Artists' Artists: Danie Mellor

Danie Mellor, Mamu/Ngadjon peoples, An Elysian city (of Picturesque Landscapes and Memory), 2010, purchased 2011

Artist DANIE MELLOR discusses works from the national collection that inspire, move or intrigue him.

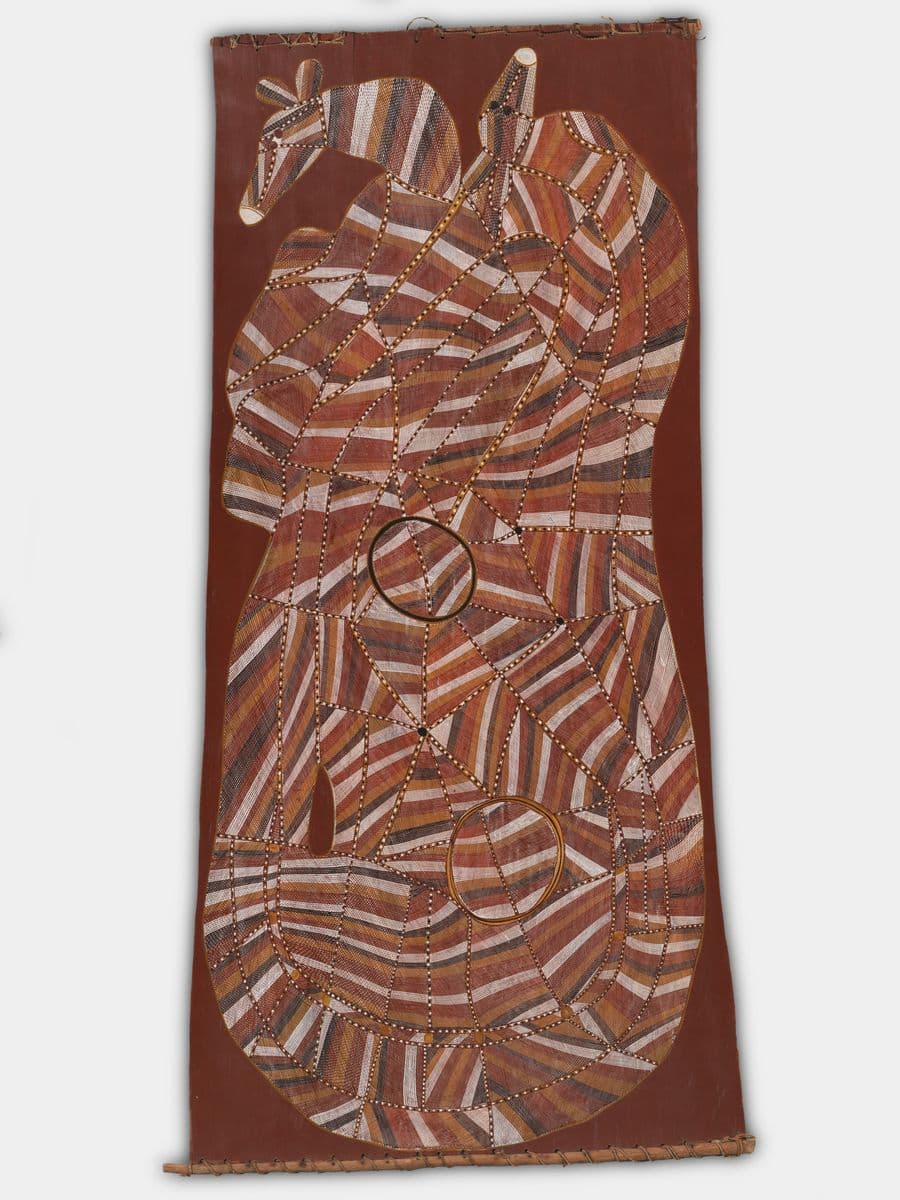

John Mawurndjul AM, Kuninjku (Eastern Kunwinjku) people, Rainbow Serpent's antilopine kangaroo, 1991, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1991 © John Mawurndjul/Copyright Agency

JOHN MAWURNDJUL

Kuninjku (Eastern Kunwinjku) people, born 1952

Rainbow Serpent’s antilopine kangaroo, 1991

John Mawurndjul’s rarrk paintings are masterful. I have long found them enthralling and I am in awe of the precision and clarity of line he achieves. Works such as Rainbow Serpent’s antilopine kangaroo can also be seen as accomplished drawings, the brush becoming a stylus in the hands of an expert draughtsman. What is especially hypnotic about Mawurndjul’s bark paintings is the rhythm and metre of the imagery, its symphony and song.

Even though it is a stretched comparison across time and cultures, this piece reminds me of certain paintings by Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky. Their work owed a great deal to the lexicon of music, and their endeavour to paint intangible worlds is present also in Mawurndjul’s assured telling of a supernatural Rainbow Serpent creation story.

While the ochre‑derived tones in bark paintings are generally restrained, this limited palette sharpens our focus on what is present: the sweeping forms in the composition. As if to balance the painstaking detail in this work, our eyes are invited on a grand journey through Country and legend. Pushing against the boundaries of the bark, the bodies of kangaroo and serpent are entwined without separation, forever meandering between this world and the next.

Sidney Nolan, Boy and the moon, c.1939-40, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1976 © Sidney Nolan Trust

SIDNEY NOLAN

1917–1992

Boy and the moon, c. 1939–40

Sidney Nolan’s Boy and the moon captured my attention the moment I saw it. The simplicity of the composition and palette evoke a potent symbolism. Based in a semblance of ‘realness’ (the sight of Nolan’s friend’s head silhouetted against a full moon), the work proposes possibilities of abstraction in painting that were radical at the time. I enjoy its artistic ambiguity, the image alternating between a modernist approach to figurative representation and a personal or subjective response to something the artist has seen and experienced.

Less obvious than those art‑historical narratives are connections I have made between the work and the story place of Wiinggina/Lake Eacham in the Atherton Tablelands from where my Aboriginal family comes. The golden silhouette of Nolan’s friend is strikingly similar to the volcanic crater lake seen in aerial photographs mapping the area. Both forms are reminiscent of a human head or brain with a spinal stem, which in the case of Wiinggina seems a significant and magical coincidence given it is a Dreaming site. Boy and the moon is a canvas for our imagination, its sparse composition allowing viewers to gaze, to dream and to wonder.

Margaret Preston, Shoalhaven Gorge, N.S.W., 1953, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1983 © Margaret Rose Preston Estate/Copyright Agency

MARGARET PRESTON

1875–1963

Shoalhaven Gorge, N.S.W., 1953

I view Margaret Preston as a remarkable artist. Shoalhaven Gorge, N.S.W. is a lyrical piece, its palette characteristic of many works from this period of her career. It is a landscape scene I find captivating; her use of earthy tones and bold lines suggests a topography that is both forested bushland and rocky outcrop. This work also reflects Preston’s interest in Aboriginal art and its interpretation; the artist was outspoken in her desire to create a national art combining First Nations and Western styles.

In her essay on the work, Kirsty Grant suggests that the imagery ‘uses all of the elements Preston identified in Indigenous art’.1 That is, she brought together differing cultural perspectives in the work as a way of unifying them. In retrospect, her artistic foray was an indelicate co‑option, reflecting a prevailing absence of sensitivity and consideration for Aboriginal culture and people. The issues Preston’s work raises are still relevant in many fields of life and art, reflecting ongoing concerns around balances of power, determination and understanding of difference.

Anselm Kiefer, Abendland [Twilight of the West], 1989, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1989

ANSELM KIEFER

Germany, born 1945

Abendland (Twilight of the West), 1989

Soon after arriving in Kamberri / Canberra to begin my studies at the School of Art in 1992, I visited the National Gallery of Australia on a hot February day. It was quiet in the Gallery. One of the first paintings I encountered was Anselm Kiefer’s Abendland (Twilight of the West), which had been recently acquired. I recall standing in front of the work as being a visceral and profoundly moving experience. It held my gaze and heart in ways I couldn’t fully understand at the time, revealing the magnetism and compelling power a work of art could possess.

An element of the piece that captivated me was the circular maintenance hatch imprinted in the lead. The power of this symbolic sun recalled in my mind the white‑hot discs that swirled in JMW Turner’s turbulent, or sunset, skies — a quietly violent yet enthralling part of the picture. In Kiefer’s work, it is more unsettling, adding an air of foreboding as the ochre disc floats ominously above diverging rail tracks, suggesting haunting echoes of the Holocaust. The painting contained all that I felt at the time a young artist should aspire to: a powerful composition, intellect, emotion and imagination in colour, material and form that touched both soul and spirit.

This story was first published in The Annual 2022.

Danie Mellor features in Artists Artists, a five-part podcast series connecting audiences with works of art from the national collection hosted by Jennifer Higgie.

Subscribe via your favourite podcast app or listen online.

- Kirsty Grant, 'Margaret Preston's Shoalhaven Gorge, New South Wales', NGV Art Journal, no 48, 2014, accessed 30 July 2022, https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/essay/margaret-prestons-shoalhaven-gorge-new-south-wales.