(W)holes of existence

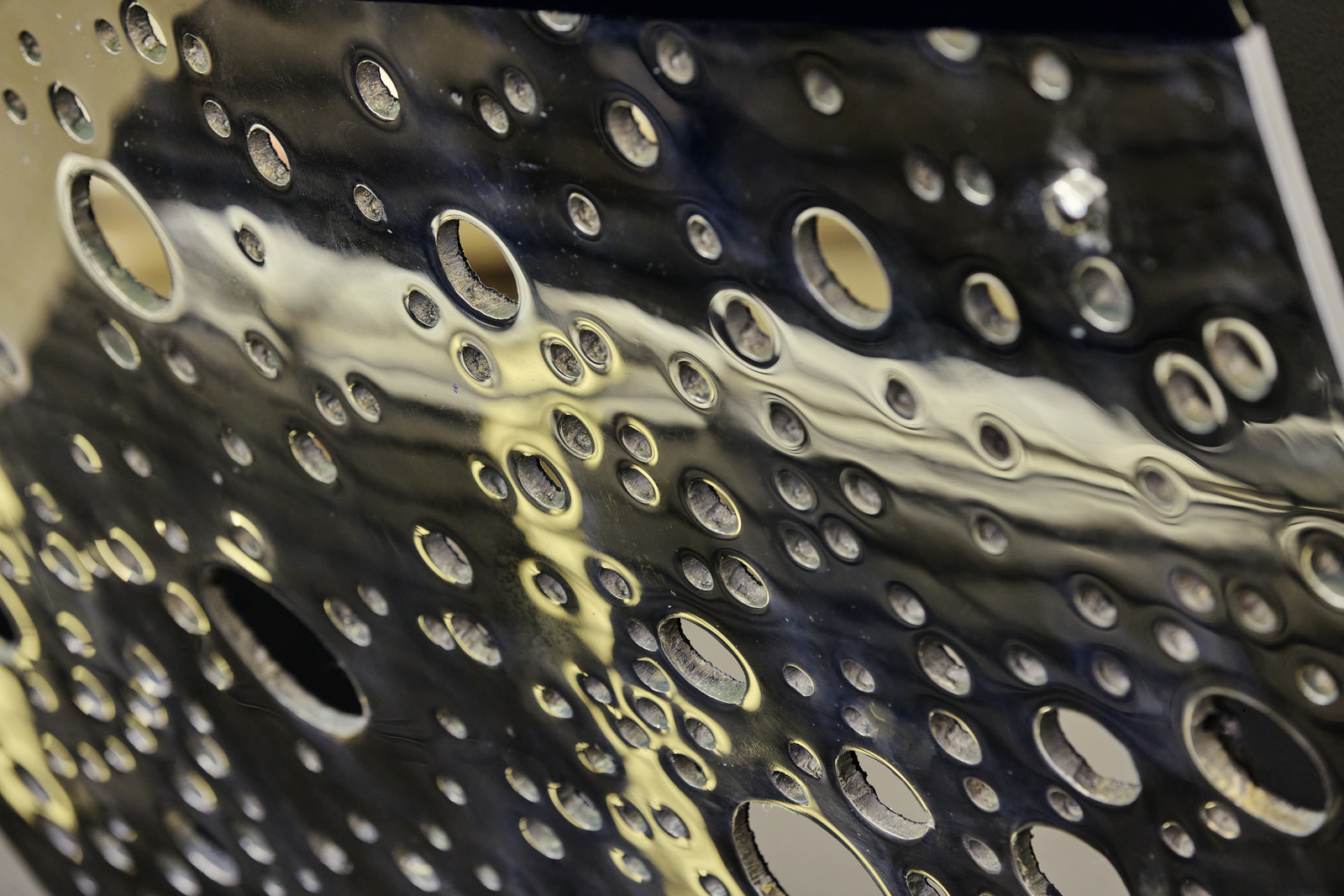

Ouroboros details at UAP Company, Brisbane, 2022. Images by Josef Ruckli

In welcoming LINDY LEE'S ambitious sculpture Ouroboros to the Gallery, DARLA TEJADA meditates on the significance of thresholds in Lee’s oeuvre.

Lindy Lee’s works are situated in sublime liminalities. From her distortion of family photographs to her monumental sculpture for the National Gallery of Australia, Ouroboros 2024, Lee’s artworks are inspired by and created from the tantalising tension of thresholds. Through the pervading perforations on the planes of her artworks, Lee demonstrates how the wholeness of being is experienced fully only at thresholds as they embody the two modes of living — movement and stillness.

Ouroboros itself occupies the very threshold of the National Gallery, placed at its main entrance in the Sculpture Garden. It is a fitting beacon, for like a threshold, Ouroboros is a static space witness to constant motion. Its surface of metal mirrors the shifting scenery of the life surrounding it. And just as it is witness to a changing landscape, those trapped in its polished planes view a moving environment when they lay eyes on the snake’s skin.

According to Lee, the creation of circles covering Ouroboros’s surface — the repetitive movement of their making — gave rise to a meditative state whose stillness allowed her ‘to be inside each moment of being’. For Lee, it was an experience of the infinitely unfolding present that exemplifies the never-ending cycle of movement and stillness. And this traversal from one state to another is a crossing of the thresholds that divide them. For just as thresholds are an inherent dichotomy — a fixed space of constant traversal — so too, as in Lee's work, do thresholds connect movement and stillness.

Ouroboros at UAP | Urban Art Projects, Brisbane, 2023, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, photo: Josef Ruckli

It comes as no surprise then that Lee incorporates her family portraits in her work, given the centrality of thresholds — and the infinite dichotomy of movement and stillness inherent in them — in her artistic practice. Photographs are an impassable window, yet they exist as one of a few examples of infinities. A written work must end when the mind and hand are exhausted. And barring replaying, a video or an audio recording only lasts for a finite period of time. But a photograph will endure ad infinitum. A captured moment that can last forever. To puncture holes with kisses of flames in these family photos borders on the profane. But maybe it is Lee’s desperate attempt to cross this immutable boundary. The forcing open of a permanently closed window.

For Lee, thresholds are also a conduit of flux. Ouroboros, through the holes cratering its skin, is ‘solidity dematerialising’. It is not static, ‘but rather one that is perpetually unfolding’.1 With its materiality evoking a dance ‘between something that is solid and something that is … drifting off to stardust’,2 Ouroboros is a sculpture evocative of action despite its fixed state. It is a snake perpetually eating itself, though never diminished. In its very name, movement — here the act of ‘eating’, the consumption of the self — is embedded. A still structure described by the motion of its eternal self-consumption, swallowing people in its metal maw.

The holes Lee created with flames in her family photos mirror the dark shame she felt about her identity, an illumination of her ancestry and a destruction giving way to renewal. Did the cleansing fire heal that pain in (her) genes? Surely those flames have cauterised her ‘sense of splitness’, irrevocably soldering her Chinese–Australian heritage. Here too, we see these burning thresholds give way for movement, for change.

Lindy Lee, The long road of the river of stars, 2015, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2018

Finally, a threshold’s most important function is to be a connection from place to place. And this ability to connect is central to Lee’s work. Ouroboros is a bridge between materiality and spirituality, a physical manifestation of the jewel nestled in each knot of Indra’s Net. Likening the universe to a net ‘at the ties of (which)... (can be found) a perfect and singular jewel’, the Buddhist philosophy of Indra's Net ‘is a parable that states that the primary cause of existence is profound interconnection’.3 During the day, it is a beacon of light, reflecting the sun’s rays. But the snake does not forget to reciprocate, giving back its own light to allay the dark night.

And perhaps Lee’s family photographs, riddled with holes, are a connection not only of land and of ancestry but also that of past, present and future. The plane of a photo is a place where the present can indefinitely interact with the past, where one has ‘invitation to deduction, speculation and fantasy’.4 For immigrants and diasporic communities, documentation is of utmost importance — there is the need to collate documents regarding the past in exchange for a new future in a new country. Are the holes in Lee’s pictures a way of creating space, a situating of herself within that history she used to shun?

For without rending holes, gaps, fissures and disjunctures on paper, wood or metal, there can be no openings. If thresholds would cease to exist, there would be no way in.

- Lindy Lee interviewed by Suhanya Raffel in ‘Between the Oceans of Birth and Death: An interview with Lindy Lee’, Lindy Lee: The dark of absolute freedom, learning resource, University of Queensland Art Museum, Brisbane, 2015.

- NGA media release, 23 September 2021. “National Gallery announces new Sculpture Garden commission by artist Lindy Lee”

- ‘Gulumbu Yunupiŋu Garak The Universe 2009’, The art that made me: Lindy Lee, Art Gallery of NSW

- Sontag, Susan (1977), ‘In Plato’s Cave’, On Photography (17), Penguin Classics

This story is part of the 2024 Young Writers Digital Residency.

Darla Tejada’s essay Art as movement building in solidarity with Palestine appears in Hyphen, Artlink’s Warltati / Summer issue 44:3, 2024. To find out more visit Artlink.