Portrait Photography

9 Sep 1989 – 10 Dec 1989

Ansel Adams, Georgia O'Keeffe and Orville Cox, Canyon de Chelly National Monument, Arizona, 1937, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, Purchased 1980.

exhibition pamphlet essay

In the one hundred and fifty years since its invention, photography has dominated both public and private portraiture, and it is now difficult to imagine life without the photographs that define one's personal and social identity.

Before photography, only the relatively well-to-do could afford painted likenesses of themselves. With the development of William Henry Fox Talbot's negative and print process (patented in 1841), it became possible to make a number of photographic prints from a single negative, and by the 1850s portraiture was brought within the reach of the middle and lower classes. Photographic studios sprang up around the world, and professional portraiture emerged as a lucrative trade. Itinerant photographers in Australia and elsewhere travelled the countryside to increase their clientele and extend their business beyond the cities.

Technological developments at the turn of the century engendered further dramatic changes in the field of portraiture. The cameras and film processing services that George Eastman marketed for the amateur photographer initiated the era of snapshot photography. A favourite subject for these amateur photographers was, and still is, the informal portrait of family and friends. Formal portraiture, however, has remained the province of the professional photographer and the artist.

Posing for a portrait— for public and private reasons— is one of the rituals of modern life. Portraits mark one's passage through life in physical and social terms; they record the passing of time and also serve to define each person as an individual and a social being. In portraits made for private reasons, the subject is invariably a member of a family or social group, while in public portraiture the subject is either defined as a member of a larger social or professional organization or represents a purpose that extends beyond the individual.

This exhibition focuses on portraits made for the public domain, and includes photographs taken in Australia, the United States and Europe during the last one hundred years. Many of the photographs were made explicitly for commercial consumption and first appeared as reproductions in advertisements and (cover) illustrations in magazines. The show has been organized Ansel Adams according to commonly occurring groups: ethnographic portraiture, the self-portrait, the celebrity portrait, formal and informal portraiture, and the group portrait. In many of the works on display, the subject will be of primary interest, particularly when the portraits are of famous people, while in other cases the identity of the photographer will seem specially significant. Ansel Adams, for instance, who is best known for his landscape photographs, is represented here as a portraitist. But common to all the photographs in the exhibition are certain codes or conventions that determine the nature of portraiture.

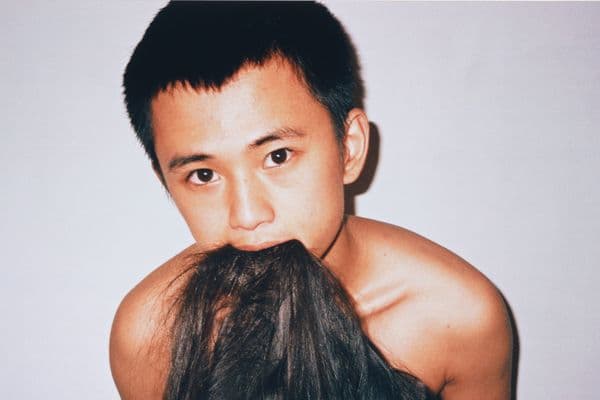

The conventions for photographic portraiture have remained remarkably consistent over the years. Firstly, and perhaps most importantly, is the unstated complicity that exists between photographer and subject as they work together to compose a suitable image. Studio photography has always dominated formal portraiture, and has its own dictates — the photographer is able to control the essential elements of setting, lighting and the pose of the sitter. Subjects are often presented in a spare studio environment where they face the camera and hence, later, the viewer. A favoured shot is the head and shoulders view that directs attention to the facial features.

In an effort to enliven the portraiture session and to create more 'revealing' portraits, some modern photographers have utilized informal settings and seemingly casual poses. However, even the strategy of informal portraiture has its own rules, with subjects invariably being framed in the medium distance. The inclusion of details of the subject's surroundings is a device that presents additional information about the individual. In recent years a number of artists have also experimented with the codes of portraiture by manipulating their images in a variety of ways.

The power of the photographic portrait is considerable. Since the early days of photography, audiences have been captivated by the ability of the medium to capture the physical presence of a person or object. As a result of this technical facility, the photographic portrait is alleged to be an objective description, and it has generally been assumed that photographic portraits are truthful in a way that painted or drawn portraits can never be: through the exact re-creation of external appearances, the inner self is revealed. This exhibition demonstrates, however, that every portrait is in fact a construction, and the extent to which it reveals the character of the sitter is a topic for endless debate.

Helen Ennis