Reflections on a life in print: Kenneth Tyler in conversation

In September 2022, Assistant Curator David Greenhalgh visited the master printer Kenneth Tyler at his home in the countryside surrounding New York. They discussed Tyler's role in printmaking history and the projects that he undertook with artists such as Roy Lichtenstein, David Hockney, Jasper Johns and Helen Frankenthaler from the 1960s to the early 2000s. The following transcript has been edited for readability:

KENNETH TYLER: So, what's the one big question you want to ask?

DAVID GREENHALGH: Let’s start with a question from [the National Gallery's Distinguished Adjunct Curator] Jane Kinsman: What do you think made the artist Frank Stella an important figure in printmaking?

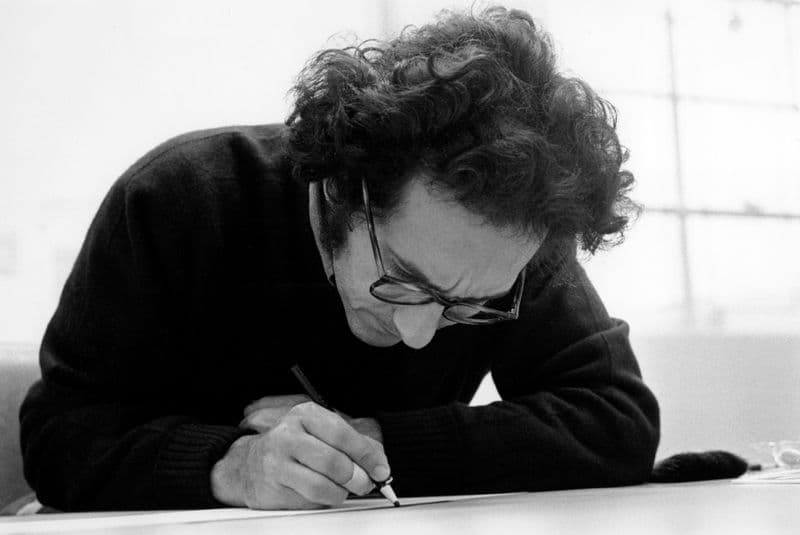

KT: Well, he was a reluctant printmaker. He was convinced he couldn't make prints and yet he did make prints. Stella is all about coming into print world completely naive and without any background for it. He didn't study it and didn't have any kind of technology to offer. He comes in there and is talked into doing the Star of Persia with a felt tip pen.

-

Frank Stella drawing at Gemini GEL, Los Angeles, 1970 (c) Malcolm Lubliner

-

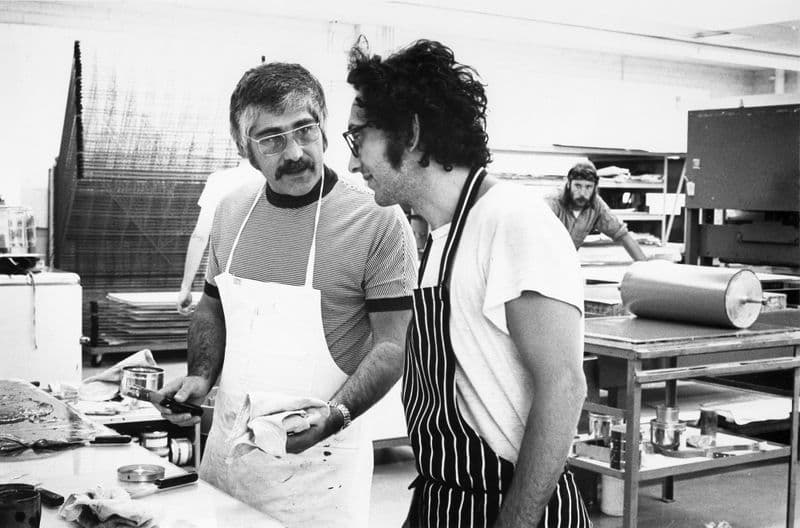

Kenneth Tyler and Frank Stella in discussion as Tyler mixes ink for Stella’s ‘Newfoundland’ series, Gemini G.E.L., Los Angeles, California, 1970 (c) Malcolm Lubliner

So, from there we go on. He's always being taught something about printmaking and he absorbs it. The wonderful part of all is his innocence in not knowing anything. In that way he becomes the perfect pupil to learn something, because he comes as a blank canvas and we get to fill him with all sorts of information. He takes it away and brings it back and it's his. When Frank says ‘you taught me everything about printmaking’ it really is a compliment. He was a good student. I think once you get hooked on making prints you rely on that activity. It becomes a very important part of your creative life. So I think that in Frank's history with me, we had a lot of good creative moments. Then all of a sudden, now, we have none. It's a very strange thing to think, ‘Frank is coming over for dinner’, but he's not coming over to work. There is no work anymore, so we're unemployed. We think about it, but we also don't know what to do with it. There are possibilities, but they're not possibilities.

All of it revolved around having a workshop. The workshop was the catalyst for everything that happened.

Ken Tyler operating his newly designed hydraulic lithography press at Gemini Graphic Editions Limited, Los Angeles, California 1968. The flat and consistent areas of colour that this press created became a signature for the workshop at the time. Unknown photographer

It became a destination. We developed the paper mill and that became more and more the place to work, for a lot of artists. Frank was no exception to that, and you can see us at John Koller’s [papermill] making those paper pieces in a primitive way,

DG: Is that at HMP? At Hand Made Paper papermill in Connecticut?

KT: Yeah. We all grew up with this papermill. As it grew in size, so did the complications and so did the artwork. A lot of it evolves around my hydraulic press. Every artist came in and used that press and used that room, did something different.

Ellsworth Kelly spoons pulp through a plastic image mould for "Blue/Green/Yellow/Orange/Red" at HMP Papermill, Woodstock, Connecticut, 1976 Photograph by Betty Fiske

DG: I think about how Frank Stella's later prints use lots of print matrices all fitting together like a jigsaw. Something like Juam from 1997, which is gigantic, and uses all these textured metals individually inked up. It feels as though it evolved from these simple origins into something beyond printmaking itself.

KT: We used to call that ‘one shot printing’. That was a term that Frank coined. Because it was a big mystery to put all those tiny pieces in the press and to lift off the felts and the paper and we would all just go wow.

Printer Anthony Kirk inks a section of the printing element jigsaw used for Frank Stella's 'Juam' from the 'Imaginary places' series at Tyler Graphics Ltd. Mount Kisco, New York State, March, 1997 Photo by Marabeth Cohen-Tyler

DG: Frank Stella liked to gamble?

KT: He was a gambling man. When you've had a long history together you have a lot of trust and that trust goes a long way. It allows oneself to be free in the creative act and not to be too conscious of the other person that you're collaborating with. It makes the collaboration that much better and richer in every way. It’s a history you can't repeat. There’s no sense in trying. That is true of every other artist collaborator. Each one works differently, but they're all the same in many ways. The artist starts to trust the situation and open up to doing something and you find out something really nice that you like doing. Because I was always open to doing it again, we did some good things together.

David Hockney in the Gemini GEL studio surrounded by proofs for his 'Weather' series, Los Angeles, 1973. Photo by Daniel B. Freeman

DG: In your mind, what made David Hockney an important figure in printmaking?

KT: He was a draughtsman. He came in and was able to draw on the spot. He was an artist that worked with his hands. He liked materials, moving things around and making things.

DG: I guess that it was important for you to always be thinking of the hook, that little idea or new technology to get Hockney interested?

KT: Remember that the workshop is magical. It's a magical place. It's inventive, surreal. It's ever changing and the environment is always different, depending on who's been there, and who has left. Sometimes, I would change the stage set and make it look like it's brand new, and other times I wouldn’t bother.

I gave up a long time ago trying to make it a nice clean environment for the artist to come in and work and to not have the influence of the previous person being there.

DG: So the remnants of the previous project would be hanging around?

KT: Yes I gave up the stage set business and I think the artists looked forward to coming in and seeing what the other people were doing. It became a building block situation: A person would come in, making a contribution that was being recorded, seen and saved. It made it a very special place.

DG: I can sense people coming in one after the other. Artist A has left something behind and Artist B picks up a little element of that carries it forward for their project and it keeps going. What about the incident you mentioned yesterday: Of James Rosenquist failing in his own studio, trying to make paper pulp artworks with a stucco pattern pistol, and this bringing him to back to you?

KT: Well, he didn't have a print studio, so he didn't fail. He tried to take some of the specialist knowledge from our workshop, such as the spray gun, back to his studio in Florida and of course couldn't make it work because he didn't have the presses and stuff to do it right. It was in his head that he could take this spray gun and get some paper pulp and begin to play with it. But it doesn't work that way. It's just too much. I marvel at that because he was honest enough to tell me about it. He was laughing at himself. This simple room called the paper mill that we had was not so simple: When you look at it. There was the making of it, the drawing of it, it was all sorts of things. I think it was perhaps the first time that Jim ever looked at collaboration in a very serious way. I think he's had collaboration in his past, but he didn't really analyse it. All of a sudden, in trying to take it away to his studio, and not realising that he needed the instruments and the people to make it happen. That was quite gratifying for me to hear. It gave new meaning to our experiments.

James Rosenquist operates a stucco spray gun for his print 'Time dust', Tyler Graphics, Mount Kisco, 1990. Marabeth Cohen-Tyler

DG: Where did your philosophy of ‘discarding the rulebook’ come from?

KT: I was a rulebreaker. Because I was so energetic at the time, I was making my own rules. It's almost humorous because it was a badge of honour to have printmaking rules in the printmaking world.

DG: The way that [curator] Pat Gilmour frames it is that you began by looking at how Pablo Picasso was playing with the rules while working with print, and you were saying, I could do that here in the United States. Is that correct?

KT: Well, yes, kind of, I did have a pretty good knowledge of Picasso's work. I liked the idea of his collaborations. He was more than able to collaborate, and very gifted at working with people. He was my model. I always thought Picasso was a great educator. His work was very informative for me. I liked everything he did.

DG: Tell me about the moment that you learnt that Picasso had become aware of your workshop.

KT: He said to my friend Eva af Burén, my friend in Sweden. They were good friends and

she told me that Picasso said ‘tell Mr. Tyler to come over with his press’ as if suddenly I could just put it in a suitcase.

It was such a sweet thought. He had seen [Rauschenberg’s] Booster the big print I made in 1967. I was trying to seduce him with scale. ‘Six feet. Come on, you’d want to do that wouldn’t you?’

DG: Were you directly sending him letters and photos?

KT: No just through Eva, who was the messenger, the translator. I didn't speak French and this was going to be a problem. Even if I got together with him, his English was not that good. A nice thought, working with Picasso, but that was it.

DG: It's fun to imagine what you two would have sat down to make.

KT: It’s two different worlds.

DG: Picasso's an innovator, but I feel like you had already come around a curve, and perhaps your world would have been too transgressive for even Picasso to be working within.

KT: I can't imagine. I don't know what went through my head, to think that I was even capable of being a collaborator with him. You idolise somebody like Picasso.

DG: Maybe there would have been a six-foot Picasso print. You have this long collaborative career with Roy Lichtenstein. What was Roy’s time in the studio like?

KT: Roy was a worker, seven days a week, constantly making things, while David Hockney could be lazy. A lot of those last woodcuts we did Roy was carving them himself with a rotary tool. He loved activity.

DG: The Nudes series was the last you produced with Roy, working with Rubylith stencils…

KT: It was just dramatic as hell to see this gigantic nude in the Rubylith red stencil. There are great photographs of [his wife] Dorothy sitting in the barber’s chair reading the newspaper, and Roy over at the table carving the woodblock, while I bring something into the studio. Those are great photographs in the archive.

DG: Actually, there’s a really intriguing photo in your archive, and it appears to be at a party in the 1960s or 70s. I think it may have been 1969, but it doesn’t have a date on it. It has Roy Lichtenstein and [gallerist] Irving Blum sitting on a couch, talking, and Blum has a Campbell’s soup can in his hand, and it looks like he’s talking into it, like it’s a microphone. Do you remember what’s happening there?

Gallerist Irving Blum with a Campbell's soup can and artist Roy Lichtenstein, Los Angeles. unknown date. (c) Malcolm Lubliner

KT: That photo I had in my office at Gemini GEL. Blum had just put on the [Andy Warhol] Campbell’s Soup exhibition at his gallery and that was the announcement. Irving was happy to have it.

DG: I was wondering if that Warhol connection was intentional!

KT: Oh yes he had the show up with all the soup cans. He also had the Brillo boxes.

DG: Speaking of boxes, Gemini GEL produced the Judd multiple in your collection. How was it working with Donald Judd?

KT: Not my favourite artist. But he was very important to the New York art scene.

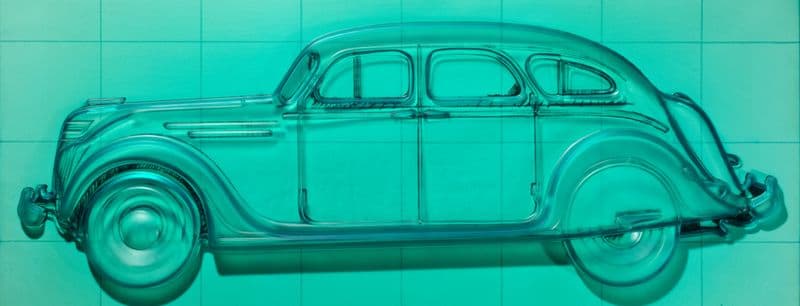

DG: Do you have a favourite multiple that you produced? Something like the iridescent John Chamberlain Le molé? Or the Claes Oldenburg multiples?

-

Claes Oldenburg, Profile Airflow 1969. Molded coloured polyurethane relief over 2 colour lithograph. Purchased 1973.

-

John Chamberlain, Le molé 1971. cast polyester resin with iridescent coating. Purchased 1973.

KT: The Claes Oldenburg Profile Airflow is a magnificent piece. The Jasper Johns Lead Reliefs and the Oldenburgs are my favourites. Those were the ones that created the big splashes.

DG: What about the Ed Kienholz?

KT: The car door? Sawdy? Ed was a great friend. We used to have some great dinner parties. Both Ed Keinholz’s wife and I loved to cook and so we made these cookies and would hold lavish dinner parties. They were absolutely wonderful. Everyone who came along was in a couple. It was a moment in time where everyone was still together.

DG: Who would come along to those dinner parties?

KT: Dorothy and Roy Lichtenstein. Los Angeles was a bohemian place in those years.

DG: When did you first meet writer and critic Robert Hughes?

KT: I met him at a Japanese restaurant. I think it was Barbara Rose that put us together, as I recall. We just hit it off. When he started visiting Robert Motherwell on a regular basis in Greenwich, we became closer and closer as friends. He would come over to use my workshop to make cabinets. He really was a character. I’ll tell you a story about him. Renate [Ponsold-Motherwell] had a brand-new Volkswagen and loaned it to Robert Hughes to go to Long Island. He would tell her that he was going to Long Island, But

Robert Hughes didn’t tell her that he was going to Long Island to fish, so there were all these fish loaded in her Volkswagen creating a stink. Things like that, he was nonchalant about a lot of things.

But he was Bob Hughes. He was certainly a character. He had a talent for cooking, really an amusing fellow. He put some great dinners together at Prince Street.

DG: His writing and his storytelling really is the backbone of the National Gallery of Australia, almost everything that he wrote and spoke about appears in the collection. So I think he has a very formative influence on us.

KT: He was well educated. Part of that was self-educated, that he sought out himself. Because he seemed to have a lot of acuity in lots of areas that doesn't come across when you read about him. He was a smart guy. He had a good sense of history. And part of that was storytelling. He liked telling stories.

DG: So do I.

KT: Maybe that's Australia.

DG: Well we've got the distance from the story so we can see it unfolding with clarity. So your first meeting with [inaugural National Gallery of Australia director] James Mollison, was he pretty direct? Was he up front and said “we want to buy it all”? Or was he a bit coy?

KT: No, he did negotiate. He was pretty much assured of what he was offering and what he was going to do. I think he knew precisely what he could get away with, and he kept coming back. I had print drawers in my house and I let him in a couple of them but I didn't show him a couple. He was very anxious to know what was in those drawers: “What sort of proofs do you have hidden here Ken? Show me show me!”. We did play this cat and mouse business a little bit, which was fun. But he had a keen eye.

James Mollison could look at something and very quickly work it out. You didn’t have to sell it to him, because he was quite attuned to it.

DG: I've read over all the telegrams that were sent back and forth between the two of you and I love that Mollison says the collection that you've given to the National Gallery “will affect the future course of printmaking in the country” and then he threatens to kidnap you for a symposium.

[laughter]

KT: Yeah, it's strange. I mean NGA, being in Australia, is one of my greatest supporters, then you have to go to Sweden to find the next one. That’s because of Björn Wetterling and people like that who took a shine to me very early.

DG: I guess it came at that right moment as well. That moment where things were in upheaval and you had to strike out afresh, looking at the East Coast.

KT: Yes, it was a heady time. I made the right decision to get out of Los Angeles. That was the right thing to do. To get to the East Coast.

DG: Do you think, were it not for Motherwell suggesting a place like Bedford [Village] you would have ended up in Long Island?

KT: Happily not. Long Island always seemed dicey at best. I spent time there. I also had a little studio there that I built over the railroad tracks. I tried to develop that into a little place that I would go to and do things. I even set up a press there. But nothing happened. I couldn't work with the artists that were out there. It just wasn't on the cards.

DG: Are you talking about the Abstract expressionists?

KT: Yeah. Well, you know, de Kooning would have been ideal for me, because we got along so well together, but he wasn’t interested in really setting up a part of his life for making prints. Because he got some bad experiences, or good experiences, I guess, in San Diego, where he did all those big prints, but which he never really spoke about too much. I always wondered about that. I used to say that myself I was offering scale and he was interested in scale but we never really got together. And then everybody was in competition. So, you know, I remember he did all those transfer paper drawings and [Irwin] Hollander came over and swiped him up, took them to the studio.

DG: Maybe if the business with de Kooning did work out, you might not have had the same engagement with [gallerist Leo] Castelli's artists. For example, you might not have had Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns come through because you were caught up in this Abstract expressionist world instead.

KT: Yes, I guess it was a mix and match thing. There was not really such a thing as Abstract expressionism, there was never really such a thing as the Castelli camp, and this camp and that camp. It was all kind of running around together in bits and pieces at that stage. We were all… everybody was involved in chasing the same thing it seemed. A piece of fame.

DG: What about your work with Andy Warhol? Did you think about working with him in New York?

KT: When he wasn’t making those stupid little films, running around Los Angeles. He always played this [deadpan] attitude.

DG: He had a lot of groupies and hangers on?

KT: Oh yes. He was a made-up figure.

It wasn’t whole cloth that Andy Warhol came from, it was pieces that he collaged together.

He was a great entrepreneur. The Factory was a good example of that. He knew exactly when it was time to show collaboration in a bigger way and then he’d open up the doors and all of a sudden, the people would flock in.

DG: Did you ever visit The Factory yourself?

KT: Yeah.

DG: How is that experience?

KT: Not very gratifying.

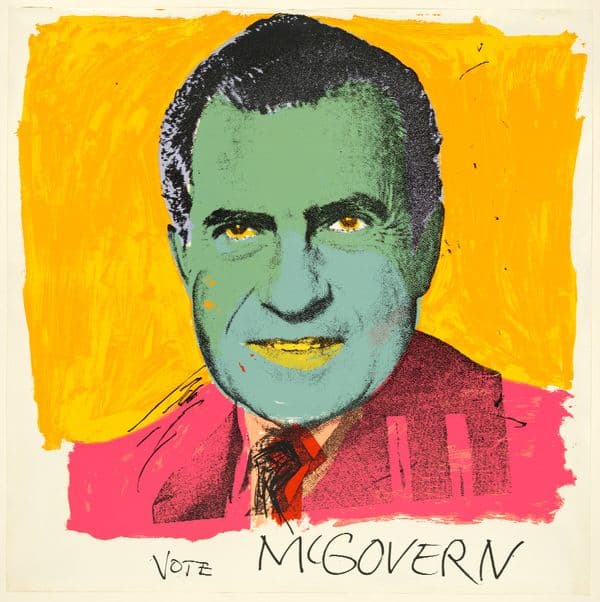

DG: Do you think Warhol was put off returning to the Gemini print studio after copping political scrutiny for his print Vote McGovern (1972) from Richard Nixon?

-

Andy Warhol, Vote McGovern, 1972, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, Purchased 1973. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./ARS. Licensed by Copyright Agency.

-

Printer Jeffrey Wasserman inspects a proof of 'Vote McGovern' by Andy Warhol, Gemini GEL, Los Angeles, 1972. Daniel Freeman.

KT: No, I don't think so. Vote McGovern was very popular. First of all, he was not involved in coming to Los Angeles and working instantly, he came to the West Coast just to do the film thing. I don't know if I pushed the right buttons with him anyway. That probably was more my failing than anything else. I like projects. To be involved in projects and I like artists that I could work with that I was involved with. Andy was all about… just grabbing little opportunities all over the place.

DG: So, none of the deep involvement and collaboration that you were interested in?

KT: He wasn’t interested in making a contribution for anybody other than himself. He could be very self-centered. That doesn't make for a good collaboration.

DG: At the same time, you've got Johns who seemed to be really deeply involved in the process of printmaking, but at the same time just reconfiguring motifs from earlier paintings.

KT: I mean Johns was copying Johns. Most of his life is about that. Even towards the present day. When we did the Lead Reliefs it just seemed like it was going to be an endless process, trying to get another image going. But Jasper is a complicated character.

Jasper Johns painting the lead relief 'Bread' with oil paint, Gemini G.E.L., Los Angeles, 1969. (c) Malcolm Lubliner

DG: Jane [Kinsman] told me that the Lead Reliefs started out as embossed paper, but the paper kept on breaking?

KT: Yes, and that’s why we went to lead. Besides, I had an entrance into Amsco, and the big hydraulic press. So, I was able to swing that right around and get into the lead, and mold making and that was fun.

DG: You told me that Jasper owned a Richard Serra lead piece at that point in time?

KT: Yes, one thrown against the wall. Richard Serra came over and threw one against the wall. It was always interesting to me how some artists I collaborated with and that relationship just stayed and sometimes grew, but sometimes they didn't at all. With Richard I didn't seem to hit it off that well. I don't know why. I suspected there was something… his agenda was different from mine in many ways. I just wanted to collaborate, and he just wanted to make things that were bigger than usual. More surprising than usual. If I was managing a foundry, then that would have a very different relationship.

DG: It feels like Johns was deeply invested in the process of printmaking and had a keen interest.

KT: Yeah, Jasper was an intellectual about it. Also pedantic. He loved doodling with the stuff. That goes back to [John] Cage and the early New York relationships that he had, and that influenced his printmaking a great deal.

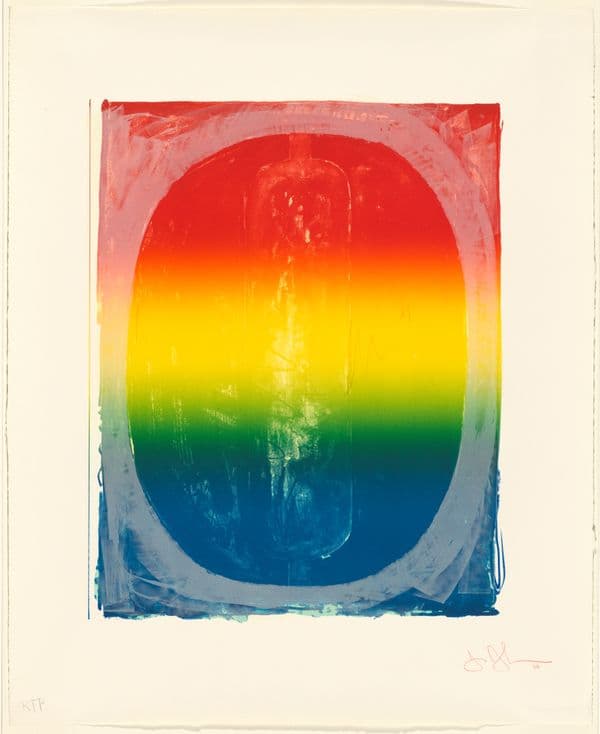

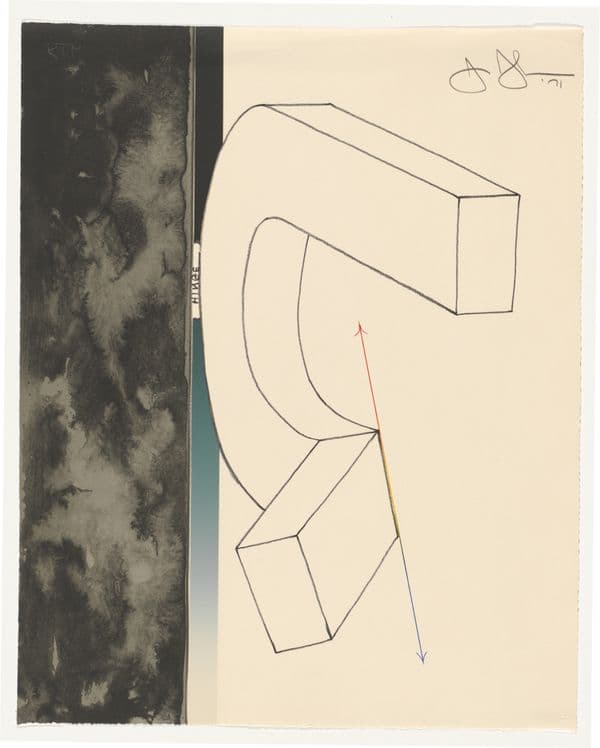

DG: One of my favourite parts of the prints that you made together is the use of the spectrum roll. He's just got the spectrum roll on a single thin little line or arrow in the print. He’s not using it as this big statement… Well he does with the Color Numerals, but later it becomes this subtle little line. I guess I’m thinking of Bent “U”. What was making the Fragments - According to what series with Johns like?

-

Jasper Johns, Gemini G.E.L., Figure 0; from Color numeral series, 1969, colour lithograph printed from one stone and two aluminium plates, 70.6 h cm, 56.4 w cm, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, Purchased 1973. © Jasper Johns. VAGA/Copyright Agency.

-

Jasper Johns, Bent “U”1971, from Fragments–according to what, color lithograph, 64 x 51.4 cm, published by Gemini Graphic Editions Limited, Los Angeles. National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1973. © Jasper Johns / Copyright Agency 2022

KT: Well, those were different to the Numerals. The Numerals were fun. The Numerals were just bigger versions of what he did it ULAE, and throughout his life: Zero to Nine.

DG: Did he talk about what they meant to him?

KT: Very little. We grunted a lot.

[laughter]

DG: There was Jasper's world and then there was your world.

KT: Yeah, it was my studio but once he was in it, it was his studio. That was good. That was a nice experience and I really enjoyed it.

DG: So the Numerals were a really fun series but perhaps Fragments series were a bit more painstaking or exacting?

KT: I think it was more of a chore. More of a chore for him. The Numerals, they really were the ones that I think made the biggest mark in the studio. I mean Bent “Blue” was interesting in many respects because it had a brother and a sister, it seemed. If I had Bent “Blue” framed on the wall and I had Figure 7 framed on the wall, I would keep 7 there and put “Blue” in the closet. I haven't revisited those prints.

DG: I'm guessing you don't have any works by Jasper these days?

KT: No I don't. I went through a rough patch financially and I sold a lot of that stuff. Regrettably. But nevertheless, it was essential. They were the ones that would go fast. So that's what I used for this currency. I had to feed the beast.

DG: I remember you telling me a story in 2018 about [Robert] Rauschenberg being so excited by the Stoned Moon series that he jumped up on the press bed and he…

KT: and he pees.

Robert Rauschenberg observes Daniel Freeman, Andrew Vlady, Bob Petersen, Tim Ifsham, Charles Ritt and Ron McPherson move laminated lithography stone for 'Waves' print from 'Stoned moon' lithographic series onto lithography press bed, in workshop, Gemini G.E.L., Los Angeles, 1969 (c) Malcolm Lubliner

DG: I think you said that [William] Crutchfield was taking photos of that incident and you had to dispose of the film because it was too reputationally incriminating.

KT: It would have been terrible to put those pictures out.

DG: I think after you told me that story, I went back into the archive and I was like, “where are all the Bill Crutchfield photos? Are there any here?” I couldn't see any.

KT: Bill was a fly on the wall in the shop. But that had to be taken out. We did a lot of things. Sweep this and that under the rug and don't let that be put in history books: That was the name of the game. We had a responsible kind of audience out there and we had to make sure that that audience was fed good stuff and not given a lot of secrets. As they were a very noisy group and if it got out there, it would not be good. Everybody knew that everybody was under [the influence of] coke and stuff like that, but there's no evidence of it. If there was evidence of somebody snorting that would have changed the whole scene a lot.

DG: Was that just LA? When you went to New York, was it all a bit more reasonable?

KT: Well, artists would let their hair down when they came to the West Coast.

DG: That was the holiday zone.

KT: It was play time.

DG: It was really fun to research into your collaboration with Charles White, and the Young Woman print and to see the original photograph that it was based on. Before we knew of the revised title, Young Woman, I always assumed that the portrait was of a man. I’m guessing that White was a university contact?

KT: Yeah. He was. That was a guest print… I mean, I did a few but I didn't like doing them. They didn’t fulfill me with a sense of accomplishment and the Charles White is one of those. It happened, but it didn't really have any great effect. But it gets resurrected and all of a sudden it has a very different kind of history. I mean, it's strange in many ways that my collection should be in Australia and not New York City. But in a way I've always been against New York City anyway. So, it’s poetry in a way. [New York] didn't treat me right, so why should I be with you? I want to be with my fellows in Australia. I like them better.

DG: It does have an impact, your collection. There’s a younger generations of artists, one in particular that I'm thinking about, who's quite successful. His name is Tony Albert and he is Kuku Yalanji, an Aboriginal artist. In his work, there’s already similarities with his use of targets and Jasper Johns’ target motifs, and he picks up on Bruce Nauman’s Pay Attention. He sees that in your collection, in your work and in our broader collection, and he starts to feed that into his work. I feel as though your collection has had an impact on the Australian art landscape when I see these works.

Bruce Nauman, Gemini G.E.L., Kenneth Tyler, James Webb, Ronald Olds, Pay attention, 1973, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, Purchased 1973. © Bruce Nauman. ARS/Copyright Agency.

KT: Art does continue on, and it does have a great effect on generations of people. More than we think. If you think of all the iconic images in the art world that you are subject to and ask yourself which one still lives the strongest? It's a game I play. To think about all the past. Every once in a while, it's a Picasso or a Matisse. It's funny [that] Jasper [Johns] and [Robert] Rauschenberg, and [Ellsworth] Kelly and all those people. Not Albers, I mean [Josef] Albers sticks with me in a very strong way.

DG: There are also a group of young Australian artists who really admire both Anni and Josef Albers. They work in that sort of abstract subtle gradations of colour and playing with your perception. I think that's another nice little seed that you've planted in Australia that will continue to grow.

KT: Into a tree like that? [points to Elm in his backyard]

DG: Yes!

KT: The tree of life.

DG: We have the Anni and Josef Albers exhibition coming up, so I guess it would be great to see if that has a resonance with a younger audience. Imogen Dixon-Smith will be curating this exhibition and will be putting all the series you did with them front and centre but then drawing in the connections to Australia as well. So for example the way that Josef had an impact on Harry Seidler, because they studied together.

KT: Yeah, he had a big impact. Harry was quite enamored with Albers.

DG: Did you meet Harry?

KT: Yeah, I knew him. We had quite a nice relationship there. But not for very long. His daughter is quite active, keeping the legacy alive. She communicates with me quite often.

DG: Did Josef ever talk about Harry to you?

KT: Not really… That was a long relationship because it started at Tamarind [Lithography studio] in the 60s. We did a lot of work together. A lot of meals together. Josef and his lunch. Every time he came [to Los Angeles] he was looking forward to going to Nino's, which was the restaurant, the Italian restaurant in our neighbourhood. He just loved having these lunches and going to eat.

DG: Did you ever get that sense, when you first met him at Tamarind, that this was your breakout opportunity to work with a Bauhaus master?

KT: No, I didn’t look at it that way. It was just taken for granted. But don't forget we worked together in the little house next to Tamarind. We had our own little private world and that was nice.

-

Josef and Anni Albers pose for a polaroid photograph. Unknown photographer.

-

Josef Albers and Kenneth Tyler in Alber's Connecticut home, 1969. Unknown photographer

DG: Is that because Josef needed space to work without distraction?

KT: Well, when you are doing, the rest of the shop is not involved in it. There was an awful lot of traffic that was going on there that wouldn't be of interest to Josef at all. It was smart of June [Wayne] to give us that space, because we did some nice work.

DG: Did his colour philosophy make an impact on you at that stage?

KT: No, because I was very familiar with the Bauhaus. Yeah. Don't forget where I came from, the Art Institute of Chicago.

DG: What was Chicago and its art scene like growing up… or should I say East Chicago?

KT: I was very anxious to be out of there. My music instructor in middle school took me under his wing and got me to go to the Art Institute of Chicago on a scholarship for the weekends, Saturdays.

DG: Did you meet anyone in particular there that had an impact on you?

KT: No, no.

DG: Still, that must have been a nice point of relation for you and Joan Mitchell.

KT: Chicago is an outpost in America for art. It was a little village in the midst of a big, big world. New York and Los Angeles are two different art centers and neither one thought much about the Midwest. So, people from Chicago, say, yeah [rude gestures] to you too, you know.

DG: I remember this reading the story that Gemini is starting up and you're putting these double page ads in Artforum. You wander into the office and the young office administrator was Ed Ruscha. Then all of a sudden, you're printing an edition with Ruscha. How did he come across?

KT: Ruscha was a kind of enigmatic person. Even in those days. Whereas Bruce Nauman was uniquely qualified to be an artist, but nevertheless when you looked at him you told yourself ‘this is not an artist’. He didn’t fit the picture. The eastern boys did you know? They were grown to be artists. I saw recently that Pay attention, that print went for a hell of a lot of money. A hundred thousand I think. It gets a hundred thousand dollars. We live in a nutty world.

DG: Did he use stencils? The lettering is quite nice.

KT: No that’s not a stencil, that’s his writing. But Jasper Johns always used stencils. He loved those stencils.

DG: While researching for the exhibition Rauschenberg & Johns, the opportunity to have the archival material at hand really changed everything. You can see the energy that Rauschenberg brought to everyone, to all the printmakers who are standing around laughing as he's pointing at things in his prints.

KT: Collaboration played a very important role in his life. He enjoyed working with other people, with ideas and things. Whereas Jasper was very happy to be the quiet one, he was very happy to be in the corner. But Bob was not happy being in the corner. He didn’t want to be in the corner. He wanted to be at the centre of activity. Making more noise.

DG: I hear that the print sessions went on all night, well past midnight.

KT: Yeah, with lots of drinking. Lots of flirtation.

DG: Did you participate in the drinking?

KT: No, I had to behave myself. To be the monitor, the adult in the room. I let the kids play, but I wasn’t able to play with them.

DG: That must have felt strange, like it was risk-taking to let all the artists drinks like that.

KT: No, I just assumed that was my role. It seemed very natural to me. That I was going to be the senior in the room. After all that's just my domain I had to protect it. Occasionally it got out of line and I had to correct that.

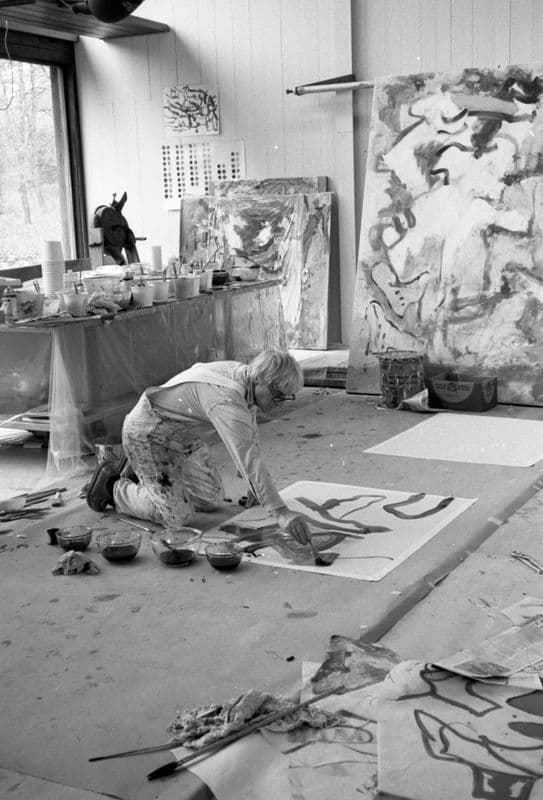

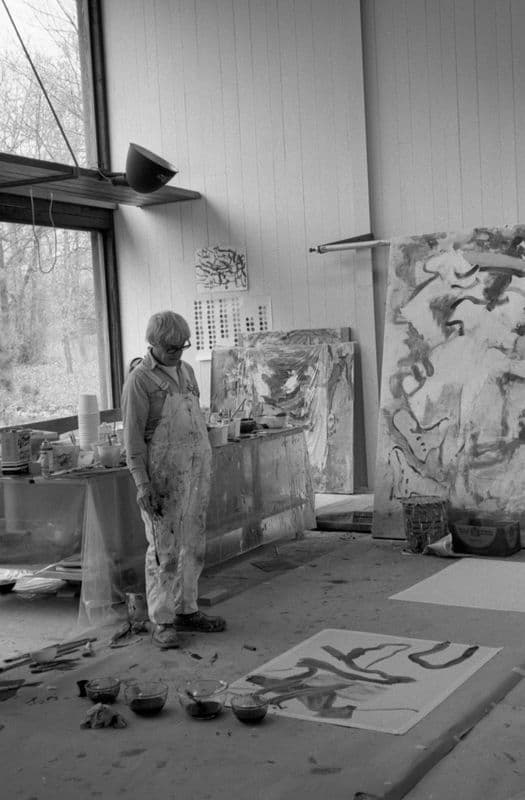

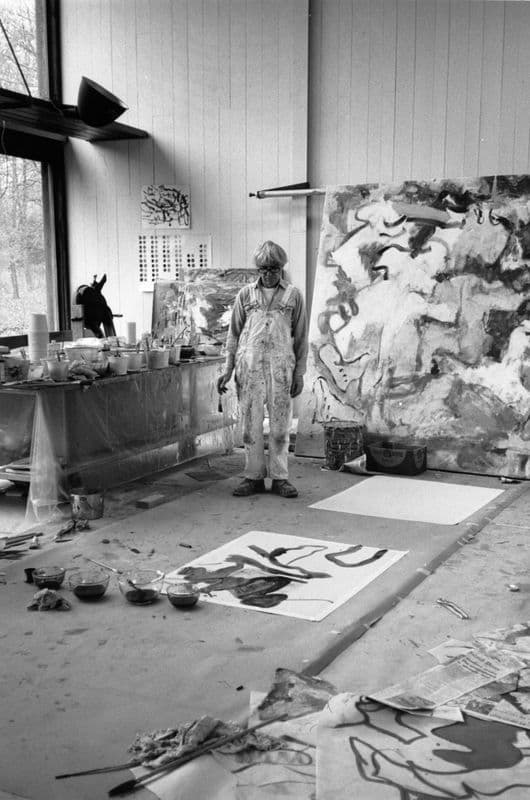

DG: One of the questions that Jane [Kinsman] had is why did Helen Frankenthaler proof continuously but was never quite satisfied, to move on to editioning her work?

KT: Well, that's not quite true, some things came together very quickly and they were editioned and that was it. While other things she played with for quite some time. But that had a lot to do with the visitation, how often she was in the studio, what her life was about as an artist. Whether she had time to be in the studio more often, or not so often, but there were periods when she would come quite often. That artwork was extended into that kind of routine. But if she was only there for a little bit, and she had pieces that she had to work on, that was different. So each one of those prints had their own life. When we did This is not a book (1997), it was incredible, and I never thought it would get done. But it did.

DG: You thought to yourself “This may not be a book”

[laughter]

KT: It was just timing. Remember you had to be in the studio and the studio was not next door. When she stayed over it was fun because we got to drink and have dinner, we got to have chats. Helen was different at dinner than she was in the middle of the day.

DG: Did she become a bit more free and open?

KT: Sociability was important. She was a good conversationalist. A good dinner partner. The playfulness came out.

DG: That dynamic must have been important to keep the work going.

KT: Mind you, we’re talking about Joan Mitchell, Helen Frankenthaler and Nancy Graves. Those were the important female artists to the workshop. They were the three important ingredients in the body work that I made. Of all those, the most magical was Nancy Graves. She was this beauty that appeared, gentle and lovely.

DG: There are some fantastic photos of her at Tallix foundry in the archive.

Nancy Graves inspects a bronze cast of a camel bone, thought to be for her work 'Ceridwen, out of fossils' at Tallix Foundry, 1977 Kenneth Tyler

KT: And also at Tallix with Helen [Frankenthaler]

DG: What was it like, that relationship with Tallix? It was quite close, wasn't it?

KT: That was part of the Tyler collaboration. That was an important place for us to collaborate.

DG: How did you first meet Roy Lichtenstein?

KT: Let's see. It goes back to New York. When Dorothy [Lichtenstein] was working for the gallery. For Castelli.

DG: Then you begin with the Cathedrals and the Haystacks...

Leo Castelli, an unidentified person, Kenneth Tyler, Irving Blum and Roy Lichtenstein view Lichtenstein's 'Haystacks' series, Gemini GEL, Los Angeles, California, 1969. (c) Malcolm Lubliner

KT: Those are the early ones. That was a nice part of being with Roy and printmaking. When he did this series, because it was a lot of time was spent, and it was a concentrated period of time, to get these things done. And then there would be these large amounts of time when he wasn't around. You have to remember that these projects were not a string of events. They just took place, and then there'd be a hiatus between them and another one. And then out they’d go. So it was hard because I had to keep the shop going and keep things going, but I couldn't always have the artist when I wanted them. So I had to make sure that I made good use of the time that I had with him, that we kept the projects going.

DG: Did that mean that you had to look at what Roy was doing and formulate something to hook him in?

KT: The hook was always “let’s have a lot of things going and never finish anything” so there would always be a way to go back in and keep working with them. You had to pay homage, you had to go and visit them often. Sit in the studio often. But it was fun. It was always fun because when I visited Roy and Dorothy, I'd sleep over so that I had this kind of relationship where we were friends and then we were collaborators. We were business, but we weren't business.

DG: I found some photos in your archive of you at Roy and Dorothy's house at Christmas time. You're all sitting around playing chess together. There are these beautiful shots of the snow falling outside. You can sense the friendship.

-

Roy Lichtenstein plays a game of chess with an unidentified individual in the loungeroom of Roy and Dorothy Lichtenstein, Southampton, New York State, 1976. Kenneth Tyler

-

A flurry of snow blankets the road as Kenneth Tyler drives home from Roy Lichtenstein's house around Christmas time, Southampton, New York State, 1976. Kenneth Tyler

KT: I was thinking about that the other day. It’s funny that I don’t see Dorothy very often. You think that I'd be seeing her more, but I live here and that’s New York. New York and I have this strange relationship.

DG: I understand. It's a bit of a clusterfuck at times.

KT: Yeah. It is. I know.

DG: It's interesting to see that Roy came across with you from Gemini GEL to Tyler Graphics, but other artists like Rauschenberg and Johns seemed to have stayed on the West coast with Gemini. Was it difficult to convince people to come on across to Tyler Graphics when it first started?

KT: Tyler Graphics was like a very secluded country that they were coming across to. It was not always their cup of tea. There weren't collectors hungry for them to come for dinner, it wasn’t a part of their social life. They would be going into a situation where there was no social life and social house if you wanted to come for dinner. You go to the apartment and be a solitary monk. It was a bit of a struggle to keep it going because I knew that I was the gregarious one, my wife was not, so I had to entertain them and do the work and make it all happen. So there were periods of time and the work would get going and then they would disappear. Then we would finish the work and they would reappear. In the country, you could really only have one artist at a time. Because you couldn't socialise. There's no scene beyond that. There were no collectors that I could rely upon to take them to dinner and entertain them, so that I had some peace and quiet. It was a burden, and I'd burn out very quickly.

DG: When I look at it all, you seem to set up in Bedford and there's this moment where you're starting to get the wheels turning: You've got this fresh memory of going to Richard de Bas paper mill in France with Rauschenberg using tin moulds. Then Ellsworth Kelly is one of the first artists to come and visit you in Bedford Village. He starts to play with the tin moulds. Ellsworth was all about clean lines…

-

Gianfranco Gorgoni takes photographs of Robert Rauschenberg while he creates 'Page 2' from his 'Pages and Fuses' series, at Richard de Bas papermill, Ambert, France, 1973. Vera Freeman

-

Kenneth Tyler applies a vivid red paper pulp to a carrier sheet during the production of Ellsworth Kelly's 'Colored paper image IV (red curve)', 1976 Photograph by Betty Fiske

KT: That stuff we did with Ellsworth was pretty fantastic. But Ellsworth didn't think so. This is something… the dynamics. There's been no critic, no one that has really looked into this: This work that I did in paper pulp was a challenge to the artist, but there was also a fear that it would take over. This was to too much for them. It almost bothered the sanctity of their private life, that they were giving up to do these multiples, especially the paper pulp stuff. Because they couldn't do that. Like the wonderful story of James Rosenquist going back to his Tampa, Florida house with a pattern pistol and in the driveway trying to do a paper pulp piece but it didn't work for him. And he admitted the fact that he couldn’t do it: “I tried to do this myself. I couldn’t goddamn it. I need you Ken!” That's good, don't worry about it Jim. It's okay to need me.

DG: So, the Kelly's are there and I presume that they are drying on the felts and then you say to David Hockney, come up and have a look. Was the hook for David his enthusiasm for the paper? Or was it for Ellsworth's work?

David Hockney pressing colour pulp into a mould for experimental paper pulp work (never published and destroyed) during the 'Paper Pools' series, Tyler Workshop Ltd. paper mill, Bedford Village, New York, 1978. Photo by Lindsay Green.

KT: I think it just was a moment in time for David to be away from his groupies and to be back with me, working. We like each other and we like working with each other. That was a lovely moment in time. It was lovely that Lindsay [Green] was there for that period, because I needed help. She was there and that was good. There are a lot of very pleasant memories for me during that workshop period, that period of our lives. There's this one picture I took of David holding up the [Camp Wonderful] sign. That's what it was. It was Camp Wonderful. So there's Lindsay and I, with our romance going on, and there's David, the three of us and we all have these different roles. We're all playing this part and we're doing this work.

DG: It feels like it was a golden moment.

KT: We were working into the wee hours of night. We were over there drying the felts and hanging stuff up and you get to the point where you're so tired that your nerve endings are just so raw from this creative act going on. It was so fantastically gratifying. It would be hard for anyone on the outside to know. It was like having 24-hour sex.

DG: Exhausting but amazing?

KT: Goddamn it was good. Because we had 25 gallons of this [colour paper pulp] and 25 gallons [of this colour paper pulp]. 100 gallons over here that we couldn't use because we didn't quite make it right. There was all this stuff going on. In the meantime, you're sleeping, you're eating, you’re having conversations with people and the world is continuing to spin on its axis, but this art is getting made. It's getting made in the most enjoyable way and that’s the only way I can explain it. Camp Wonderful it was. I think those pieces are love pieces. They really are. You could just feel the loveliness of paper pulp being made and being put into frames and being put out on the platform.

DG: Do you remember the moment when either David or yourself said “let's do away with these cookie cutter moulds”? Let’s make it about the liquid medium and the way the paper pulps can bleed into each other?

KT: Well, it happened right away. There were 20 or 30 of these large pieces. It was a lot of work.

DG: It was in 2018 when I started working with your archive at the National Gallery. I remember the Director, Nick Mitzevich, saying that he wanted to know more about the Tyler archive. The one thing that I decided to show him was to demonstrate how the Polaroids in the collection are the source material for ‘A diver 17’ in the collection. I could see Nick’s eyes light up when he could see the correlation between the artwork and the source material.

KT: My only regret is that we didn’t have the ability to film more than we did. But somehow there are certain moments when I just said to myself that this is really milking the cow a little bit too much, we don't want to be documenting that closely and that much. It makes it just a big act, like we are pretending. I talked with the cinematographer quite a bit about this, it was always the same: Everybody wants their piece of the action. When you have a cinematographer around, they want to really get all the subject matter to themselves. Because that's their job. So it's an intrusion. There were a few times when Gregory [Evans] would try to come over with a camera and photograph us working together. That didn't work. Maybe because of the relationship between Gregory and David. It made it too much of a fun job and not serious enough. Bringing other people in was better and that seemed to have some good effect. It was always a dicey game we played with the public. Whether we let them in, or not let them in. I always felt like a guard dog.

DG: I remember seeing photos of Paper Pools being made outside the garage, and there does seem to be someone filming. They are atop a ladder. Who was that?

David Hockney and Kenneth Tyler working on the pulp moulds for one of Hockney's six-panel pools from his 'Paper Pools' series with Larry Stanton and Arthur Lambert observing, Tyler Workshop Ltd. driveway next to paper mill, Bedford Village, New York, 1978. Lindsay Green.

KT: That was a friend of David.

DG: Does that footage still exist?

KT: That was the friend of David… From [Henry] Geldzahler. He was one of the boys. It was hard for me to keep all that together because it was an open house. It got messy.

DG: I’d been interested to track down that footage, wherever it may be. So it might have been from Henry Geldzahler?

KT: It was a lover of Henry’s. It’s funny, most of those hanger-ons were like cut-outs. They weren’t real to me. They had to be there for some reason, I guess they were significant others to these people. I accepted the fact that there were going to be these people around and there would be nothing I could do about it. They got in the way, but would want to be a part of it, but I had to keep the work on track.

DG: That reminds me of that quote that you were the 'Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer', the director of the set piece. Hockney’s the main actor, but then there are all these props in the background crowding the scene.

KT: Gregory was a sweet guy and most of the times he was very valuable to the whole operation, because he kept things going for David and he was fun to have around. Henry Geldzahler was definitely a nuisance. I’ll never forget the day that he was in the studio tearing up some of our Paper Pools. He was playing ‘Mr Editor’. I lost several Paper Pool pieces because of that. He was playing Mr Editor, that was his job, his role. Things bite the dust. There are these wonderful pictures of David and I and the metal frames that we're doing. This one little picture with a tie. It was Henry who put the kibosh on that one. This is just destiny, it’s what you must deal with. Art is a very fragile thing when it's being made. Most people just don't understand it because they don't do it themselves and they have no way of knowing it. But the amount of intelligence and energy that goes into making every one of those pieces is immense. It's a lot of heavy-duty concentration.

To throw that into the garbage is painful as hell, because you want it to live, you want it to have its life with someone. You want to make sure that it is given all the nourishment that is needed to become a piece of art.

To have an outsider come over and just throw that away. It’s insanity. But I also remember that [John] Kasmin once told me that David [Hockney] needs to be edited.

DG: I have seen some of the Polaroids for abandoned works [by Hockney] and I can see that. Some works just fall flat.

KT: Not everything is going to be great. Some of this stuff is like a signpost along the way. It's useful to keep that stuff and keep it in order. It is a kind of capsule. On one hand you have to say it's good to be an editor. On the other hand, it's not good. It all should be kept and then given some space to live or not to live. To look at it, maybe a year later, and decide whether you should throw it away.

DG: When Hockney gets into the faxes, it's keeping him away from you and your studio because he becomes obsessed with faxing.

KT: David is the compulsive maker. Once he gets going, he just can't stop doing it. It’s like him smoking cigarettes.

DG: So you begin making the Xerox toner powder chalk with Nick Semenoff. Were you getting more subtle line work from them? Or a texture?

KT: They were just another extension of us trying to get another print out of [David Hockney]. Trying everything.

DG: There weren't many other people who used those?

KT: No. We ran the Xerox powder one into the ground. There are a couple pieces that they did.

DG: It was Mnemosine by Hugh O’Donnell. He used those chalks too.

KT: Mr. O'Donnell. There was one artist who I thought was a great collaborator, and that was [Robert] Zakanitch. We did some very nice things together. It was this innocence.

DG: How did you meet Zakanitch?

KT: I think it was through Barbara Rose. I can’t quite put my finger on it, but I think that she was the one who introduced us.

DG: He was part of the ‘Decoration’ art movement. There are beautiful photos of him sitting on the steps near the workshop, surrounded by a structure for climbing plants.

Robert Zakanitch outside the artist studio during the ‘Paper pulp’ and ‘Double peacock’ projects, Tyler Graphics Ltd., Bedford Village, New York, 1981. Lindsay Green

KT: That was our trellis.

DG: I've got a visual sense of how everything was in workshop, but I never ever saw it.

KT: You have this memory. Looking for the secrets are you?

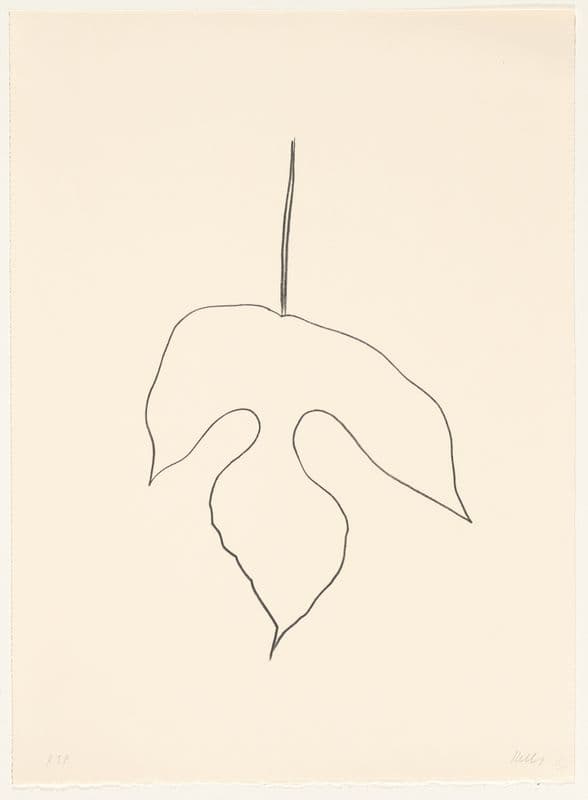

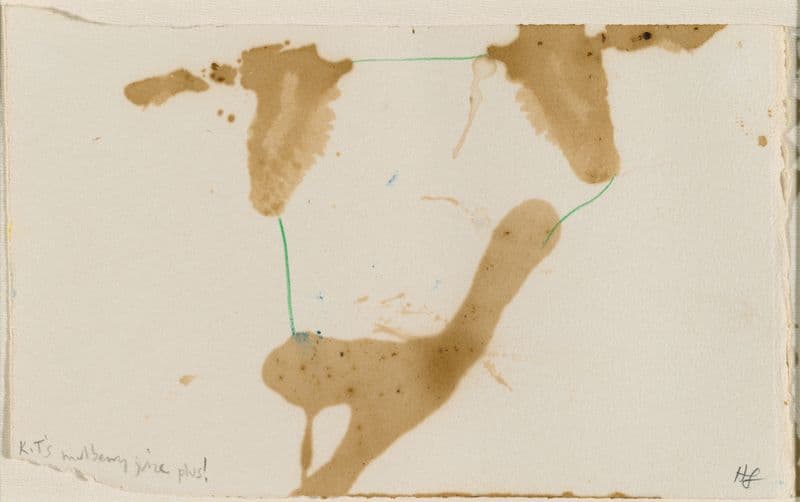

DG: One of the beautiful links that I’ve seen from your garden is Helen Frankenthaler doing ‘K.T’s mulberry juice plus!’ out of stained mulberry juice and then you've got Ellsworth Kelly drawing the leaf of the same mulberry tree. I love that.

-

Mulberry leaf, 1980. lithograph. © Ellsworth Kelly. Purchased 1980. Ellsworth Kelly

-

K.T's mulberry juice plus! mulberry stain and coloured pencil on paper. 1977 Helen Frankenthaler

KT: Yes, the workshop was located in a peculiar little time capsule. It was the country. Actually, I gave that one beautiful little drawing that [Helen Frankenthaler] did with mulberry juice to the National Gallery of Australia.

DG: Yes, that's with us.

KT: Better that you have it than the auction house. It was always a question I had: What do I put aside and give to the National Gallery [of Australia]? Basically, all the artists were very generous about giving to the museum. They didn’t object to that.

DG: It's a time capsule. I’m always astounded at the stories that I can discover within the photographs. For example, R.B Kitaj, who began to date your personal assistant at Gemini.

KT: Ah Mr Kitaj. A bad boy. My intuition was correct. Then they had a child.

DG: That early Gemini Limited period is interesting because you work with so many artists in such a short period of time and often the artists you work with in those early years only produce one thing.

KT: It was a scramble to keep alive. It was a scramble to get money. Trying to figure it all out.

DG: When I think of your overall collection, there are around twelve artists who are always there and are deeply a part of the story of your workshop. But there are these others right at the start of your career who are just a flash in the pan.

KT: The interlopers. The ones who came in to get some notoriety. Usually artists don’t bring in anybody. But David Hockney did bring in Patrick [Proktor]. He did that one big print. That was like, okay, phew, I got rid of him. I always thought the workshop was a great subject for somebody who really wanted to look at the making of art. What does it take to make a piece of art in a collaborative way? Why is it more interesting when it’s collaboration instead of a solo artist, making something by themselves in a corner. But it's complicated for a lot of people who aren’t involved in the art world to understand the workshop and I've had conversations with people who ask, ‘Why did that happen?’

Well, if you put creative people together, these things happen, if you let them happen. Then you have this wonderful history.

Other people didn't do it. Well, it’s because they didn't have a workshop. It's as simple as that. You need the workshop. All the people in the workshop, they make a difference.

DG: I always think about your collection as a complex web where nothing is necessarily isolated from anything else. It all links through different collaborations and through the development of different techniques. It's a whole.

KT: That’s right, there is a thread that keeps it together… It’s an activity that I miss.

DG: I tend to think of [Frank] Stella being the strongest thread that runs the entire way through.

KT: Recently Frank said to me ‘We need to do a project again soon’. I said ‘I'm getting a little bit rusty and old Frank. I don't know if I can do it again’.

DG: I think you could do it Ken. Why not?

KT: It's not as simple as that. I struggle for, I don't know, maybe a month or so with this same [inaudible] like ‘okay what can Frank and I do now’. But there's no workshop. What can we do? I don't want to move into Frank's space. That's too far away. There are all these possibilities, they're not real possibilities, they’re just thoughts. The stars are not in alignment. You can't resurrect time.

DG: I'd love to just be a fly on the wall while you and Frank have a conversation. That would be magical. You both have such a long history.

KT: You'd be amazed how much grunting goes on. You can only be a scholar for so much.

[Laughter]

DG: A grunt translator.

KT: You know, when you work together so much as we worked together, you do form a kind of relationship which is about grunting. You don't need words. It's nice to have them. I miss those grunts.

DG: Did you ever have a moment of realisation, that suddenly a new movement, the Pop Art movement, had emerged?

KT: You know, memories are strange things. Sometimes your memories are correct but sometimes they aren’t because they are made up. The subconscious needs to piece things together. Sometimes the memory is a faulty thing and it sets up an interesting dynamic where you thought something was true, but it wasn’t true at all.

DG: Like when there are photos of that time, you begin to only hold onto memory where the photograph acts as a kind of stand-in. The documentation prevents it from fading into obscurity.

KT: Absolutely.

DG: Did you sense this from the beginning, in the studious way that you built up your archive?

KT: I don’t know if I knew that or simply thought of that retrospectively. It just seems like it was destined to be. I take great comfort in knowing that all those parts and pieces are at the National Gallery.

DG: It means that it’s still alive. I always think of it like blowing on the hot coals of a fire.

KT: Too bad it’s all the way over there in Australia. Filled with snakes. Some of the worst venomous things in the world are there, along with my collection.

[laughter]

DG: Early on, how did you get into the steel business? Through your Dad?

KT: Well, I didn’t get into the steel business. I was in the sales part of the steel industry.

DG: Was it the U.S Steel corporation?

KT: No, it was carbon steel and carbon wire [inaudible]. It was strip steel and wire. I worked on the IBM Selectric typewriter’s steel which was quite an adventurous time for a while.

DG: It’s great that your association with steel fed into joining the Engineers Corp. Did it also feed into working with the manufacturers to develop the ball-grained aluminium plates?

KT: Oh yes. I travelled seven states for sales and so I saw a lot of manufacturing. All sorts of manufacturing, from little stuff to big stuff. It was great and I enjoyed it a lot. It added to my interest in metallurgy, chemistry and how things go together. All that was fascinating to me. In many ways, even though I was burdened with a lot of travel, I made a lot out of it. I got a lot out of it. When I went back to art school, I was a ‘senior senior’ and that was interesting, I felt like grandpa among all these kids. It was a very unique experience. I had a good education when I started out, but then going back to school as a senior was interesting. I fortunately met William Crutchfield and we became buddies and all of a sudden a few years went by and I was out of it.

DG: Bill must have been a wonderful teammate.

KT: He was my sidekick. We had a lot of fun together.

DG: In terms of your experiments, I read a snippet from Jasper Johns about your use of alabaster to see if it could function as a lithography stone.

KT: It didn’t. It had the wrong density for absorption.

DG: Do you remember what Johns started to make on the alabaster? Was it the numerals?

KT: Oh no he didn’t work on it. I was working on it. The results were too uneven. It’s not something I wanted to see anyone labouring over only to have it destroyed because it couldn’t hold it together. Alabaster was not the right type of absorption for the stone. It couldn’t retain the grease for a great time. It would release it. These were strange experiments, as if we couldn’t afford a new piece of limestone. It’s like all the lumen tests we used to do: playing around with this and that, when you could just buy the ball-grained plates. We were trying to invent the wheel when the wheel had been around for a thousand years.

DG: What about your experiments in using mylar as a sketchpad for lithographs?

KT: mylar was a discovery that was a means to an end. There were so many possibilities. The best thing was that you could just put a big sheet on the wall and the artist could just draw away. It was very expedient and right to the point. You could just move it into the dark room and expose it, wipe the plate and just play around with it for a while. That was it.

DG: When did the mylar experiments start exactly? I ask because I was looking at Keith Sonnier’s Video Still Screen series from 1973 and that was a screen print on top of mylar.

KT: Yes, but that was not mylar as a printing element, only as a substrate. Mylar has been around since the 50s or 60s, but all of a sudden it took off around the early 70s as a material. For me it was great because it was something the artist could use to figure out colours.

DG: It solved the problem that you came across with de Kooning in 1971.

KT: Yes, a lot of artists can’t separate the colours in their head. Because they aren’t trained to. Layers is something that a technician gets involved in, but artists don’t. They don’t realise that the layers that you’re putting down, if you took away some of the layers underneath it would be a completely different picture. mylar would show you that pattern of work and that was very in itself. You could see that you needed to lay down a little bit more yellow to begin with, and you could play around. It made everything faster and more uniquely creative. You didn’t have to wait around for days, you could just do it yourself. Off you went into the printing studio.

DG: So the first people to use your textured mylar sketchpad was Joan Mitchell in 1981?

KT: Yes, she was one of the great proponents for its use. As time went on I did more and more experiments, making mylar in all shapes and forms and making it with all sorts of texture. When I got involved with textured mylar, things changed quickly. It was a big breakthrough.

DG: I love the sketchpads.

KT: They helped David Hockney a lot. It was brilliant to think of a mylar sketchpad, because afterwards we also still could keep the sketches. I think Australia has one?

DG: Yes we do. It’s a great invention, how easily an artist can see through the layers of their sketch and then when you compare that to your early experiments with Willem de Kooning, where there are photos of him with three separate plates, one for red, one for yellow, one for blue, on the floor in front of him. You can see that it doesn’t gel for him.

-

Willem de Kooning, 1971. Kenneth Tyler

-

Willem de Kooning, 1971. Kenneth Tyler

-

Willem de Kooning in the studio, 1971. Kenneth Tyler

KT: Yes, most artists don’t think in layers and it was something that I learnt very early in my collaborations. Sometimes you had to talk to the artists like they were kids, explaining how the colour separations worked.

DG: You have a de Kooning painting on plastic. How did the transfer of de Kooning’s painting onto plastic work? Was it just a monotype? Or were you thinking of making it into a print and editioning it?

KT: I was thinking of editioning it. I actually made all the plates, separating out all the colours, but it didn’t work. It wasn’t a de Kooning. It was too busy. It was uncharacteristic. At least in the mylar you can see the artist’s hand, the brushing.

DG: Was the de Kooning coming across a bit flat when you translated it to a print?

KT: Yeah it just didn’t translate. The nuance is just so important. Now if he was making a print from the start, and we got him to think in layers that would have been something else, because I’m sure de Kooning would have changed his drawing habits as he went from colour to colour.

DG: If you sat down with de Kooning and said ‘I want you to change the way that you think about making a work’

KT:...and it didn’t work that way, because when I sat down with de Kooning all of a sudden we were talking about Albers, Kelly, Picasso. When I brought up the plates it was a matter of ‘let’s think about that later’.

DG: The photos that you took of de Kooning’s studio, the [de Kooning] Foundation now look at those photos to help identify authentic works in people’s collections.

KT: I had a cellophane personality that not many people know about, where when I visited artists I just melt into the woodwork.

I should have taken more photographs, because I was there at the most opportune moment. I was a fly on the wall.

I didn’t impose myself in any way. I was free to roam, but I thought it felt like an invasion of privacy to photograph, and I didn’t photograph things like his hand moving the tusche on the plate. It somehow didn’t feel right. After I was out of there I regret that I didn’t. It’s so funny how the mind works. You think you have these ethics.

DG: We can always just imagine those photographs… Tell me more about working with Ed Ruscha. There’s only the one print by him.

KT: Ed was already established and famous. He was on upwards swing because he was adopted by Castelli early on. The early Ruscha exhibitions were very popular. Every mark he made was worth a lot of money, so he wasn’t going to play around in the workshop. He didn’t necessarily believe in edition printing.

DG: Is it true though that lots of lithography stones went into the construction of the Cincinnati freeway?

KT: That’s true. Unfortunately that’s true. The Palm Brothers were a very large printer, commercial printers, who were in Cincinnati, Ohio. Of course I got wind of it, and I wanted to get some of those stones. The person I was in contact with said, ‘well you’d better come because they’re just about to sent off to be ground up for use in the freeway’

DG: Really!

KT: Really. I had a Volkswagen bus and he said that I could have whatever I could put on the bus so I put as much as I could on, until the springs were completely flat.

DG: And so you drove all the way home at 2 miles per hour?

[laughter]

KT: I did get some very beautiful 52-inch stones. Four of them. They became the stones that Jasper [Johns] loved and would print on. That was a great experience. One of my classmates, Georgia Page and myself went off to Cincinnati to get them. They gave us this iron pipe and we had take the iron pipe and put the stone on it, roll it, stop, move it again. It took us forever to move these two goddamn stones. But we did run away with some very beautiful stones. Michael Crichton did a very beautiful piece about Ken and the stones. I don’t know what happened to that. He was just cracked up with laughter when I was explaining what I had to go through to get them. And of all things I had to drive them in this damn Volkswagen bus. Not a truck, a Volkswagen bus. What can you do with that? You can only put so many in until you can’t go anywhere!

[laughter]

DG: Sounds like an adventure. So how did you meet Michael Crichton?

KT: He was going to do a profile on me, but it didn’t work out. He had a lot of conversations with me, but what happened was he started talking to Jasper and Jasper gave him permission to talk some more and to record it, so quickly it became a piece on Jasper and not me.

Michael Crichton, Kenneth Tyler and Jasper Johns at Gemini GEL, 1971. (c) Malcolm Lubliner

DG: But you play a big part in that book.

KT: But that’s okay. That’s just the way that things go.

DG: How far do you think he got into his manuscript on you?

KT: I don’t know. This was a sidekick for Michael.

DG: What was Michael doing otherwise?

KT: Writing novels. And then getting involved with Jasper and was able to produce that book. That’s when he moved out here. It wasn’t far from here. With his new wife and child. It was a town near Bedford.

DG: He started the Stoned Moon publication, but that never got published. Was that just because he wasn’t happy with the end product?

KT: Michael wasn’t devoted to doing this. These were extra-curricular activities. It wasn’t something that he was really committed to doing.

DG: I’m not sure why he wouldn’t publish that piece.

KT: It’s hard to put yourself into someone else’s head. Even when you think you know them. They can wander off somewhere else and you wouldn’t know it.

DG: So, there was Michael and there was Barbara Rose, and they were the dedicated writers for you? Barbara seems to be right through your history.

KT: Yes, she was around for a long time. But she only wrote when she felt like it. There were moments when she was on the tear, and other moments when she wasn’t. Judith Goldman was the same way. She would all of a sudden be intently interested and writing like crazy, and then all of a sudden would disappear. It would be a while until you heard from her again.

DG: Most writers were writing project by project, but then I get this sense that [inaugural print curator at the National Gallery of Australia] Pat Gilmour was writing with a concern for the bigger picture of printmaking.

KT: Yes, well Pat wrote the book. She was going to do some more. She too could rush things. We were doing well and having good interview sessions and then all of a sudden, a publisher could put the squeeze on her and she would have to get the damn thing done. The book was ended prematurely. There is a lot of ground covered in her interviews that were not published in the book. It’s tough, there are these writers who need to get paid for their work but get paid nickels. They get harassed with due dates that aren’t good for the book. You need time to write it, but you also need time to reflect on it. There needs to be a trial balloon that gets sent up. Is there an audience for this? If you don’t do that, well then you’re not satisfying yourself as a creative writer. I have a lot of respect for these people who take on these jobs that pay pennies.

[recording end]