Flash Pictures by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Artists

21 Dec 1991 – 8 Mar 1992

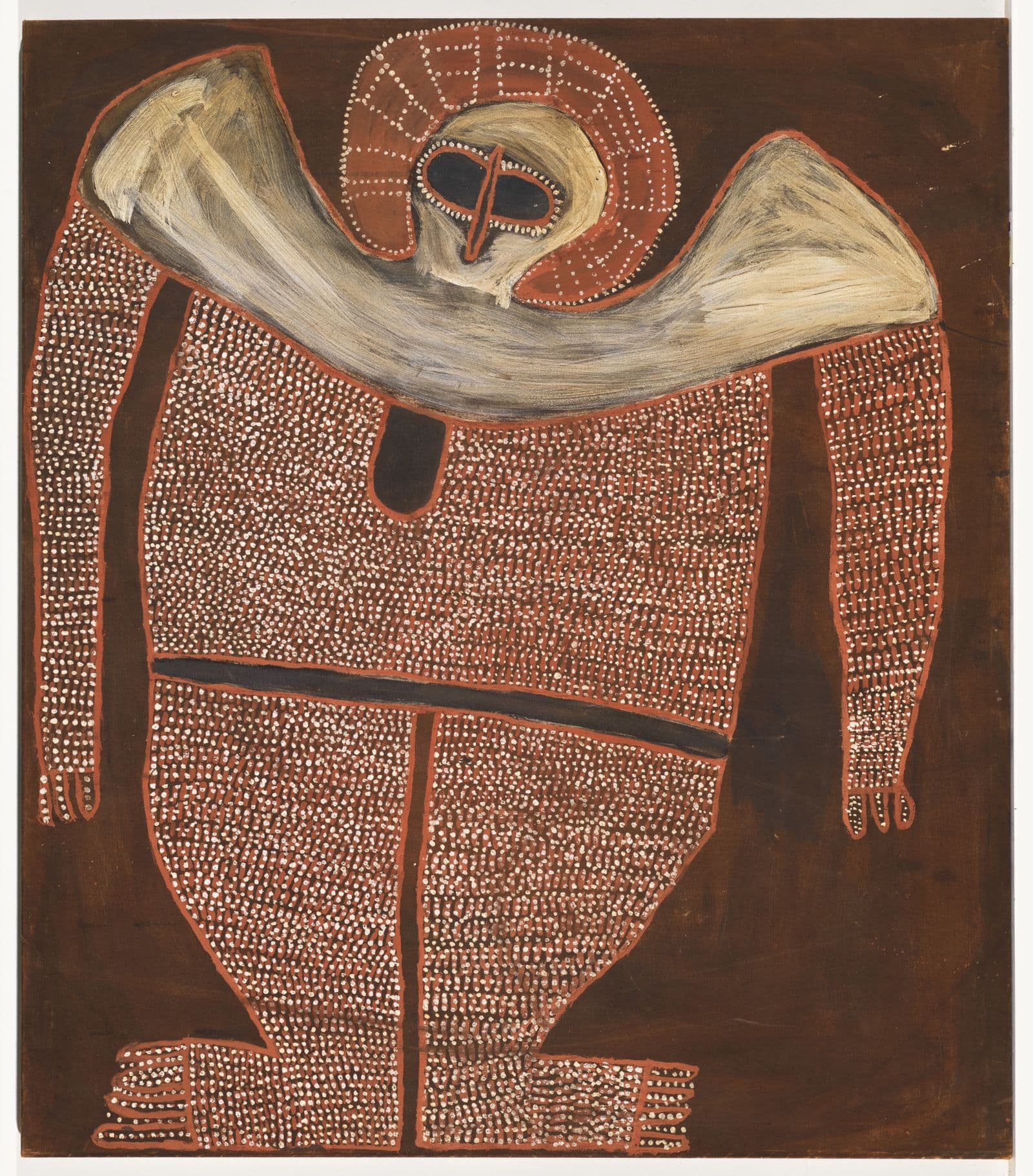

Alec Mingelmanganu, Wunambal people, Wandjina, c.1980, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, Purchased 1990. © the estate of the artist, licensed by Aboriginal Artists Agency Ltd.

About

"This stone is called Tjangala, just like me. I look after this stone— he's my grandfather… I'll tell you the Dreaming for this Tjangala, how he came here, poor thing", and although the stone is like nothing in the landscape — its smoothness, its deep brown half-shine, its weight, the sound it makes when tapped, giving it the atmosphere of something alien or supernatural — Paddy halts for a second. Leaning forward he dips his finger into some red ochre and paints one rough finger-width stroke across the stone. There's a shadow of a smile across his face, maybe from pleasure, maybe from a private joke. He turns and says… "Oh, make 'im flash, poor bugger”. [1]

With that mark in red paint, the artist Paddy Tjangala transformed an apparently mundane object into something of meaning on another plane.

The term 'flash' is used among Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people to indicate a notion of showiness and sparkle, something which sets things apart from the ordinary, something which is visually arresting and stimulating. The exhibition Flash Pictures by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Artists is an opportunity, perhaps the excuse, to assemble paintings and painted objects which are exceptional in exhibiting a blatant appeal to the senses — works which show bravura in their execution, works demonstrating a virtuosity beyond the usual production, or perhaps works that are just bold and cheeky — in short, works that are flash.

Flash is not a school or a movement. The exhibition brings together an extremely varied group of artists, men and women, young and old, experienced hands and emerging artists, those from the country, the suburbs, the city, all over Aboriginal Australia, using traditional and non-traditional materials. However, the works in the exhibition are displayed according to their visual and pictorial connections rather than along the lines of the area of origin.

The content on this page is sourced from: Wallace, Daphne, Michael Desmond, and Wally Caruana. Flash Pictures by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Artists. Canberra: Australian National Gallery, 1991.

Essay

The ability for paint and painted designs to take an object out of the ordinary by endowing it with another presence accords with traditional ceremonial ways; in ritual an object is painted with designs to imbue it with ancestral power or, through the act of painting the body, a dancer assumes the presence of an ancestor. In central and eastern Arnhem Land an artist takes a bark painting from a dull state to one of brightness through the use of cross-hatching and in particular through the use of white pigment. The painting becomes a shimmering object, evoking the presence and power of the creator beings.2 The designs and images do not merely represent or decorate another entity — it becomes, through the application of paint, a part of the continuum that embodies the totality of the religious experience.

In Niwuda, Yirritja honey, 1986, by Jimmy Wululu, and Wakuthi Marawili's Fire Dreaming with dugong hunting story, 1982, the finely painted diamond patterns refer to honey in the former case, and fire and flowing water in the latter. Both designs are used in ceremonial body painting. The method of execution of both bark paintings is intended to produce a shimmering effect.

The desire to produce a visually vibrating surface is also evident in the canvases of Ronnie Tjampitjinpa and Two Bob Tjungurrayi, which resonate through the use of concentric shapes. By way of contrast Jimmy Pike's Jilji — sandhills, 1983, reverberates purely through the use of high-key colour. The strong verticals evoke the shimmering heat of the Great Sandy Desert.

Some artists favour overall visual textures to evoke the land, as in the scumbled surface of Maxie Tjampitjinpa's Bush fire, 1991, and Emily Kame Kngwarreye's Seeds of abundance, 1990, where the image is reduced to one of dots to produce a luscious surface. The process Judy Watson uses in her paintings, of which Heartland, 1991, is typical, involves spreading washes of paint and pigment onto flat unstretched canvas to produce gradations of density and colour which echo the contours of the natural landscape as seen from above. In this work Watson overlays this surface with a veil of spirals, save for one area which becomes the heart of the painting.

Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri achieves similar effects by applying dots of paint to the canvas while the background colour is still wet. Men's camps at Lyrrpurrung Ngturra, 1979, evokes the contours of the desert landscape. The surface of this painting forms the pictorial context in which conventional symbols and images interact. Similarly, Patricia Lee Napangarti's The death of the Tjampitjin fighting man at Tjunta, 1989, describes the encounter between a famous fighter and a group of men which leads to the former's demise. The concentric circles and U-shapes, representing people and places and painted in bold solid colours, stand out against a ground of spattered and dripped paint. Jack Jampijinpa Gallagher and Carol Napangardi, in Fire Dreaming, 1986, achieve the same effect by strewing dots confetti-like over the surface.

Ada Bird Petyarre's Sacred grasses, 1989, disorientates the viewer by projecting two simultaneous perspectives. The ground of Ada Bird's painting is black, against which dots of various sizes and colours appear seemingly at random. Naturalistic plant forms line the perimeter of the canvas directing the eye inwards. The dots can be read as stars, and the viewer seems to be looking up through the grasses to the sky. The pattern of dots at the centre of the painting forms two adjacent rectangles similar to the shapes of women's ceremonial grounds. Now the viewer is looking down to the ground.

Sensation in the paintings of Michael Jagamara Nelson and Mick Gill Tjakamarra is derived through the use of bright colours. The colours and the density of the paint give the works a rich sheen similar to that achieved in ceremonial body painting. Colour is equally important in bark painting. Les Midikuria mixes natural pigments to get a range of pinks, greens and other hues in Gichanja, white apple tree, 1989, where the distinction between foreground and background is blurred by the density of the images. Similarly, the surface of Don Gundinga's Honey Dreaming at Walkumbimirri, 1984, is animated with a profusion of animal and human figures, plants and ritual objects. The work seems to lack the central focus common to much central Arnhem Land painting and makes the eye continually swirl over the bark.

In contrast, Rover Thomas from the east Kimberley and Robin Nilco from Port Keats create tensions in their paintings along the lines formed by adjacent broad areas of colour. Nilco's painting is a contemporary interpretation of a traditional Dreaming, while Thomas evokes the swirling winds of the cyclone which destroyed Darwin in 1974.

Techniques of rock painting have been one major source of inspiration for both urban and rural based Aboriginal artists. The hand stencil features in Lawrence Leslie's textile design Yarraboalla karuldai (rock painting), 1983, for Linda Jackson, while Richard Bell uses of a variety of techniques and stencils to pose the rhetorical question Crisis; what to do about this half-caste thing, 1991, a powerful work which combines tough painting with tough social comment.

Lin Onus's Jimmy's billabong, 1988, is a teasing play on cultural and visual perspectives of the land. It depicts the same scene in two ways, simultaneously: the European view of the Arnhem Land waterhole is superimposed by the crosshatched design of the clan to whom the waterhole belongs. Turkey Tolson Tjupurrula and Johnny Warrangula Tjupurrula are famous for their expansive desert style paintings, but the two canvases presented here are an experiment in rendering the landscape in the European perspectival manner.

When the landscape is painted onto something other than the flat surface it has the power to surprise. It is not unusual in Aboriginal art for conventionally rendered images of the land to appear on ceremonial objects such as boomerangs, spear-throwers and carrying dishes. Mavis Holmes Petyarre and Rhonda Holmes Pwerle from Utopia, north-east of Alice Springs, have applied their panoramas onto the panels of old cars, Torres Strait artist Ken Thaiday's Darnley Island, 1991, an articulated ceremonial hand-held dance machine, moves in three stages to show the sun setting and the evening star rising over the painted island.

Prominent among Thaiday’s ingenious masks and machines are images of the shark and the frigate-bird, The pictorial treatment of the animal figure is another focus of this exhibition. In the bark painting Garrtjambal (Ramingining kangaroo story), 1990, Charlie Djurritjini uses a dotting technique usually associated with desert painting; while the body of the crocodile in Djawida's bark is painted with his distinctively original rarrk (cross-hatching) designs, in keeping with the practice of painters in western Arnhem Land to modify traditional clan rarrk designs to enhance visual sensation.

Fiona Foley's Eliza's rat trap, 1991, is a poignant statement on the destruction of her ancestral home, Fraser Island. This work suggests the more sinister side of animal imagery. The construction is made of a line of candles on the floor in mock worship of the seven Queensland rat traps on the wall above them. Each rat trap is painted with the Aboriginal flag; one is adorned by an image of Eliza Fraser.

Susan Wanji Wanji's gouache Emu dance, 1991, makes the link between people and ancestors in animal form through the depiction of a ceremony where participants take on the attributes of their ancestors.The human form does not always depict human beings. Among the most famous of Aboriginal figurative images are those of the Wandjina of north-western Australia, ancestors who brought the monsoonal winds, created and fertilized the earth and who left their images as paintings on the rock and cave walls of the region. Alex Mingelmanganu's painting evokes the power and scale of these images.

Equally well known are the mimi of western Arnhem Land. Mimi are regarded by the Kunwinjiku people as mischievous spirits who taught people many of the arts of living, including the techniques of painting. Their images on the walls and caves of the rocky Arnhem Land escarpment indicate that mimi have been given human form for thousands of years. Nonetheless, Crusoe Kuningbal is regarded as the first artist to sculpt mimi figures for ceremony and for sale. One of the archetypal painted images of Aboriginal Australia is that of the hunter, and mimi are often depicted in hunting scenes in rock art and bark paintings. Milton Budge re-interprets the image in acrylic paint on canvas in Hunter and roo, 1989.

Robert Campbell Jnr, like Budge, hails from Kempsey. Campbell often uses the narrative device of dividing his canvases into sections to relate an episode in two or more scenes. This technique lends itself to his personal form of social realism, where he relates and interprets the political and social history of Aboriginal people. Aboriginal embassy, 1986, relates the events of 1972 when Aboriginal people had to set up a tent embassy outside Parliament House in Canberra in order to have their voices heard on issues of social justice.

The sequential depiction of a narrative like a comic strip is common to a number of pictorial traditions in Aboriginal Australia. It is a feature of the paintings of Willie Gudipi from Ngukurr in south-east Arnhem Land, and of the Rembarrnga further to the west. Paddy Fordham Wainburranga's subject is not a religious story, but a historical one relating the Rembarrnga perspective of the beginnings of Australia's war with Japan in the 1940s, complete with aeroplanes bombing the north coast of Australia.

Scenes from daily life abound in Aboriginal art. Ian W. Abdulla's Sowing seeds at nite, 1990, continues the artist's preoccupation with recording his personal history as an Aboriginal person growing up in rural South Australia. His paintings combine images with diary-like text. Camp scene, 1990, is an extraordinary collaboration, in a region where artists often collaborate on a work, between Ruby Kngwarreye and nine other painters from Utopia, depicting images of daily life in the camp the artists share.

The treatment of the human form in Aboriginal Australia is as varied as the visions of the artists who paint it. The sheer anguish of the threatened female figure in Karen Casey's Feral cat, 1990, contrasts with the self-assured majesty of the ancestor Malawarrawurr in all his ritual finery in Jack Wunuwun's bark painting of 1990. In George Mung Mung's Minjuwidji, 1989, the lines that form the figure of the ancestor double up as contours of the land. Rick Roser, on the other hand, uses the lines made by nature in his painted driftwood sculpture of the ancestor Jundal carrying her flash of lightning.

Portraiture as such in classical Aboriginal painting varies from that tradition in European painting; it reflects the known attributes of the subject rather than the physical likeness. This attitude is evident in Bronwyn Bancroft's depiction of her brother as a warrior, in Trevor Nickolls's introverted Inside looking out, 1987, and perhaps even in the painting of the bird/ancestor in Ginger Riley's Ngak Ngak, sea eagle, 1988. The bird often appears in Riley's paintings as a witness to the events that unfold on the canvas.

Aboriginal artists acknowledge the strength of tradition while testing the elasticity of its conventions through individual interpretation. Many artists in this exhibition push painterly styles to the edge of meaning and almost beyond it, such is their delight in the process of art-making itself. In all art, narrative and meaning are inseparable from aesthetics and the gesture. Flash Pictures by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Artists focuses on the act of painting. Against the variety of backgrounds and traditions of art which inform the work of these artists, the ultimate aim is make something special — to make it flash!