Lightworks

Works of Art Using Light as a Medium

4 Dec 1985 – 23 Feb 1986

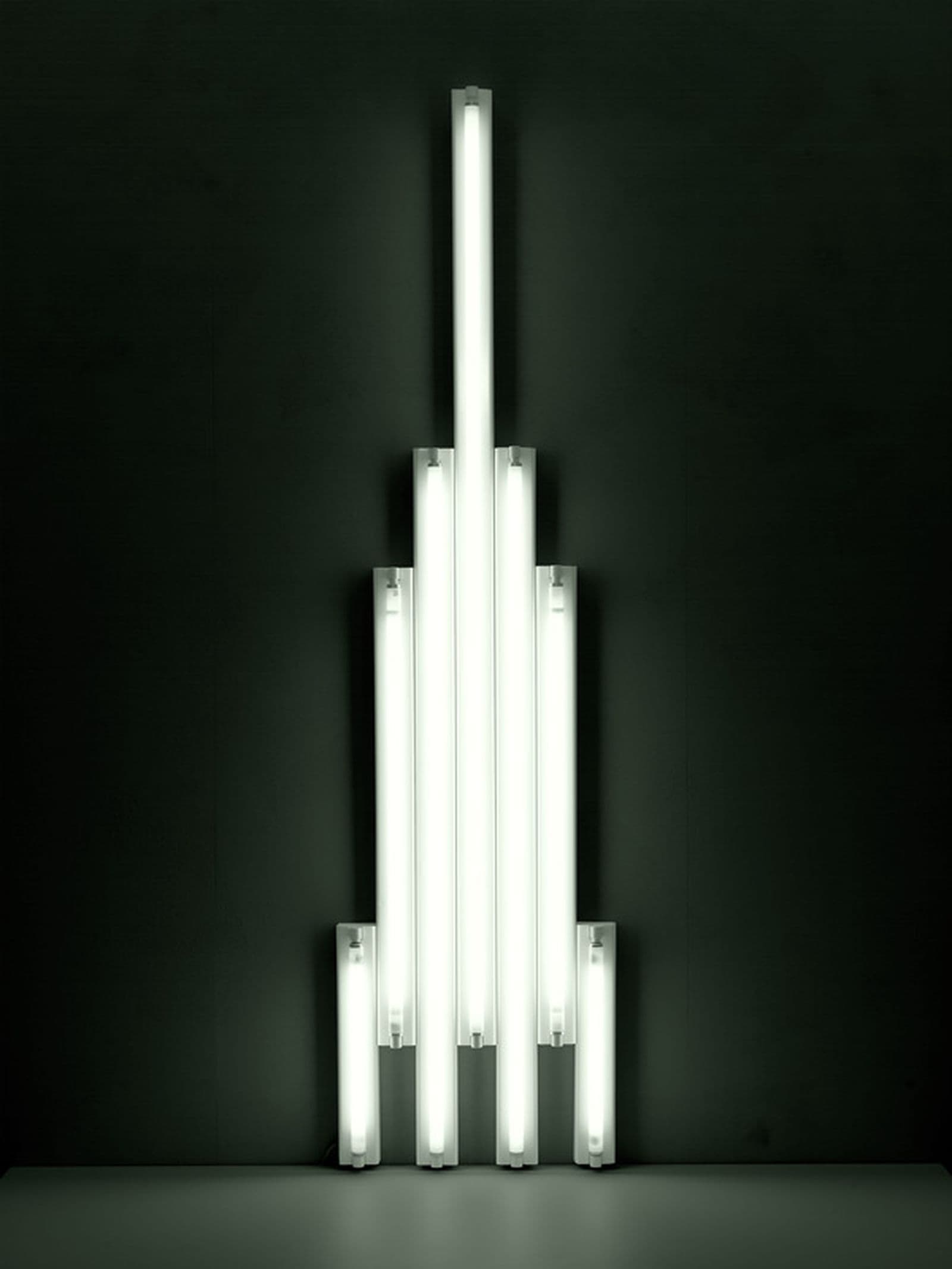

Dan Flavin, monument to V. Tatlin, 1966-69, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, Purchased 1978. © Stephen Flavin. ARS/Copyright Agency.

exhibition pamphlet Essay

Light produced artificially has been a source of fascination for artists since the late nineteenth century. Artificial light was first used to advantage in the theatre, and many artists endeavoured to capture the lurid colours and dramatic effects of theatre lighting in their paintings. The introduction of electric street-lighting and neon signs in cities in the early 1900s heralded a hectic new era, and contemporary artists painted man-made lights as the most potent symbol of the industrial age.

Nevertheless, few artists went so far as to use light itself as a medium, and the works of those who did remained but isolated experiments. It was not until the 1960s that there emerged a group of artists who used light as their preferred medium of expression.

The decade that commenced with the launching of the first sputnik saw a renewed interest in technology, and with it the realization that a technological culture was inevitable. Discotheques served up electrically amplified music in an atmosphere of flashing and coloured lights, projected slide images, smoke and mirrors, demonstrating the potential of artificial light on the senses. These factors, and ready access to suitable materials at low cost, created a climate for effective experimentation in the field of light media.

The two works by Robert Rauschenberg in this exhibition are drawn from Publicon-Stations, 1978, a series of six box sculptures, constructed out of assorted materials from the artist's Florida studio. No item was considered too ordinary, nor too unusual, to be accommodated in this three-dimensional assemblage of interlocking objects. The light leaking from the doors of the Publicon-Stations acts as an invitation to discover the contents of these austere receptacles. Inside the boxes, an extravagant combination of coloured and reflective surfaces is illuminated by lights which are simple domestic fixtures.

In The Opti-can royale, 1977, Edward Kienholz has transformed a discarded kerosene tin into a television set. By inference, the news provided to the consumer society through this appliance is equally disposable. As a prestige light source, television is ubiquitous and is found wherever electrical power is available.

Dan Flavin also makes use of 'found' elements in his geometric arrangements of store-bought, ready-made fluorescent light fixtures. Flavin's ‘Monument’ for V. Tatlin, 1966-69, was made as a tribute to the Russian artist Vladimir Tatlin (1885–1953), who insistently attempted to achieve a fusion between Art and Engineering. Flavin uses pure white light in this work to emphasize the dynamic structural design. By contrast, the regular lattice of Untitled (for Robert with fond regards), 1977, holds a showy array of coloured tubes and relies on the capacity of light to expand and define the space which the structure divides.

Neon tubing, perhaps the most easily shaped of light sources, can be used as line by the artist. Keith Sonnier uses neon line in space much as a painter would manipulate lines on a canvas, and in Untitled, 1969, he balances coloured linear elements against circular glass shapes. The transparent glass mirrors the environment and acts as a conductor to the light. Sonnier's Expanded sel diptych, 1979, continues this preoccupation with coloured line. Exploring the free-form possibilities of neon tubing, Sonnier uses the black lines of the electrical leads in his composition.

Unlike Sonnier's abstractions, which are far removed from the flashy vulgarity of advertising culture normally associated with neon light, the works of Bruce Nauman and Joseph Kosuth consciously emulate the banality of the advertising sign. The title of Nauman's work, Window or wall sign, 1967, testifies to this allegiance, and the message it carries in fact advertises the artist. In the case of Kosuth's One and eight — a description, 1965, the work advertises itself.

While Tatlin and the artists of the Bauhaus attempted to discover what art could do for technology, the generation of artists represented in this exhibition seems to have asked what technology could do for art. Mario Merz, however, questions the legitimacy of technology itself, and brings together man-made light with natural materials to emphasize the gulf separating the worlds his objects represent.

Although Merz's view of the future may be fraught with uncertainties, the continued use of artificial light as an artist's medium seems assured, and developments in the use of lasers and holography hold further promise in this field.

This exhibition is in no way intended as a definitive survey of artists using light as a medium. It is hoped, however, that this informal selection of works will go some way towards documenting the gradual acceptance of the notion that, as Dan Flavin put it, 'Electric light is just another instrument'.