Nan Goldin’s lens on relationships

The ballad of sexual dependency

Nan Goldin, Nan on Brian's lap, Nan's birthday, New York City, 1981 from the series The ballad of sexual dependency, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2021 in celebration of the National Gallery of Australia's 40th anniversary, 2022 © Nan Goldin

Curator of Photography ANNE O'HEHIR discusses NAN GOLDIN'S The ballad of sexual dependency (1986) – the defining work of Goldin’s life.

In the 1990s, the American relationships counsellor John Gray published a book debunking the notion that men and women share the same expectations and communication strategies in relationships. A pop psychology smash hit, Men are from Mars, Women are from Venus (1992) spent 121 weeks on the best seller list, becoming the decade’s highest ranked work of non-fiction, with 6.9 million copies sold.

The territory of Gray’s best seller had however already been well and truly mined by the American photographer Nan Goldin, whose work since the early 1970s had unpicked the mythologies of romance and demonstrated her belief that 'men and women are irrevocably strangers to each other'.1 Across a sequence of 126 images, Goldin’s suite of Cibachrome photographs, The ballad of sexual dependency (1986), also published by Aperture as a book, distilled many of the concerns her practice had addressed over the previous decade and half. A self-portrait of Goldin and her boyfriend Brian begins the sequence: Nan sits on Brian’s lap, her arms around his neck, smiling for the camera; an unsmiling Brian looks into the lens with suspicion and a certain indifference. The portrait of Nan and Brian is immediately followed by two other images of couples who seem to be 'irrevocably strangers': a photograph of wax models of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor at New York’s Coney Island amusement park, then a portrait of Goldin’s tight-lipped parents, not touching, seemingly lost in their own worlds. Together, these images support Goldin’s lament in the book’s preface, that men and women are 'irreconcilably unsuited, almost as if they were from different planets.'2

Nan Goldin, The Duke and Duchess of Windsor, Coney Island Wax Museum, 1981 from the series The ballad of sexual dependency, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2021 in celebration of the National Gallery of Australia's 40th anniversary, 2022 © Nan Goldin

Nan Goldin, The Parents at a French Restaurant, Cambridge, Mass., 1985 from the series The ballad of sexual dependency, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2021 in celebration of the National Gallery of Australia's 40th anniversary, 2022 © Nan Goldin

The ballad began life as a slide show presented in the apartments of Goldin’s friends and the clubs of Manhattan where she lived and worked during the late 1970s and 1980s. The audience for these events were generally the people in the images – the post-punk, creative, queer scene that comprised Nan’s community, her chosen family. As well as being an expedient way to show her photographs (it was incredibly expensive at the time to make colour prints, and Goldin was unable at times to access a darkroom), the slide show version of The ballad was also quietly iconoclastic: it subverted a domestic ritual popular in the United States during the 1950s and 1960s, which usually involved families and neighbours sitting around a slide projector while fathers told stories of travels as they flipped through the slides.

Goldin’s ever-changing slide shows were much anticipated, promoted by word-of-mouth and then with handmade bills posted around New York’s Lower East Side. The ballad had an arresting theatricality, performed in a darkened space accompanied by a soundtrack of popular and classical music. Regardless of the venue or the crowd, the narrative arc was consistent: young people negotiating new ways of forging intimate relationships, escaping middle-class familial and social restrictions and expectations, getting high, hanging out, partying, playing boardgames, falling in and out of love, having sex, drifting off to West Berlin or Mexico. Goldin continued to play with the image sequence over many years. The flexibility of the slide show format gave her the opportunity while she was living the life she was documenting – making ends meet, living a life by night – to rethink and refine the work.

The ballad occupies a place between film and photography, with sequences and pairs of images sparking off each other, and the slide show format giving the project fluidity and open-endedness. The influence of cinema is everywhere, not just in the way that the narrative unfolds, but also in the style of the images themselves, and the fact they were projected on a wall in a darkened space, as in a movie theatre. Much of Goldin’s early visual education happened in cinemas, often watching double features with her friends David Armstrong and Suzanne Fletcher while they were students, igniting a love of legendary directors, many of them European, including Michelangelo Antonioni, Jacques Rivette, Henri-Georges Clouzot, François Truffaut, Alain Robbe-Grillet, Douglas Sirk, John Cassavetes, and Michael Roemer, as well as the experimental films of John Waters, Andy Warhol and Jack Smith. There were also the influential independent women filmmakers that she knew, and at times worked with, Bette Gordon and especially Vivienne Dick, without whom Goldin later reflected The ballad would not have been made, inspired as it is by Dick’s commitment to fragmentation and her ability to be non-judgmental even when dealing with difficult subject matter.3

The work’s title finds its inspiration in the song, Die Ballade von der sexuellen Hörigkeit from Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht's 1928 opera Die Dreigroschenoper (The threepenny opera). Arising out of the interwar European demimonde world so beloved of Goldin and her cohort, Brecht’s lyrics make an argument for an open and frank depiction of human sexuality, one uninflected by hypocrisy, prejudice or sentimentality. In turn, Goldin employed the documentary mode, evoking its long-understood attribute of objective truth, its role as witness. In her hands it came from an altogether passionate and engaged place – an intimate, unredacted, non-judgmental and empathic portrayal of lovers and friends, and of the ways that desire infuses all our relationships. She refers to The ballad as her ‘public diary’ and, by way of negotiating the complex politics that accompanies the act of taking photographs of others, has stated that her images 'come out of relationships, not observation',4 dismissing as essentially irrelevant any notion that photography should be impartial or detached.

Goldin’s position is that there is no distinction between her life and her photography:5

'People in the pictures say my camera is as much a part of being with me as any other aspect of knowing me. It’s as if my hand were a camera. If it were possible, I’d want no mechanism between me and the moment of photographing. The camera is as much a part of my everyday life as talking or eating or sex. The instant of photographing, instead of creating distance, is a moment of clarity and emotional connection for me.'

She reminds us throughout The ballad that she is part of this community, never outside of it. Rarely do we see any evidence of the camera itself, even when Goldin is shooting in front of a mirror: the camera seems to have merged with Goldin’s body and her desire. This is a form of embodied looking, where vision and the experience of desire becomes haptic. It is altogether fitting that the original title of The ballad was If my body wakes up.6 This relationship to the body carries through to the experience of the Cibachrome prints, currently on display at the National Gallery. Cibachrome is a colour printing process that was popular during the 1980s and 1990s, resulting in prints that have a metallic quality and appear to have real weight, with sumptuous, highly saturated colour that is in a way similar to the experience of projected slides, as both shimmer with light. At times Goldin gets in close to her subject, as if we, as viewers, could reach into the image and caress the flesh that Goldin lays bare for us. In fact, each of the iterations of the project – the slide show, the book, and the Cibachrome prints – retain a specific, material relationship to the subject of the work: the darkened shared space of the slide show; the intimate, personal experience of the book; the luscious, exuberant beauty of the Cibachrome photographs.

Whereas Men are from Mars, Women are from Venus sought to help straight men and women find a way to better understand each other, Goldin’s project had a decidedly disruptive agenda: it set out to radically rethink the ways that lovers and friends relate to each other. While the photograph of Nan on Brian’s lap formally opens the sequence of images that comprises The ballad, an image that precedes the title page for the book is of another couple, a portrait of Goldin’s good friend, the transgender artist Greer Lankton, lying on a bed next to her ex-boyfriend Robert Vitale, both looking away from each other, seemingly estranged, in an image that still resonates with pathos and melancholia. Lankton is 'looking inward,' Goldin later wrote of this image, 'full of longing, thwarted desire and her essential loneliness.'7 The figures of Greer and Robert, who was a gay man, do not figure in the landscape of relationships elaborated by Men are from Mars, Women are from Venus. Nor, for that matter, does Nan Goldin herself, who has always asserted her own queerness; nor any of the many other queer subjects who recur throughout The ballad. The ballad stakes out a space for queerness from the very start: like Goldin’s practice more broadly, The ballad is saturated with it.

Nan Goldin, Greer and Robert on the bed, New York City, 1982 from the series The ballad of sexual dependency, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2021 in celebration of the National Gallery of Australia's 40th anniversary, 2022 © Nan Goldin

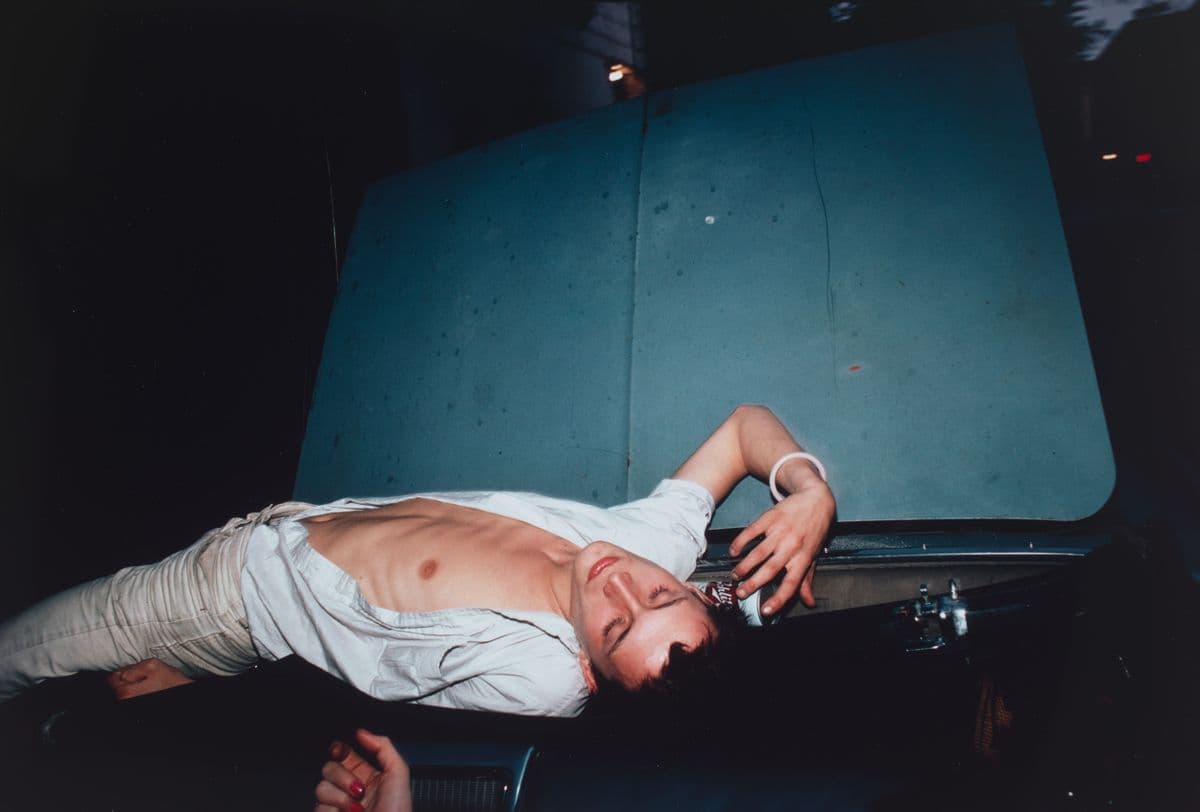

Images of couples recur throughout: sometimes romantically and sexually linked, but just as importantly linked through complex webs of friendships and intimacy. The project continues the aspirations of the women’s and gay liberation movements of the 1960s and 1970s that sought to find new ways of forming social and intimate relationships. Goldin’s images acknowledge this history in many ways, including iconographically: her photograph French Chris on the convertible, New York City 1979 sends us straight back to Henry Wallis’s decidedly homoerotic Death of Chatterton from 1856.

Nan Goldin, French Chris on the convertible, New York City, 1979 from the series The ballad of sexual dependency, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2021 in celebration of the National Gallery of Australia's 40th anniversary, 2022 © Nan Goldin

Everywhere too there are feminist politics at play here. In her photographs, Goldin disrupts what the film critic Laura Mulvey famously called in 1975 ‘the male gaze’. This gendered way of looking, developed through our experience of cinema and photographic imagery, presupposes that the maker and ultimate consumer of imagery is male, his desire often located in the experience of a film’s male protagonist, with women positioned as passive objects of desire – never in control of imagery or the pleasure that often comes with acts of looking.8 'It's so rare to see a woman's sexuality, real female sexuality,' Goldin has noted9, and a central tenet of her practice is to portray that which is usually kept hidden. In more than a third of the images, we see people in their most intimate places; in bathrooms, in the shower or on the toilet, in bedrooms and so often on the bed itself – sprawling, having sex, arguing, hanging out.

Goldin is acutely aware that the gaze in cinema and photography is often gendered, and that the gaze constructs ideals of feminine beauty. She grew up spending hours watching films starring Marilyn Monroe, Marlene Dietrich, Bette Davis and Joan Crawford, 'all of the Hollywood goddesses we were obsessed with', at the same time absorbing Hollywood cinema’s ways of being and looking: 'the movies I love are deeply imprinted on my brain and my world view'.10

One moment Goldin is behind the camera as creator, and the next she is also in front of it as subject. She freely flips between active and passive positions: in images of herself, titles are at times given as ‘self-portrait’ and at others she uses the more objectifying ‘Nan’. In complicating the ways that women are positioned as subjects of the gaze, Goldin also acknowledges the pleasure that comes with being seen. The ballad includes a sequence of four photographs showing women (including Goldin herself) looking into mirrors, creating themselves as objects of desire and consumption. Goldin is acutely aware of women’s complicity in the game of attraction and seduction, reminding me of the Canadian author Margaret Atwood’s observation that 'you are a woman with a man inside watching a woman. You are your own voyeur.'11 Goldin also acknowledges in these pictures of women preparing themselves in the mirror how, through this act of looking, women (and men!) model themselves – and how in private we compose, practice and perform our public selves. In The ballad, the mirror becomes a surrogate for the ways that we present ourselves in front of the camera.

Nan Goldin, Self-portrait in blue bathroom, London, 1980 from the series The ballad of sexual dependency, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2021 in celebration of the National Gallery of Australia's 40th anniversary, 2022 © Nan Goldin

Nan Goldin, Suzanne with Mona Lisa, Mexico City, 1981, 1981, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2021 in celebration of the National Gallery of Australia's 40th anniversary, 2022 © Nan Goldin

Nan Goldin, Sandra in the mirror, New York City, 1985 from the series The ballad of sexual dependency, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2021 in celebration of the National Gallery of Australia's 40th anniversary, 2022 © Nan Goldin

Nan Goldin, Suzanne in the green bathroom, Pergamon Museum, East Berlin, 1984, 1984, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2021 in celebration of the National Gallery of Australia's 40th anniversary, 2022 © Nan Goldin

Nan Goldin, Käthe in the tub, West Berlin, 1984 from the series The ballad of sexual dependency, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2021 in celebration of the National Gallery of Australia's 40th anniversary, 2022 © Nan Goldin

This is a body of work that comes unapologetically from a female perspective. It is the women in the images who open themselves up to Goldin in all their upset and their hurt. How raw and heart-breaking is the image of Suzanne in tears, one of many images of women seen in moments of vulnerability and neediness.

Nan Goldin, Suzanne crying, New York City, 1985, 1985, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2021 in celebration of the National Gallery of Australia's 40th anniversary, 2022 © Nan Goldin

The community that Goldin shows us in such vivid, evocative images, full of desire, barely able to contain the shimmering life and intense emotions we see depicted, was decimated through forces out of anyone’s control. This era witnessed the dramatic transformation of New York through gentrification, and waves of deaths from addiction, especially heroin, and from the devastating impact of HIV/AIDS, which by 1986 was responsible for 2,710 deaths in New York alone. We bring to The ballad the knowledge that so many of the young people depicted in it never had the opportunity to grow old. Goldin’s close friend, the actor and writer Cookie Mueller, is seen in all her vibrant, laughing splendour in The ballad, hanging out at Tin Pan Alley or with her son Max, marrying the artist Vittorio Scarpati. She would be dead three years after the book and the portfolio were made, as would Vittorio.

Nan Goldin, Cookie and Vittorio's wedding, New York City, 1986, 1986, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2021 in celebration of the National Gallery of Australia's 40th anniversary, 2022 © Nan Goldin

Nan Goldin, Cookie with Max in the hammock, Provincetown, Mass,. 1977, 1977, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2021 in celebration of the National Gallery of Australia's 40th anniversary, 2022 © Nan Goldin

This was a vulnerable group of people enduring a hostile and insufficient response from the Reagan administration and fear and rejection from mainstream society. Goldin, however, chose to show this community not as one defined one-dimensionally by addiction, illness and death. It is a project that examines the nature of desire and what happens when love turns into jealousy and obsession between men and women – Goldin’s unflinching self portrait, taken a month after Brian beat her so badly that she almost lost an eye, lies at the heart of the project. It is also ultimately about an expanded understanding of intimacy that embraces community and friendship.

'The need to be loved by friends has been as important to me than any lover I’ve had all my life. This is part of the reasons that my lovers don’t stay because they are jealous of how much I care about my friends.' [12]

Nan Goldin, Nan after being battered, 1984 from the series The ballad of sexual dependency, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2021 in celebration of the National Gallery of Australia's 40th anniversary, 2022 © Nan Goldin

Already by 2003, the novelist and cultural critic Lynne Tillman was asserting that The ballad had 'forged a genre, with photography as influential as any in the last twenty years'13 and its legendary status has only grown since that time. Goldin herself, who has gone on to a very successful career, acknowledges it to be the defining work of her life, the way she found to make her mark.14 The ballad is now considered a cornerstone of contemporary photographic history. Highly significant contemporary artists such as Wolfgang Tillmans, Ryan McGinley and Corinne Day freely acknowledge their debt to Goldin; her work has also been very influential in Australia, where the style and long-form, intimate nature of her work has informed the practices of Paul Knight and Lyndal Walker amongst many others. As well as drawing heavily on the history of cinema, the style and intimate nature of Goldin’s work has also influenced many of the world’s leading directors, including Wong Kar Wai, Harmony Korine and Alejandro Landes. As widely lauded as it has become, however, it holds a special, particular place as a form of love letter from Goldin to those she terms ‘her tribe’; a paean for those who survived and a testament to those who didn’t. It remains a remarkable gift to her community. Many of the images in The ballad remain secretive, full of backstories known only to the people in them and their close circle.

By the mid-1980s Goldin was already working with an acute awareness, as she surveyed the slides littering her light table from the last decade and a half, that this was a world that was irrevocably lost, evoking one of the most compelling and powerful compulsions in documentary photography. There is a melancholy that infuses The ballad of sexual dependency, especially as it draws to its desolating conclusion as we turn the last pages of the book, or reach the end of the photographic sequence on the gallery wall, as we encounter suddenly bleak scenes of empty beds, a graveyard, and skeletons.

Nan Goldin's The ballad of sexual dependency is on display from 8 July 2023 to 28 January 2024.

VIEWER ADVICE

Please be advised that works of art in this exhibition depict explicit nudity, sexual acts, drug use, and the impacts of violence against women.

Viewer discretion is advised.

This exhibition is not suitable for children under the age of 15.

The photographs in Nan Goldin’s The ballad of sexual dependency depict the everyday lives, often in intimate detail, of people in Goldin’s immediate community during the late 1970s and early 1980s.