Materials of Art

Painting

17 Nov 1984 – 12 May 1985

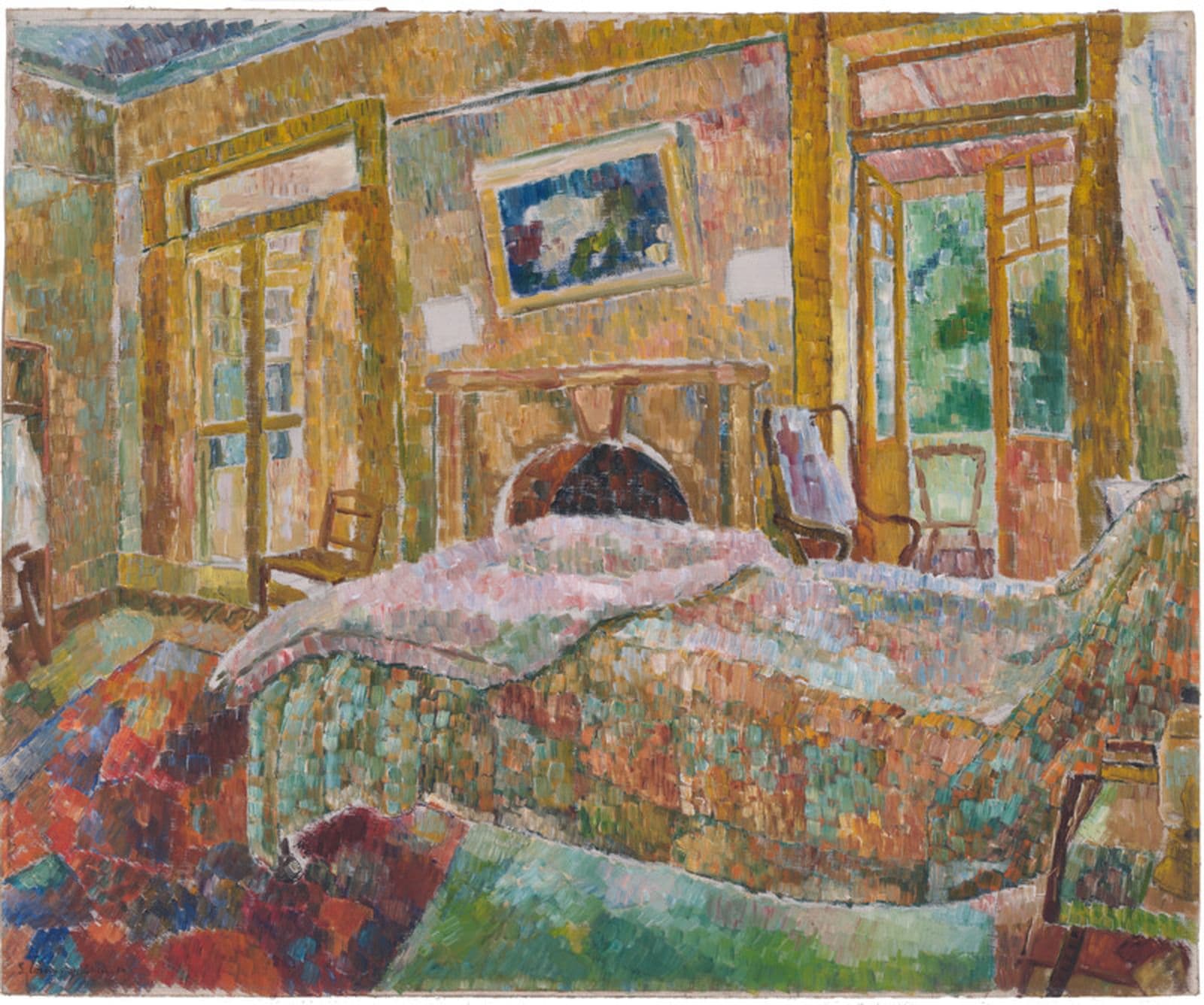

Grace Cossington Smith, Interior with verandah doors, 1954, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, Bequest of Lucy Swanton 1982.

About

The act of painting is a constant interplay between inspiration and materials: each informs the other. The unique quality of any painting is therefore influenced by the type of paint, the surface to which it is applied — the support — and the brushes or other means used by the artist to apply the paint.

Works in the Australian National Gallery demonstrate some of the possibilities exploited by artists working with various materials at different times. Watercolour, gouache, pastel, oil, synthetic polymer paint and Aboriginal bark paintings are all widely represented.

Watercolour, one of the oldest media, may be transparent or opaque. An opaque form of watercolour sometimes called body colour was used by the Egyptians and medieval manuscript illuminators. It became particularly popular among French water-colourists of the eighteenth century and 'gouache', usually pronounced 'gooah'sh', has been the accepted name of opaque watercolour from that time. This medium is marketed as poster paint and designer's colours today.

The popularity of transparent watercolour which allows the pale tone of the paper to show through the paint to create highlights developed between the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Watercolour dries quickly and in materials and equipment is light, compact and portable, making it ideal for outdoor sketching. It has been widely used for botanical, zoological, geographical and architectural illustration, and was a popular medium in the hands of artists attached to eighteenth and nineteenth-century expeditions of discovery. This medium is sometimes referred to by its French name 'aquarelle'.

Pastels, which are dry colours formed into sticks, are used for drawing; works in pastel are catalogued as pastel paintings when the colour forms masses rather than lines. Outline drawings in coloured earth, charcoal or chalk on rock dating from prehistoric times may be regarded as the earliest pastel drawings, but pastel painting has been known only for about two centuries.

Oil painting seems to have developed during the fourteenth century, possibly slightly earlier, in Germany, Italy, France and England. Long before the development of the elaborate oil techniques of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, oils were used in combination with other media. Oil glazing, for example, was used in tempera painting from early times and oil and varnish glazes were applied to tin and silver to make them resemble gold. From the fifteenth century onwards painting in oils became a flourishing art.

Synthetic polymer paint is the term used in art museums to designate a wide range of recently developed paints of similar characteristics. Acrylics and polyvinyl acetate are the main types; brand names are Ripolin, Hyplar, Liquitex, Politec, Aqua-tec, Shiva and Cryla. In recent years Australian Aboriginal artists have turned to synthetic polymer paints to give permanent expression to images traditionally expressed in more ephemeral forms.

The content on this page has been sourced from: French, Alison. Materials of Art : Painting, Gallery 8, 24 November 1984 to 12 May 1985. Canberra: Australian National Gallery, 1984.

Paint

The essential components of paint are colouring matter or pigment, and a binding medium. Fine particles of pigment are suspended in a fluid medium which binds them to the surface of the support when the paint dries.

Pigment

Pigment is the colour itself. It may be extracted from a vegetable or mineral source or produced synthetically. Natural sources are inorganic earths, prepared by grinding and sifting clays with a high metallic content; ores reduced to pigment by crushing; and organic carbon compounds. Organic pigments tend to be less stable and more likely to fade than inorganic pigments.

Colour is the most important property of a pigment, and hue, purity and brightness depend upon the colour absorption, size, shape and texture of the pigment grains. Paint must be capable of being applied evenly and smoothly and this requires a uniform grain size.

In older paintings, pigments are generally rather coarse. Granular, crystalline pigments give a certain pleasing quality to paint films that cannot be achieved with the fine, uniform particle size which is the result of modern mechanical grinding.

Pigments produced from mineral ores consist of crystal fragments whose shape depends on the cleavage properties of the crystals; azurite and cinnabar vermilion are examples. Many raw earth pigments consist of small, separate particles of irregular size and shape. In the manufacturing process the earth is stirred in large tanks of water and let stand to allow coarser particles to settle while finer particles are held in suspension. The liquid is drawn off from tank to tank, leaving a successively finer deposit in each. Green earth and raw sienna, for example, are produced in this way.

Pigments formed by the corrosive action of chemicals upon metals are usually coarsely crystalline, like white lead and verdigris, while products of fumes or smoke, such as zinc oxide and lamp black, are of fine, uniform particle size. Prussian blue and indigo are extremely fine grained, but emerald green, verdigris and cobalt blue are comparatively coarse.

Artificial production of pigments began early in the eighteenth century. Prussian blue was discovered in Germany about 1704; cobalt green about 1780, zinc oxide in 1782 and cobalt blue in 1802. Chromium, discovered in 1797, derives its name from the Greek word for colour, and from it more pigments and a greater colour range have been obtained than from any other element.

Pigments can be derived unusual sources. Indian yellow (purree) was originally prepared in Bengal from the urine of cows that were fed on mango leaves. Its manufacture is now prohibited by law and the Indian yellow used by Grace Coddington Smith is a synthetic substitute. Winsor lemon, cadmium orange, yellow ochre and Naples yellow are other yellows she used. In an interview with Hazel de Berg (16 August 1965) she said: ‘My chief interest, I think, has always been colour, it has to shine; light must be in it, it is no good having heavy dead colour’. Light is a major concern in her oil painting Interior with verandah door, 1954, in which yellows predominate.

The indigenous materials of the Aboriginal painter are obtained from the local environment as earth pigments. Charcoal or manganese deposits supply black; lumps of pipeclay or gypsum give white. Red and yellow ochre stones are ‘owned’ and used by particular clan groups. Pigments of superior quality are traded over long distances. Some pigments have spiritual significance because they are mined at sacred sites; for example, the white delek is obtained at a Dreaming site of the Rainbow Serpent, Ngalyot. Nuggets of delek can be obtained only during the dry season while Ngalyot sleeps.

In the painting by Balgurubu of a Maraian (sacred) Crocodile from western Arnhem Land, the usual red ochre ground colour which imparts ‘power’ to the bark is overlaid with a coarse layer of yellow. (Balgurubu, Crocodile dreaming, c.1979.

Medium

Pigment is dissolved or suspended in a suitable fluid – the medium – to enable it to be handled, manipulated by the artist, and adhere to the surface of the support. The effect a pigment produces will depend on the medium in which it is held. Most pigments can be used in all types of paint, and the characteristics of a particular paint depend on the medium. Oil, watercolour, gouache and synthetic polymer paint are fluid and wet while pastel is dry; oil is slow drying while watercolour, gouache and synthetic polymer paint are quick driving; oil and synthetic polymer paint have more body than watercolour and gouache.

Paint must usually be diluted in order to allow colour to be applied in various strengths according to need. Oil paints are usually diluted with turpentine; watercolour with water.

The medium also determines the suitability of the support. The denser oil and synthetic polymer paints, for example, usually require a firmer support than paper, so they tend to be applied to canvas or wood.

The essential ingredient of the medium in oil paint is a 'drying' oil, which has the property of forming a firm elastic surface when exposed to air in a thin layer. Drying oils most commonly used in oil painting are linseed, walnut and poppy oil; the 'drying' or setting of a linseed oil, for example, involves two chemical changes. When exposed to air it oxidizes (absorbs oxygen) and when oxidization is complete the product is polymerized. When oil paint is applied thinly, a painting such as Brett Whiteley's Christie and Kathleen Maloney, 1964-65, can take several months to dry while the slabs of oil paint on Leon Kossoff's Dalston Junction with Ridley Road street market Friday evening, November 1972 would have dried over several years.

'Polymer' means 'many parts' and a polymer molecule is composed of many smaller molecules joined together until there are hundreds or thousands of atoms in the polymer molecule. Drying oils become polymers after they have dried, whereas the medium in synthetic polymer paint is a polymer before it is applied. Polyvinyl acrylic and styrene resins are synthetic resins produced by polymerization.

Synthetic polymer paints were first produced for industrial purposes; they did not become commercially available to artists until the mid-1950s in the United States and the mid-1960s in Great Britain. The common medium is a synthetic resin which will mix with water or another solvent, such as white spirits, to form an emulsion. (In an emulsion, drops of one liquid are suspended in another; a well-known example is salad dressing made from oil and vinegar.)

Both synthetic polymer paint and oil paint allow great flexibility of manipulation and produce a wide range of textures but each has a unique character. Mixing drying oils with finely powdered pigments can give them a richness and brightness which differs from the sheen of a synthetic resin. Synthetic polymer paint dries rapidly but the slow drying time of oil paint allows the artist more opportunity to make changes while painting. Tom Roberts's Portrait study of a young woman, c. 1898, reveals the way an artist builds up a painting in several layers of paint. Burnt sienna oil paint, diluted with spirits of turpentine, has been brushed direct onto the tinted priming to block in forms. This semi-translucent underpainting is selectively exposed to create the impression of shadows at the neck and beside the mouth and contrasts with the adjacent layers of denser overpaint. Tom Roberts's more finished work, An Eastern Princess, 1893/c 1898. has many more layers of paint.

Many artists are attracted to synthetic polymer paint because it combines flexibility of handling, expressive quality and durability with quick drying. It is well suited to creating heavily textured surfaces; squeezed direct from the tube or applied in thick or thin brushstrokes it adheres to the support immediately and can be dry within a few hours. Dick Watkins has used all these ways of applying synthetic polymer paint in A prodigy in search of himself, 1980. The colours are applied so freely and quickly it could almost be said that Watkins was drawing with paint. Synthetic paints can also produce clear fields of colour – flat, even surfaces with considerable body and a semi-matte finish – or they can be thinned to transparent glazes.

In watercolour and gouache the common medium is a gum. It is usually gum arabic, produced by several species of Acacia in Africa, India and Australia. Gums swell or dissolve in water to form clear viscous solutions or mucilages. Transparent watercolour paint is finely ground pigment suspended in gum arabic dissolved in water; gouache is watercolour to which white pigment (body) has been added, giving it a characteristic opacity and texture. In use the water evaporates and the gum arabic binds the pigment particles to the surface of the support. Other water-soluable binders which can be used with both forms of watercolour are glue, egg white, egg yolk, and casein.

Watercolour and gouache are sold in small dry cakes in pans, or as a moist paste in jars or tubes with screw caps. The dry colour must be taken up with a wet brush, the paste may be applied at full strength from the container; both may be diluted with water. As it dries by simple evaporation, hardened watercolour paint can be made usable by moistening it again, unlike oils and synthetic polymer paint, which must be kept sealed to ensure that they remain workable.

The simplicity and portability of watercolour make it a favoured medium for travelling artists. Augustus Earle’s portrait sketch of the Prime Minister to Bey of Tripoli, 1816, was made when Earle’s ship made a stop on the north coast of Africa. Later, on one of his many sea voyages, Earle was stranded on the island of Tristan de Cunha for eight months before a passing ship took him to Hobart and he went to Sydney soon after. During a stay of about two years in New South Wales and New Zealand he made many watercolour landscapes and portraits, and some in oils, and became one of the first suppliers of artists’ materials in the colony.

Although transparent watercolours were used as a sketching medium much earlier, it was not until the mid-eighteenth century that they came to be recognized as comparable to oil paints. Russell Flint’s Odysseus in Hades, 1914, is a finished watercolour executed in a studio. The transparency and short drying time of watercolour suits it to the overlaying of different washes to create rich colour effects. These are somewhat similar to oil glazes but have a unique lightness and delicacy.

Gouache, the opaque form of watercolour, is particularly suitable for preparatory studies for works in oils and synthetic polymer paints because its consistency can be varied considerably. It can easily be manipulated to achieve different effects and it dries quickly. Bridget Riley used gouache in the preparatory study for her large work in synthetic polymer paint, Gamelan, 1970. Her concern with optical effects and colour relationships requires pure solid colour with no textural distractions and both gouache and synthetic polymer paint can be mixed to a smooth dense consistency which will achieve this, especially when applied with fine brushstrokes. Leon Kosoff's Dalston Junction with Ridley Road street market, Friday evening, November 1972 is painted with oil paint so thick that it appears almost like a sculptural relief. Large, stiff bristle brushes and palette knives were used to heap the paint onto the firm board. Each leaves its mark in the thick paint. Kossoff's preliminary study in gouache anticipates some of these textural effects. Fred Williams painted the same landscape subjects in both oils and gouache and regarded them as independent statements. Gouache was as important to him as oil paint.

The word pastel derives from pasta, Italian for paste. The medium used in pastels, gum tragacanth, is produced by shrubs of the genus Astralagus. It does not dissolve but absorbs water into itself; when mixed with pigment it forms a stiff paste which can be moulded into sticks and dried.

Pastels allow the artist to see the finished effect of the colour without waiting for the work to dry. The final effect of pastel is achieved immediately it is applied and this often gives the work a characteristic intimacy and immediacy. The surface usually has a dry chalky quality.

Pastels cannot be mixed before use and blending must take place on the surface. Each colour must initially be applied in individual strokes. The colours can then be rubbed into each other with a finger or a paper, felt or leather stick called a stump. Manufacturers supply pastels in comprehensive sets, sometimes of several hundred colours, but many artists use only a few basic hues. Boxes of twelve are often used for sketching.

In earlier times pigments used in many Aboriginal paintings contained no binding medium. When the paint flaked from the support the image was ceremonially retouched. As more durable paintings on bark or wood were required, pigments were mixed with beeswax or turtle egg, which Aboriginal artists still say is the proper medium for a lasting paint surface. The juice of the tree orchid (Dendrobrium sp.) was also widely used. It may be mixed with pigment or rubbed over the surface or the bark before the paint is applied. These natural binders do not saturate the pigments: their characteristic matt powdery texture is retained. This can be seen in Birrkurda by Libunja, c.1968.

Many Aboriginal painters grind lumps of ochre or charcoal on the flat surface of a large stone and mix the pigment with the binding medium and water. Traditionally, each Aboriginal painter collects materials for natural deposits and mixes them in small quantities as he works.

In many contemporary bark paintings the medium is a mixture of polyvinyl acetate glue, a synthetic binder, and water, and it dries with a dense smooth finish. A high proportion of glue in the mixture results in the glossy sheen evident in Luma Luma’s Funeral ceremony painted in 1984.

Ground

Artists paint on many different materials, most of which need to be specially prepared to receive the paint. The application of a ground will protect and modify the surface of the support. The ground traditionally applied to canvas consists of a size to fill the pores and seal the fibres, and a priming which provides a suitable working surface for the paint.

Size is used to protect the support from the oxidizing effect of the drying oils in oil paint but it also lessens its absorbency and may be used for this purpose with synthetic polymer paint. The size generally preferred is animal hide glue applied direct to the canvas.

Priming modifies the absorbency and texture of the support as well as the colour of the overlaid paint. White lead in oil with a little turpentine is the traditional high-quality priming for oil paint on canvas, but today an opaque oil-based paint, white or tinted, or a synthetic polymer primer may be used. Synthetic polymer paint may be applied to unprimed canvas, but it is usually used over a primer of the same composition. Canvas and composition board and some other supports can be purchased already sized and primed. When an artist wishes to reuse a canvas, a layer of priming will obliterate the first image and establish a new ground for the second.

Wood is often primed with thin gesso, a mixture of slaked plaster of paris, whiting or chalk, with casein or animal glue. Well prepared gesso is hard and can be finished to an ivory-like surface with good paint absorbency.

Support

The material the artist chooses to work on has a considerable influence on the final image; even where the support is completely covered with paint its texture blends or contrasts with the paint and where it is exposed it introduces colour as well.

Paper

The most used support for watercolour and pastel is paper. Thickness, weight, finish, grain, texture and colour determine the unique character of any paper and its suitability for a particular paint or technique.

Heavy papers are usually preferred for watercolour because they can take water without wrinkling. Lighter papers must be dampened and stretched on a firm backing before use. Different paper surfaces receive the paint differently and absorbency is as important as texture. Watercolour paper is usually sized in the course of manufacture; if it is not the paint will be absorbed before the colour can be worked on the surface.

An open or coarse textured paper is best suited to transparent watercolour because the irregularities catch the light. Smoother surfaces are more suitable for gouache. As gouache is opaque it may be used on darker-toned papers, for the paint lies on the surface of the support, unlike transparent watercolour where tiny particles of pigment become enmeshed in the fibre, causing an effect similar to a stain. Gouache has an appreciable thickness and its lightness is imparted by white pigments (lead or zinc oxide) added to the colour during manufacture; its opacity permits overpainting and it is possible to lay light paint over dark to build up a picture in solid colour. In Rock lily, 1953, Margaret Preston contrasted the black painted support with areas of solid colour applied through a stencil with a dry, stiff brush in short sharp strokes.

The more transparent watercolour is diluted the greater the transparency of the resulting wash and the more the surface of the support shows through. Monochrome studies in watercolour, like Lake of Bala, c.1820, by John Glover, depend on the dilution of paint with water rather than the addition of white pigment to achieve light tones. In some areas the white paper is left unpainted to contrast with adjacent washes and function as a bright highlight.

Light cream paper glows beneath a thin wash of blue paint diluted with water in the sky of Norman Lidsay’s watercolour Rendezvous with a faun, 1922, suggesting atmosphere and light. The strongly grained paper takes the paint unevenly, creating contrasting depths of tone and luminous effects. A broad wash brush with fine soft hair, (sometimes known as a ‘sky brush’) would have been used to sweep the paint on, achieving the effect of a continuous curtain of colour.

John Russell chose paper with a smooth grain for the lively sketch Bois Winter, 1912. The paper was heavily sized to give a hard finish; overlaid washes retain their brilliancy on it. On this surface, varying effects are produced when the same colour is applied in different consistencies. Crimson diluted with water and brushed lightly onto wet paper becomes semi-translucent, while concentrated crimson applied with a fine, dry brush results in a strong vibrant line. Pencil overdrawing is used to heighten the forms.

The paper used in House among the trees, 1920, also by John Russell, is relatively unsized. Russell exploited its absorbency by dampening the surface and applying the paint while the paper was still moist. Marks of drawing pins can be seen where it was attached to a drawing board for stretching while wet to avoid uneven shrinkage or expansion of the paper. Watercolour washes were brushed on 'wet in wet' so that the damp colours blend into each other and the edges blur. Soft, hazy lines were created by scraping back through the wet paint, probably with the tip of the paint brush handle, so that the paper shows through.

Handmade papers are traditionally preferred for watercolour; they can be recognized by their irregular edges. Fine papers are embossed during production with the manufacturer's mark, the watermark, which can be seen by holding the paper up to the light.

Pastel may be used on papers of varying degrees of roughness. The colour must be able to adhere to the surface, so the grain of the paper should be such that it will file off the pigment particles and retain them. Specially prepared pastel paper has a coating of fine-grained inert material such as pulverized pumice stone or silica, which acts like a fine sandpaper when pastel is drawn over it.

The textural effect of pastel is influenced both by the surface and by the pressure with which it is applied. Pastel used lightly on grained paper creates textural and tonal contrasts; this can be clearly seen in Ralph Balson's Pastel no. 19, 1951.

Coloured pastel papers are often used. Separate unblended pastel strokes allow much of the support to be seen and its colour may contribute greatly to the effect of the image. Arthur Boyd used a wide range of coloured papers for his series, The life of St Francis. Warm yellow paper glows beneath a delicate web of separate pastel strokes in The Wolf of Gubbio with St Francis's head in a tree, 1964-65. Discrete strokes overlaid in different directions create a flickering interplay of rich colours. The technique has affinities with weaving and a series of tapestries was based on these drawings.

Canvas

Painting on woven fabric goes back to Ancient Egypt. Unlike wood, canvas does not split, warp, or harbour worms, it can easily be obtained in a suitable size for most work and it is light and easily transportable. Stretched over and attached to a wooden frame (the stretcher), canvas remains taut yet flexible and responsive to the application of paint. Used with synthetic polymer paint it is flexible enough to stand up to the rolling and unrolling which is sometimes necessary when large works must be transported.

Linen, hemp, jute, flax, cotton and combinations of these in various thicknesses and weaves have been used for canvases. Each material receives paint differently and gives a unique texture to the painting. A smooth, even paint surface can be obtained on a canvas finely woven from flax, and fine cotton canvas, too, provides an even ground for bands of flat colour. In Bridget Riley's painting Gamelan, 1970, a smooth acrylic priming over the entire area further refines the surface. Synthetic polymer paint has been applied selectively over the primer, which glows beneath the orange paint or functions as a given colour. The bright white intensifies the colour values of the adjacent stripes to create extreme optical contrast, heightened by the matt opacity of the primer and the luminosity of the thinly applied translucent colour. The colours seem to pulsate: constant contrasts from warm to cool, thick to thin stripes create rhythms for the eye similar to the way different sequences of musical notes create rhythms for the ear. (A gamelan is the name of an Indonesian orchestra comprised mainly of percussive instruments.)

Bridget Riley's work with optical effects and colour relationships requires pure solid hues with no textural distractions and synthetic polymer paint can be manipulated to achieve flat, clean areas of smooth, even colour. The paint blends easily edge-to-edge along the brush strokes and evidence of separate brush strokes can be eliminated. On the other hand it may be applied with a firm, discrete edge to create precise boundaries between adjacent colours.

Synthetic polymer paint may be applied directly to unprimed canvas, which is extremely absorbent. Colour sinks into it and the density of the paint is reduced and the strength of the colour weakened to create lighter tones without the addition of white.

In Beta Nu by Morris Louis, a large expanse of medium-fine-weave cotton duck, unsized and unprimed, is left unpainted to vary the surface texture. Rivulets of greatly diluted synthetic polymer paint, which have been poured straight from the container diagonally across the canvas, are absorbed into the fibres, staining them and creating soft translucent edges. In this painting, variation in the density of the paint is not achieved by modifying its consistency before it is applied but by the way in which it is absorbed by the unprimed canvas. Louis worked with a paint manufacturer to develop a paint formula of an appropriate consistency.

Beta Nu comes from a series of over 120 paintings called Unfurleds, which were identified after Louis’s death by letters from the Greek alphabet. In each work the irregular rivulets of colour unfurl diagonally downwards and inwards either side of a blank centre. Conventional painters usually focus their colours and shapes in the centre, Louis’s interest is in voids and connections. Beta Nu is one of the largest Unfurleds.

Wood

Wood is one of the earliest materials used as a support for painting. Although the width of single boards is limited, the ease with which they may be joined and glued allows the construction of large flat surfaces. Easel painting on wood existed in the IV Dynasty in Egypt and in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries wood was very popular with Italian painters, who used poplar and other timbers. Northern painters preferred oak, although in the Netherlands and England several other timbers were also used.

In Australia in the late 1880s Arthur Streeton and his friends used fine-grained cedar cigar box lids for small-scale outdoor sketches and 'impressions'; their common size of nine inches by five inches was the origin of the name of The 9 x 5 Impression Exhibition of these works.

Cigar labels can still be seen on the reverse of Sandridge by Arthur Streeton. The masts of the boats in this painting were depicted by scraping away paint with a fine implement to reveal underlying layers and the cedar support. The wooden panel is an ideal surface for the firmly incised lines, which have a sharpness and clarity that could not be achieved on flexible canvas. Fine ridges of paint along the edges of the lines accentuate the forms of the masts.

Arthur Streeton's South Head, c. 1895, was painted on a fine-grained wooden panel originally intended as a template for a fretwork clock-holder. Both absence and presence of paint have been used to create the image; unpainted areas of the panel create textural contrast. The wood asserts itself independently of the paint but the yellow-brown tones of both blend to create the foreground of trees and hills. Streeton has masked the upper surface of the panel with the blue of the sky and his selective exposure of the wood in the lower section mimics the texture and colour of land and tree trunks.

Sometimes a cradle is fixed to the back of a wood panel to prevent it warping with changes in humidity. Narrow, slotted strips of wood glued to the back parallel to the grain allow unglued transverse strips to move freely in the slots, permitting normal expansion and contraction across the grain but holding the panel flat.

Plywood

Originally developed as a building material, plywood has also been utilized by artists. Three, and sometimes five or seven thin sheets of wood are glued together with the grain at right angles. Plywood is in some respects stronger than solid board of the same thickness and large panels are less likely to shrink and warp than solid timber of the same size, althought poorly made plywood may come apart layer by layer after a short time. Quality plywood makes a very durable support.

Trees in wind, c.1927-28, by Grace Cossington Smith is painted in oils on plywood. An unfinished street scene, Turramurra landscape, c.1926-27, is on the reverse of this work. The surface sized with transparent animal glue can still be seen. No priming intervenes between the size and the paint layer and the board has yellowed and darkened as a result of exposure to light. The sized timber adds more than colour and texture: the deliberate contrast of paint and wood throughout the image gives composition unity and strength.

On the front of this double-sided work a priming of thin gesso (a mixture of slaked plaster and animal glue) has been applied over the size, producing a light, bright white. Exposed priming contributes to the image in many places. It seems to flicker through the edge of the foliage forms, contrasting with the grey-tinted white oil paint brushed over it: the impression of trees moving in the wind is suggested by these rapid shifts in tone.

Composition board

Artificial building board has been used since the 1950s. Generally referred to in museums as composition board, it is made by the ‘Masonite’ process: wood chips are formed into sheets under heat and pressure; the material is cemented together by the natural lignins in the wood. One side has a smooth polished surface, which on the other the imprint of the wire screen on which the sheet is formed gives it a texture somewhat similar to rough canvas.

In Homage to the Square, 1956, Joseph Albers applied a paint rich in oil with palette knife and brush, overlaying colours which eventually mask the texture of the board beneath. The texture remains evident in the border of white priming on the first square and subtly accentuates the progression of colours. Homage to the Square was begun late in Albers’s career, but it stems from his years as a teacher at the Bauhaus in Germany in the 1920s. While Head of the Design Department at Yale University after 1950 he wrote various books, including Interaction of Colour, now published in eight languages. In the series Homage to the Square he found the perfect neutral form which allowed him to explore the hundreds of different combinations of colour. In this work the paint has been applied direct from the tube without mixing or dilution to modify its consistency and colour saturation. From the centre outwards, cobalt green has been painted over mars violet, applied in turn over terra rose over cadmium scarlet painted over cadmium orange. The primer consists of two coats of flat white Alkyd and two coats of semi-gloss enamel.

Howard Hodgkin's The Buckleys at Brede, 1974-76, is painted in oil paint on plywood. The painted frame which extends the image is of wood. Hodgkin has worked on wood for at least ten years. In a conversation with Patrick Caulfield reported in Art Monthly, July/August 1984, he says of it: '... wood has such character of its own. In a piece of wood you get these beautiful wave patterns and things like that which I don't use specifically, but there is already something to work with ... a white canvas is just a piece of white canvas, it hasn't any identity of its own at all.’

Other supports

Copper was not much used as a support for paint until the sixteenth century, when it became cheap and plentiful in sheet form. It was particularly popular in Holland for small, jewel-like paintings. The Spaniard Palomino, writing in 1724, says that copper panels should receive the same preparation as wood and states that the smooth surface will not give a good bond unless first rubbed with garlic. Copper gives a hard, smooth surface for oil and synthetic polymer paint. Today the surface is usually scored and cleaned to assist adhesion and several ground layers of white metal oxide are applied. Because of the flexibility of the thin metal sheets and their susceptibility to denting, paintings on copper must be framed and made rigid with a firm backing board.

Glass and perspex provide large, flat rigid supports for paint, but the smoothness of the surface encourages a tendency to blurred edges, and streaked colour is inevitable. Soft hazy effects can be easily achieved and images painted directly on these materials may be viewed through them by transmitted rather than reflected light.

Ivory in thin slices has been widely used for painting miniatures in watercolour, especially since the mid-eighteenth century when it replaced enamel in popularity, particularly in France and England. Ivory is very dense and the surface can be smoothed to a hard, even finish suitable for detailed brushwork. Fine sable to marten hair brushes are generally used and corrections are made by scraping back with a fine needle. A thin coat of transparent varnish has been used to protect the surface of Bernice Edwell’s Self portrait on ivory, c.1918.

The use of silk as a support for paint has a longer history in Asia than in Europe. For watercolour painting it must be tightly woven from extremely fine fibres to produce a relatively smooth surface. Its high absorbency creates soft colour effects which contrast with the lustrous unpainted surface; blurred edges are produced where the wash runs along the fibres by capillary action. The initial wash, diffused into the silk, creates a sized ground and a build-up of colour can be achieved by the application of further washes after the first have dried. Thea Proctor’s The Swing, c.1925, has been painted on weighted silk taffeta.

Bark painting derives its name from the support rather than the paint; Aboriginal painters also painted on rock, wood and human skin. The bark used for painting is obtained from the inner layer of stringybark peeled from the tree during the wet season. Differences in thickness, texture and pliability determine the character of each bark and influence the painting accordingly.

In earlier time bark was prepared with stone axes, spears and pieces of sharkskin; today it is cut and trimmed with saws and knives, carefully dried to minimize warping, and smoothed and cleaned on both sides. To prepare the bark for painting a layer of red ochre is rubbed or painted over it. This sacred colour imparts ‘power’ to the painting and provides an even surface for the fine brushwork.

Applying the paint

Brushes are round or flat, with tips ranging from pointed to chisel-edged and rounded. They are made in a series of skilled processes designed to produce a wide range of characteristics suited to particular paints, techniques and purposes. Those intended for dense oil and synthetic polymer paints are generally made from stiff bristles. They must be flexible and elastic, and for fine work it is essential to have a point which does not divide. Natural hair or bristle, used in the best brushes, has an end forked like a twig, and these split ends must be retained if the brush is to be suitable for painting.

As well as brushes, painting knives and spatulas with thin flexible blades of various shapes and the more robust palette knives designed for mixing and stirring are all used to apply paint, the latter especially for thick applications on a large scale. Rollers, spray guns, sponges and rags are also used. If synthetic polymer paint is to be diluted and applied on a small scale, watercolour brushes may be used. Smooth blended surfaces and fine detail may be achieved with these soft brushes.

Watercolour paint is highly fluid and brushes intended for it are generally made from fine soft hairs. The finest are red sable, actually the tail hair of the kolinsky or Siberian mink; ox and squirrel hair are also used. 'Camel' brushes are not made from camels, but from various other animals, the best being squirrel. Too soft for general use, they suit some special purposes. The broad wash brush or 'sky' brush is an example; 'camel' hair is satisfactory in this case because the ability to carry plenty of paint is more important than fine control. Other special-purpose brushes are known as dabbers, stripers, fans and mops. The points of watercolour brushes must be free to recover their natural shape when drying and in the nineteenth century special ivory or wooden racks were used to hold them.

Although pastel is applied directly to the support, it may be smoothed or blended by rubbing with a finger or a tapered stick or tightly rolled leather, felt or paper called a stump, tortillon or torchon. In a traditional pastel painting such as Old bridge, Warrandyte, 1918, by Morris Cohen a velvety finish has been created by the build-up of many layers of pastel particles. The pastel has been rubbed back in some areas to produce a smooth surface.

Bark paintings are executed with a variety of brushes. Traditionally, artists in western Arnhem Land use a wide brush of frayed bark for applying the ground colour and outlining the basic composition and complete the work with brushes of grass.

In central Arnhem Land brushes made from chewed sticks or bark strips are used for drawing and infilling. Twig brushes are used in sacred rituals when images are painted in human blood. Today European style brushes are also used.

The most distinctive brush used for bark painting is the marwat, made of long human hairs bound to a stock with string. It is used exclusively to paint the fine crosshatched design know as rarrk. The artists coats the marwat in pigment and applies its full length to the surface to draw a thin line. Artists are known for their facility with the marwat, which is used with great skill and patience.

Palettes

Paints are laid out and mixed on a palette and the range of colours from which a painter typically works is often also referred to as a palette. Palettes for mixing colours may be made in various materials and shapes.

Traditional oil palettes are often made from cherry or walnut wood and are held in the hand; they may be rectangular, oval or kidney-shaped. The kidney-shaped palette rests against the forearm, being held through the bevelled thumb hole. Colours are laid out from their tubes around the edge of the palette in a sequence peculiar to the artist, who can habitually reach for the colour required without interrupting the flow of work. Colours are mixed in the centre of the palette where the mess can be cleaned off at the end of the work.

Plastic and glass palettes are particularly suited to synthetic polymer paints because dried paint can be removed from them more easily than from wood. When synthetic polymer paint is diluted to a highly fluid state a palette with bowl-like depressions may be used to hold the colour. For large-scale work colours are mixed in big containers. Watercolour also requires a palette that will contain fluid colour; a white surface is generally preferred as it enables the effect of the colour on a light-coloured support to be more accurately foreseen.

Aboriginal painters use the flat surfaces of stones as palettes.

Easels

An easel is generally used to hold the work in a vertical or near-vertical position, whatever the medium, and in pastel work it may be sloped slightly forward to allow loose particles of pigment to fall freely away from the surface.

A lightweight sketching easel for outdoor use will generally fold down for transport and have adjustable legs to allow for uneven surfaces. Some sketching easels also support a paint box or tray which enables paint, palettes and brushes to be placed within easy reach. Fred Williams’s sketching easel is an example.

Supports too large for an easel may be placed flat on a table or floor or be tacked to the wall. Scaffolding may be assembled over or in front of the work to allow the artist to work freely on any part of it.

Protecting the painted surface

Many artists apply a coat of varnish to a painting after it has dried in order to protect the paint from humidity and dust and other pollutants. The glossy transparent surface of the varnish reflects light and intensifies the richness of oil paint. Synthetic polymer paint does not require the protection of varnish, but some artists use it to modify the surface appearance of the paint. Varnish is a resin in a volatile solvent which dries to a hard, glossy, transparent film. It may be applied with a brush or as a spray.

When high-quality paper and permanent pigments are used pastel is one of the most permanent forms of painting, but it is fragile when handled. Some protection can be provided by spraying the finished work with a fixative. Very weak solutions of non-yellowing resins in alcohol, ether, or benzine are generally used. They dry rapidly through evaporation but cause subtle changes in appearance. The fixative coats the work with a fine layer of resin which improves the adhesion of the colour to the support but usually causes some loss of the velvety texture. There is often a reduction in brilliancy and softness and a more uniform finish is imposed. If pastel is not fixed, very careful handling is necessary and the work may be framed and glazed.

For centuries paintings have been displayed in frames characteristic of the taste of the particular period or artist. Wood panels are usually framed to prevent warping; canvases on wooden stretchers do not need framing for structural reasons and many large-scale works in synthetic polymer paint are now displayed unframed. Frames may be plain or elaborately ornamental; often they form an integral part of the work.

Synthetic polymer paintings and oil paintings on canvas or wood are generally not glazed unless they have deteriorated or the surface is particularly fragile. Both media are extremely durable and their tactile quality can best be enjoyed if they are unglazed. Synthetic polymer paintings on paper are generally framed and glazed, especially if large expanses of paper are exposed. Watercolours are framed and glazed if they are to be displayed.

Works of art on paper are damaged by exposure to light and in museums they are usually mounted in standard-sized mounts and stored in special boxes called solander boxes. When required for display they are framed behind perspex in standard frames the same size as the mount. In order to extend their life they are exhibited for short periods only, usually six months in every three years, or an equivalent ratio. Unfixed pastels are usually stored mounted in standard frames.

Traditional bark paintings were not conceived and produced for permanent display. Often they were not intended to survive beyond the ceremony for which they were produced. In earlier times many Aboriginal paintings were executed without a binding medium and when the pigment flaked from the support the image was ceremonially retouched to renew its ‘power’.

Many bark paintings were copies of sacred clan designs. The bodies of initiated men were painted as they lay on the ground and bark was painted in the same way. A single bark was divided into panels to accommodate several designs and more than one painter could work on a painting, which might be viewed from any direction as there was no top or bottom.

Production of bark paintings for sale and exhibition led to changes in that images were conceived in terms of vertical display and attention was paid to the technical finish and durability of the support. Contemporary barks intended for display are required to maintain their shape and strips of wood are fastened to the upper and lower edges of the completed painting to stop them curling.

Alison French

Assistant Curator, Education