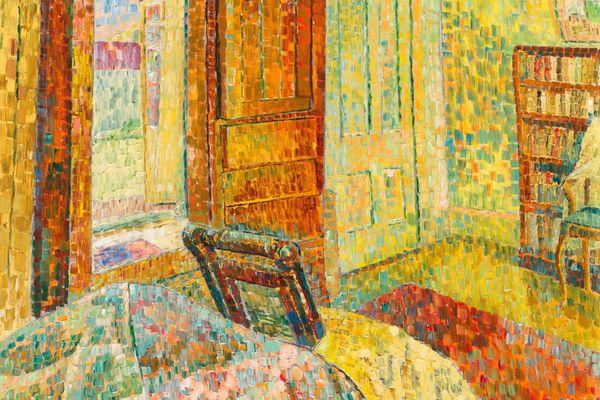

Andy Warhol

Biography

'Andy Warhol' 1986 gelatin silver photograph

Photography: Robert Mapplethorpe 1946-1989

© Robert Mapplethorpe Estate

Andrew Warhola, later known as Andy Warhol, was a key figure in Pop Art, an art movement which emerged in America and elsewhere in the 1950s and came to prominence over the next two decades. Drawing its subject matter from popular culture and often using mass production techniques, Pop Art was initially received with little enthusiasm by many in the art world. The noted American art critic Hilton Kramer, for example, was openly hostile in a Symposium on Pop Art held on 13 December 1962 at New York’s Museum of Modern Art: ‘Pop art does not tell us what it feels like to be living through the present moment of civilisation. Its social effect is simply to reconcile us to a world of commodities, banalities and vulgarities’, concluding that it was ‘indistinguishable from advertising art’. [1] At the same symposium, author and critic Dore Ashton lamented that ‘The artist is expected to cede to the choice of vulgar reality ...’, that Pop Art ‘shuns metaphor’ and that ‘far from being an art of social protest, it is an art of capitulation’. [2]

During the symposium discussions, which came to be rather heated, only Henry Geldzahler, Assistant Curator of American Painting and Sculpture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, felt able to embrace Pop Art as a legitimate movement. Geldzahler argued that, despite its obvious commercial origins, Pop was the art for the times:

Pop art was inevitable. The popular press, especially and most typically Life magazine, the movie close–up, black and white, technicolor and widescreen, the billboard extravaganzas and finally the introduction though television of this blatant appeal to our eye in the home – all this has made available to our society, and thus to the artist, an imagery so pervasive, persistent and compulsive that it had to be noticed. [3]

There could have been no more apt a subject for Geldzahler’s comments than Andy Warhol. Warhol took as themes everyday subject matter that resonated because of its familiar origins. Celebrities were a favourite – Marilyn Monroe, Elvis, Chairman Mao, Muhammad Ali and Mick Jagger all appeared and reappeared in his art. So too, the ever–present products in our daily lives, such as the humble can of Campbell’s Soup. On many occasions Warhol deliberately emphasised faulty or poor quality commercial printing, such as the slur of the ink through the screen or off–register colour. The repetitive nature of his compositions suggests an art of the assembly line. Warhol’s expressed ideal, in fact, was to make use of mass production techniques such as screenprinting for his canvases and prints. He established a large workshop on East 47th Street in New York in 1963. This new workshop was dubbed ‘the Factory’, which reiterated the artist’s intention to make an art that looked machine–made, produced in the manner of an assembly line. In 1967 ‘the Factory’ building was to be demolished and so Warhol moved his studio to 33 Union Square West and later in 1974 to 860 Broadway.

Warhol was born in Pittsburgh in the United States, in 1928, to parents of Carpatho–Rusyn descent. First his father before World War I, and later his mother, in the 1920s, emigrated there from a village in modern day Slovakia in the heart of mittel Europa. Warhol was brought up in impoverished circumstances. Despite this, his mother bought a film projector and the young Andy avidly watched cartoons. Bedridden for two months, he read comic books and magazines, cutting out his favourite imagery. It was this popular culture which formed the basis of Warhol’s childhood paintings and drawings. Warhol showed considerable talent in drawing as a school child and his art teacher recommended that he attend free art classes at the museum attached to the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh. From 1945 he continued studies at the Institute, majoring in painting and design, graduating in 1949. This institution based its curricula on ideas of practicality, somewhat akin to the German Bauhaus, combined with studies in the Fine Arts. At college Warhol was also taught commercial art techniques such as photo screenprinting – something he was later to incorporate into both his paintings and prints.

Warhol was ambitious from the start and, on completion of his studies in Pittsburgh, New York beckoned. He set off to make a name for himself with his college friend Philip Pearlstein who, like many at the Carnegie Institute, studied under a GI Bill after World War II. Warhol was among the youngest of the students at college. Over the next 10 years, he became a successful commercial artist in New York, working as an illustrator of magazines and books, a window dresser and a designer of advertisements, cleverly packaging his work and adding personal touches to please his growing clientele. Most successful were Warhol’s shoe advertisements for the company I. Miller and Sons. He developed a characteristic understated, quirky hand–drawn style, using a blotted–line technique. The artist would draw a composition in pencil and then trace the image in ink. While the ink was still wet he would blot it onto a Strathmore board. The board was hinged to the drawing in order that the inking could be carried out in stages so that it wouldn’t dry out. Using a monotype technique – that is, taking a once off image from a still wet master—Warhol then printed from the board. Should he wish to make multiple copies, he simply re–inked his drawing.

Andy Warhol’s near contemporaries Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns also worked as commercial artists under the joint alias ‘Matson John’ when decorating Tiffany windows or similar projects. Warhol, initially at least, had no qualms about being successful in the commercial world, working under his own name and accepting Art Director’s Awards in 1952, 1956 and 1957 and the American Institute of Graphic Art Award in 1954. Keen to have his art considered on its own terms, Warhol had two exhibitions of his drawings at the Bodley Gallery in New York in the mid 1950s. The first was of erotic male nudes, the next of golden slippers, richly ornate and embossed. One such drawing made at this time was the golden boot executed in gouache, gold paper and ink, now at the National Gallery of Australia. His openness about his work and success as a commercial artist was, however, later to haunt him. He found that many undervalued his attempts to become an artist in his own right. The stigma of being a commercial artist worked against him.

From 1960 Warhol began painting cartoon characters in a deadpan, banal manner, enlarging comic imagery and consumer products onto unstretched canvases using a projector. From these projections he usually painted directly onto the canvas or sometimes used photostats of the projections as the preliminary drawing. Initially, he had worked in a painterly manner. As his work evolved, however, Warhol wished to distance himself from his contemporaries. He openly rejected the methods of the Abstract Expressionists and sought to conceal any overtly gestural element—the human touch—in his art.

Five of his paintings were displayed in the windows of the department store Bonwit and Teller on Fifth Avenue and 57th Street in April of 1961. Desperate to be considered a legitimate artist, Warhol would frequent the New York galleries in the hope his own work might be accepted. On the advice of a friend who had recently seen Roy Lichtenstein’s painting, Warhol visited the Leo Castelli Gallery and was dismayed to see Lichtenstein’s comic strip subject matter—something Warhol himself had been painting. He had hoped that Castelli might add him to his stable of young artists working in New York, but nothing came of this due to the similarity of his own work with Lichtenstein’s and the fact that Castelli found Warhol’s work lifeless and cold.

Frustrated by this rejection (particularly as his cartoon paintings preceded Lichtenstein’s by about a year), a distraught Warhol then turned to Campbell’s Soup cans as a suitable subject for his art. This had been at the suggestion of the gallery owner, Muriel Latow, when Warhol lamented that ‘It’s too late for the cartoons. I’ve got to do something that will have a lot of impact, that will be different from Lichtenstein and Rosenquist.’ Warhol asked Latow what subject he should choose (as he often did with friends and colleagues) and she proposed that, along with money, Warhol should choose a subject ‘that everybody sees every day that everybody recognises … like a can of soup’. [4] So in late 1961 he began his images of Campbell’s Soup cans, sometimes as individual portraits and sometimes as group ‘sittings’. As before, he projected enlarged soup can images from photographs and then traced these in pencil onto the canvas. The soup can as a choice of subject astonished the art world. Warhol gained instant notoriety and an offer of an exhibition by the art dealer Irving Blum at his Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles. Warhol continued to develop this theme in his paintings and later in two series of prints produced during 1968 that featured different soup flavours.

Warhol had a fascination with things morbid. Sometimes, however, the results were astonishingly beautiful, such as the resonating, brilliantly coloured images of Marilyn Monroe. On the occasion of her suicide on August 1962 Warhol took a publicity shot by Gene Korman of Marilyn Monroe taken for the film Niagara made in 1953. Warhol cropped the 8" x 10" glossy to suit the proportion of the canvases he was using and screenprinted the composition for several paintings. The Marilyn canvases were early examples of Warhol’s use of screenprinting, a method the artist warmed to, recalling that:

In August ’62 I started doing silkscreens … I wanted something stronger that gave more of an assembly line effect. With silkscreening you pick a photograph, blow it up, transfer it in glue onto silk, and then roll ink across it so the ink goes through the silk but not through the glue. That way you get the same image, slightly different each time. It was all so simple – quick and chancy. I was thrilled with it. … When Marilyn Monroe happened to die that month, I got the idea to make screens of her beautiful face – the first Marilyns. [5]

Using photo–stencils in screenprinting meant that Warhol could use photographic images for his screenprints. The screen (originally silk, later other mesh fabrics) is covered with a photosensitive gelatine coating. Where light is projected though a negative transparency, the gelatine is hardened and this forms the stencil for printing, while the soft gelatine protected by the black of the negative areas is washed away with water. Different colour inks are then passed through the screen using a rubber blade called a squeegee.

At this time, Warhol was a proponent for using screenprinting in a non–commercial context. In an unfortunate echo of the Lichtenstein cartoon experience, after Warhol agreed to advise Rauschenberg on screenprinting, it was assumed in the art world that Warhol was the follower, not the precursor in adoption of this technique. In fact, the reverse was the case. Contributing to his constant sense of rejection as a legitimate artist, Warhol developed an ironic public persona of indifference and superficiality, claiming one needed to only look at the surface of his work: ‘If you want to know all about Andy Warhol … Just look at the surface of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There is nothing behind it.’ [6] Warhol also revelled in his apparent machine aesthetic, noting, ‘The things I want to show are mechanical. Machines have less problems. I’d like to be a machine, wouldn’t you?’ [7] Yet on some occasions the human element would ‘creep’ in, according to an assistant at the Factory, with ‘a smudge here, a bad silk screening there, an unintentional cropping’.[8] Later Warhol was to deliberately contradict his own pronouncements and introduce a painterly quality to his work, or purposely utilise off–register colours in the screenprinting process.

Warhol used the same images for his screenprint series of 10 works, Marilyn Monroe (Marilyn) published in 1967 by Factory Additions, a publishing arm Warhol established with art gallery dealer David Whitney. The series was produced in an edition of 250; the fabulous colours said to have been selected by Whitney. However, there were various other unauthorised editions made subsequently using the original matrix for the Marilyn screenprint series. For many of the later proofs (still not completely documented) each sheet on the verso bears the black stamp ‘Published by Sunday B Morning’ and ‘Fill in your signature’ denoting that others were pulling and printing the series at idle times. To complicate matters further, some proofs were also signed in hand by Warhol ‘This is not by me. Andy Warhol.’ In addition further proofs were run off without the artist’s knowledge and considered ‘fakes’ by the artist. [9]

At the suggestion of Geldzahler, who thought the artist should address tougher subjects, Warhol went on to pursue themes of death and disaster, frequently sourcing images from sensational tabloids or pulp magazines. He was attracted to the themes of car crashes, race riots and executions which, as images, appear in often macabre, trashy or banal formulations. These images of death and disaster retain an enigmatic lingering power. The Electric chair series of prints from 1971, for example, are derived from a photograph of the electric chair in Sing Sing Penitentiary in Ossining, New York, where the convicted Soviet spies Julius and Ethel Rosenberg had been executed on 13 January 1953 at the height of the Cold War. This was released by the press service Wide World Photo on the day of the execution. Warhol had first used this image in the painting Lavender disaster in 1963 – the year two other convicts were executed at the same prison. As with many of his subjects, Warhol later recycled his imagery. For the Electric chair print series of 1971, the artist cropped the photograph, honing in on the empty chair. Often using pastel decorator colours, applied in a painterly manner, the contrast between the deathly subject and the softened, almost delicate, technique underscores the horror of the execution chamber.

From 1963 Warhol pursued a career in 16mm filmmaking. He was almost a passive voyeur. Using a fixed camera and no editing, films such as Sleep, Blow Job, Eat, Haircut and Kiss were unconventional, often erotic, frequently chaotic, sometimes mesmerising and mind–numbing. While pursuing his filmmaking career in the late 1960s, Warhol spent some time filming in Los Angeles. It was during this time that he began working with John Coplans, Director of the Pasenda Art Museum, on exhibitions. Coplans was keen to develop a fundraising publication for the museum. To this end the director approached master printer Ken Tyler. The latter was keen to invite the best young artists around to make prints at his Gemini GEL workshop in Los Angeles in the late 1960s and early 1970s. One such artist was Andy Warhol. According to the printer:

Andy made some wonderful AB Dick Mimeograph hand–cut stencils in the early 60s for this project that never materialized. John Coplans thought I could transfer the stencils into lithography and print editions from them. I experimented with them and decided I would lose the stencils during the process and I wasn’t sure I could get great results. I had done some similar trials in 1968 for Oldenburg’s portfolio of Notes using mimeograph stencils. About the same time (1970) Andy had asked me to design a ‘floating card machine’ to show his portrait images in.

Sadly the Museum publication did not proceed. According to Tyler:

The project never developed into a prototype model and was abandoned. I kept trying to get Andy to print with me, but his deal with David Whitney & Company for publishing large screenprint editions with many undocumented proofs, prohibited me from working with him. There was a lot of art world politics and suspect dealings involved with Warhol and Company which I could never be a part of and I also was not in a position to financially compete.

No long–lasting collaboration with Warhol was possible for the printer. ‘The Warhol story is a brief one for me’, Tyler recently recalled. ‘We met in the late 60s through David Whitney, Irving Blum and Leo Castelli and saw each other at openings, etc. Getting to know Andy who was always surrounded by people who worked for him was difficult. Andy was polite, charming, complicated and very hard to figure out what he was thinking and often what he was saying.’

There was, however, one successful outcome for Tyler: ‘In 1972 the Vote McGovern campaign asked me to do a campaign print with Andy while he was filming in LA, which Andy agreed to, so the 16–colour screenprint was made. No more prints after that, even with Andy loving the print job that Jeff Wasserman, my screenprinter did.’ [10]

The idea for Vote McGovern had its origins in an earlier poster made by Ben Shahn, an artist whom Warhol greatly admired. In 1964 Shahn had designed a poster in support of the Democratic presidential candidate Lyndon Baines Johnson. For this work, over the caption ‘Vote Johnson’ Shahn had sketched a cartoon–like face of Republican candidate Barry Goldwater with large spectacles and a toothy grin. For his own foray into politics, Warhol took a photographic image of Richard Nixon, which had appeared as the cover for Newsweek on 27 January 1969. For this 16–colour screenprint, Warhol gave his Republican candidate a hideous green face with yellow lips and a blue five–o’clock shadow (something the politician was noted for in comparison with the photogenic John Kennedy). Underneath he placed the caption calling to vote for Democratic candidate McGovern. It was this foray into the political world that Warhol subsequently blamed for the constant scrutiny of his taxes by the Internal Revenue Service.

Always keen for new subject matter, developments in American foreign policy presented Warhol with a new celebrity. In 1972 President Nixon made his first official trip to China—a country that had been unrecognised by many in the West ever since the Communist Revolution of 1949. There Nixon met the Chinese Communist leader, Chairman Mao Zedong, heralding a new era of diplomacy. This event and the figure of Mao provided a new icon for the artist. Warhol took his image of Mao from the cover of the Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse–tung, produced in millions of copies. He created multiple versions of Mao screenprinted onto canvas of various sizes, which became increasingly painterly. This gestural quality was also evident in the 1972 print version of 10 works that feature hand–drawn marks around the head of Mao and unevenly inked colours.

By the 1970s Warhol no longer relied on found imagery and had considerably expanded his range of subjects. He often took his own photographs and the ‘hand–made’ element became increasingly evident by additions of collage elements using torn cheap graphic Color Aid papers, which were produced in a seemingly endless array of colours. The single portrait of Paloma Picasso published as part of the series of homage portfolios to honour her late father and the series of 10 screenprints of Mick Jagger were characteristic of this change in style. Warhol had met Jagger in 1963 when the band the Rolling Stones were not well known in the United States. Warhol had designed the band’s provocative album cover for Sticky fingers with its focus on a man’s crotch and a zipper that opened. The album and the design proved to be a huge success and Warhol, ever keen to make money, lamented that he had not been paid enough given the millions of copies that sold. No doubt with an eye for financial success, Warhol turned to the subject of Mick Jagger for a new print series. Although the rock star disliked Warhol’s voyeurism and in the early days the artist thought Jagger ‘awful looking’, he was now a celebrity friend and part of the New York club scene. Using a selection of 10 photographs he had taken of Jagger, Warhol produced a series of 10 screenprints, with a pronounced collage look and a suprisingly dark palette highlighted by occasional bright pinks and oranges.

Throughout his career Warhol relied on assistants to help produce his work, beginning with Nathan Gluck in the mid 1950s and continuing with Gerard Malanga and Jay Skinner. It was not until 1977 that he hired a printer for his publications. Rupert Smith continued to work for him until the time of Warhol’s death. [11] Greater care was now taken with the printing, and regular proofing of work took place (something Warhol had not done previously) to ensure a high quality. One print series made in this manner was the set of four screenprints of Muhammad Ali. Like Jagger he was a celebrity, but in a totally new field for Warhol—sport. Warhol took four of his own photographs of the handsome boxer. The collage look characteristic of the 70s is less random in this 1978 screenprint series, with colour highlighting certain aspects of his subject, such as his fist or a profile. Despite his protestations to the contrary—‘I don’t believe in style. I don’t want my art to have style’—Warhol’s art evolved stylistically over the 1960s and 1970s.

Years later, we see things differently in Warhol’s art—he has a distinct style and choice of subject matter that is unmistakably and singularly his own.

Jane Kinsman

Senior Curator

International Prints, Drawings & Illustrated Books

This text was prepared for the travelling exhibition Afterimage: Screenprints of Andy Warhol

[1] Hilton Kramer, quoted in a special supplement ‘A symposium on Pop Art’ Arts Magazine April 1963 pp.38–39. The symposium was held at the Museum of Modern Art on 13 December 1962 and was published in the following year, in its entirety pp.36–45.

[2] Dore Ashton, ibid. p.39.

[3] Henry Geldzahler, op. cit. p.37.

[4] Muriel Latow, quoted in Victor BockrisWarhol London: Frederick Muller 1989 p.143.

[5] Andy Warhol in Warhol and Pat Hackett (eds) POPism; the Warhol ‘60s New York and London: Harcourt, Brace Jovanovich 1980 p.22.

[6] Warhol in David Bailey Andy Warhol Transcript of Bailey’s ATV Documentary, London: Bailey, Litchfield/Mathews Miller Dunbar Ltd 1972 n.p. quoted in David Bourdon Warhol New York, Harry N Abrams Inc. 1989 p.10.

[7] Warhol quoted in David BourdonWarhol New York: Harry N Abrams., Inc. 1989 p 140.

[8] Gerard Malanga ‘A conversation with Andy Warhol’ Print Collector’s Newsletter vol.1 no.6 January–February 1971 p.125.

[9] For example, see Warhol’s diary entry for 1 December 1976 and the ‘fake’ Electric chairs, in Hackett (ed.) The Andy Warhol diaries, New York: Warner Books 1989 p.4.

[10] All quotes by Ken Tyler in correspondence with Jane Kinsman dated 21 May 2003.

[11] Marco Livingstone ‘Do it yourself: notes on Warhol’s techniques’ in Kynaston McShine (ed.) Andy Warhol: a retrospective New York: The Museum of Modern Art 1989 pp.63–78; ‘Rupert Jasen Smith on printmaking’ in Frayda Feldman and Jörg Schellmann (eds.) Andy Warhol Prints: a catalogue raisonné New York: Ronald Feldman Fine Arts Inc.; Munich/New York: Editions Schellmann; New York: Abbeville Press 1989 pp.25–27.

Works in the Kenneth E. Tyler Collection

Further Reading

EXHIBITION

- Lichtenstein to Warhol: The Kenneth Tyler Collection, 2019–20

- Andy and Oz, 2007

- After Image: Screenprints of Andy Warhol, 2003–04

- Pop! Prints from the 1960s and 1970s, 8 June 1991 – 24 May 1992

- The Artist as Social Critic, 10 May – 3 August 1986

NATIONAL GALLERY PUBLICATIONS

- Lichtenstein to Warhol: The Kenneth Tyler Collection, Jane Kinsman, exhibition catalogue, 2019

- Workshop: The Kenneth Tyler Collection, Jane Kinsman (ed.), 2015

RELATED LINKS