Top picks from the National Collection

Brett Whiteley, Interior with time past, 1976, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1978 This work appears on the screen courtesy of the estate of Brett Whiteley.

Sharing the National Collection curator, LEANNE SANTORO, shares her favourite finds in the National Collection available for loan.

Basin Creek burn, Matthew Barney

Basin Creek burn, 2018 is a unique and very physical sculpture, formed from a giant tree burnt by lighting in the Sawtooth Mountains, Idaho, in the north-western United States.

The detail of the casting suggests an ancient artefact from another era: the contrast between the more organic main section and angular, rifle-handle-like end is striking.

Matthew Barney’s work appears as a piece of specialist equipment perched on a customised stand. The sculpture is part of larger multimedia project, Redoubt 2016–19, exploring the natural world and the human condition.

‘Redoubt’ refers to the defensive military fortification associated with the American survivalist movement.

Matthew Barney, Basin Creek burn, 2018, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased in celebration of the National Gallery of Australia's 40th anniversary, 2022 © Matthew Barney. Courtesy of the artist; Sadie Coles HQ, London; and Gladstone Gallery, New York

In a Latin Quarter studio, Agnes Goodsir

Paris was the place to be in the 1920s.

This was especially true for adventurous artists, writers and performers, who flocked to this ‘City of light’ in the years following the First World War. Agnes Goodsir, an Australian by birth, had come to know Paris well. This is one of several major portraits of the ‘modern woman’ that Goodsir painted in Paris during the mid-1920s.

Goodsir lived her own life outside the confines of traditional roles assigned to bourgeois women. She left Australia in 1900 and established herself as a professional artist in London and Paris, exhibiting throughout Europe in the 1920s. Goodsir led an unconventional personal life through her close long-term relationship with her studio model and companion, ‘Cherry’ (Mrs Rachel Dunn).

Agnes Goodsir, In a Latin Quarter studio, c.1920-22, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1978

Fetish, Inge King

Fetish is a work of immense strength and dynamism, which pulls the viewer towards it as though it was a sacred shrine. In certain African cultures a fetish priest is a chosen person who mediates between the spirit world and living beings.

This sculpture is a remarkable optical illusion of both concurrent flatness and volume formed by the clever conjoining of two ovoid shapes melded together by a central axis.

It is part of an important cycle of Inge King's large-scale sculptures where circular forms are suspended within a vertical framework.

Inge King, Fetish, 1984-85, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, gift of the artist 1995 © Inge King

McHelter skelter, Jake and Dinos Chapman

Jake and Dinos Chapman rose to prominence in the 1990s as part of the Young British Artists (YBAs) and have created a career from truly ‘shocking’ work that explores death and destruction, horror and the grotesque. With few stylistic comparisons, the Chapman Brothers have become known for an aesthetic of total nihilism.

The sculptural vitrine McHelter skelter demonstrates the intense pessimism that exudes from the artists’ best work. Functioning to ensnare the viewer in a moral dead end, the works are diabolical depictions of evil. Yet we are engrossed in the labour-intensive detail and drawn into the repulsive repetition of the infinite, and admittingly highly inventive, ways to die. Worse still, the Chapman Brothers prompt us to smirk at the apparent ideological warfare playing out between two incarnations of pure evil: hundreds of Nazi soldiers, the wartime spectres of twentieth-century history, and several Ronald McDonalds, the immediately recognisable marketing characters of the globe’s biggest fast-food chain.

There are no ‘goodies’ here, only ‘baddies’, with each and every individual barbarically maiming and inflicting death. We are implicated in this horrific allegory through our very looking. An invitation to participate is followed with a swift punishment: we can’t easily shake such a cataclysmic vision.

Jake and Dinos Chapman, McHelter skelter, 2015-16, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, gift of Steven Nasteski 2020. Donated through the Australian Government's Cultural Gifts Program. © Jake and Dinos Chapman

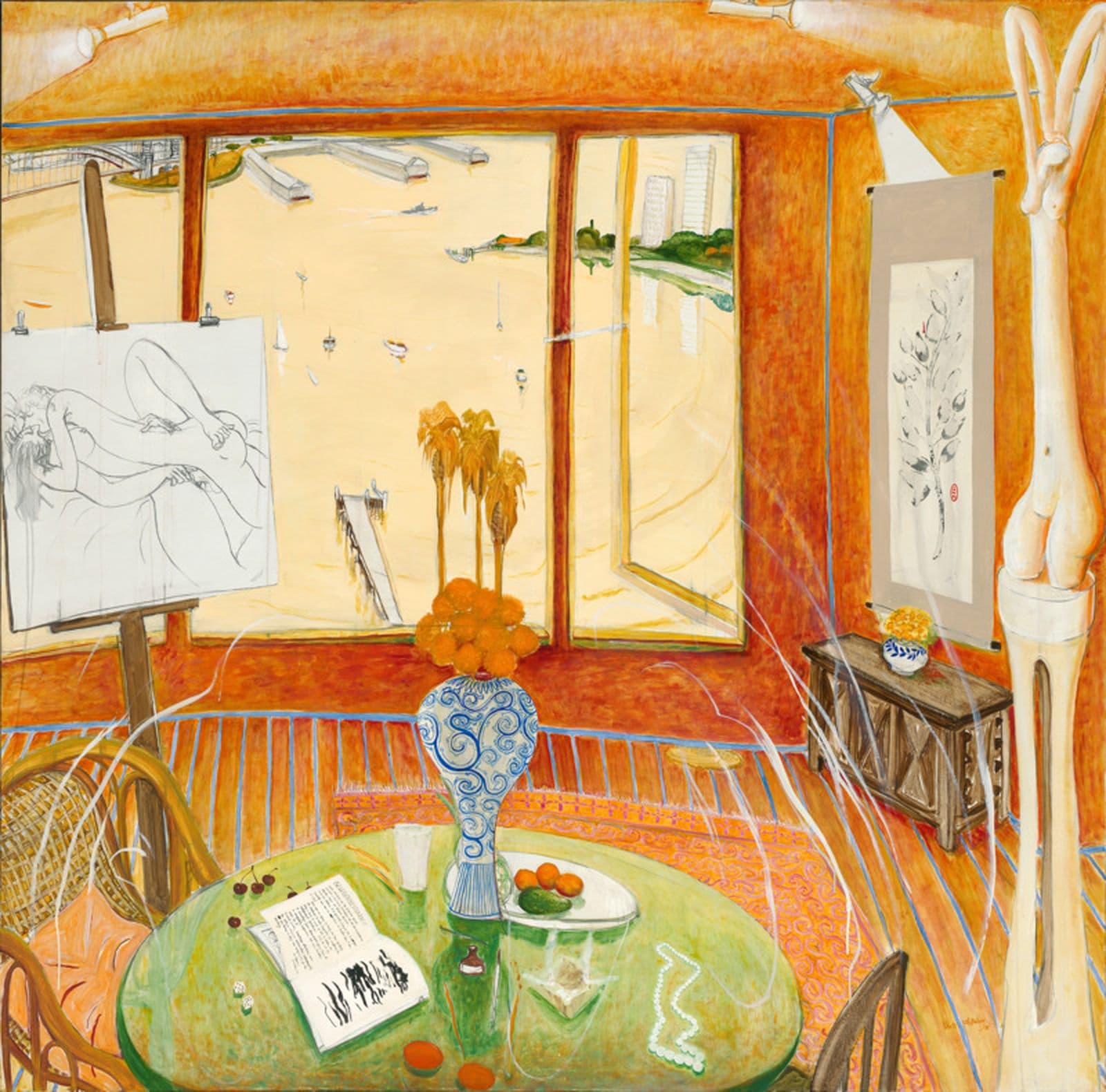

Interior with time, Brett Whiteley

Interior with time past gives us a glimpse into the private world of Brett Whiteley. The setting is his studio at Lavender Bay, with its expansive views across Sydney Harbour. Into this space he has included images of his own drawings and sculptures and, in the foreground, a still life with cherries, avocados and a vase of flowers.

From the drawing on the easel of the couple making love, to the sparkling harbour view, to the still-burning cigarettes, Whiteley evokes a sensuous world of pleasure. Yet, like all still lifes, Interior with time past reminds us that these are all transient moments to be enjoyed, that soon the fruit and flowers will wither, the cigarette will be extinguished, and the lithe young lovers will grow old and die.

Brett Whiteley, Interior with time past, 1976, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1978 This work appears on the screen courtesy of the estate of Brett Whiteley.

Waiting for the train, Jeffrey Smart

Many of the figures in Jeffrey’s Smart's paintings appear to be waiting or watching. In Waiting for the train, a comparison with Samuel Beckett's Waiting for Godot is evoked and a sense of time standing still and the interminable waiting for banal and everyday things to occur becomes the subject of the work.

The knot of figures poised on the end of the platform are in silhouette, save for one whose face seems to catch the last of the sun before the foreboding rain clouds open.

Jeffrey Smart, Waiting for the train, 1969/70, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, gift of Alcoa World Alumina Australia 2005 © The Estate of Jeffrey Smart

Kuru Ala, Maringka Baker

In many of her works, Maringka Baker uses vibrant, contrasting colour combinations to create shimmering, mesmerising works that depict aspects of her country and its ancestral connections. In Kuru Ala 2007, Baker masterfully combines rich, vibrant reds that sit adjacent to shimmering greens, bordered by fine oranges and creams, reminiscent of the desert in full bloom.

The Seven Sisters story is a common one told around the world and relates to the Pleiades constellations (Women) and Orion (Old Man) star. For the Pitjantjatjara the Seven Sisters story is sung at inma ceremonies, which extend into the night. It tells of seven young women being pursued across the sky by an old man named Wati Nyiru. Wati Nyiru is looking for a wife and tries to trick the sisters by adopting several disguises. The sisters hide in a cave and Wati Nyiru tries to block their exit but to no avail—they escape down a tunnel. Wati Nyiru is angered by his fruitless pursuit of the sisters and finally ‘sings’ or makes one of the sisters sick through sorcery. When she dies, her sisters carry her up to the sky where they all became the stars that form the Pleiades constellations. Wati Nyiru also transforms into Orion, a lonely star that constantly follows the sisters.

Maringka Baker, Pitjantjatjara people, Kuru Ala, 2007, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2007

© Maringka Baker - Tjungu Palya

Men's wear, John Brack

John Brack enjoyed creating visual conundrums in his work—between inside and outside, reflection and reality—to question the very nature of representation in painting. In Men’s wear, his first major painting after leaving art school, Brack contrasts an elderly and dour proprietor with a row of inanely smiling shop dummies. A mysterious silhouette in the mirror provides an unsettling note: it is a self-portrait of the artist but can also be read as a reflection of the viewer looking at the painting. The mirror disrupts the illusion of space within the scene, for it is at the rear of the shop, defining the spatial depth of the picture, but also purports to depict what is outside the space of the painting.

Brack was born in Melbourne. After service in the Second World War, he studied at the National Gallery School and lived in Melbourne for the remainder of his life. His sharp observations of suburbia established his reputation as one of Australia’s greatest painters of the modern urban condition.

John Brack, Men's wear, 1953, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1982 © Helen Brack

Expressions of interest for Sharing the National Collection are open now, apply here.