Emily Kam Kngwarray

Alhalkere, Paintings from Utopia

13 Feb – 18 Apr 1999

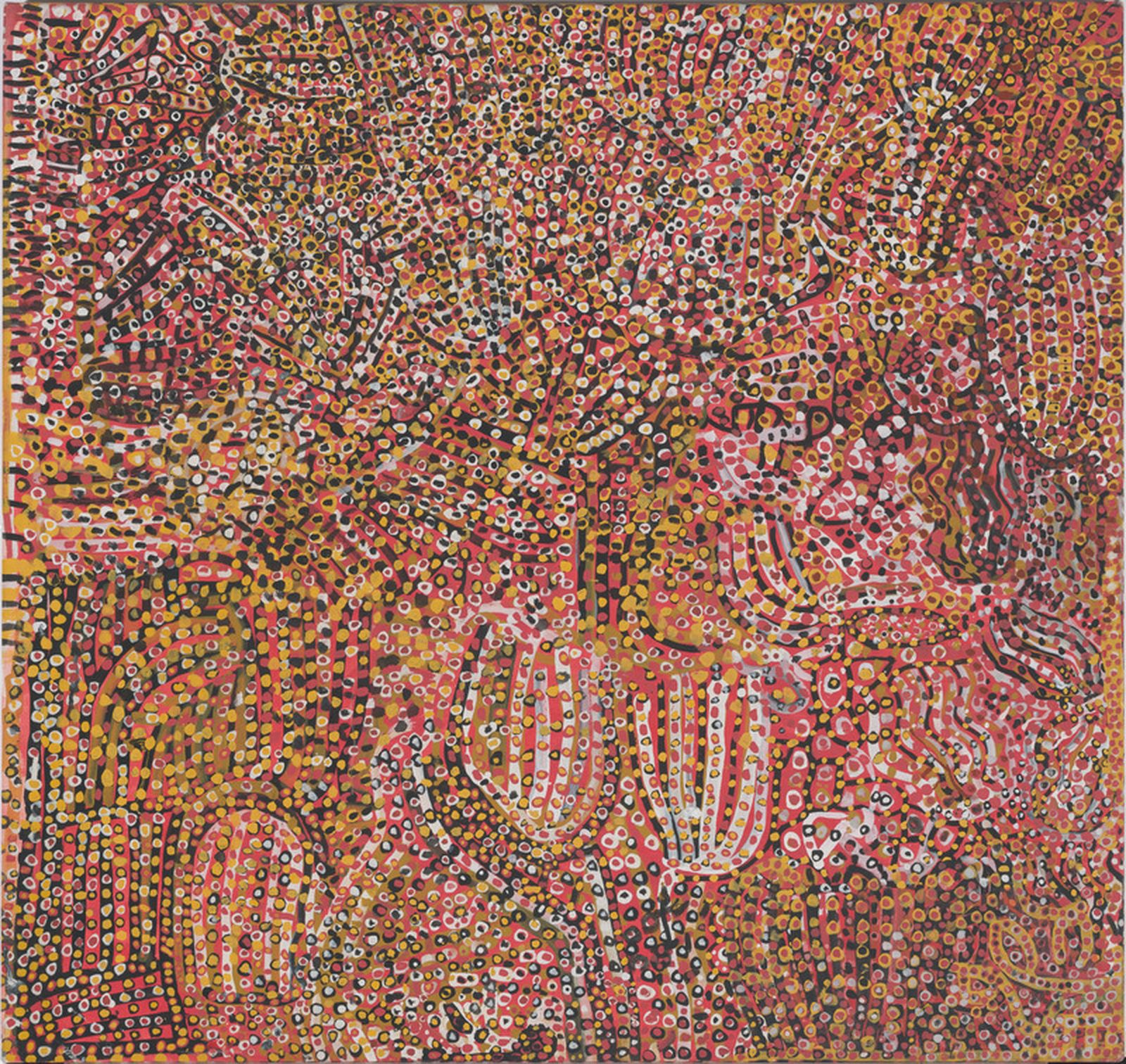

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Anmatyerr people, Ntang Dreaming, 1989, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1989 © Emily Kam Kngwarray/Copyright Agency

About

In the 1990s Emily Kam Kngwarray (c.1910–1996) emerged as one of Australia's leading painters of modern times. Kngwarreye's prominence is no overnight sensation; it finds its roots in a lifetime of ritual and artistic activity. Her energetic paintings are a response to the land of her birth, Alhalkere, north of Alice Springs—the contours of the landscape, the cycles of seasons, the parched land, the flow of flooding waters and sweeping rains, the patterns of seeds and the shape of plants, and the spiritual forces which imbue the country. Kngwarreye's vision of the land is unique; her paintings challenge the way we look at art by Aboriginal Australians. Emily Kam Kngwarray: Alhalkere—Paintings from Utopia traces the brief but impressive career of an artist who started painting in the public arena when she was in her eighties.

Kngwarreye was a founding member of the Utopia Women's Batik Group which commenced operations in 1977. This communal project operated on an egalitarian basis (on the traditional model). No one artist was singled out above the rest. All were encouraged equally to produce work. The Holmes à Court Collection sponsored a series of similar projects which launched the Utopia artists into the public domain on a scale they had not experienced previously. Through the use of introduced materials, their art had begun the transition from the private to the public domain.

Kngwarreye's painting began to attract attention partly due to the prominence gained by the reproduction of her first canvas, Emu woman 1988–89 on the cover of The Summer Project catalogue for the exhibition at the S.H. Ervin Gallery in Sydney in 1989. The work was selected as a mark of respect to the artist's seniority.1 Emu woman bears similarities in style to her early Awelye2 paintings; they possess strong linear structures upon which distinct individual dots straddle lines and overlap in the areas of ground.

In 1990 the egalitarian attitude fostered by CAAMA (Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association) was set aside for a joint artist-in-residence program and exhibition of the work of Kngwarreye and Louie Pwerle (born c.1938) at the Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts. That year Kngwarreye had her first solo exhibition at Utopia Art Sydney.3

Suddenly, public interest in Kngwarreye's paintings created a great demand. Within a short space of time her earnings were substantial but would be, according to custom, distributed amongst kin. From this grew a level of expectation and the pressure to produce work, from family members and dealers alike.4 Kngwarreye's attitude to the results of the growing popularity of her work, represented in cash and adulation, was very much based in traditional values and modes. For example, in 1992 she received an Australian Artist's Creative Fellowship, a substantial sum awarded to artists who have made a major contribution to the cultural heritage of the nation. Kngwarreye regarded the award as recognition of her past efforts and the means to retire; it was time to pass on the mantle of senior artist to others. The demands of the community and family were never to make this possible. She was the great provider.5

The notion of the star artist or the 'solitary genius'6 has been considered antithetical to indigenous custom. Tradition demands the reciprocal rights and obligations in all matters concerning the group or clan, whether it be in rights to land, performance of ceremony, songs, dances and stories, or ownership of painted designs and images. It may also permeate the group's activities in the public domain. Nonetheless, within the communal whole, each individual has an inherited place, one which is enhanced through ritual and through personal attainments. The notions of individual and group are therefore not necessarily mutually exclusive. Further, as in Kngwarreye's case, the benefit accrued by the individual is reflected in benefits to the group as a whole.

Kngwarreye was an eager participant in each of the communal Utopia projects, and it is the early batik work which holds the clues to her development as a painter. The technique of batik is unforgiving; each mark, each stroke of the canting is recorded, layer upon layer. None is obliterated.

An early batik, Length of fabric of 1981 holds some clues to Emily's range of imagery. The cloth is composed on a linear grid; in some cases dots are laid down in lines, either following a form or filling in a space within the grid. In places dots appear within others. Free-flowing lines and 'patches' of dotting complete the composition.

The work reveal's an exuberance of gesture and a sureness of hand. Here we find the elements which are to recur in Kngwarreye's later paintings; the grids which structure the pictures, the sequences of dots aligned against or over lines, the straight dashes or lines, the wandering lines of unpredictable but resolved logic, the areas of dotting and the build up of colour. These elements are reinterpreted, re-invented, used separately or in varying combinations, refreshed and revitalised in the paintings. The paintings, however, are constructed from a closed set of marks and images found in the batiks. There is no unilinear progression in the development in her painting, rather, Kngwarreye uses the lexicon of marks as a springboard, constantly varying, reinterpreting and creating anew with every touch of the brush to the canvas.

The paintings are not the daubings of an 'untutored' artist acting purely on intuition; the term has been applied often in the press to hype up the phenomenon which is Kngwarreye. Intuitive no doubt these works are; but it is an intuition founded on decades of making art for private purposes, of drawing in the soft earth, of painting on people's bodies in ritual or, in the late 1970s, of painting on the bodies of the Utopia women as they successfully presented their claims to their land in legal proceedings.

Wally Caruana

This text is based on an article written for the catalogue of the exhibition from the Holmes à Collection, Utopia: Ancient Cultures/New Forms, at Galerie Petronas, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 12 November – 10 December 1998. Reprinted with permission.

Education Resources

This survey exhibition pays tribute to Emily Kam Kngwarray, a traditional ceremonial artist from a remote desert community who emerged this decade as one of Australia’s great modern painters.

Kngwarray died on 2 September 1996. She was a senior member of the Anmatyerre clan, and a custodian of the Dreaming sites in Alhalkere, her paternal clan country in Utopia, a tract of land 250 kilometres north-east of Alice Springs. Kngwarray was about 70 when she began making art for public display, and she became prolific, producing an estimated 3000 works in eight years. But her spectacular public career was not an overnight phenomenon; it had its roots in a lifetime of making art for ceremonial and everyday purposes. Her batik and acrylic paintings reveal her proficiency as a major traditional artist and custodian of the country of her birth, Alhalkere.

This exhibition charts the evolution of Kngwarray’s short, intensive public career; from early batik works to her final 1996 canvases. Her relationship with the country is revealed as a constant thread connecting her first works with her last.

The artist’s life

Emily Kam Kngwarray was born early this century, probably around 1910. No specific date is known as Aboriginal births were not compulsorily recorded until the 1960s. She was born on the eastern edge of her father’s country, Alhalkere and grew up in the traditional Alhalkere way, absorbing the ‘spirit’ of the country. An important part of her education was learning awelye or women’s business, ceremonies associated with women’s social structure and ritual knowledge. Awelye also describes the painted designs and images associated with women’s rituals.

When Alhalkere and surrounding clan lands were annexed by pastoral leases during the 1920s, Kngwarray and her people were forced to work for pastoralists. She worked chiefly at Woodgreen Station looking after domestic animals, but also led camel trains and even worked at the Wolfram mine in return for rations.

As well as being a ceremonial leader, Kngwarray was active in the land rights movement. In 1979 she played an important role in the return of Utopia Station, a 2000 square kilometre cattle property, to her people, the traditional owners.

In 1977 Kngwarray, with some other women from Utopia, attended a bush workshop to learn about batik. This was her first experience with non-indigenous materials and techniques. The following year the women formed the Utopia Women’s Batik Group which became known for beautiful, fluid designs on silk. It was with this group that Kngwarray made her first trip to Adelaide in 1981, accompanying the exhibition Floating Forests of Silk. In 1988 Kngwarray had her first experience of painting in acrylics on canvas and she quickly adapted the techniques and iconography of batik to this new and more direct creative process.

Kngwarray first drew widespread attention when her acrylic paintings were displayed in Sydney in 1989. Soon after she was awarded a community based artist-in-residency project from the Robert Holmes à Court Foundation and the following year, 1990, her first commercial solo exhibition was mounted at Utopia Art, Sydney. In 1992 she was awarded the prestigious Australia Council’s Australian Artists Creative Fellowship and travelled to Canberra to receive the award. She visited the National Gallery of Australia on this occasion. Finally, after her death in 1996, Kngwarray’s work represented Australia at the 1997 Venice Biennale.

The artist’s inspiration

Emily Kam Kngwarray’s paintings are a response to the land and the spiritual forces which imbue it; the contours and formations of the landscape, climatic changes, the parched earth and flooding rains, the shapes and patterns of seeds and plants.

Awelye

Kngwarray first became a painter as a young woman embarking upon her ritual education. She learnt about awelye designs while painting on the bodies of women about to take part in a ceremony. Awelye refers to the ceremonial world of women, or women’s business, and includes women’s ceremonial body designs. It also might refer to a particular ceremony and the designs songs and dances associated with it. The striped design painted on the breasts and neckline of ceremonial dancers seems to be the inspirational starting point for many of Kngwarray’s paintings.

Ceremonial cycles are held for individual ancestors. In 1990 Kngwarray listed the following designs as those over which she had authority:

Arlatyeye (pencil yam); Arkerrthe (mountain devil lizard); Ntange (grass seed); Tingu (dingo pup); Ankerre (emu); Intekwe (plant that emus like); Antwerle (green bean) and Kame (yam seed). That’s what I paint; whole lot.

Only the component parts are listed, not the complex interrelationship between them. ‘Whole lot’, which alone can be experienced through her painting, is her entire body of knowledge communicated subconsciously through the interplay of line, colour, movement, space and light.

Alhalkere country

Alhalkere is the name of the country of Emily Kam Kngwarray’s father and grandfather. It gained its name from a rock formation of the same name, eroded away from the escarpment. Kngwarray painted Alhalkere from a ‘traditional’ perspective, surveying her landscape with a spiritual eye. Her role was to learn its ancient history and all its physical characteristics as well as the responsibilities associated with maintaining the continuity of the land. Alhalkere is the home to the Yam Dreaming site from which Kngwarray takes her bush name, Kame. Yam seed was therefore one of her most important Dreamings.

The linear appearance of plants and tracks from her country are another source of inspiration for both her earlier batik paintings and her acrylic paintings on canvas. From her earliest works to her final canvases there is a conceptual and a physical continuity. Kngwarray indicated that she was aware that her art dealt with transcendent realities as much as physical landscape realities. However whether her batiks and paintings carried elaborate encoded creation stories remains a mystery as she was remarkably and consistently silent when asked to talk about her art.

The evolving art of Emily Kam Kngwarray

Batik

For the first 11 or so years of her public artistic career, from 1977 until 1988, Emily Kam Kngwarray worked in the traditional Indonesian resist technique called batik. Introduced to the women of Utopia in the late 1970s as part of an adult education program, this collaborative and communal activity was immediately popular with Aboriginal women artists. It was low tech. and could be done outdoors. Generally the silk or cotton was stretched over the artist’s knees, the fluid wax heated in pots, pans and hubcaps over open fires.

From the beginning, Kngwarray’s work displayed a raw vigour and a sinuous energy, which made her work stand out from the others. Interconnecting and layered lines and dots, plant and other figurative forms and cell like structures, combined to display her control over the flowing wax and overlayed dyes.

These early works displayed a vocabulary of marks, dots, lines of dots, lines of different widths, interconnected and overlayed, which she developed and explored in her later acrylic paintings. In both media, wax and paint, Kngwarray’s iconography remained constant.

Acrylic painting

Her first painting in 1988 was called Emu Woman. It immediately attracted the attention of the commercial art world in an exhibition at the S.H Ervin Gallery in Sydney. The energetic, dynamic, overall design of dots along lighter lines on a dark background created a sensation and almost overnight Kngwarray was recognised as an artist to collect.

Kngwarray tended to paint in series of works of a similar style. After the Emu Woman style she commenced a series of paintings with surfaces densely packed with dots with more dots within them.

Another stylistic shift took place when she began to use large brushes. She worked faster and more loosely and on a larger scale. Sometimes she made lines from sequential dots ‘dragging’ the brush while she dotted; her upper body moving like that of a dancer. The lines themselves snaking across the canvas are reminiscent of the sinuous forms of yam tubers and plants.

During the early 1990s Kngwarray began to use larger canvases, brighter jewel-like colours, pinks, blues, reds. Dots become lines, blurring and overlapping in spatially complex compositions. Her first suite of paintings, 25 small canvases, hung together to create a massive explosion of colour, was created in 1992. The similar The Alhalkere suite in the collection of the National Gallery was painted in 1993. Full of light, bright pastel pink and blue colour, the lineal structure of her earlier work was obliterated entirely by lines and patches of merging dots.

At the beginning of 1994 Kngwarray developed a new direction in her work in which she used the lineal forms of body designs and scarification marks as the primary source for her paintings. She had used lines before and then gradually submerged them under skeins of dots. Now she presented the art world with simple, bold compositions of parallel lines in strong dark colours. The paintings in this exhibition reflect the journey of the line in her work. Horizontal, vertical, parallel, thin, thick, dark, light, smooth, jagged, centrifugal. The web-like traceries of the yam, some in black and white are masterpieces of strength and simplicity.

Finally in a burst of energy, her ‘scribble’ phase led to atmospheric paintings, where line and dot were replaced by patches and drifts of colour.

The linear markings of grasses, yams, roots and tracks form lines of continuity connecting Kngwarray’s last works with her first. First revealed as spidery linear clusters in the early batiks, lines re-emerge in her late works, shortly before her death, as rapid multicoloured scribbles. This visible continuum represents metaphorically the unity between skin and soil, people and country, a timeless connection between Emily Kam Kngwarray with her country Alhalkere.

The exhibition

The exhibition of 89 major works includes batiks, acrylic paintings on canvas and works of art on paper. Included are important works which signal a stylistic change of direction and others that provide important interconnections. Arranged chronologically and grouped stylistically, this exhibition enables the visitor to appreciate the subtle changes which took place over Emily Kam Kngwarray’s brief public artistic career.

Preparation and activities for primary school students

To better understand the context of Emily Kam Kngwarray’s work, have the students research and prepare posters on the central and western desert region and the people who live there. The posters might cover some of the following topics:

The environment

- Find a map of Australia showing the states and the Northern Territory. Mark in Darwin, the desert area, Alice Springs, and some of the major towns or communities near it including Utopia, Papunya, Yuendumu and Hermannsburg.

- Find pictures of the desert and describe the landforms, weather conditions, plants and animals.

The people

- When did European people first arrive in the area and what have they used the land for?

- How do the Aboriginal people in this area live today? Find out about the languages spoken, ceremonies, and the roles of men and women.

The art of the Aboriginal people

- What types of materials do artists of the central and western desert use? Are these different from the materials used by other Aboriginal communities, for example Arnhem Land?

- When and how was acrylic painting introduced to the desert communities?

- What is batik?

- Discuss the role of painting in Aboriginal communities. Look at the different forms of ceremonial art — body painting, sand drawings, etc — and at painting for public viewing.

Background on the art of Emily Kam Kngwarray

- Using the teacher’s notes, discuss the biography of the artist.

Further activities

- Students collect leaves, roots, seeds, flowers from the garden and use them to create a multi layered design. Use line only.

- Look at the layout of the school and surrounds. Students make a ‘map’ of the area, then paint an image which uses this map as an underlying structure.

- Students make drawings of the ingredients for a typical meal at home. Create a design using these shapes and textures. Wax resist (crayons or candles) might be used.

Preparation and activities for secondary school students

Using resources from the list at the end of these notes, as well as the school and local libraries and the internet, students could:

write a short biography of Emily Kam Kngwarray:

- write about the main inspirations for her work

- describe her environment and the connection she had with it

- find information about the location and environment of Utopia and the central and western desert generally

- research the land rights movement in this area, for example the return of Utopia Station to its traditional owners

- find information about Aboriginal artists of the central and western desert

- research the origins of the public art of the desert, and its growth in recognition in the Australian and international art worlds.

Further activities

Research

- How do you determine your ‘country’? Produce an illustrated description of your country.

- Research the methods of body decoration used by different cultures around the world (include your own local culture). Compare them with ceremonial body art from the desert.

Practical

- Paint a series of small works using the same subject matter. Change the size of brush or make your own brushes.

- Collect a variety of seeds and use them as a basis for an artwork. Use repetition and magnification.

- Find out about batik.

Resources

- Boulter, Michael, The Art of Utopia: A new direction in contemporary Aboriginal art, Sydney: Craftsman House, 1991.

- Brody, Anne Marie, Stories: Eleven Aboriginal artists, Sydney: Craftsman House, 1997.

- Brody, Anne Marie, Utopia: A picture story, Perth: Heytesbury Holdings Ltd, 1990.

- Caruana, Wally, Aboriginal Art, Thames and Hudson, 1993.

- Neale, Margo, Emily Kame Kngwarreye: Alhalkere — Paintings from Utopia, Melbourne: Queensland Art Gallery and Macmillan Publishers Australia Pty Ltd, 1998.

- Johnson, Vivien, Aboriginal Artists of the Western Desert, Sydney: Craftsman House, 1994.

The above education materials have been sourced from an archived version of the National Gallery website.