William Kentridge

Drawn from Africa

17 Jan 2016 – 26 Jun 2016

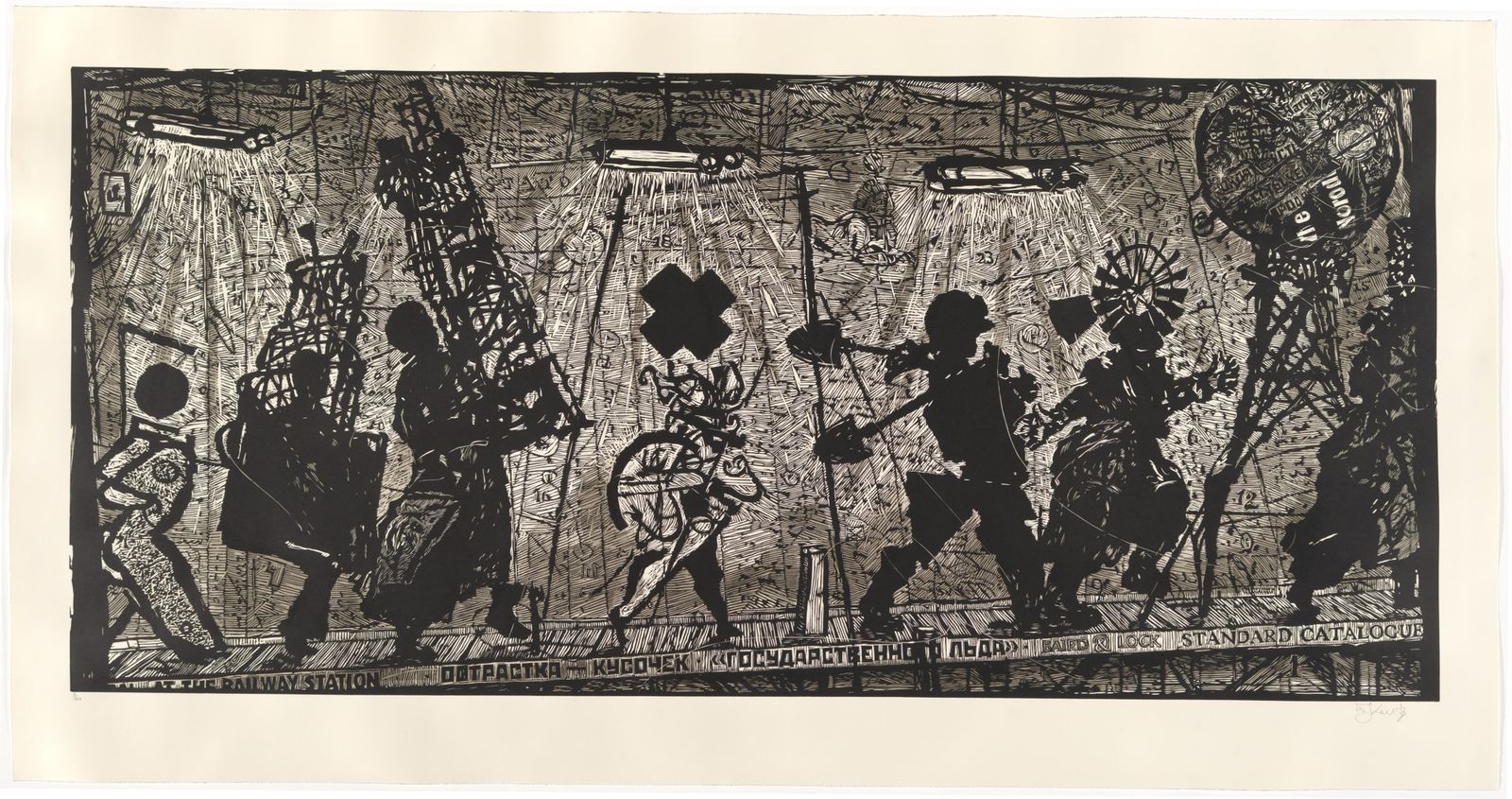

William Kentridge, Eight Figures, 2010, The Poynton Bequest 2013.

About

William Kentridge was born in apartheid South Africa in 1955. During his childhood, Kentridge's mother, Felicia, and father, Sydney, were both actively involved in supporting South Africa's anti-apartheid activists in political trials and in events such as the inquest into the Sharpeville massacre of 1960. His family's involvement in the injustices of apartheid played an important role in his development and informed his work as a gifted figurative artist. Given this background, Kentridge considered abstract art and conceptual art 'an impossible activity'.

Kentridge's art belongs to a tradition of some of the great figurative artists of the past such as William Hogarth, Francisco Goya and Honoré Daumier, as well as the German Expressionists Max Beckmann and George Grosz. These artists created powerful imagery that explored the social conditions of their time.

While Kentridge follows in their footsteps, he also develops imagery of subtlety and imagination in film, drawing, printmaking and tapestry design and explores three dimensions in innovative opera productions and sculptural forms. His art dismantles, transforms and fuses one art category into another.

The exhibition is accompanied by a short introductory video compiled from segments of the ART21 films, Anything Is Possible (2010) and William Kentridge: The Magic Flute (2011).

ART21, a non-profit art organisation based in New York, is internationally recognised for its outstanding documentary films and educational programs dedicated to contemporary art and artists. For further information, please visit ART21 Website.

This exhibition was sponsored by ABC Radio and IAS Museum Services.

Curator: Jane Kinsman, Senior Curator, International Prints, Drawings and Illustrated Books

Touring Dates and Venues

- Western Plains Cultural Centre, NSW | 31 January – 29 March 2015

- QUT Art Museum, QLD | 4 July – 6 September 2015

- Ian Potter Museum of Art, VIC | 20 October 2015 – 17 January 2016

- Art Gallery of Ballarat, VIC | 23 January – 10 April 2016

- Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery, TAS | 21 May - 26 June 2016

Essay

Emerging Artist

Early in his career Kentridge's art was overt in its criticism of the apartheid regime, as we see in Casspirs full of love 1989, published in 2000. The title of this drypoint and engraving is from one of the state radio greetings sent by families to their loved ones in the armed forces in which Kentridge heard a mother end her message 'from Mum, with Casspirs full of love', innocently meaning 'with truckloads of love'. Kentridge's use of the term, however, points to the reality that Casspirs had been the quintessential riot-control vehicle in South Africa, and that they had become a very real object, and symbol, of oppression.

Five years later, for his complex soft-ground etching, aquatint and drypoint Felix in exile 1994, Kentridge created a compilation of images found in the film Felix in exile of the same year, which draws on his experience as an acting student in Paris. His room is inspired by a painting by Kasimir Malevich. The imagery makes reference to the South African landscape and buried tortured history, which he left behind but remains with him while abroad. Kentridge says of this project, 'I am really interested in the terrain's hiding of its own history, and the correspondence this has … with the way memory works'.

In his art Kentridge often includes household items of his childhood, such as a manual typewriter or a Bakelite telephone or radio, as in the case of the charcoal and pastel drawing Bakelite radio 1994 – suggesting a nostalgic yearning for the memories of his early years with his close-knit family. In this instance the richly worked image of a Bakelite radio is shown bobbing along in a flowing river of luscious blue – the water permeating the city streets evoking the changing landscape of politics in 1994 when the apartheid regime was abandoned.

This rather whimsical drawing formed part of the hand-drawn animated music video of the song Another country of the same year, heralding the new era in South African society.

Kentridge has chosen to concentrate on old-fashioned technology rather than those from a digital age as they 'convey a more visible explanation of how they work. It's a mechanical rather than an electronic modus operandi, something in which you can see the cause and effect of switches, levers, wheels, visible mechanics … Even more than that, there is a sense of trusting childhood more than adulthood, that provides a reason for a lot of objects that I draw. These come from images of those objects that I saw in childhood'.

The Procession

Processions are a recurrent theme in Kentridge's shadow plays and films, as well as his prints, drawings and sculptures. Over the years Kentridge has created enigmatic scenes of processions, which are reminiscent of Dada theatre – a particular passion of the artist.

In various compositions we see a rich parade of figures (or a single figure) marching forward – a group of workers, fleeing refugees and performing actors proceed across a stage. These scenes are often theatrical and nonsensical and on occasion include a carefree female nude dancing around the dome, mourning figures in a funeral cortege or a man in a suit metamorphosing into a tree.

On parade, figures tramp across barren, degraded landscapes, thus avoiding what Kentridge terms 'the plague of the picturesque'. Alternatively, figures are seen running in circles around the apse-like form of a church or dancing along the proscenium of a stage. Some are weary and despondent, some exuberant, while others belong to the theatre of the absurd.

In the massive linocut Walking man 2000, Kentridge explores his interest in working on a grand scale on one single life-sized figure. Like some of Picasso's Vollard suite intaglio prints, this linocut may be inspired by the Latin poet Ovid's story of Daphne, who was chased by Apollo and transformed into a shrub. In Kentridge's contrasting and enigmatic version, we see a man in a striped suit with a middle-aged spread (recalling South African industrialist and property developer Soho Eckstein) stomping across a barren landscape with an occasional pylon, a remnant of its mining days.

The influence of the Soviet filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein is apparent in many of Kentridge's processional scenes, including Baggage I, II, II 2000. Images of people trudging over a landscape carrying arms or onerous luggage recall those found in Eisenstein's films, such as October 1927, which shows figures tramping across Petrograd (St Petersburg) in the revolution of 1917.

The massive linocut Eight figures 2010 is remarkable for its rich patterning and strong contrasts as well as its scale. In this work, Kentridge continued to explore a processional composition, which incorporates his experience as an actor and theatre designer. The nonsensical nature of this grand parade of figures is augmented by the artist's inclusion of random English and Russian signage below the stage on which the figures stride, providing a sense of the absurd.

Portrait of a Nose

One morning in St Petersburg, Collegiate Assessor Kovalyov – the key protagonist in Nikolai Gogol's short story The nose (Hoc) of 1836 – awoke to find his nose missing. Freed from the face of Kovalyov, the nose soon acquired the rank of State Councillor. In its elevated new role the nose now outranked its owner and considered Kovalyov unworthy of its attention and so ignored him, preferring to parade through the streets. This story was a perfect vehicle for Gogol to satirise Tsarist Russia of the 1830s – a time of despotism, terror, great bureaucracy and social stratification. For Kentridge, Gogol's fable was equally ideal in an exploration of the recent history of his homeland, which 'rings a bell with anyone from South Africa'.

In 2006 Kentridge produced a radical opera of The nose, originally composed by Dmitri Shostakovich in 1928 – a time in the USSR when, according to Kentridge, 'all music seemed possible'. Subsequently, over a three-year period, Kentridge created a series of 30 intaglio prints inspired by Gogol's tale. In the Nose portfolio, published in 2010, the artist experiments with and extends the notion of portraiture. Kentridge pervades the series with themes of hierarchy and confused identity, alluding to the history of Joseph Stalin's rise to power and the political purges of the 1930s in the USSR. In the series Kentridge marries the nonsensical and bureaucratic tyranny of Gogol's Tsarist Russia with that of the Stalinist regime and the recent damaging history of South Africa. He has done so in a jocular, absurdist manner that belies the tragedy of regimes both surreal and despotic.

In Nose, plate 18, Intelligence of the hand (Grigory Yevseyevich Zinoviev) 2009, Kentridge refers to the theme of the Great Stalinist Purges in one of a series of mug shots of Soviet political figures found guilty in the Show Trials. Initially, Zinoviev, a devotee of Lenin, sided with Stalin to destroy Trotsky. He was then arrested in December 1934 and two years later put on trial for treason as one of sixteen Old Bolsheviks. Kentridge's portrayal of the meek Zinoviev was based on a photograph of a curly-headed, almost boyish figure. For his etching, Kentridge papers over Zinoviev's nose, implying that he too is nose-less – politically impotent.

Portraits in Kentridge's rogues' gallery continue with another follower of Lenin in plate 19, Lev Borisovich Kamenev 2009. Kamenev's opposition to Stalin in the 1920s and overstated links with Trotsky led to his demise during the Great Purges of the 1930s. Unlike his associate Zinoviev, the more courageous Kamenev did not buckle as he faced certain death. Inspired by a photograph of this Old Bolshevik, Kentridge characterises Kamenev as a mature bearded man. His eyes and nose are not shown, covered by the absurdist legend 'Asleep'. Again, his nose-less features suggest Kamenev's political helplessness, while highlighting the grotesque nature of his fate.

Men who were part of the Central Committee of the USSR and survived the Great Purges also appear in Kentridge's line-up, including plate 20, Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Molotov. Molotov was adept in pleasing his political patron Stalin and was one of the original faceless men of politics. Perceived as a bland, featureless bureaucrat by many, Molotov outwardly developed a colourless non-descript personality, which belied his own cunning ambition and ruthless quest for power. Kentridge emphasises Molotov's characterless appearance by covering his face with a circle printed with the number 1. During the altercations between the USSR and Finland, the Finns applied his surname to a cheap incendiary device, the ironically titled Molotov cocktail, much to his distaste.

Kentridge continued the subject of the Nose in the linocut XA XA XA (Ha Ha Ha) 2010, which refers to the desperate experience of Nikolai Bukharin during Stalin's purges. This figure is the erudite Bolshevist theorist shown wearing a tweed suit (as opposed to the military outfit favoured by Stalin). Bukharin's political impotence is suggested by his missing nose papered over with the words 'Ha Ha Ha', which refers to the laughter that was the macabre response from the Central Committee in 1937 before Bukharin was executed. The juxtaposition of death and laughter is a chilling combination.

Magic Flute

With the 'family business' engaged in the defence of anti-apartheid activists during the years of white supremacy, Kentridge is ever mindful of the political and social issues in his homeland. His art is figurative because, 'Much of what was contemporary in Europe and America during the 1960s and 1970s seemed distant and incomprehensible to me … [it] became familiar from exhibitions and publications but the impulses behind the work did not make the trans-continental jump to South Africa'.

Kentridge's imagery is not overtly political. Its subtlety is evident in his drawing and subsequent prints relating to his production of Mozart's The magic flute. Kentridge's stage production of the opera was first performed in Brussels in 2005. In the artist's interpretation of the Mozart opera, Sarastro, the priest of light, 'combines all knowledge with all power', which he describes as a 'toxic mixture'. Kentridge notes that the opera was first performed at the height of the Enlightenment when it was at its 'most optimistic' and 'great certainty existed'. For his production, the artist reconfigured the opera, setting it at the time of German colonial rule in Namibia at the beginning of the twentieth century. This too was a period when belief and rule was all powerful. Here the high priest Sarastro plays the role of a colonial overlord. According to Kentridge, he 'combines certainty born of wisdom' and 'the right to a monopoly of violence', as witnessed in the tragic events of South-West Africa and later in the regimes of Joseph Stalin, Adolph Hitler and Pol Pot.

Kentridge chose the rhinoceros as the wildest of African beasts for his version of Mozart's opera, who was then tamed by the heavenly strains of the magic flute and tenor voice of Prince Tamino. Drawing for The magic flute (Tamino's rhinoceros) 2004 was one of the drawings that Kentridge filmed for the background of his production, where the beast prances and pirouettes in response to the dulcet tones of Tamino's aria.

A lightness of touch when dealing with complex and dark subjects is evident in the inventive print series Bird catching, which relates to his production of The magic flute. This imagery was projected on to the backdrop of the stage behind the performers of Mozart's opera. In this luscious group of intaglio works we observe swirling figures of birds along with the silhouette of the artist. These magical and apparently light-hearted images are a gentle reminder of ferocious activities of despots during the twentieth century.

Other Faces: Film & Landscape

From 1989 to 2003 William Kentridge created nine films about the life of Soho Eckstein, an industrialist and property developer living in contemporary South Africa. For the film Other faces 2011, the artist again returned to the fictional character of Eckstein for a film based on drawings he made over a twelve-month period. In the film we see Eckstein as a middle-aged figure dressed in a pinstriped suit, who on occasion looks remarkably like Kentridge (Eckstein's alter ego is Felix, a lover and poet, who also looks like the artist).

This cinematic animation opens with a car accident, where Eckstein collides with the car of a black African preacher and an argument ensues between the two drivers. An angry crowd forms in response. The sequence of images that follows suggests something of what it was like to live in South Africa after apartheid was disbanded in 1994. The accident becomes a metaphor for the political turmoil that still remained despite the fact that racial segregation and white rule had legally ceased. The film is set in inner Johannesburg and the barren landscape that surrounds the city, including a decrepit drive-in theatre seen in Drawing for the film Other faces (healing to all in global), all adding to the sense of social disruption.

Other faces is part recollection, part present day reality of the protagonist Eckstein. The film is sometimes stark and desolate, as shown in the scenes of the abandoned outskirts of the city or the scenes of the furious crowd in the Drawing for the film Other faces (protestors), a charcoal of 2011. Other images are poignant and tender, such as Eckstein's memories of his childhood, including the figure of his mother or his nanny. For the work Kentridge filmed a series of rich, textured charcoal drawings in stop action sequence – sometimes embellished with red pens and at other times rubbed out as the narrative ebbs and flows from past memories to contemporary events. The soundtrack was composed by musician Philip Miller.

Drawing for the film Other faces (large landscape) is a large-scale charcoal pastel and pencil landscape related to the film. It subverts the tradition of landscape painting by artists such as Paul Gauguin and the Pont-Aven painters, who created idealised landscapes, editing out the incursions of modern life. Kentridge's depiction of Johannesburg and its outskirts is the antithesis of this approach.

At first glance, the artist has created a lyrical view of the countryside on the eastern plateau of South Africa, rich in lush foliage and flowing waterways. Yet hidden among the grasses and woodlands are the remnants of the abandoned mining industry. The sad history is barely perceptible, a shadow, scarcely a memory. But it remains. For Kentridge, this wasteland drawing is a metaphor for the destructive effect of apartheid on his homeland in both the apartheid era and in contemporary life.

Throughout his career as he matured as an artist, Kentridge addressed political subjects but not in a strident way. There is a remarkable lightness of touch in his body of work, whether in film, drawing or printmaking, characterised by a subtlety enhanced by juxtaposition, metaphor, irony, humour and a sense of the absurd. This is evident in the travelling exhibition of Kentridge's art, William Kentridge: drawn from Africa, touring Australia in 2015 and 2016.

Jane Kinsman

Senior Curator, International Prints, Drawings and Illustrated Books