Resistance + Colonisation

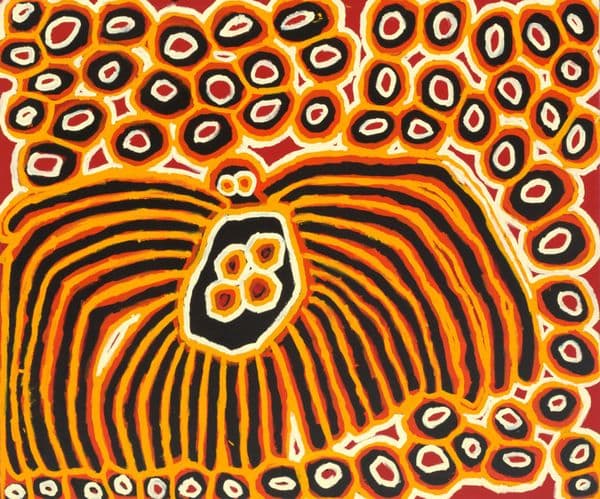

Danie Mellor, Mamu/Ngadjon peoples, Of dreams the parting 2007, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2008

eternal

adjective

without beginning or end; lasting forever; always existing

perpetual; ceaseless

enduring; immutable

‘All Aboriginal art is political because it is a statement of cultural survival.’

Gary Foley, 1984, broadcast on The Point (television series), NITV 2020

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are fierce protectors of their people, culture and Country. The resolute defiance of the early Indigenous warriors and Elders who resisted the colonisation of Australia is what inspires present-day activists, agitators and leaders at the forefront of recognition and change. Australia has a shared history, but Indigenous experience has for too long been contested or denied—a situation that artists have helped to expose and change.

For many First Nations artists whose culture, language, Country and family have been taken from them since first contact, the ongoing effects of violent frontier encounters and government policies forcing their integration, assimilation or removal have been important subject matters for their works. Their art highlights the social and political injustices of the past and present. Artists have mined archives and used the official writings of governments and colonists to reveal the hidden histories of their deliberate acts of incursion, theft and massacres, bearing witness to and telling the truth of Australia’s history.

Judy Watson

‘Blue is the colour of memory and is associated with water; it washes over me. Waanyi people are known as running-water people because of the inherent quality of the water in their country.’

Judy Watson was born in Mundubbera, Queensland, in 1959 and spent time exploring her great-grandmother's Waanyi Country in northwest Queensland. This link is central to her art practice.

Watson seeks the hidden histories and impressions of Aboriginal women’s experiences. Past presence on the landscape is sought through the rubbings, incisions and engravings on Country, which she reveals subtly.

Blue is an important colour to Watson and a key part of her work. It’s also the colour of the coloniser, in uniforms and flags—another subject frequently used in her work.

In stake 2010, Watson uses bright white to highlight three ambiguous shapes on a base of iridescent blue pigment wash. The work can be read in different ways; from an Aboriginal or coloniser perspective.

The work signifies the military and the open wounds inflicted on Aboriginal people. It is a strong counter-reference to the colonial experience through the expression of Aboriginal connection to Country, culture and presence in landscape.

Judy Watson, stake 2010, the Wesfarmers Collection, Perth © Judy Watson/Copyright Agency, 2022

Look

Look at the colours and mark-making in Watson's work. Can you identify what she is conveying?

Think

Consider the environments that are special to you—your home, school, local park or playground. What memories do these places hold for you?

Create

Make a series of rubbings that record the textures of your environment. Start by placing paper over the object then turn your pencil horizontally and shade/pencil over the texture.

Create a series of made and natural objects. Use different colours, or even natural colours.

Danie Mellor

‘Cut from travelling trunks, the Balan Bigin/shields (Jirrbal/Mamu dialect) in this series reference and symbolise voyages, arrivals, departures, moving on, presence, displacement and even adventure. Shaped and sculpted to echo the shape and size of rainforest shields from the Atherton Tablelands area, they recall a time in memory, authenticated by their apparent age.

The appearance and form relate to the projected identity of those who dressed in a particular way for photographic portraits ... the Victorian and buttoned dresses that women in our family wore, for instance, speak of a westernised persona, which seemed incongruent in some ways given they were Indigenous women. This dovetails with the notion of identity and matrilineal heritage in this context: the shield in rainforest culture is seen as a feminine object.’

Danie Mellor, born 1971 in Mackay, is from the Mamu and Ngadjon peoples of the Atherton Tablelands in Northern Queensland and also has Scottish heritage. Mellor explores the impact colonisation has had on the landscape and he observes the intersection of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal cultural perspectives and experiences in Australia’s shared post-settlement history. Mellor’s own cultural Ancestry is a mix of these tensions.

Mellor reclaims rusty old metal travelling trunks to repurpose them as metal shields in Of dreams the parting 2007. Travelling trunks carry the objects, clothes and personal items for the person/people moving from one part of the globe to the other. The colonisers were afforded the luxury of transporting their worlds with them in these travelling trunks as they arrived in the new land of terra nullius. Shields symbolise identity and protection as well as kinship and pride. The symbolism of the trunk is dislocation and passage.

Danie Mellor, Mamu/Ngadjon peoples, Of dreams the parting 2007, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2008

Look

What can you see in Mellor’s work Of dreams the parting?

How have the suitcases been transformed?

Think

In what situations do people use shields? What do you think shields symbolise?

Why might Mellor have transformed these suitcases in this way?

What story is Mellor telling us and why is this important?

Create

Can you think of a time when you have overcome a challenge in your life, big or small? Create your own work of art centred around a symbol that represents this journey for you.

Julie Gough

'This artwork contains part of me and my family. We come from Aboriginal people removed from Country and family in Van Diemen’s Land in the early 1800s ... I have a list of 209 children, including one of my Ancestors and her two sisters, compiled over the past decade ...

‘This artwork consists of unfinished tea-tree spears held within the framework of an old chair whose legs are burnt … The chair holds the children captive, but together, united ... These spears are raw tea tree sticks ... each has a section peeled away … where I have burnt the name of one of these lost children ... of about one-third of the children I am seeking.’

Julie Gough is a Trawlwoolway artist born in 1965 in Nipaluna/Hobart in lutruwita/Tasmania. She is interested in why Van Diemen’s Land was renamed Tasmania in 1856. First a penal colony in 1803, it was firmly established by the British by 1824, despite Aboriginal people being present.

Gough uses found and constructed objects and narratives of historical events. Some Tasmanian Aboriginal children living with non-Aboriginal people before 1840 2008 juxtaposes the seatless historical European chair, unable to be grounded and transforming its use as container, and 83 tea tree spears each with the name of a stolen Aboriginal child burnt into it, bunched together and restricted.

Like a detective, Gough trawled through archives and oral histories, uncovering accounts that lead to truth-telling. As she explores her genealogy, Gough invites the viewer to understand our continuing role in, and proximity to, unresolved national stories—narratives of memory, time, absence, relocation and representation.

Julie Gough, Trawlwoolway people, Some Tasmanian Aboriginal children living with non-Aboriginal people before 1840, 2008, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2008 © Julie Gough/Copyright Agency, 2022

Look

What do you notice about Gough's work?

Think

In Gough’s work of art, the legs of the chair do not meet the ground, what could this symbolise? What does the title of this work mean in relation to the objects Gough has repurposed?

Create

Investigate a hidden history you might not have learned in school about the First Nations people of your region. You might centre your research on how First Nations people have resisted colonisation. Create a poetic response on what you uncover.

Michael Cook

‘Undiscovered is a photographic project that reflects upon European settlement in Australia. This moment was presented in history as the discovery of Australia, despite the fact Aboriginal peoples had been living here for thousands of years.

‘The new British settlers had no idea of the basis and meaning of Aboriginal culture prior to their arrival. Aboriginal peoples were seen as inferior, with no education or organisation; their knowledge and experience of the land was ignored.

‘Undiscovered is a contemporary look at European settlement in Australia, a land already populated by its original peoples.’

Michael Cook is a Bidjara artist of southwest Queensland. As a photo media artist who explores identity, he restages colonial views of history and re-imagines a contemporary reality for Aboriginal people.

The Undiscovered 2010 is seen through the eyes of a young Aboriginal woman reflecting on the British invasion of Australia.

In Undiscovered #3 2010, we see the recurring Aboriginal man, his role reversed. Accompanied by a kangaroo at the shore, he is dressed as a British coloniser and holds a musket as he stands on a ladder. The central idea is: what if the British, instead of completely and summarily dismissing Aboriginal people, took a more open approach to them, their culture and their knowledge systems?

By depicting Aboriginal people in roles diametrically opposed to those we are accustomed to, Cook ensures his work is recognised as an Aboriginal dialogue and an Aboriginal voice is ever-present. He says, ‘This is an important work—it will live on when I’m gone’.

Michael Cook, Bidjara People, Undiscovered #3 2010, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2010 © the artist and This Is No Fantasy

Look

Look at the figure of the man in the painting. What do you notice about him? What clothing is he wearing? Why might he be holding a musket and standing on a ladder by the ocean?

Think

Is Cook thinking, dreaming or remembering something in this work?

What do you think the term undiscovered means to the artist?

Create

Through his art, Cook challenges perspectives on Australia’s foundations. Tell a story in the form of an art piece that challenges the dominant narratives you’ve learnt about a topic.