticism of the woman and therefore the poster. Closer examination of Job, however, reveals several coded sexual references, such as the curled up toe that peeps from beneath the woman’s flowing gown – a symbol of female sexual arousal – and the raised tip of her cigarette. Job intentionally pursues a subliminal link between cigarettes and oral fixation; circles and aureoles featured in all of Mucha’s designs. A detail often overlooked in the poster is the repeated use of the interconnected letters spelling out the name Job. The brand name Job developed from the initials of the French craftsman Jean Bardou who invented the idea of a booklet of rolling papers made from rice paper. Originally the initials ‘JB’ were separated by a diamond, and as the brand grew in popularity people began to refer to it as Job. In the poster Mucha uses the letters as the background pattern, as well as in the shape of the clasp which holds the woman’s dress together, drawing the eye to her breasts. Job exemplifies a very identifiable characteristic of Mucha’s work: what at first appears to be a rather sweet and innocent image is, in fact, a very sexually charged one.

Of a completely different order to Chéret, Mucha or Toulouse-Lautrec is the work of Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen. Born in Lausanne, Switzerland, in 1859, Steinlen moved to Montmartre, Paris, when he was twenty-one and stayed there for the rest of his life. He had initially studied philosophy and literature, and this informed many of his depictions of the everyday life of Montmartre. Like the work of Honoré Daumier, much of Steinlen’s art is concerned with the underlying social realities of the day. He was an overtly political artist and had a great sympathy for the ‘social-realist’ works of the writer Emile Zola. In 1900 he produced the monumentally sized advertisement for the stage adaptation of Zola’s novel L’assommoir [The low dive]. The design is deceptively brilliant – it is a poster within a poster. In the foreground we see Gervaise and Coupeau, the two main protagonists of the play, and behind them, on the wall, is a billboard advertising the play itself – its tous les soirs à partir du 1er Novembre 1900 [Every evening from the 1st of November 1900] conveying both a sense of immediacy and a paradoxical historical distancing.

Similarly, Steinlen’s huge poster Le locataire [The tenant] of 1913, with its sombre, low-key, unglamorous text which simply states, ‘Appearing on 1 October against the privileges of landlords “The Tenant”, a publication of the Union of Tenants under the direction of G. Cochon’, has a sense of immediacy that is reinforced by Steinlen’s depiction of the desperate poverty and despair of the working classes in turn-of-the-century Paris.

With the start of the twentieth century, however, came a time of growing upheaval – social, political, economic and aesthetic. This upheaval found its expression in the many breakaway art movements which characterise the age, the most significant being the Secessionists in Germany and Austria. With these movements came a new, if short-lived, idealism which was exemplified by the many references to Ancient Greece in the posters produced to advertise the exhibitions of the artists associated with them. In Franz von Stuck’s poster of 1897 advertising the Seventh International Art Exhibition in Munich, for example, he shows Athena, the multi-portfolio-ed goddess of wisdom, war and the arts and crafts, holding Nike, the goddess of victory, in one hand, and the staff of judgment in the other. A helmeted Athena – an image that reappears in Stuck’s poster advertising the Sixty-first Exhibition of the Vienna Secession in 1921 – looks on from the right-hand panel, while on the left we see the classically influenced emblem of the Künstler Genossenschaft [Artist’s Co-operative]. Similarly, Stuck’s poster advertising the Munich International Exhibition of 1913 features an Apollonian horse-drawn chariot. The message is clear: the tinsel-and-glitter fake gaiety of fin-de-siècle Paris is finished with, and a new, more rigorous, more ambitious and revolutionary age is being heralded – in Germany and Austria at least.

Back in France, however, the first decade of the twentieth century was to see its own revolution in poster design with the arrival in Paris in 1898 of the Italian-born Leonetto Cappiello. Cappiello’s work became so influential that he is often referred to as the ‘father’ of modern advertising. His revolutionary insight into the art, an insight which remains a staple of advertising today, was based on the psychological phenomenon of image association. He was the first to deliberately unite a product with an instantly recognisable icon or image. Thus, when a viewer saw the icon they remembered the product.

In Maurin Quina 1906, a poster advertising a French aperitif of the same name, Cappiello has depicted a devilish green figure sneakily uncorking a bottle of the advertised beverage while grinning at the viewer. It is said that there is a little devilry in any alcoholic drink and Cappiello became known for using infernal imagery in a number of his liquor-advertising posters. In Maurin Quina the cheeky green sprite recalls the nickname and effects of that most infamous beverage of the Belle Époque, la fée verte [the green fairy] or absinthe.

Cappiello was also the first poster artist to realise that modern transport had fundamentally changed the way people perceived the visual world and that something fleetingly seen while in transit could be used in an associative way. Having registered and deciphered an image close up – as a pedestrian might – the advertising message and product could be instantly re-invoked by the mere glimpse of the image from a moving bus or train, hence his use of bright and easily recognisable forms and colours. Maurin Quina is Cappiello’s most famous poster. It is also the finest example of his manipulation of brand identity, and of his adaptation of poster art to meet the demands of a new and modern era.

Cappiello’s work was continually evolving – see, for example, the re-emergence of the ‘devil’ motif in his beautifully stylised Becuwe poster of 1927. This poster echoes in its modernity the work of another artist included in this exhibition, that of the American born, London-based E. McKnight Kauffer. His Soaring to success! Daily Herald – the early bird of 1919, with its flock of birds in the extreme upper reaches of the picture plane, seemed, at the time, and perhaps it still does today, to embody something quintessentially modern about the age. It was an image, like many of the images in the posters on display here, that would have a long advertising shelf-life. The remarkable thing about it, however, is that when we compare it to a work by Chéret, such as Folies-Bergère: la Loïe Fuller which was made little more than twenty years earlier, we seem to be looking back across an historical abyss. On one side we have an age of trivial innocence; on the other we have the beginnings of a vastly more complex, modern era, the aspirations of which, in defiance of the cataclysms of the First World War, Soaring to success! seems no less innocently to articulate.

There are many other fine examples of the emerging art of advertising in this exhibition, from Jean Carlu’s famous poster advertising Peugeot bicycles, which he designed as a young man in 1922 before embracing the geometric abstraction for which he would become famous; Jean Cocteau’s monumental homage to the Russian ballet dancer Vaslav Nijinsky of 1911; John Hassall’s brilliant, fat-man, comic-ironic take on Chéret’s dancing figures, Skegness is SO bracing 1908, which became one of the most successful advertising posters ever; and the simpler, yet equally memorable, images published by the British Parliamentary Recruiting Committee in support of the First World War effort.

Birth of the modern poster takes us, then, on a journey from one age to another, with each of the more than forty works in the exhibition, all originally conceived as ephemeral posters, representing a step along the way. The exhibition is the precursor to a much larger show scheduled for 2010 at the National Gallery of Australia which will be devoted to the last 100 hundred years of the art of the poster.

Mark Henshaw

Curator, International Prints, Drawings and Illustrated Books

Simeran Maxwell

Intern, International Prints, Drawings and Illustrated Books