Innovation + Identity

Michael Riley, Wiradjuri/Kamilaroi peoples, Untitled, from the series cloud [boomerang] 2000, printed 2005, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2005, reproduced courtesy of the Michael Riley Foundation/Copyright Agency.

forever

adverb

without ever ending; eternally

continually; incessantly; always

lasting for an endless period of time

As the First Peoples of the continent called Australia, innovation is at the heart of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people lives. Through innovation, we have adapted and incorporated new ways of living in order to survive.

One of our most important and ground-breaking innovations—and one of the most recognisable and iconic Aboriginal symbols—is the boomerang. The returning boomerang is one of the world’s first examples of a human-made flying object. For a perceived primitive society, Australia’s Indigenous peoples have been first in many fields—the first doctors, scientists, astronomers, engineers, horticulturalists, farmers, fishermen, designers, physicists and artists. We have always used creativity and ingenuity to adapt and overcome.

Identity is one aspect of Indigenous artists’ expression. The artists in this exhibition tell stories through their work about identity and culture in many different ways. Their art is a powerful reflection of themselves and gives a voice to their communities. Working across a range of mediums and using traditional and innovative materials, their work is recognised nationally and internationally.

It is important for Indigenous artists to express their identity on their own terms. It is a personal journey and not one that can be dictated by society. Art is a platform to explore and challenge this aspect of their lives. Regardless of how they identify, their art speaks for them and their communities, and is a meaningful, lasting, ever-present legacy.

Michael Riley

‘I was always interested in seeing things around me differently. I remember lying down in the front yard one day looking up at the telegraph poles and lines, the power cables going across, cutting across the sky and almost cutting through the clouds; looking at it and isolating it; looking at the simplicity and at things in depth and from a different perspective.’

Michael Riley (1960–2004), a Wiradjuri and Kamilaroi artist, was born in Dubbo, New South Wales, on the Talbragar Reserve. He photographed Dubbo and Moree, where his parents were from, giving a rare insight into their rural lives that reflects his perspective on Aboriginal societies in a universal language.

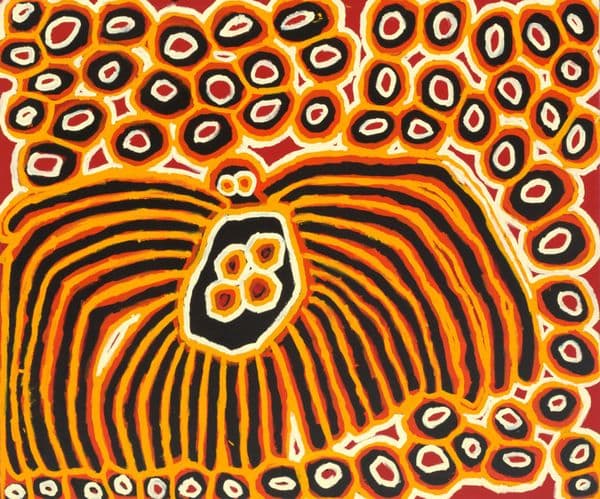

Riley challenged the western perspective perspective of Aboriginal art through photography and film. The boomerang highlights the sophistication of Aboriginal cultures and understanding of physics. Riley’s series cloud 2000 cleverly presents symbols to convey ignorance and wrongs of the past.

Born on his Country, he moved to Gadigal Nura/Sydney as a teen and consolidated his artistic practice in photography. With nine other First Nations artists, he was a co-founder of the Boomalli Aboriginal Artists Cooperative in Chippendale in 1987 and a role model for many First Nations artists.

The otherness, the making—that is, the story—is important in his art.

Michael Riley, Wiradjuri/Kamilaroi peoples, Untitled, from the series cloud [boomerang] 2000, printed 2005, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2005, reproduced courtesy of the Michael Riley Foundation/Copyright Agency.

Look

What do you notice about Riley’s work of art?

Think

Riley challenges western understandings of Aboriginal art. Why do you think Riley chose to depict the iconic boomerang in this way?

Create

The boomerang is a sophisticated tool linked to traditional knowledge of aerodynamics and flight. What shapes could you invent that have a unique purpose? Represent your invention in an art piece.

Sandra Hill

'No matter what colour we are – we are all in this together. We are all joined by blood and humanity.'

Sandra Hill is a Minang/Wardandi/Ballardong/Nyoongar artist, born in Boorloo/Perth in 1951. As a young girl in 1958, Hill was forcibly removed from her mother’s care and the third generation of her family to be part of the Stolen Generations. After reconnecting with her mother after 27 years, she learned that her mum worked as a domestic servant in non-Aboriginal homes. Many of these experiences and stories inspired her art and encouraged a journey of self-healing.

sKIN Deep 2015 explores racism, kinship and healing, addressing the female perspective and the experience of Aboriginal women. Using metaphoric gestures through mission craft sewing, she evokes her matriarchal lineage. The aesthetic and act of stitching paper together references a time when Aboriginal people made clothing, among other objects, with unwanted or unused materials such as potato sacks or calico fabric.

Hill says, ‘If I hadn’t had the healing process of telling my stories through art, I can't imagine where I would be or what condition I’d be in’.

Sandra Hill, sKIN deep 2015, the Wesfarmers Collection, Boorloo/Perth

Look

Hill is part of the Minang/Wardandi/Ballardong/Nyoongar peoples. Find her Country on the map.

What do you notice about Hill’s work of art?

Think

What do you think the coloured square and rectangular shapes might symbolise?

What do you notice about the way the artist has represented the words and letters in this work? What is the significance of calling this work sKIN deep?

Create

Create a work of art to represent your family connections and relationships. What shapes, colours and materials might you use to tell your story visually?