Life is one long decay, no?

JAKLYN BABINGTON takes an in-depth look at the practice of URS FISCHER and his candle sculpture Francesco.

The practice of Swiss artist Urs Fischer is a unique expression in an era of image saturation and, in its diversity, resists easy classification. His sculptures engage with the ongoing problematics of the plastic arts — scale, perspective, surface — yet it is his provocative presentation of unusual materials that has carried his work to a global audience. The use of wax is now iconic of his practice, and the material both forms the work and enables its cyclic ruination, as it can be recast again and again. Through an exhibited burning of his wax sculptures, Fischer presents this transformation as haunting alchemy, a staged disintegration of the body as poignant metaphor.

'The use of wax is now iconic of his practice, and the material both forms the work and enables its cyclic ruination, as it can be recast again and again.’

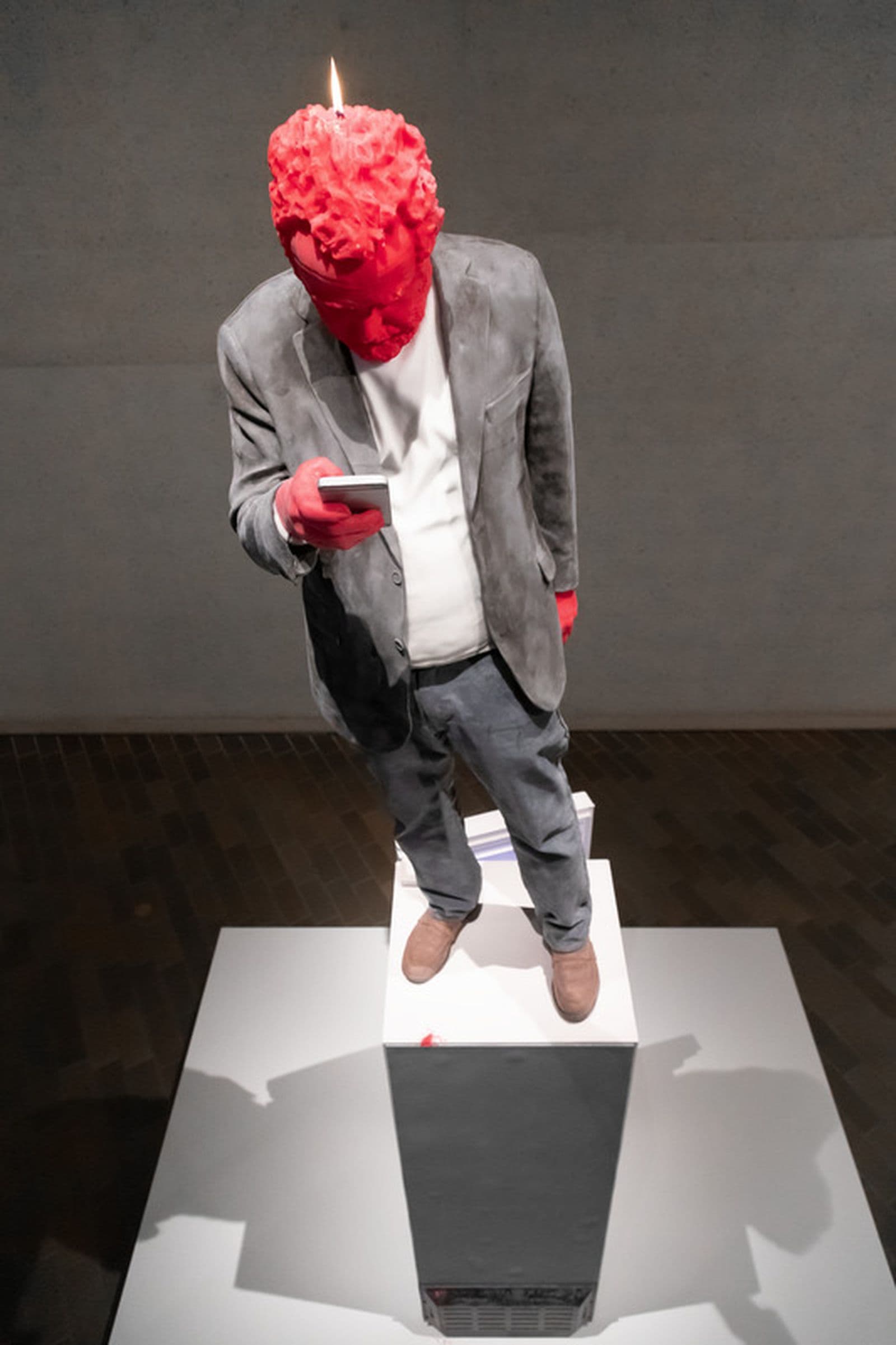

His earliest wax figures of 2001 were anonymous and crudely cut female forms, but he has developed his recent wax figures into refined portraits of art world luminaries. Francesco 2017, acquired by the National Gallery in 2019 and now into its second burning cycle, is a portrait of the lauded Italian art curator Francesco Bonami and represents one of Fischer’s highly celebrated candle works. It joins the lineage of Untitled (Rudolf Stingel) 2011, Standing Julian 2015 and Dasha 2018. Most memorable among Fischer’s candle works was his 2011 Venice Biennale presentation of Untitled 2011, depicting Giambologna’s sixteenth-century Rape of the Sabine women.

Giambologna is known to have created figurative studies in wax, and two examples are preserved in the Victoria and Albert Museum collection in London. In idiosyncratic antithesis to the Renaissance sculptors, however, Fischer prioritises expiration in his work and, in doing so, poses challenges to art-historical and art-market expectations for permanence.

Installation view of Urs Fischer, Francesco 2017, purchased 2018 © Urs Fischer. Courtesy the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London

In a humorous take on sculpture’s traditional presentation of an ‘important man standing on a plinth’, Francesco depicts the male figure casually hunched and standing on top of an open, stocked refrigerator. Looking down at his smartphone, perhaps checking his email or text messages, Bonami is captured in a pose emblematic of our contemporary era. On first glance, the work appears an incongruous selection of imagery — figure with phone, refrigerator, fruit and vegetables — yet it stands as sly reference to the star curator’s public statements on the presumed demise of the curator in the twenty-first century.

‘Fischer prioritises expiration in his work and, in doing so, poses challenges to art-historical and art-market expectations for permanence.’

In a 2016 Artnet interview, Bonami suggested that curators (himself included) had become ‘irrelevant’ to today’s art market: ‘We are like “painting”,’ he says, ‘always on the verge to be declared dead but still quite alive’. In this light, we can read Fischer’s combination of imagery as an amusing enactment of Bonami’s statement and professional predicament: the refrigerator alludes to the preservation of life, yet the burning of the work is a reminder of our mortality and the inevitable death of all things.

Urs Fischer, ‘Francesco’, 2017, purchased 2018, © Urs Fischer, courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London

‘the refrigerator alludes to the preservation of life, yet the burning of the work is a reminder of our mortality and the inevitable death of all things.’

While specific, the subject of Fischer’s candle work holds less significance than its material concerns. As a sculpture set in a continuous cycle of melting and recasting, Francesco is ignited as a figurative portrait and extinguished as anti-form abstraction. Over several months, the constant heat of candle flame reduces the sculpture to a pile of debris. Francesco’s face and hands melt, dripping long stalactites of red wax before collapsing completely and falling to the ground. This exquisite metamorphosis from individual to indefinite and representation to reality is a gradual process that evokes the grains of sand trickling through an hourglass and stands as an allusion to life flickering for a mere moment in history.

Installation view of Urs Fischer Francesco 2017, purchased 2018 © Urs Fischer. Courtesy the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London

‘Life is one long decay, no? There’s a lot of beauty in it. Like the patina in an old city.’

Fischer selects wax as an energised medium and, under a flame, the sculpture becomes animated. But with life also comes death, and it is as a contemporary memento mori that Fischer’s sculpture reverberates. While the life cycle of the sculpture begins anew with each recasting, a gnawing loss pervades. We are left pondering the rapid continuum of the next generation of artists, curators and works of art that step up to take their fleeting moment on the art world’s centre stage.

Fischer was born in Zurich, Switzerland, in 1973 and trained as a photographer at the Schule für Gestaltung. Since 1996, he has held solo and group exhibitions throughout the northern hemisphere. His first large-scale European solo exhibition was Kir Royal at the Kunsthaus Zürich in 2004, while his first in America was Urs Fischer: Marguerite de Ponty at the New Museum in New York in 2009. Fischer has since enjoyed a meteoric rise and is now feted as one of the art world’s most exciting contemporary practitioners.

This feature was first published in Artonview, no 97, autumn 2019.