Ansel Adams and American Landscape Photography

20 Sep 1986 – 1 Feb 1987

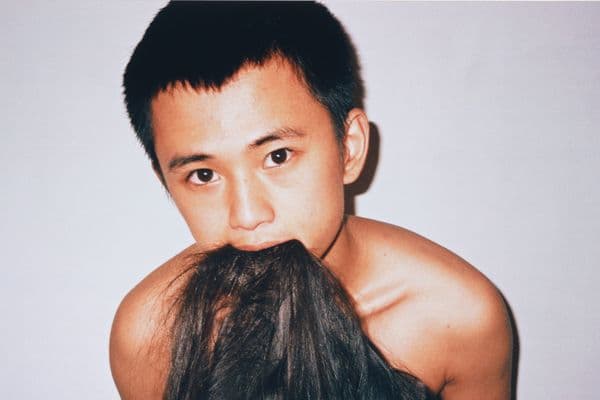

Ansel Adams, Muir Pass, The Black Giant, 1930, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, Purchased 1987.

About

This exhibition brings together images of the American landscape by a group of twentieth-century photographers. Although their work is diverse and embodies a range of approaches to both the landscape and photography, the photographers have in common a deliberate way of working, which is evident in their choices of what to photograph and how to present it. There is a shared emphasis on technique, with the well-crafted print (from a first-rate negative) being regarded as an expressive form of art.

Through their diversity the photographs on display suggest that ‘landscape’ is as much a concept as a place. Because attitudes to the landscape are constantly changing, in terms of land usage and the meanings carried in works of art that have the land as their subject matter, the photographs in the exhibition evoke in turn romantic, mystical and quite ordinary worlds.

Exhibition Pamphlet Essay

Ansel Adams grew up on the outskirts of San Francisco and, as a youth, hiked and photographed in the spectacular Sierra Nevada mountain range in the Yosemite National Park, California. His vision, first expressed in the 1920s in photographs of the Yosemite area, remained essentially unchanged in six decades.

During his long career, Adams photographed extensively in California and the southwestern states, particularly Arizona and New Mexico. Typically, he chose sites which gave grand uninterrupted views and which often required considerable physical effort to reach. Rarely are people, or signs of their presence, to be seen in his photographs.

Adams’s images express a boundless faith in the glories of nature. His vast, towering landforms dwarf the spectator, and he often photographed during storms or at sunset to heighten the natural drama of the landscape. Even small details of the natural world, like dew-laden leaves, are shown to be monumental through the effects of light.

While Adams's photographs are often seen to be rooted in nineteenth-century conceptions of God, Man and Nature, they are, in fact, the product of a concern for conservation, a critical issue of this century. The landscape in Adams's photographs is not one to be conquered and domesticated by exploration, farming, mining or urban development. Rather, it is an awesome wilderness to be respected and preserved. With the natural environment increasingly under threat, Adams believed that national parks and wilderness areas provided people with a vital and essential opportunity for the contemplation of beauty.

Throughout his life Adams was active in the conservation movement, and his photographs were frequently published by the Sierra Club, which he joined in 1919. His photographs of the Kings Canyon area were used to persuade the U.S. Congress to declare the area a National Park in 1940. In his last years Adams spoke out against the administration of U.S. President Ronald Reagan for its neglect of major environmental issues.

While the subject matter of Adams's photographs has ensured their popularity, they have also been praised for their technique. Adams was one of the champions of what we call 'straight' photography, that is, sharp-focus, unmanipulated photographs.

He developed the Zone System, which enables the photographer, through correct exposure of the negative, to secure a wide tonal range in the print. Adams was very influential as both a teacher and an author and also enjoyed a successful commercial career.

The Ansel Adams photographs on display are principally modern prints from early negatives. They were produced by Adams in the mid-1970s and early 1980s with the help of darkroom assistants. The three vintage prints in the exhibition (printed soon after the negative was taken), provide a fascinating comparison. They are smaller in scale and lighter in appearance, lacking the dramatic tonal contrasts which he deliberately sought in the later prints.

Two of Adams's colleagues in Group f.64, which was founded in 1932 to promote straight photography, were Californian photographers Imogen Cunningham and Edward Weston. Cunningham is represented in the exhibition by a sensual, close-up photograph which pictures a detail of nature — a magnolia flower.

The two photographs by Weston are of Point Lobos on the Californian coast, an area he photographed over many years. Weston worked with an 8" x 10" camera, which produced large-format negatives, from which he made contact prints rather than enlargements. His prints are sharp and detailed, and render the surface texture of natural forms, whether rock, wood or sand. The photographs on display were printed under Weston's supervision by his son Brett. Brett Weston is also a well-known photographer and two of his works from the 1960s are included in the exhibition.

In the photographs of Minor White and Wynn Bullock location is irrelevant. They find in the landscape elements which mirror or serve as equivalents of their psychological states. The photographs of both artists are dark and moody, suggesting symbolic readings.

Paul Caponigro, who studied under Minor White, produces intimate landscape photographs which seem to be more human in scale. He favours close-up and medium-distance views, and rarely uses the long shot. Caponigro also has a strong sense of graphic design and his details of nature are abstracted into spare compositions. Similarly, Harry Callahan's studies of blades of grass and tree foliage stem from an interest in the abstract forms of nature.

During the 1970s some artists, such as William Clift, continued to express an essentially romantic vision of nature. Clift has worked largely in the southwestern United States, choosing sites which were often photographed by nineteenth-century photographers like T.H. O'Sullivan, and more recently by Ansel Adams and others. His photographs are finely printed and he uses a variety of chemical toners to subtly determine print colour.

However, by the seventies, many American photographers had become dissatisfied with the grand and mystical visions of their predecessors. Those who became loosely known as the New Topographers (after an exhibition New Topographics at the International Museum of Photography in Rochester, New York, in 1975), turned away from the untouched natural world to an altered landscape. Their point of view seems casual, with their photographs often being taken from the side of the road. Their subjects are commonplace.

One of the major photographers working in this style was Robert Adams. In photographs published in the books The New West, and The Missouri West, Adams included the signs of human presence; the roads, powerlines, building sites and houses. The West is no longer wild but has become domesticated, ordinary, and often spoilt.

The views of Robert Adams and Lewis Baltz are delineated in a deadpan style which is contrary to the heroic tone used by Ansel Adams, William Clift and others. While the photographs seem more objective (like maps), and the photographer seems less conspicuous, it must be emphasized that the photographer has nevertheless created his images by conscious decisions — both about what to photograph and how to do it. The results are personal statements, encoded in the cool rhetoric of the mid-1970s, the era of minimal and pop art.

William Eggleston's colour photographs are executed in an equally non-dramatic style. He pictures the areas he knows best, the expansive, flat lands of his home state, Tennessee. He takes as his subjects the ordinary, and often unattractive, aspects of this landscape — roads, fields and the straggly rural/urban fringes — and finds within them a beauty which is generally not recognized. He also enjoys the effect that colour processes have on his work.

The exhibition also includes images of the landscape in which the artist's intervention is obvious and declared. John Pfahl places his sculptured or painted objects in the landscape before he takes his witty photographs. Rick Dingus draws on the surface of his prints. Mark Klett writes on his negatives, paying homage to nineteenth-century scientific photographs, where factual details are given alongside the images.

While all the photographs are of America they do not present a single, static view of the American landscape. On the contrary, they explore a subject which is constantly being defined and re-defined, depending on current approaches to both landscape and photography.