Between the Bush and Boudoir

8 Jun – 22 Sep 1996

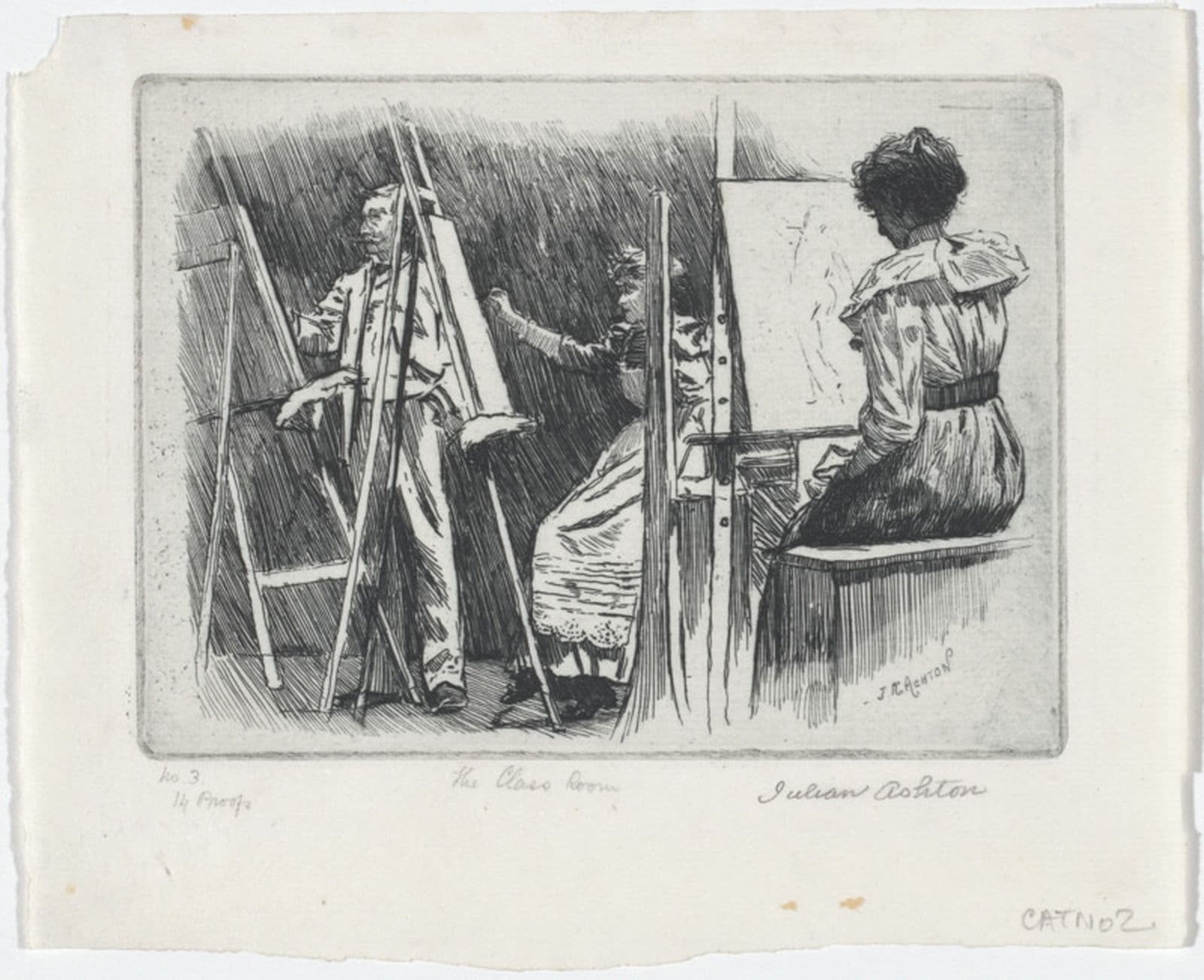

Julian Ashton, Angus & Robertson Ltd., The class room., 1893, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, Purchased 1987.

Curatorial Essay

The Australian impressionists represented in Between the Bush and the Boudoir — Julian Ashton, Charles Conder, Emanuel Phillips Fox, Frederick McCubbin, Girolamo Nerli, Tom Roberts and John Russell — emerged during the 1880s, as part of a new generation of Australian artists. Most of these seven artists do not qualify as exclusively Australian in their training and careers, as they studied and spent many years in Europe. The sole exception was Frederick McCubbin, who only visited England and France briefly in 1907. In their practice of looking beyond their own country for inspiration and training, the impressionists were similar to many Australian artists before and since.

This group embraced an approach to painting that was informal and direct, unstructured and relaxed; and these qualities made their work famous as the first genuine representations of an Australian way of life. The approach, however, was informed by the European plein-air painting tradition, popular in the last decades of the nineteenth century.

A plein-air painting was one that was painted outdoors, and strongly influenced by light and atmosphere. The plein-airists took their palettes, paints, canvases, stools and easels into the landscape. In principle the impression was seen, painted and completed in one session, although in practice revisions were made. The concept was revolutionary — the traditional standard of achievement in the arts and sciences had been a definitive statement. According to that standard the 'last word' in visual expression would be a more considered, structured and planned work than the impressionists' 'first thoughts'. The difference between the traditional considered statement and the casual impression so ardently pursued by the artists of the late nineteenth century is represented by Koort Koort-nong 1860 by Eugene von Guérard and Conder's Impressionists' camp 1889. As can be imagined, the impressionists were greatly criticised by those who valued a definitive statement.

In France, where Impressionism had great impact, its influence was evident across the arts — in Emile Zola's prose style, in the fluid structure of musical composition (by Debussy and others), and in the paintings of Monet and his contemporaries. It was a style that challenged and eventually prevailed over the academic principle of the complete statement. By the time the Australian style appeared in the 1880s, French Impressionism had shifted direction and fractured into various approaches. A large proportion of plein-air painters were considering the task of looking and recording in an almost scientific light; for some, an impression was similar to a snapshot view; others dwelt on the summary design; there were those who were exploring the suggestive poetry of first perceptions; and for yet another group, the psychology of what constituted a first impression was of paramount importance. These concerns — which highlight some of the implications of painting first Impressions — emerged in various ways in the works of the Australian impressionists.

In Australia, impressionism had its own character, defined by the circumstances in which it developed. This exhibition explores how that character is reflected in the content and style of the paintings on display. Five themes are explored: Artists at home in the city; Leisure; an Australian bohemia; Working life in the bush; and a French comparison. (The British comparison has not been isolated for special attention in this exhibition.)

The impressionist leaders were a small group who camped out at Heidelberg in Melbourne from Christmas 1888 to April 1890. They and their friends were nicknamed the 'Heidelberg School'. Exhibitions and books about that famous School invariably focus on a vision of outdoor life 'under a southern sun'. Strong masculine labour is part of that story, alongside popular images of pretty young women in pink and children in bonnets in a summer landscape. The Heidelberg School has come to represent the nostalgia of a relaxed 'Golden Age' in Australia at the end of the nineteenth century. This exhibition ventures further into the art of the era. Beach scenes and picnics on blue and gold days were only part of the story — and not its most intriguing aspect.

Artists at home in the city

Impressions painted in and around the home, or representing the artist's daily life, are like pages from the artist's diary (and some of these works were presented to the public in that light).

Charles Conder painted Impressionists' camp on a Sunday in July 1889. He worked on it in the front room of the dilapidated Eaglemont homestead in Heidelberg, Melbourne, where he, Arthur Streeton and Tom Roberts regularly camped. On a scrap of paper, Conder sketched the bare and underprivileged reality of the impressionists' camp. As a finishing touch, he decorated the unpainted wall depicted in the work with a rectangle of blue and yellow — Streeton's oil sketch for Golden summer, Eaglemont. Conder was twenty years old at the time, and painted this interior for the 9 by 5 Impression Exhibition, held the following month. At this time, he painted a portrait of the thirty-three-year-old leader of the camp, Tom Roberts, labelling him 'An impressionist’.

The frame of Impressionists' camp’ is the original prepared and painted by Conder. Quite possibly these wide, wooden frames (mass-produced in a Melbourne timberyard for the artists) were an inexpensive, do-it-yourself of approximation of James McNeill Whistler's wide, flat frames; if so, they were a notably rough and ready version unlike the elegant Whistler frame.

This small painting of Ashton's wife standing by the fire in their London home is informal in style and intimate in subject. It exemplifies the Impressionist style Ashton absorbed while studying in Paris in 1873. It may have been intended as preparation for commercial work: with very slight modifications, the image was published in Cassells Family Magazine in March 1877, illustrating a story entitled ‘Faces in the Fire’.

Ladies' classes in life drawing, held by the Art Society of NSW through the 1880s, invariably failed to maintain sufficient numbers to pay for themselves. In October 1892, Ashton proposed holding a mixed life class. The morality of this arrangement was questioned. The issue arose again in May 1894, when Ashton reported to the Art Society Council that 'a lady [Nelly Drewe or Edith Deane] does attend the [men's] life class'. A separate life class was again enforced. Then, in August 1894, Lister Lister, a conservative member of the Art Society, objected to the ladies' life class being conducted by a male. Ashton suggested that the classes could be separated by a screen. In December, with the whole structure of the Art Society threatened by a faction of younger artists, Ashton once more proposed a mixed class, which was finally agreed to in February 1895.

When he painted Girl with bird at the King Street Bakery, Frederick McCubbin had recently obtained a secure position as drawing instructor at Melbourne's National Gallery School. He no longer had to work at the family bakery to help support his widowed mother and family. For those who knew the artist, the image told a story about his life at the time: the bakery is already in disuse, with dirt piled on its threshold and the bread tins are being used as flower pots at the oven's door. A schoolgirl is comfortably occupied in the leisurely pursuit of knitting or crochet. To those who did not know the artist's background, the image may have represented a slice of life in a poor city street. Nineteenth-century representations of city poverty had a suggestive iconography, in contrast to the healthy life of the country. In this image, poverty could be assessed not merely from the ragged curtain and cracked masonry, but also in the work's grey tonality, and its the depiction of the buildings and laneway, for which the artist used stain-like glazes and lumpy paint (with red colour underneath). In contrast to the dingy city however, the foliage — painted in fine detail and clear colour — has the verdant freshness of nature, and the girl's white pinafore strikes a similar note of purity. The painting has been constructed in the story-telling mode of academic painting, rather than taking the seemingly casual impressionist approach.

The murky attractions of Chinatown in Melbourne's Little Bourke Street were often written about in the 1880s. It was rumoured that the opium trade, white slave traffic and other criminal activities flourished in that quarter's shadowy depths. This fearsome reputation was matched by the appeal of its people with their exotic food and trade goods. Roberts cleverly presented his subject as a popular romance rather than dramatising it as a den of iniquity.

Julian Ashton had been employed as 'an illustrator of Australian places' for the Picturesque Atlas of Australasia and due to this experience was an expert at conveying his exact message in his work. In the 1880s, parliamentary debates, health reports and newspaper headlines cast the Rocks area of Sydney (shown in Old house, Trinity Lane 1893) as a slum, and the Woolloomooloo area of Hordern stairs as little better. Ashton, however, saw these districts as historic areas which were picturesque and appealing. The blue sky, foliage and dainty woman in Hordern stairs unequivocally refuted the rough and tumble image of Woolloomooloo.

Leisure

In the 1870s Marcus Clarke described the Australian bush as a scene of weird melancholy. His gloomy interpretation of a panoptic landscape in which people were irrelevant was widely discussed. The Australian impressionists, who were students at the time, opposed and overturned that bleak vision, appropriating the bush for pleasure. Turning the bush into a treasured place of leisure, they showed themselves and others camping, fishing, yachting and trail riding.

The outdoor life of boys only appears once in this exhibition, in McCubbin's The Yarra, Studley Park 1886. Otherwise, the theme of leisure is played out by adults, predominantly pretty young women in summer clothes. In two paintings by Conder, female figures are offset by a lone male in dark clothes. In Bronte Beach 1888, the male figure sprawls face down on the sand between two women. Herrick's Blossoms 1888 had a forthright message: the blossoming of youth paralleled the bursting forth of new life. The mention of Robert Herrick's bittersweet poem 'To Blossoms' in the painting's title would also remind viewers that youth was fleeting — the end of life was death. Conder painted this work in the orchard of a Griffith farm, near Richmond on the Hawkesbury River. He was staying at the farm for a few weeks, with a group of other young Sydney artists. They all painted images of spring and courting. For Conder, the impressionist style could be poetic: impressions could create moods, thoughts and sensations. His The path from the woods 1890 is as threatening, sombre and wintry as Bronte beach is full of light and summer.

Some of Ashton's most attractive homages to young women were painted when he was of grandfatherly 'age, suffering from impaired vision, and the highly respected head of a private art school in Sydney. The student, Tuggerah Lakes 1915 appears to be as conventional as a holiday postcard. The model's kimono-like summer wrap sets the painting's colour note; the garment's flimsy texture and pattern establishes the Japanese aspects of the painting also. When Ashton painted this work, impressionism had ceased, for many, to be a style of genuine exploration or a means of expressing real content; by 1915 it had instead become an attractive formula.

An Australian bohemia

Ashton's Bathers 1914 was a famous painting which hung for decades in the Sydney Art School, without a whisper of scandal attaching to Ashton or the institution. We may assume that the image was assembled artificially from studies completed in the studio, rather than depicting posed nudes on location. A fundamental question has to be raised about Bathers: Does it have the meaningful content that is an essential component of art, or is it merely an art school exercise?

McCubbin's Self portrait c.1908, in which the artist wears a beret, is modest in facial expression and quiet in tonality; but the subject, posed after the formidable example of Rembrandt, declares his creative ambitions. Isolation from Europe gave McCubbin the freedom to paint such a self portrait.

An eastern princess, painted by Tom Roberts in Sydney in 1893, portrays a well-known nineteenth-century type of femme fatale. Alien, dark-eyed and physically strong, this creature was seductive and simultaneously threatening the exotic opposite of the well-bred female ideal Roberts had often portrayed. The model was Lena Brasch, the eighteen-year-old sister of the artist's host at Curlew Camp on Sirius Cove. It was Roberts's second attempt at painting Lena. He focuses on his subject's face, veiling her body in plain, diaphanous drapery, and dramatically dividing the face by portraying one side in shadow. When painted earlier by Roberts, Lena appears in an uncomplicated, everyday aspect in the Portrait study of Lena Brasch c. 1893. Throughout the 1880s and 1890s Girolamo Nerli, a well-born Italian, made extended visits to Australia, living in various cities and towns. He came to know Australians very well, assessing their tastes from his own teasing, cosmopolitan point of view. In A Bacchanalian orgy 1888, he gave Australia an exuberant orgy, redolent with the vulgarity that Victorian Australians both loved, and loved to condemn.

Nerli produced six or more 'orgies', all flashily painted and similar to each other, of which the National Gallery of Australia's A Bacchanalian orgy is the biggest and most spectacular. The image is indebted to Giovanni Muzzioli's oil painting, The temple of Bacchus 1873 (Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Moderna, Rome); however the banana tree and gravel courtyard in Nerli's work were sufficient to locate the scene in the Pacific. At the time it was made, viewers of the painting were divided between the incoherence of the image — which is most noticeable in the awkward dislocations of space and strangely distorted figures — and admiration for Nerli's brilliant painterly effects.

Working life in the bush

To Australian colonists, drought, fire, flood, isolation and death by starvation in the bush were burdens to be endured, rather than battles to be fought. One of the most striking contrasts between Australian colonial culture and American frontier culture was that, in Australia, the bush was not predominantly thought of as a zone of moral challenge, but rather a scene of endurance and partial adaptation.

Those expecting colonial frontier images of male valour and feminine gentility may be surprised by Ashton's Bridget Widdowson at Cawnpore 1872, whose subject is depicted holding a group of prisoners at swordpoint. However, other factors are at play in this work: it portrays an image of life in India, rather than the Australian colonies; and it was made as an illustration for a story (untraced), rather than as the artist's considered statement on the roles of the sexes in the colonies.

Although the impressionist style depicted 'feminine' aspects of Australian country life, this was achieved in a different way from Ashton's depiction of the full-breasted, Boadicea-like Bridget. In impressionist works, the bush became a domesticated territory of picnics, bathing parties and small-scale suburban farming, and the aesthetic territory of art. In these works, the closest the bush ever came to having the edgy masculine power of the frontier was in images of drought and storm, for example, Roberts's small cloud study, Storm c.1899.

As its title suggests, Conder's Under a southern sun 1890 had a national theme, but was definitely not a traditional pioneering image. The site depicted by Conder was the subdivided, pegged-out grounds of Eaglemont. Although prepared for sale at the end of the 1880s, the housing lots remained unsold in the depression of the late nineteenth century. There may be an element of irony in Conder's image — 'pioneering' in Australia in 1890 was more likely to be the struggle of an unemployed man to provide shelter and a living for his family, in country that was already settled.

We know the date and almost the exact hour of the early morning on which McCubbin discovered the subject of Hauling rails for a fence, Mount Macedon 1910, from a postscript and thumbnail sketch the artist included in a letter to Tom Roberts. It was 19 January 1910, at Fontainebleau, Mount Macedon. McCubbin wrote, 'I think I have just got a ripping subject to paint, morning sunlight, Hauling rails for a fence, a regular Millet. I have made a number of poshards [a pochade was a small composition sketch] ... I wish you were up here, the air of the Mountain is lovely.' J.S MacDonald (the artist's first biographer) recorded that McCubbin, when in search of that imaginative rapport 'never penetrated far into the bush, seldom beyond cooee of some dwelling ... [and] his vehicle was the dray or wood cart of his time and place.'

A French comparison

Like most artists, E. Phillips Fox regarded Paris as the centre of art. He studied in France in the late 1880s, and maintained Parisian standards during his subsequent years in Melbourne. Returning to France in the early 1900s, he updated those ideals. Autumn glow, Charterisville c. 1899 and Moonlight on the Yarra River 1900, painted towards the end of his first term in Australia, were faithful to the concept of recording an impression of a subject's dominant colour effect and the pattern of a scene in nature. McCubbin's Winter landscape sketch c. 1897, arose from the different ambition of perceiving the grandeur of human endeavour in ordinary, earthbound realities. McCubbin was inspired by the French painters, Corot, Jules Bastien-Lepage and Millet.

John Russell spent most of his adult life in Europe, living in France from the mid-1880s until after World War l. Russell's art, like Fox's, was driven by explorations relating to technique as much as to perception. From the south of France in the summer of 1890—91, when painting In the morning: Alpes Maritimes from Antibes, Russell wrote to Tom Roberts: '…for the past two years [I have] been chasing colour … Pure or as nearly pure as possible. Colors [sic] draped loosely over one t'other — cobwebs.' On this canvas, which he began working on around December 1890, he first used his brush to outline the composition in alizarin. Using long hogs-hair brushes, he then worked right across the canvas, blocking in large areas of colour — the beginning of his coloured 'cobweb'. He waited for the paint to dry, then framed the work (so as to consider the total decorative effect) and worked on, within the frame, applying a second, and probably a third, layer of paint.

This method of painting was not direct, 'all-in-one-sitting' impressionism, as it involved waiting for one layer of paint to dry before working on the canvas again. But, in a letter to Tom Roberts, Russell defended his practice as French Impressionism: 'As understood here [in Paris] it consists not of hasty sketches but in finished work in which the painting of colour and intention is kept. Monet for instance will put 10 or 12 sittings on a canvas.'

Paris, which turned Fox and Russell to thoughts of technique and colour, gave Conder a bohemian way of life. Unlike Toulouse-Lautrec, one of his companions during nights at the Moulin Rouge, Conder was not inspired to record the scenes he saw. Rather, the allusive material of his erotic 'fantasies' lay in the rococo period and the boudoir scenes of Balzac and Boucher.

Mary Eagle

Senior Curator of Australian Art, National Gallery of Australia