Country + Constellations

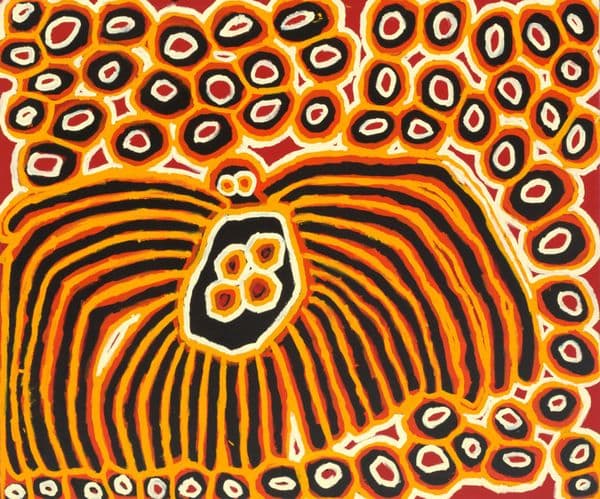

Daniel Walbidi, Mangala/Yulparija peoples, Wirnpa 2011, synthetic polymer paint on linen, the Wesfarmers Collection of Australian Art, Boorloo/Perth, © Daniel Walbidi/Copyright Agency, 2022

immemorial

adjective

extending back beyond memory, record, or knowledge

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have always been and always will be part of this country. There is deep time evidence of our presence in the landscape, from mark-making in the ground, on trees or in caves, to sacred burial sites and ceremonial grounds. Indigenous people use trees to make shelters, funerary poles and posts, they hammered and engraved age-old designs into rock and made sophisticated fish traps. Rock art galleries are filled with painted representations of Ancestors, animals, the outlines of hands, weapons and even encounters with strangers in ships.

Traditional designs are carved into trees to delineate ceremonial areas or significant sites, and outline scars on trees record the removal of bark and wood to make shields, containers, boomerangs and clubs. The creation of stone tools at quarry sites, the mining of ochres and clays at specific pits, and layered shell middens containing evidence of gathering habits and foods eaten all demonstrate Indigenous peoples’ ongoing existence and continued occupation of and connection to Country.

Australia’s First Peoples were also the world’s earliest agriculturists, using fire to regulate the environment and create favourable conditions for the growth of certain plants and animals as well as natural harvesting sites for food. These practices are still in use and are depicted in art.

Returning to Country is essential for many artists. It is a means of reconnection and an opportunity to renew and repaint rock art and to source materials for their work, such as ochre, clay, plants and animal parts. Our Country is us and we are our Country. This intimate connection to and knowledge of Country also informs our links to the constellations and stars. The stars help us navigate the land, inland waterways and oceans, and teach us about creation stories. They are like maps, directing us to certain landscapes, informing us when seasons are about to change, when certain hunting and gathering activities should occur, and when animals and plants are ready for harvest. The stars are inseparable from Country and people.

Daniel Walbidi

'Winpa is an Ancestral rainmaker. To desert people water is very important—it’s the source of life, our stories are centred around water.

‘Ancestors are connected to places like Winpa and many other places … Winpa is an Ancestor who travelled to many places as far away as the goldfields, across the border to Central Australia. He came back to his Country and laid down to rest, then he became Winpa.

‘I tried to capture the Country around Winpa, like the white salt lakes, sandhills and the water … I used yellows to depict the desert. Growing up on the coast inspired me to use the blues, reflecting the coastal influence.’

Winpa is the Ancestor who created the jila (waterholes). Winpa travelled across Country, meeting up with other Ancestral beings. Winpa was a hunter and rainmaker who had many sons. The waterholes are Winpa and his sons.

Daniel Walbidi is a Mangala/Yulparitja man born in 1983 at Bidyadanga/La Grange Mission on the Western Australian coast. He grew up hearing the Dreaming stories of living water created by Winpa and celebrates the mayi (bush food) with an abundance of colour.

Walbidi spent time with his Elders at Bidyadanga to ensure their stories would be documented through painting. Taking a helicopter flight with the senior Yulparitja artists, returning to Inpa and Kirriwirri (Walbidi’s father’s Country), Walbidi saw the land from the air. The central waterhole is connected to the underground creeks in the landscape. For the first time the men sat on Country together, reacquainted themselves with their Ancestors and painted the Dreaming stories—an emotional experience for all.

Daniel Walbidi, Mangala/Yulparija peoples, Wirnpa 2011, synthetic polymer paint on linen, the Wesfarmers Collection of Australian Art, Boorloo/Perth, © Daniel Walbidi/Copyright Agency, 2022

Look

What angle is the view of Walbidi’s Country taken from? Can you find the waterhole and the mayi (bush food) in this image?

Why do you think there are so many colours represented?

When creating Winpa 2011, what technique has Walbidi used to apply the paint?

Think

Have you been in an aeroplane and looked down on the landscape? What does it look like and how does it make you feel?

Why is Country important to Walbidi and his family?

Create

Think of a journey you take between your home and somewhere nearby of significance to you. It might be your friend’s or a grandparent’s place, to a sports or arts venue, or even your school or local shops. Develop your own mark-making technique and symbols to represent the journey and places along the way. What colours will you use to tell the story of your journey? Is there a special place you go that you do not want anyone to know about? How might you hide this special place within your artwork?

Jonathan Jones

‘untitled (walam-wunga.galang) is a collaborative project with Uncle Stan Grant Senior and Beatrice Murray. It celebrates the south-east cultural practice of collecting seeds, grinding them to make flour, to make bread, feeding our families. This practice has occurred for countless generations in this region. A grindstone believed to be 32,000 years old was unearthed in central New South Wales, making us some of the world’s oldest bread-makers. The works are made from sandstone collected from the south-east, slowly ground down over years. The process of shaping stone with stone speaks to our enduring presence and the strength of our knowledges.’

'In the soundscape we hear Uncle Stan Grant Senior speak to us in Wiradjuri, telling us to stay connected to Country, that Country needs us, and that if we look after it, Country will look after us. ngangaanhi ngurambang wiinydhuradhu (we care for our Country with fire), speaks to the importance of fire to maintain Country and encourage cereal grasses. Beatrice Murray sings Uncle Stan’s words to life, reminding us of the cultural significance of the links between our creative processes and caring for Country, for our grasses, our objects, which have sustained our communities for thousands of generations. These stories and how we tell them are what makes a nation.'

Jonathan Jones is a Wiradjuri and Kamilaroi artist, born in 1978 in Gadigal Nura/Sydney where he lives and works. He works across a range of mediums including film, printmaking, drawing, sculpture and installation as he interrogates cultural and historical relationships and explores Aboriginal perspectives.

untitled (walam-wunga.galang) is inspired by the fact that native grasses were carefully cultivated and collected to make bread to sustain First Nations peoples in Australia for at least 32,000 years.

Jones strives to remember the past in the present through his work. He feels that being an artist is a group effort, acknowledging the research and cultural maintenance of those who inspire him, bringing forth cultural identity and deep ties to Country.

Jonathan Jones, Wiradjuri/Kamilaroi Peoples, untitled (walam-wunga.galang) (detail), 2020–21, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased with the assistance of Wesfarmers 2020 © Jonathan Jones

Look

What materials has Jones used to make these large sculptures? What do you notice about them?

Think

Why is it important to know that First Nations people were grinding seeds for bread-making tens of thousands of years ago?

Create

Research a native plant that produces grains and is ground to become food. Draw the progression of the plant from seed to food and create natural prints on paper. You might even be able to find these seeds, or the seeds of other non-native plants and try grinding them to understand the process.