Political Motives

The Batiks of Mohammed Hadi of Solo

12 Dec 1987 – 5 Jun 1988

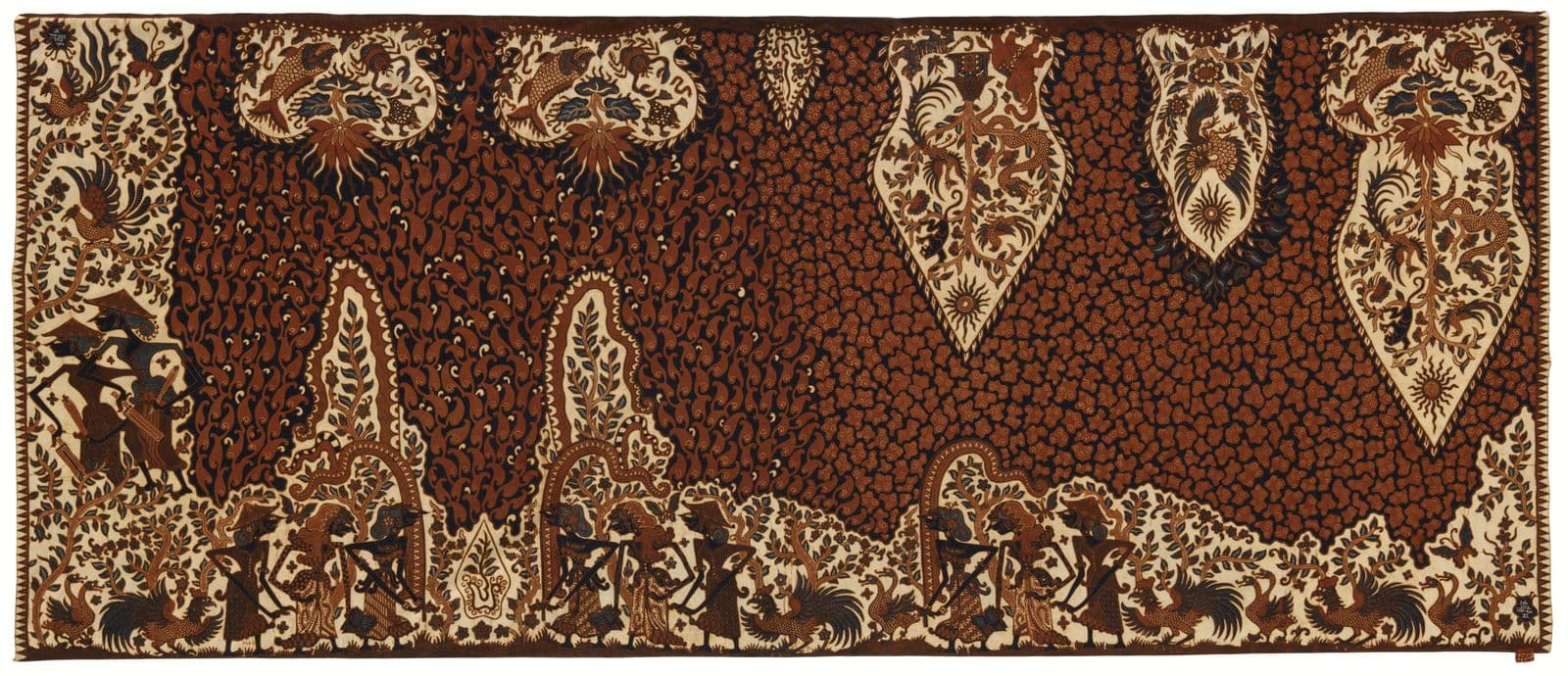

Mohamad Hadi, Srikandi as Goddess of the Indonesian Women's Movement [Srikandi Gerwani], 1964, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, Purchased with Gallery Shop Funds 1984.

About

Although traditional textiles are not usually discussed in the context of contemporary politics, the textiles of Southeast Asia have often reflected the social and political divisions of the communities that have made and used them. Traditional textiles frequently contain designs and patterns that not only symbolize power and authority but also indicate rank and status, particularly the membership of a ruling elite.

Traditional batik cloth has often reflected political changes in Javanese society, particularly changes resulting from contact with other cultures, and ancient indigenous patterns have been continually supplemented by designs derived from the exotic traditions of India, China, the Middle East and Europe. The styles, colours and design of batik cloths identify their regional origins, and distinguish in particular the clothes of the central Javanese kingdoms from those of the coastal towns. Changes in motif have often indicated new or changing political and cultural influences, and many of the historic divisions within Javanese society are represented in certain batik designs. In the traditional royal principalities of central Java a number of designs were associated with the aristocracy, and until the effective power and authority of the nobility declined in late colonial times, commoners outside the court circles were forbidden to use such designs.

The relationship between politics and batik design is clearly evident in the life and work of the Javanese painter Mohamad Hadi (1916-1983), who, for a short period during the mid-1960s, was responsible for creating some remarkable batiks with a powerful political message. Hadi used his long experience as a painter and his creative imagination to produce an innovative range of bold and dramatic batik designs that used traditional techniques and patterns as a basis for idealizing the Javanese peasant and his relationship with the land. Hadi’s ideals are reflected in the titles he gave to many of his designs: The Basic Necessities of Life (Sandang Pangan), The Golden Bridge (Jembatan Mas) and The Peasant’s Grid Pattern (Ceplok Tani). Unfortunately, few of Hadi’s batiks survived the political upheaval which occurred in Indonesia at the end of 1965.

Mohamad Hadi: in Java

Mohamad Hadi lived and worked in the city of Solo in central Java. Although he came from a devout Islamic family, he developed a keen interest in traditional Javanese culture, including the Javanese shadow puppet theatre (wayang) and the Javanese mysticism (kebatinan).

As a young man Hadi became interested in the arts and turned his attention in particular to painting. During the 1950s he became a prominent member of the Solo branch of the Institute of People’s Culture (Lembaga Kebudayaan Rakya – LEKRA), a popular left-wing artists’ association. This group of artists, writers and performers was opposed to Western cultural and artistic influences in Indonesia, and sought to establish an independent national culture based on the interests and shared experiences of the Indonesian people. Throughout the 1950s, the radical and nationalist character of LEKRA was evident in the way the organization supported the strengthening and revitalization of Indonesian folk and popular art traditions, and actively promoted a class-based, radical ideology to achieve a ‘people’s culture’.

Hadi eventually applied these ideals to the traditional Javanese textile technique of batik.1 Although it appears that he had no background as a batik-maker, some time after 1960 Hadi and his wife Sutrisni established a batik workshop in Solo as a means of supplementing their income. Although some of the batiks they produced featured floral and aquatic designs in a style characteristic of cloths from central Java and Surakarta, a number of their works used traditional forms to express a social and political awareness of the life and culture of ordinary Indonesians, in particular the peasant farmers of rural Java. However, in combining contemporary images which represented the Javanese peasantry with the forms and techniques of traditional batik, Hadi had set himself a difficult task. The production of the highest quality batik in central Java was historically associated with the conservative ‘feudal’ traditions that he and the radical nationalists opposed so vigorously. Nevertheless, these traditions proved impossible for Hadi to abandon completely, and an understanding of his work requires an intimate knowledge of Javanese culture, of which classical batik is an important element.

Thus, despite his background as a painter, Hadi made a deliberate decision to work within the established structure of classical batik, and all his designs were intended for the standard central Javanese skirt (kain panjang), which measures approximately 1 metre by 2.5 metres. The modern style of free batik painting on cloth sizes of varying dimensions —which became a popular form of decoration in the homes of the urban and Westernized Indonesian elite, particularly during the late 1960s and 1970s — had no attraction for Hadi. He preferred to use the structure of traditional Javanese batik as a means to create his own designs. His hand-drawn (tulis) designs were very carefully executed on cotton cloth of the finest quality, and he used the traditional waxing tool (canting) rather than the faster, cruder and more common block-waxing process (cap).

Hadi's batiks are greatly enhanced by his use of the rich, traditional dyes for which central Javanese batiks are famous — the blue-black indigo (tarum or nila) from the leaves of either Indigo tinctoria or Marsdenia tinctoria, and the distinctive brown (soga) from the bark of Pelthophorum ferrugineum. Hadi appears to have consciously avoided the use of the naphthol dyes that were gaining in popularity, even among central Javanese batik-makers, during this period. In fact all the Mohamad Hadi batiks in the Australian National Gallery collection were dyed in a famous workshop founded by Kanjengan Wonogiri, a well-known aristocratic woman who specialized in producing soga dyes of the highest quality. Her workshop, which was established within the precincts of the Mangkunegaran palace (one of the two royal houses of the Surakarta region), has served some of the leading batik-makers of Solo, including members of the royal family. (The classical Good fortune and prosperity pattern [sida mukti] batik in this exhibition was also dyed in that workshop; this design was traditionally worn for wedding ceremonies.)

Hadi made one important technical contribution to the batik-making process. His interest in the craft of waxing and soga dyeing led him to experiment with these traditional materials, and he and his wife are credited with the introduction of a new decorative technique, wax crackling. Hadi discovered that by modifying the pure waxes that were applied to the cream cotton cloth that formed the background of the design, he was able to produce a gentle crumpling and cracking of the wax. This cracking allowed the soga dye to seep through the wax, creating a subtle brown marbling on the light fawn background area. This crackling style, pioneered in their workshop, quickly became popular and was widely known as 'wonogiren'. The main motifs and designs appear to be superimposed over the marbled background, and this style is represented in a number of the batiks in this exhibition, in particular The Ceremonial Ear Ornament Motif on a Striped Ground (Galar Sumping Dåråwati), the Fern tendril pattern (paku) and The Giant Lobster design (Urang Barong).

However, it was Hadi's batik designs that were especially significant. He drafted his ideas into sketchbooks, and local women were employed to wax the designs on to the cloth. Although intended to decorate the traditional kain panjang skirt form, Hadi's designs reflect his experience as a painter: the patterns are conceived in a bold, clear, linear style and his batiks, unlike those of classical central-Javanese artisans, are signed, dated and often named.

Many of Hadi's designs were purely decorative, drawing upon such familiar aspects of the natural environment as flowers, plants and sea creatures. These motifs were depicted in a style typical of central Java, and were often given classical Javanese titles. A feature of many of Hadi's designs is the division of the surface pattern into two halves so that the design is subtly reversed to form the style known as pagi-soré (morning and evening), which allows the skirt to be turned around and worn on different occasions with either end of the design revealed.

- Batik is produced by applying wax to cotton cloth which is then submerged in dye; the wax resists the dye, thus creating a design on the fabric.

Classical and Contemporary: Mohamad Hadi's Batiks and Traditional Javanese Designs

In many of his batik designs, however, Hadi worked within accepted and classical pattern categories, such as the plant and tendril pattern (semèn), the diagonal pattern (garis miring) and the grid pattern (ceplokan). His distinctive contribution lay in his ability to harness and transform these traditional motifs into symbols of contemporary political and social issues. In this exhibition, pairs of batiks have been displayed to illustrate the design in its classical form, and Hadi's unique interpretation.

The majority of Hadi's innovative designs take as their theme the role of the Javanese peasant. In a number of these designs, the images of classical temples and pavilions, and sacred landscapes of forests and mountains — all of which are associated with the semèn batik style — have been converted into elements representing the basic necessities of life. Hadi has integrated the everyday images of corn, rice, cotton-bolls and taro leaves into the traditional structure of classical and noble designs — the plant and tendril pattern and the diagonal pattern.

In The Peasants' Grid Pattern (Ceplok Tani) batik, the design of which is based on the Good fortune and prosperity pattern (sidå mukti) wedding batik, Hadi has replaced the familiar symbols of a glorious and prosperous future — the Hindu-derived images of temples, the sacred Mount Meru and the sun-wheel (cakra) — with peaked sunhats, crossed sickles and a lively interpretation of the village ox-cart as the peasant's chariot to the future Golden Age. In Hadi's work, these images become recurring symbols of agricultural abundance and the importance of the Javanese peasant.

The Utopian theme is most elaborately explored in a design entitled Srikandi as Goddess of the Indonesian Women's Movement (Srikandi Gerwani), in which Hadi has created a set of images of Srikandi — the legendary wife of the Mahabharata epic-hero Arjuna — a figure familiar to all devotees of the Javanese shadow-puppet theatre. In the flat, two-dimensional style of these wayang puppets, Srikandi appears in three guises: bejewelled and wearing the elegant skirt and breast wrap of a Javanese aristocrat; in the headcloth and long sleeves of a devout Moslem woman; and in the peasant garb of sunhat and striped homespun cloth. Thus, in these images, Srikandi appears to represent Javanese women of all social backgrounds. She also carries a book which Hadi used to symbolize literacy, a prominent aspect of the Indonesian Women's Movement rural reform programme. The cosmic tree mountain symbol (gunungan or kekayon) along the other side of this batik suggests the notion of change of scene or passage of time, just as it does when it is used in the wayang theatre.

The title of another design, NEFO, refers to a slogan popularized by President Sukarno, who was at that time President of the Republic of Indonesia. NEFO, an acronym for what Sukarno defined as the New Emerging Forces in world politics, was an ideological construct intended to counterbalance the strength of colonial and neo-colonial forces in the Third World. While the exact membership of Sukarno’s NEFO was never made explicit, Hadi’s batik design incorporates a number of symbols associated with some of Indonesia’s most prominent allies during that period, including the Chinese dragon, the Middle-Eastern winged horse and the Afro-Asian elephant. The raging Javanese bull, the banteng, which has been a prominent symbol of Indonesian nationalism, is also represented. The NEFO design is one of the few Hadi batiks which has obviously been influenced by north-coast batik designs. The structure of the design elements – flames leaping into a sparsely decorated field – was a popular style in the batik workshops of the Chinese communities of north-coast Java during the period. Unlike Hadi’s version, however, those batiks were noteworthy for their many vibrant colours derived from aniline dyes.

Hadi's batik-making career was brought to an abrupt end when an attempted coup in Jakarta, which took place on 30 September 1965, resulted in left-wing groups such as LEKRA being destroyed throughout Indonesia. Hadi was one of many members of the organization to be arrested. Although never formally charged or put on trial, he was held in a detention centre for political prisoners near Salatiga in central Java until 1976. After his arrest, his wife Sutrisni remarried and continued to produce batiks under her own name, using many of Hadi’s non-political designs. One example of these, The Ceremonial Ear Ornament Motif on a Striped Ground (Galar Sumping Dåråwati), is shown in the exhibition and is signed Trishadi, the workshop’s signature after 1965.

While he worked for only a short period in batik, Mohamad Hadi’s contribution to the history of the medium is nonetheless important, and represents one imaginative individual’s attempt to find a vital and continuing role for this traditional Indonesian art form. His work reveals a respect for the established traditions of Javanese culture as well as a strong social and political concern for the plight of the ordinary people, particularly the peasant farmers of rural Java.

Text sourced from: Maxwell, Robyn. Political Motives : The Batiks of Mohamad Hadi of Solo : Gallery 3A, 12 December 1987 to 5 June 1988. Canberra: Australian National Gallery, 1987.