Highlights and Soft Shadows

Pictorialism in Australian Photography

8 Jun – 29 Sep 1985

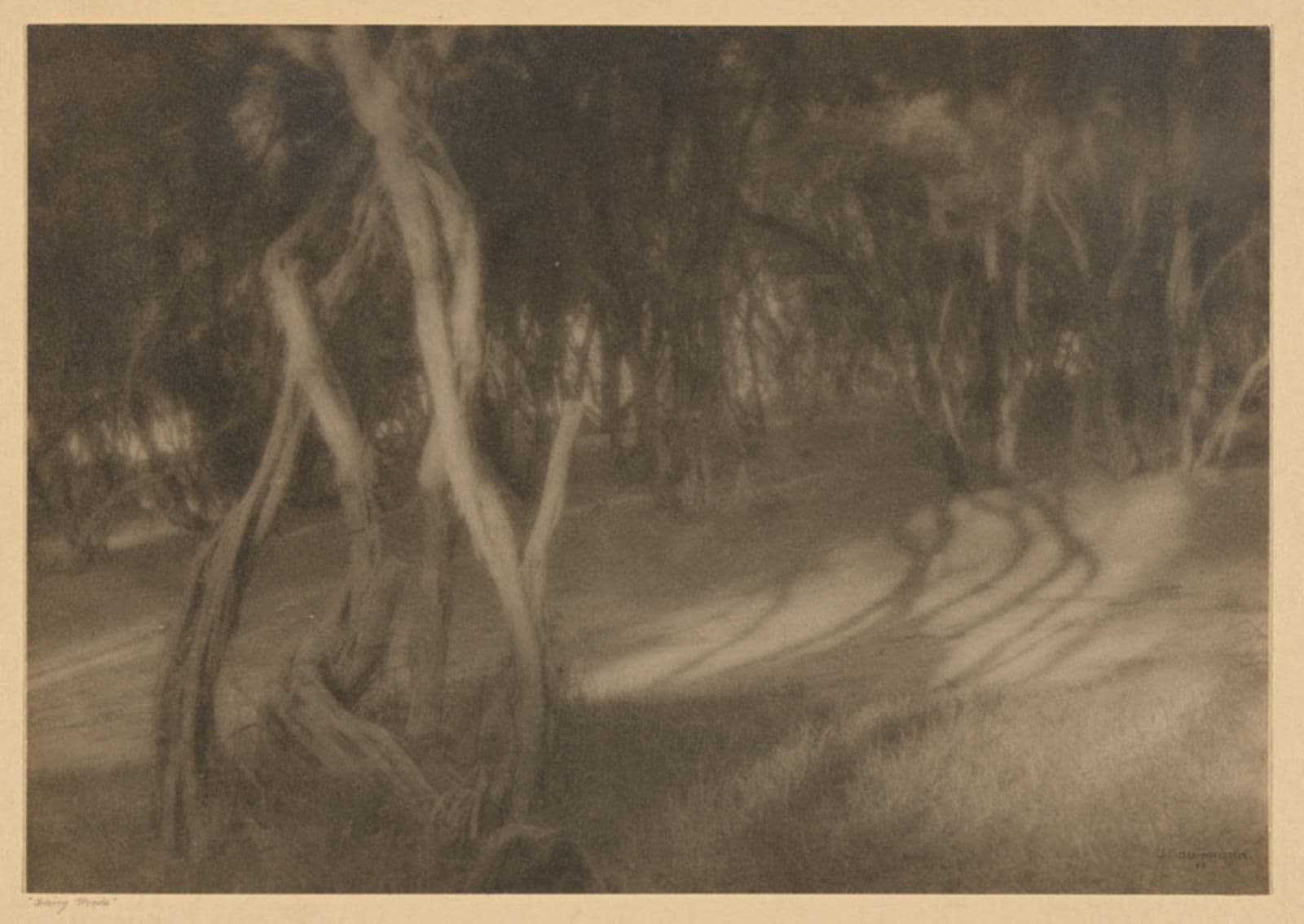

John Kauffmann, Fairy woods, c. 1920, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, Purchased 1980.

Exhibition Pamphlet Essay

The aim of those Australian photographers who worked in the Pictorialist style between the 1900s and the 1930s may best be described as 'picture making, rather than picture taking'. Australian Pictorialists saw themselves as artists working in the medium of photography and strove to have their work accepted as a legitimate art medium alongside prints, drawings and watercolours. In their quest for recognition, the Pictorialists made self-consciously artistic photographs that paralleled the popular art tastes of the day.

Towards the beginning of the century, Pictorialism was characterized by impressionistic and symbolist imagery, such as that found in John Kauffmann's Fairy woods, c. 1919. Kauffmann's Art-Nouveau inspired design and misty, romantic atmosphere repressed all local detail in favour of an idealized portrayal of nature. However, by the 1930s Pictorialism had come to be known for its 'typically Australian' images, such as Harold Cazneaux's The Spirit of Endurance, c. 1936, in which bold, dynamic composition and high-keyed, clearly separated tones evoked a vision of a specifically Australian bush landscape.

Pictorialism had its roots in the amateur camera club movement of the 1890s. Amateur photography gained considerable momentum during this period in response to the increased leisure time available to middle-class Australians and to the introduction of hand-held cameras, which were cheap and easy to operate.

Australian amateurs were introduced to Pictorialism through the work of overseas, particularly British, photographers. Since the early 1890s, soft-focus English Pictorialist images had been scandalizing the members of the photographic establishment, for whom a work's value lay essentially in its clarity and precision. By the end of the decade, Australian amateurs were also beginning to discuss this new 'impressionistic photography', or the 'fuzzy wuzzy school' as it was derisively known.

The first amateur club to produce fully-fledged Pictorialist photographs was the South Australian Photographic Society. The Society’s progressive outlook stemmed partially from the efforts of one of its members, John Kauffmann, who spent ten years in Europe where he came into direct contact with Pictorialist photography. He returned to Adelaide in 1897 and soon began to make consummate images in the new style, an example being A chestnut grove in autumn, c. 1898.

F.A. Joyner, another early Pictorialist, was also a very active member of the South Australian Photographic Society. Some of his work is distinguished by its heavy theatricality, for example The Awakening of Summer, c. 1900s, in which the photographer’s model was required to dress and pose in the manner of a Pre-Raphaelite painting. Pictorialists generally restricted themselves to subject matter that was already popular in other art mediums – ethereal women, wayward children, rural scenes, romantic back-streets and so on.

As word of their activities spread across the country and their ranks swelled, Australian Pictorialists consolidated and refined their special photographic techniques. They vehemently rejected nineteenth century photographic equipment in favour of the new hand-held cameras which produced smaller negatives and less sharp images. For printing they favoured the softer tones and matt surfaces of the new bromide papers over glossy, contrasty albumen papers. At the same time they began to experiment with entirely new techniques, such as the oil print (see glossary), which allowed direct artistic intervention in the photographic process. Harold Cazneaux’s Misty morning, North Sydney, c. 1908 is a very early example of this extensively hand-worked, extremely impressionistic style of printing. Thus Pictorialism, though conceptually based in late nineteenth century art, declared itself the new photographic style for the twentieth century.

At the turn of the century, access to overseas Pictorialism was very limited. Australian Pictorialists were unlikely to see photographs from Europe and America except as reproductions in publications such as the English Photograms of the Year. There were no exceptions however, as early as 1903, the work of two famous overseas Pictorialists – David Blount and Edward Steichen – was shown at the International Exhibition of the Photographic Society of New South Wales. Blount belonged to the British photographic group The Linked Ring and Steichen was a member of America’s Photo-Secession. Both groups were elite and prestigious fraternities of ‘photographic aritsts’. Australian Pictorialists were also greatly influenced by the vogue for etching (in particular by the etchings of James McNeill Whistler) and by the generally muted, monochromatic appearance of art reproductions in magazines and books.

By 1910 Pictorialism had gained general acceptance within the Australian photographic community and even enjoyed a measure of somewhat begrudging acceptance from the art world at large. In their efforts to bring their works to the attention of a wide public, the Pictorialists frequently exhibited in local, national and international salons. Prominent figures from the art world were often invited to judge the works displayed, medals were awarded, and a few photographs were even sold to the public. However, despite its popularity, Pictorialism’s heavily impressionistic, highly idealized style was by this time beginning to look distinctly old-fashioned – even to the generally conservative Pictorialists themselves.

Since the 1890s Australian culture had become increasingly nationalistic, with such popular figures as Henry Lawson and Tom Roberts propounding the need for a national character in Australian art. It was inevitable that these concerns would eventually affect Pictorialism. Many Pictorialists, most notably the Sydney photographer Harold Cazneaux, responded to the new Nationalism by advocating a ‘Sunshine School’ of Australian Pictorialism. It was hoped that his new ‘school’ would reflect typical Australian conditions rather than the misty, idealized and essentially European landscapes that had so inspired photographers at the turn of the century.

In 1916 Cazneaux formed the Sydney Camera Circle, which he modelled on The Linked Ring and the Photo-Secession. Whilst it never developed into the envisaged ‘Sunshine School’, the Circle did count amongst its members most of Australia’s ‘progressive’ Pictorialists, including Norman C. Deck, Cecil Bostock, Henri Mallard and George J. Morris.

These photographers all shared an awareness of contemporary trends in Australian art, such as the flattened, open forms favoured by the painters Hans Heysen and Elioth Gruner. Whilst continuing to use warm papers and reduced tonal ranges, throughout the 1920s and 1930s they made photographs with stronger compositions and in higher keys. An example of his new Pictorialism is J.B. Eaton’s The fence, c. 1938.

The growing popularity of the ‘modernist look’ in fashion and advertising illustration, characterized by bold, flat, dynamic forms, also contributed to Pictorialism’s new style. Works influenced by modernist principles include John Kauffmann’s Telegraph poles, c. 1920s and George J. Morris’s A misty day, New York, c. 1921.

Despite these concessions to modernity, however, there was never a single or coherent change of style in Australian Pictorialism. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s Pictorialists continued to make photographs in a variety of styles: from highly impressionistic landscapes reminiscent of nineteenth century Europe, to bold compositions made in Australia’s modern cities. Moreover, many Pictorialists stuck doggedly to their own individualistic styles, an example being Dr Julian Smith, who clung resolutely to his theatrical style of portraiture.

The thirty years during which Pictorialism dominated photography in Australia may be seen then to constitute a developing vocabulary rather than a dynamic progression. By the mid 1930s this vocabulary had developed to a sufficient extent to permit experimentation with entirely new photographic styles.

Martyn Jolly

Department of Photography