Collaboration and chosen family in Peter Tully’s practice

Peter Tully, Tony's vest 1987, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, gift of Tony Guthrie 1990 Courtesy of copyright owner, Merlene Gibson (sister)

With a focus on the powerful influence travelling can have on artists, TARA GOUTTMAN reflects on PETER TULLY and the idea of chosen family and its intrinsic importance for queer identity.

‘[The group] were scholarly and thorough, and they had a whale of a time while they dissected ideas and the patterns of garments’1

The people we surround ourselves with say a lot about us: who we are, what we believe in, what we stand for and what inspires us. Peter Tully, artist and artistic director of the Sydney Mardi Gras from 1982 until 1986, surrounded himself with like-minded people who encouraged one another to seize each day and live unapologetically during a time when gay and feminist movements were gaining serious momentum. His chosen family—designer Linda Jackson, photographer and Jackson’s partner at the time Fran Moore, artist David McDiarmid, designer Jenny Kee and photographer William Yang—all dipped and weaved in the wider circles of fashion, politics, art and design.

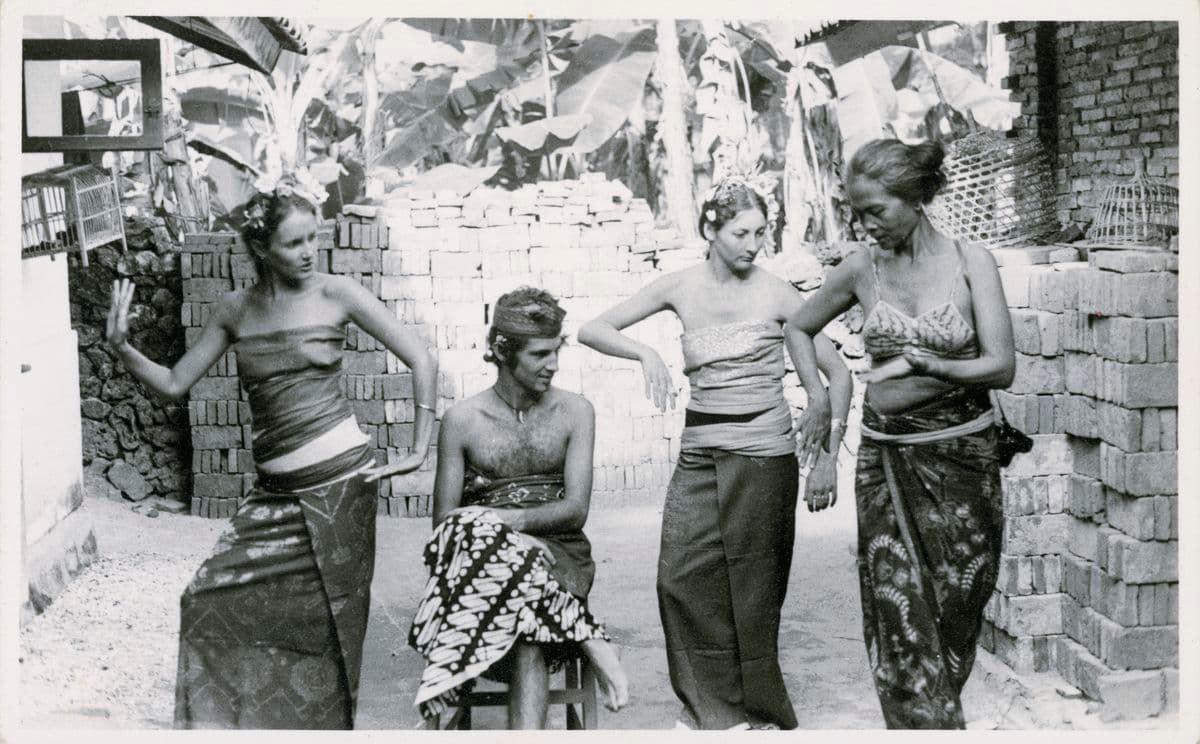

Linda Jackson, Peter Tully and a friend at Kuta Beach, Bali, Indonesia, being taught to dance by Elder Ibu, 1971, Linda Jackson archive, photo: Fran Moore © Fran Moore/Copyright Agency, 2025

The impact of Jackson on Tully’s artistic practice and personal life is particularly significant. In 1970 he accompanied Jackson and Moore to Lae in Papua New Guinea where they resided for a year. Tully eventually split off from the pair, teaching English in Paris and taking short trips to Western Europe to destinations like Spain and the Netherlands.

In the 1980s, Paris was a significant historical and cultural hub — home to expansive museums and gallery collections that far surpassed the content publicly available in Australia. The Oceanic and African objects in Paris collections captivated and intrigued Tully, so much so that before reuniting with Moore and Jackson in 1973 to return to Australia, he travelled the long way, through Sudan, Ethiopia, India, Egypt and Kenya. It was during these extensive travels that Tully was exposed to different methods and artmaking practices that were unfamiliar to most Australian artists.

His work Tony’s vest 1987 shows some of the found objects and pendants that he collected during his travels including feathers, shells, teeth, pop-culture pins and decorated buttons. Tully’s time in Sudan and the use of non-precious materials in jewellery making deeply resonated with him. In Tony’s vest he applies his observations, combining modern souvenirs of New York City and Australia with African talismanic adornments and ideas. Here, Tully emphasises his own gay ‘tribe’. He highlights the ties he felt to communities across the globe and the celebratory queer space that he helped create within Australian fashion. By forging playful, creative and vibrant parallels between these groups—each existing on opposite sides of the world—Tully’s sartorial artistic manner celebrates non-exclusive notions of art, fashion and political identity.

Peter Tully, Tony's vest, 1987, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, gift of Tony Guthrie 1990 Courtesy of copyright owner, Merlene Gibson (sister)

These overseas influences also reveal themselves in the collaborations Tully shared with his chosen family. In 1975, Kee and Jackson’s annual Flamingo Follies fashion parade for their brand Flamingo Park Frock Salon demonstrated an ambitious collection of collaborations between the group. Kee and Jackson made all the outfits for the parades, then Tully would make jewellery inspired by the outfits to accompany them. McDiamird would sometimes hand paint the fabrics Kee and Jackson would use, while Yang would document the events through photography. This is how the collaborative element came to life among the group, and it was not simply restricted to Flamingo Follie events. Wearable pieces by both Tully and McDiarmid were championed by the brand’s founders and sold at the store's location in the Strand Arcade, Sydney. Many of these accessories survive, such as Tully’s Uluru brooch 1980, a stylised map made from fluorescent plastic that recognises Uluru as the heart of Australia.

It is difficult to discuss Tully and Jackson without mentioning the wider friendship group that was an important catalyst for their artistic creation, exchange and collaboration. This concept of chosen family remains an essential aspect of many queer lives today. These bonds are often a transformative, liberating and healing aspect of queer identity. They demonstrate an all-encompassing level of mutual love, encouragement and support that individuals may not receive in their obligated familial relationships.

William Yang, Group at Peter and David's exhibition, Hogarth Galleries, Paddington 1977, State Library of NSW, purchased 2022 © William Yang/Copyright Agency, 2025

The group, while using cheap, inconspicuous and easily accessible materials, brushed away conformist traditions and cultural norms, becoming figureheads of the Australian sexual revolution and gay liberation cultural politics. It was through his chosen family's support, companionship and collaborative creative endeavours that Tully was able to leave such a significant imprint in Australian queer politics and art historical understandings.

- Judith Pugh, ‘An era that changed us’, Artist Profile, 2017, https://artistprofile.com.au/an-era-that-changed-us/

This story is part of the 2024 Young Writers Digital Residency.