Know My Name: Australian Women Artists 1900 To Now

14 Nov 2020 – 9 May 2021 (part one)

12 Jun 2021 – 26 Jun 2022 (part two)

Anne Ferran, Scenes on the Death of Nature I , 1986, KODAK (Australasia) PTY LTD Fund 1987 © Anne Ferran/Copyright Agency

About

Know My Name: Australian Women Artists 1900 to Now showcases art made by women. Drawn from the National Gallery’s collection and loans from across Australia, it is one of the most comprehensive presentations of art by women assembled in this country to date.

Told in two parts, this exhibition tells a new story of Australian art. Looking at moments in which women created new forms of art and cultural commentary such as feminism, Know My Name highlights creative and intellectual relationships between artists across time.

Know My Name is not a complete account; instead, the exhibition proposes alternative histories, challenging stereotypes and highlighting the stories and achievements of all women artists.

Know My Name: Australian Women Artists 1900 to Now is part of a series of ongoing gender equity initiatives by the Gallery to increase the representation of all women in its artistic program, collection development and organisational structures.

Know My Name: Australian Women Artists 1900 to Now will continue its evolution as one of the most comprehensive exhibitions of art by women ever assembled in Australia.

Curators: Deborah Hart, Head Curator, Australian Art and Elspeth Pitt, Curator, Australian Art with Yvette Dal Pozzo, Assistant Curator, Australian Art. Contributions by Kelli Cole, Curator, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art, and Rebecca Edwards, Sid and Fiona Myer Curator Australian Art.

Lineages

Women’s portraits and self-portraits reflect different stories and artistic connections. Unique to the women who make them, shell necklaces by Lola Greeno and her daughters and nieces connect generations of women. Presented nearby are portrait miniatures on porcelain and ivory, a form of portraiture intended to be held in the hand or kept close to the body.

Other self-portraits show women following their creative paths with conviction in defiance of the considerable difficulties they faced to become recognised as artists. In the early twentieth century, artists including Agnes Goodsir and Bessie Davidson found support outside of Australia, particularly in France, where they were able to live in creative communities, free from expectations of marriage and other heterosexual norms.

From images of young women to those in older age, from artists born in this country to those who have travelled here from other countries, these portraits represent ways of remembering and recognising artists’ important contributions to our cultural life.

Installation view, Know My Name: Australian Women Artists 1900 to Now, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 2021

Installation view: Lineages

Esme Timbery, Bidjigal people, Shellworked slippers, 2008, Collection: Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney. Purchased with funds provided by the Coe and Mordant families 2008

Nell, self‑nature is subtle and mysterious – nun.sex.monk.rock, 2010, Purchased 2021

Installation view: Lineages

Installation view: Lineages Showcase includes: Bess Norriss Tait, Coralie, 1907–10, Collection: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Felton Bequest 1910 Bernice Edwell, Portrait of Ida Rentoul Outhwaite, 1917, Gift of Vanessa Martin and Stella Palmer 2015 Bernice Edwell, Dolores Davies, 1919, Collection: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Gift of Mrs Dolores Barber 1977 Valerie MacSween, Pakana people, Shell necklace, 1995, Purchased 1998 Lola Greeno, Pakana people, Shell necklace, 1995, Purchased 1998 Dulcie Greeno, Pakana people, Shell necklace, 1998, Purchased 1998 Corrie Fullard, Pakana people, Shell necklace, 2002, Purchased 2003

Tjanpi Desert Weavers

Seven Sisters

Tjanpi Desert Weavers is an award-winning, Indigenous governed and directed social enterprise located on the Ngaanyatjarra Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara (NPY) lands in Central Australia. For 25 years, the Anangu women artists of the Tjanpi Desert Weavers (Tjanpi meaning ‘wild grass’ in Pitjantjatjara language) have developed and mastered their skills, weaving baskets and creative collaborative fibre art installations. These whimsical works generate awareness and insight into culture and Country alongside their focus of creating income and employment for women on their homelands.

During March 2020, as the heat rose and the wind rolled over the sand dunes on NPY Country, Tjanpi Desert Weavers artists came together to create their most ambitious collaborative work to date, Kungkarangkalpa (Seven Sisters). Working side by side, the women artists drew on their experience and cultural knowledge to create seven woven figures representing the sisters and a large woven form with small lights above, referencing the Pleiades star cluster.

The Seven Sisters is an epic ancestral story that has an important underlying teaching element, reinforcing law and cultural structures.

Installation view: Seven sisters

Tjanpi Desert Weavers: Dorcas Tinnimai Bennett (Ngaanyatjarra people), Cynthia Nyungalya Burke (Ngaanyatjarra people), Roma Yanyakarri Butler (Ngaanyatjarra people), Judith Yinyika Chambers

(Ngaanyatjarra people), Chriselda Farmer (Pitjantjatjara people), Polly Pawuya Jackson

(Ngaanyatjarra people), Joyce James (Ngaanyatjarra and Pitjantjatjara people), Eunice Yunurupa Porter (Ngaanyatjarra people), Winifred Puntjina Reid (Ngaanyatjarra people), Rosalie Richards

(Ngaanyatjarra people), Delilah Shepherd (Ngaanyatjarra people), Erica Ikunga Shorty

(Ngaanyatjarra people), Dallas Smythe (Ngaanyatjarra people), Martha Yunurupa Ward

(Ngaanyatjarra people), Nancy Nangawarra Ward (Ngaanyatjarra people), Kungkarangkalpa (Seven Sisters), 2020, Commissioned by the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra 2020

Tjungkara Ken, Pitjantjatjara people, Seven Sisters, 2012, Purchased 2012

Topsy Tjulyata, Pitjantjatjara people, Kungkarangkalpa: Seven Sisters story, 1992, Purchased 1993

Installation view: Seven sisters

Ken Family Collaborative: Freda Brady (Pitjantjatjara people), Sandra Ken (Pitjantjatjara people), Tjungkara Ken (Pitjantjatjara people), Paniny Mick (Pitjantjatjara people), Maringka Tunkin (Pitjantjatjara people), Tingila Yaritji Young (Pitjantjatjara people), Seven Sisters, Purchased 2020

Ken Family Collaborative: Freda Brady (Pitjantjatjara people), Sandra Ken (Pitjantjatjara people), Tjungkara Ken (Pitjantjatjara people), Paniny Mick (Pitjantjatjara people), Maringka Tunkin (Pitjantjatjara people), Tingila Yaritji Young (Pitjantjatjara people), Kangkura-KangkuraKu Tjukurpa – A sister’s story, 2017, Collection: Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide. Acquisition through Tarnanthi: Festival of Contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art supported by BHP 2018

Judy Watson, Waanyi people, canyon, Purchased 2003

Center: Tjanpi Desert Weavers, Kungkarangkalpa (Seven Sisters), 2020, Commissioned by the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra 2020

Back left: Tjungkara Ken, Pitjantjatjara people, Seven Sisters, 2012, Purchased 2012

Tjanpi Desert Weavers:

Dorcas Tinnimai Bennett (Ngaanyatjarra people),

Cynthia Nyungalya Burke (Ngaanyatjarra people),

Roma Yanyakarri Butler (Ngaanyatjarra people),

Judith Yinyika Chambers (Ngaanyatjarra people),

Chriselda Farmer (Pitjantjatjara people),

Polly Pawuya Jackson (Ngaanyatjarra people),

Joyce James (Ngaanyatjarra and Pitjantjatjara people),

Eunice Yunurupa Porter (Ngaanyatjarra people),

Winifred Puntjina Reid (Ngaanyatjarra people),

Rosalie Richards (Ngaanyatjarra people),

Delilah Shepherd (Ngaanyatjarra people),

Erica Ikunga Shorty (Ngaanyatjarra people),

Dallas Smythe (Ngaanyatjarra people),

Martha Yunurupa Ward (Ngaanyatjarra people),

Nancy Nangawarra Ward (Ngaanyatjarra people).

Installation view: Seven sisters

Left: Ken Family Collaborative: Freda Brady (Pitjantjatjara people), Sandra Ken (Pitjantjatjara people), Tjungkara Ken (Pitjantjatjara people), Paniny Mick (Pitjantjatjara people), Maringka Tunkin (Pitjantjatjara people), Tingila Yaritji Young (Pitjantjatjara people), Seven Sisters, 2018, Purchased 2020.

Centre: Tjanpi Desert Weavers: Dorcas Tinnimai Bennett (Ngaanyatjarra people), Cynthia Nyungalya Burke (Ngaanyatjarra people), Roma Yanyakarri Butler (Ngaanyatjarra people), Judith Yinyika Chambers (Ngaanyatjarra people), Chriselda Farmer (Pitjantjatjara people), Polly Pawuya Jackson (Ngaanyatjarra people), Joyce James (Ngaanyatjarra and Pitjantjatjara people), Eunice Yunurupa Porter (Ngaanyatjarra people), Winifred Puntjina Reid (Ngaanyatjarra people), Rosalie Richards (Ngaanyatjarra people), Delilah Shepherd (Ngaanyatjarra people), Erica Ikunga Shorty (Ngaanyatjarra people), Dallas Smythe (Ngaanyatjarra people), Martha Yunurupa Ward (Ngaanyatjarra people), Nancy Nangawarra Ward (Ngaanyatjarra people), Kungkarangkalpa (Seven Sisters), 2020, Commissioned by the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra 2020.

Right: Topsy Tjulyata, Pitjantjatjara people, Kungkarangkalpa: Seven Sisters story, 1992, Purchased 1993.

Installation view: Seven sisters

Ken Family Collaborative: Freda Brady (Pitjantjatjara people), Sandra Ken (Pitjantjatjara people), Tjungkara Ken (Pitjantjatjara people), Paniny Mick (Pitjantjatjara people), Maringka Tunkin (Pitjantjatjara people), Tingila Yaritji Young (Pitjantjatjara people), Seven Sisters, Purchased 2020

Tjanpi Desert Weavers: Dorcas Tinnimai Bennett (Ngaanyatjarra people), Cynthia Nyungalya Burke (Ngaanyatjarra people), Roma Yanyakarri Butler (Ngaanyatjarra people), Judith Yinyika Chambers (Ngaanyatjarra people), Chriselda Farmer (Pitjantjatjara people), Polly Pawuya Jackson (Ngaanyatjarra people), Joyce James (Ngaanyatjarra and Pitjantjatjara people), Eunice Yunurupa Porter (Ngaanyatjarra people), Winifred Puntjina Reid (Ngaanyatjarra people), Rosalie Richards (Ngaanyatjarra people), Delilah Shepherd (Ngaanyatjarra people), Erica Ikunga Shorty (Ngaanyatjarra people), Dallas Smythe (Ngaanyatjarra people), Martha Yunurupa Ward (Ngaanyatjarra people), Nancy Nangawarra Ward (Ngaanyatjarra people), Kungkarangkalpa (Seven Sisters), 2020, Commissioned by the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra 2020

Topsy Tjulyata, Pitjantjatjara people, Kungkarangkalpa: Seven Sisters story, 1992, Purchased 1993

Installation view: Seven sisters

Tjanpi Desert Weavers: Dorcas Tinnimai Bennett (Ngaanyatjarra people), Cynthia Nyungalya Burke (Ngaanyatjarra people), Roma Yanyakarri Butler (Ngaanyatjarra people), Judith Yinyika Chambers (Ngaanyatjarra people), Chriselda Farmer (Pitjantjatjara people), Polly Pawuya Jackson (Ngaanyatjarra people), Joyce James (Ngaanyatjarra and Pitjantjatjara people), Eunice Yunurupa Porter (Ngaanyatjarra people), Winifred Puntjina Reid (Ngaanyatjarra people), Rosalie Richards (Ngaanyatjarra people), Delilah Shepherd (Ngaanyatjarra people), Erica Ikunga Shorty (Ngaanyatjarra people), Dallas Smythe (Ngaanyatjarra people), Martha Yunurupa Ward (Ngaanyatjarra people), Nancy Nangawarra Ward (Ngaanyatjarra people), Kungkarangkalpa (Seven Sisters), 2020, Commissioned by the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra 2020

Topsy Tjulyata, Pitjantjatjara people, Kungkarangkalpa: Seven Sisters story, 1992, Purchased 1993

Ken Family Collaborative: Freda Brady (Pitjantjatjara people), Sandra Ken (Pitjantjatjara people), Tjungkara Ken (Pitjantjatjara people), Paniny Mick (Pitjantjatjara people), Maringka Tunkin (Pitjantjatjara people), Tingila Yaritji Young (Pitjantjatjara people), Kangkura-KangkuraKu Tjukurpa – A sister’s story, 2017, Collection: Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide. Acquisition through Tarnanthi: Festival of Contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art supported by BHP 2018

Connection with Country

"Arts and Country and environment are all one".

In these two rooms, and across different media, artists show their connections with Country and their interest in the environment. Connections to land and Ancestors are embodied in paintings by Waanyi artist Judy Watson, Kayardild/Kaiadilt artist Mirdidingkingathi Juwarnda Sally Gabori and Gija Elder Queenie McKenzie.

Community also informs the batiks by women artists from Utopia in the Northern Territory including Jeanie Pwerle and Rosie Kngwarray who portray women’s stories and ceremony in flowing designs. Emily Kam Kngwarray, an elder of considerable standing in her community, made batiks before becoming a painter in her 80s. Portraying her home Alhalkere with plants like atnwelarr (pencil yam) in bloom, her work attracted great attention, and she represented Australia posthumously at the Venice Biennale in 1997.

Rosalie Gascoigne and Fiona Hall were also selected for the Venice Biennale in 1982 and 2015 respectively. In the case of Gascoigne, her work was both closely connected with her experience of the region in which she lived and worked and resonant with broader international movements of land art. With Gascoigne and Hall, Janet Laurence is also an advocate for the preservation of the environment, as revealed in her installation, Requiem.

Installation view: Connection with Country

Janet Laurence, Requiem, 2020, Purchased 2021

Installation view: Connection with Country

Noŋgirrŋa Marawili, Maḏarrpa people, Baratjala, 2016, Purchased 2017. Supported by Wesfarmers Arts in recognition of the 50th Anniversary of the 1967 Referendum; Baratjala, 2016, Purchased 2017. Supported by Wesfarmers Arts in recognition of the 50th Anniversary of the 1967 Referendum

Mavis Warrngilna Ganambarr, Datiwuy people, Pandanus woven mat, 2008, Purchased 2013

Bronwyn Oliver, Trace, 2001, Purchased 2002; Garland, 2006, Purchased 2008

Bea Maddock, Terra Spiritus...with a darker shade of pale, 1993–98, Gordon Darling Australia Pacific Print Fund 1998

Rosalie Gascoigne, Feathered fence, 1979, Gift of the artist 1994

Installation view: Connection with Country

Mirdidingkingathi Juwarnda Sally Gabori, Kayardild/Kaiadilt people, Outside Dibirdibi, 2008, Acquired with the Founding Donors Fund 2009

Installation view: Connection with Country

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Anmatyerre people, Untitled (Alhalker), 1992, Collection: Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney. Mollie Gowing Acquisition Fund for Contemporary Aboriginal Art

Rosalie Gascoigne, Feathered fence, 1979, Gift of the artist 1994

Installation view, Know My Name: Australian Women Artists 1900 to Now, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 2021

Installation view: Connection with Country

Janet Laurence, Requiem (detail), 2020, Purchased 2021.

Installation view: Connection with Country

Dr B. Marika, Rirratjiŋu people, Yalaŋbara, 1988, Commissioned by the National Gallery of Australia and the Australian Bicentennial Authority 1988; Miyapunu and guya, Purchased 1987; Muka milny mirri, 1987, Purchased from Gallery admission charges 1988; Birds and fishes, 1984, Gift of Theo Tremblay 1987; Miyapunawu narrunan (Turtle hunting Bremer Island), 1989, Gift of the artist 1990

Queenie McKenzie, Gija people, Gija Country, 1995, Purchased 1996

Collaboration and care

The creation of community spaces in the latter part of the twentieth century expanded the places – such as schools and private studios – in which art had typically been made. In addition to childcare services and respite from domestic violence, dedicated women’s spaces, including the South Sydney Women’s Centre, offered screen-printing classes. The resulting posters spoke to a range of women’s and broader issues including Aboriginal land rights and environmentalism. As the feminist artist and activist Ann Newmarch observed, these kinds of works were ‘not intended for an elite “educated” art gallery audience… but [as] a means of expression and communication…’.

A pioneer of community-based art in Australia, Vivienne Binns made Tower of Babel with colleagues, friends and family members whom she described as her ‘personal community of influence, respect and care’. She states that her work is a ‘way to understand art as a human activity rather than something that only Artists do.’ This idea is also expressed in the Westbury quilt, the earliest work in the exhibition. Made by women members of the Hampson family, their lively quilt reflects the nature of their lives at the turn of the last century.

Installation view: Collaboration and care

Marie McMahon, You are on Aboriginal land, 1986, Gift of Daphne Morgan 2005.

Jan MacKay, Don’t be too polite girls, 1976, Purchased 1982.

Alice Hinton-Bateup, Kamilaroi/Wonnarua peoples, Ruth’s story, 1988, Gift of Marla Guppy 2019.

Frances (Budden) Phoenix, Relic (Mary’s blood never failed me), 1976 – 1977, Purchase 1994, Gift of Louise Dauth 2005.ff our bodies, 1980, Purchased 2019; No goddesses, no mistresses (Anarchofeminism), 1978, Purchased 2019.

Ann Newmarch, Women hold up half the sky!, 1978, Gift of the artist 1988; For Pammie, 1994, Gift of Louise Dauth 2005

Installation view: Collaboration and care

Misses Hampson, The Westbury quilt, 1900 – 1903, Purchased through the Australian Textiles Fund 1990

Installation view: Collaboration and care

Bonita Ely, Murray River punch, 1980, Courtesy of Bonita Ely and Milani Gallery, Brisbane

Jill Orr, Naomi Herzog (photographer), Southern cross – to bear and behold (flame); Southern cross – to bear and behold (burning), 2009, Courtesy of a private collection

Installation view: Collaboration and care

Jo Lloyd, Performers: Deanne Butterworth, Rebecca Jensen, Jo Lloyd; Producer: Michaela Coventry; Composer: Duane Morrison; Costumes: Andrew Treloar, Archive the archive, 2020, Performance commission generously supported by Philip Keir and Sarah Benjamin

Vivienne Binns with collaborators Daphne Anderson, John Abery, Genara Banzon, Lionel Bawden, Ray Beckett, Peter Binns, Beverley Bisset, Elsie Brown, Mike Brown, Erica Burgess, Norma Cairns, Eugene Carchesio, Cheo Chai-Hiang, Virginia Coventry, Rebecca Cummins, Mandhira De Saram, Bryan Doherty, Kate Dugdale, Lois Eastwood, Helen Eager, Bonita Ely, Nola Farman, Ruth Frost, Akira Fujishita, Kunio Fukushima, Tamio Fukushima, Mez Gates, Laurel Grey, Christopher Hodges, Pat Hoffie, Tess Horwitz, Kyomi Ititani, Hiroo Itoh, Josephine Knight, Shoichi Kogure, Steven Holland, Marie Howard, Wayne Hutchins, Narelle Jubelin, Therese Kenyon, Leonie Lane, Lila McLain, Marie McMahon, Seiko Machida, Irene Maher, Maria-Luisa Marino, David Martin, Eichi Matsuda, Jean Nixon, Rod O’Brien, Valerie Odewahn, Pat Parker, Elwyn Perkins, Gregory Pryor, Emily Purser, Neil Roberts, Catherine Rogers, Shigeyoshi Satoh, Dalia Shelef, Muriel Smith, Jane Stewart, Osami Tominaga, Peter Tully, Ruth Waller, Meg Walsh, Paul Westbury, Anthea Williams, Alice Whish, Tower of Babel, 1989 – continuing, Gift of the artist 2020

r e a, Gamilaraay/Wailwan/Biripi people, Resistance (flag), 1996, Purchased 2004

Installation view: Collaboration and care

Raquel Ormella, Australia rising #2, 2009, Purchased 2010.

Vivienne Binns with collaborators Daphne Anderson, John Abery, Genara Banzon, Lionel Bawden, Ray Beckett, Peter Binns, Beverley Bisset, Elsie Brown, Mike Brown, Erica Burgess, Norma Cairns, Eugene Carchesio, Cheo Chai-Hiang, Virginia Coventry, Rebecca Cummins, Mandhira De Saram, Bryan Doherty, Kate Dugdale, Lois Eastwood, Helen Eager, Bonita Ely, Nola Farman, Ruth Frost, Akira Fujishita, Kunio Fukushima, Tamio Fukushima, Mez Gates, Laurel Grey, Christopher Hodges, Pat Hoffie, Tess Horwitz, Kyomi Ititani, Hiroo Itoh, Josephine Knight, Shoichi Kogure, Steven Holland, Marie Howard, Wayne Hutchins, Narelle Jubelin, Therese Kenyon, Leonie Lane, Lila McLain, Marie McMahon, Seiko Machida, Irene Maher, Maria-Luisa Marino, David Martin, Eichi Matsuda, Jean Nixon, Rod O’Brien, Valerie Odewahn, Pat Parker, Elwyn Perkins, Gregory Pryor, Emily Purser, Neil Roberts, Catherine Rogers, Shigeyoshi Satoh, Dalia Shelef, Muriel Smith, Jane Stewart, Osami Tominaga, Peter Tully, Ruth Waller, Meg Walsh, Paul Westbury, Anthea Williams, Alice Whish, Tower of Babel, 1989 – continuing, Gift of the artist 2020.

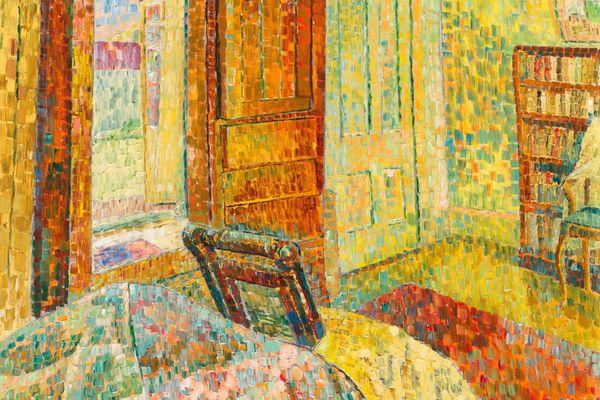

Colour, Light and Abstaction

It was largely women artists who first championed modernism and abstraction in Australia in the early twentieth century. Colour was key, and its formal and emotional qualities were used to create art that favoured idea and feeling above literal depiction.

In Beatrice Irwin’s book, The new science of colour, colour is described as ‘the very song of life and the spiritual speech of every living thing.’ Inspired by these observations, Grace Cossington Smith became known for the luminous and energetic surfaces of her paintings. While softer in tone, Clarice Beckett’s work looked at phenomena such as the flare of colour at sunrise and sunset. Her work is echoed in that of contemporary painter Gemma Smith, who describes colour as ‘magical’ in its ability to transform.

A tendency to focus on experiences of colour gradually paved the way towards pure abstraction. Artist Janet Dawson observed that ‘abstract work is a great joy … If you can empty your mind of chatter, and just live with the work for a few minutes, you find this enormous release into a mode of thought that is beyond speech.’

Installation view: Colour, light and abstraction

Anne Dangar, Plate, c 1935, Gift of Ruth Ainsworth 1998; Plate, c 1932, Gift of Grace Buckley in memory of Grace Crowley 1982; Plate, c 1935, Bequest of Michael Fizelle 1985; Plate, c 1937, Purchased 1978

Installation view: Colour, light and abstraction

Dorrit Black, The olive plantation, 1946, Collection: Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide. Bequest of the artist 1951

Grace Cossington Smith, The Bridge in building, 1929, Gift of Ellen Waugh 2005

Dorrit Black, The bridge, 1930, Collection: Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide. Bequest of the artist 1951

Grace Cossington Smith, The Lacquer Room, 1935–36, Collection: Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney. Purchased from the artist

Klytie Pate, High diving, c 1950, Purchased 1981

Ethel Carrick, At sunset, 1914, Purchased 1977

Hilda Rix Nicholas, Seller of earthenware pots, 1912-14, Purchased through the National Gallery of Australia Foundation Gala Dinner Fund 2013; Apples, c 1940, Purchased 2013

Ethel Carrick, The market, 1919, Private collection, courtesy of Smith & Singer, Melbourne and Sydney

Installation view: Colour, light and abstraction

Melinda Harper, Untitled, 2001, Purchased 2001

Savanhdary Vongpoothorn, Various levels, 2002, Purchased 2002

Carol Rudyard, Northern theme, 1973, Purchased 2005

Margaret Worth, Sukhāvati number 5, 1967, Gift of an anonymous donor 2020. Donated through the Australian Government's Cultural Gifts Program

Janet Dawson, Heeney's rose, 1968, Gift of Peggy Fauser 1976

Miriam Stannage, Aurora, 1970, Gift of the Stannage family 2019. Donated through the Australian Government's Cultural Gifts Program

Mira Gojak, Transfer station 1, 2011, Purchased 2021

Installation view: Colour, light and abstraction

Lesley Dumbrell, Foehn, 1975, Purchased 1976

Virginia Cuppaidge, Lyon, 1972, Gift of the artist 2012

Mira Gojak, Transfer station 1 (detail), 2011, Purchased 2021

Installation view: Colour, light and abstraction

Gemma Smith, Cusp, 2019, Courtesy of Gemma Smith and Sarah Cottier Gallery, Sydney

Mary Webb, Joie de vivre, 1958, Collection: Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney. Purchased 2011

Installation view: Colour, light and abstraction

Gemma Smith, Cusp, 2019, Courtesy of Gemma Smith and Sarah Cottier Gallery, Sydney

Mary Webb, Joie de vivre, 1958, Collection: Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney. Purchased 2011

Anne Dangar, Plate, c 1935, Gift of Ruth Ainsworth 1998; Plate, c 1932, Gift of Grace Buckley in memory of Grace Crowley 1982; Plate, c 1935, Bequest of Michael Fizelle 1985; Plate, c 1937, Purchased 1978

Grace Crowley, Abstract, 1953, Collection: Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney. Bequest of the artist 1980; Painting, 1951, Purchased 1969; Abstract painting, 1947, Purchased 1959; Abstract painting, 1952, Purchased 1976

Installation view: Colour, light and abstraction

Carol Rudyard, Northern theme, 1973, Purchased 2005

Mira Gojak, Transfer station 1 (detail), 2011, Purchased 2021

Performing gender

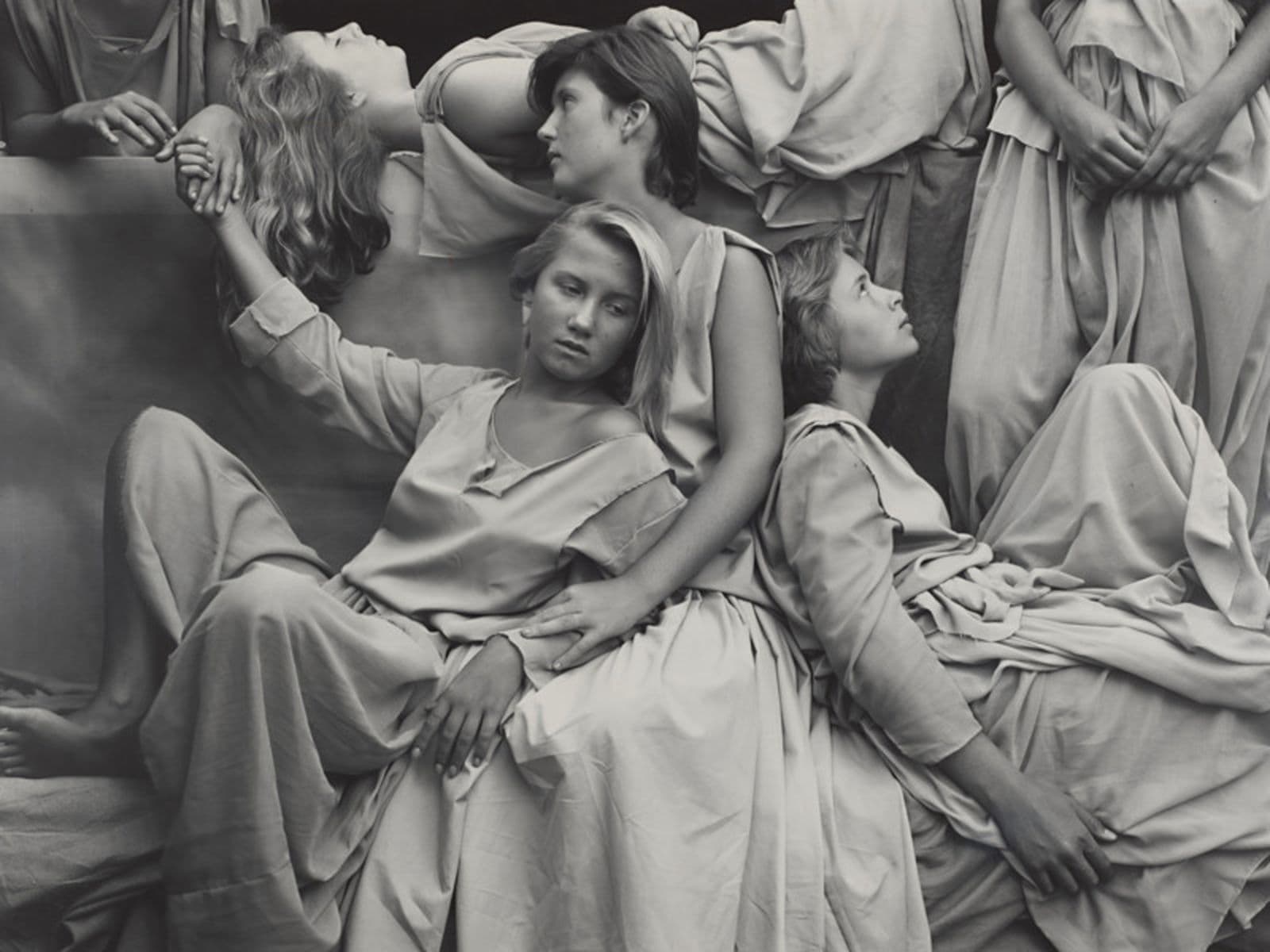

In the 1980s artists including Tracey Moffatt, Julie Rrap and Anne Ferran examined ideas of gender in works that merged photography and performance. In Scenes on the death of nature, Ferran used the camera to explore the pleasure and ethics of looking. Photographing a group of young women whose poses echo the forms of classical sculpture, Ferran considers the ways in which historical and contemporary images have positioned women as passive objects and sensual subjects.

Julie Rrap also explored the roles assigned to women in art in her series Persona and shadow. Inserting herself into paintings by the Norwegian artist Edvard Munch, Rrap twists her body to fit their original poses or, plays up or acts out in their limiting structures.

A lesser-known artist who worked earlier in the century, Janet Cumbrae Stewart’s paintings adopted the language of the academic nude. Celebrating her subjects, Cumbrae Stewart delighted in the acts of their dressing and undressing. While her work has been contested, with some criticising her use of a ‘male’ style, others admired her pioneering expression of desire and love between women.

Installation view: Performing gender

Tracey Moffatt, Something more, 1989, Courtesy of Naomi Milgrom AO, Melbourne.

Sanné Mestrom, Me & you, 2018, Purchased 2019.

Barbara Tribe, Lovers II, 1936–37 (cast 1988), Gift of the Barbara Tribe Foundation 2008.

Rosemary Madigan, Torso, 1948, Purchased 1976.

Installation view: Performing gender

Rosemary Madigan, Torso, 1948, Purchased 1976.

Freda Robertshaw, Standing nude, 1944,Collection: Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art, University of Western Australia, Perth.

Stella Bowen, Reclining nude, 1927, Collection: Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide. Gift of Mrs Suzanne Brookman through the Art Gallery of South Australia Foundation 2003.

Janet Cumbrae Stewart, The model disrobing, 1917,Collection: Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney. Purchased 1918.

Elise Blumann, Summer nude, 1939, Collection: University of Western Australia, Perth. Acquired with the assistance of the Visual Arts Board of the Australia Council and the Dr Albert Gild Fund 1976.

Installation view: Performing gender

Anne Ferran, Scenes on the death of nature I–V, 1986, KODAK (Australasia) PTY LTD Fund 1987; Purchased 2019

Installation view: Performing gender

Tracey Moffatt, Something more, 1989, Courtesy of Naomi Milgrom AO, Melbourne.

Rosemary Madigan, Torso, 1948, Purchased 1976.

Sanné Mestrom, Me & you, 2018, Purchased 2019.

Barbara Tribe, Lovers II, 1936–37 (cast 1988), Gift of the Barbara Tribe Foundation 2008.

Installation view: Performing gender

Tracey Moffatt, Something more, 1989, Courtesy of Naomi Milgrom AO, Melbourne

Installation view: Performing gender

Sanné Mestrom, Me & you (detail), 2018, Purchased 2019.

Anne Ferran, Scenes on the death of nature I–V (detail), 1986, KODAK (Australasia) PTY LTD Fund 1987; Purchased 2019.

Remembering

Memory, and the act of remembering, inform each of the works in this space. Kathy Temin’s memorial gardens challenge the idea of monuments as heroic sculptures cast in steel. Recalling the loss of family, Temin connects architectural forms and tenderness with the act of remembering, her faux-fur works reminiscent of childhood toys, soft to the touch and comforting.

The combination of meditative states and expressive gestures underpins Lindy’s Lee’s wall sculpture, The unconditioned. Based on the ancient art of Chinese flung ink painting, fragments of bronze form a mandala, or a chart of the cosmos, signifying the continuing cycles of life and death.

Activating memory through the body is implicit in Barbara Campbell’s Dubious letter, which was used in a performance work called Cries from the tower. The performance involved Campbell unravelling an embroidered skirt from a great height. For the artist, the falling ribbon symbolises the promise of escape and overlaps with histories of women held captive in fairy stories, poetry, literature and history alike.

Installation view: Remembering

Rosemary Laing, flight research #2a, #2b, #3, #4, #8 1999–2000; bulletproofglass #2, #3, 2002, Courtesy of Rosemary Laing; Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne; Stephen Grant and Bridget Pirrie; and Anthony Medich.

Lynda Draper, Black widow, 2019, The Sid and Fiona Myer Family Foundation Fund 2019.

eX de Medici, The wreckers, 2018–19, Purchased 2020

Installation view: Remembering

Del Kathryn Barton, the infinite adjustment of the throat…and then, a smile, 2019, Courtesy of Del Kathryn Barton and Roslyn Oxley9, Sydney.

Julie Rrap, Persona and shadow: Puberty; Sister; Senex; Conception; Siren; Christ; Madonna; Pieta; Virago, 1984, KODAK (Australasia) PTY LTD Fund 1984; Purchased 2019.

Rosemary Madigan, Torso, 1948, Purchased 1976.

Sanné Mestrom, Me & you, 2018, Purchased 2019.

Barbara Tribe, Lovers II, 1936–37 (cast 1988), Gift of the Barbara Tribe Foundation 2008.

Tracey Moffatt, Something more, 1989, Courtesy of Naomi Milgrom AO, Melbourne.

Installation view: Remembering

Kathy Temin, Pavilion garden, 2012, Purchased 2017.

Kathy Temin, Tombstone garden, 2012, Purchased 2012.

Marie Hagerty, deposition, 2012, Purchased 2013.

Installation view: Remembering

Barbara Campbell, Dubious letter from the performance Cries from the tower, 1992, Purchased 1995.

Jenny Watson, Self portrait as a narcotic, 1989, Collection: Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney. Purchased 1989.

Installation view: Remembering

Kathy Temin, Pavilion garden, 2012, Purchased 2017

Kathy Temin, Tombstone garden, 2012, Purchased 2012

Marie Hagerty, deposition (detail), 2012, Purchased 2013

Lindy Lee, The Unconditioned (detail), 2020, Courtesy of Lindy Lee and Sullivan+Strumpf, Sydney

Installation view: Remembering

Lindy Lee, The Unconditioned, 2020, Courtesy of Lindy Lee and Sullivan+Strumpf, Sydney

Micky's Room

Micky Allan’s first solo exhibition Photography, drawing, poetry: A live-in show was held at the Ewing and George Paton Galleries in Melbourne in 1978. She transformed the gallery into a domestic setting, installing her photographs, drawings, paintings, and poetry. Blurring private and public space, she ‘wanted to change the experience of the gallery goer from one of white walls, hush, hush, don’t speak, say what you really think when you get out of here’ to one that they could experience in a ‘combined rhythm’ with everyday life. Visitors of all ages participated in Allan’s exhibition, preparing snacks, watching TV, and lounging on the bed.

This room, developed in collaboration with the artist, is imagined in the spirit of her exhibition. It includes Allan’s art, personal tokens, and objects from her home, alongside the work and performance films of fellow artists from the 1970s to the present day.

Installation view: Micky’s Room

Installation view: Micky's Room

Carol Jerrems, selected works from A book about Australian women 1973–74, Published by Outback Press, Narrm/Melbourne, 1974 , selected works from the Gift of Mrs Joy Jerrems 1981; Gift of the Philip Morris Arts Grant 1982

Installation view: Micky’s Room

Margaret Dodd, This woman is not a car, 1982, Courtesy of Margaret Dodd.

Ruth Maddison, Lola McHaig, 60, Peg Fitzgerald, 64, Laura Thompson, 80, Pat Counihan, 74, Rose Stone, 69, Molly O’Sullivan, 83, from series Women over sixty, 1992, Kodak (Australasia) Pty Ltd Fund.

Installation view: Micky’s Room

Micky Allan, selected panels from The pavilion of death, dreams and desire: The family room, 1982, Purchased 1984.

Installation view: Micky’s Room

Jenny Christmann, 20 woollen books (detail), 1977–78, Gift of the Philip Morris Arts Grant 1982.

Isabel Davies, Kitchen creation (detail), 1977, Collection: Mildura Arts Centre, Victoria.

Framed photograph of Sue Ford and Micky Allan, framed photograph of Micky Allan’s 1978 performance exhibition Photography, Drawing, Poetry: A Live-in Show, books and objects all loaned from Micky Allan as part of the installation Micky’s Room 2020–2021.

Gemma Smith

Gemma Smith is a passionate researcher of colour, using her work to explore its subtleties and behaviours. She has remarked: ‘colour and its interactions have become the content of my work. There are so many possibilities to play out’. Recently working at the palest ends of the spectrum, Smith has collaborated with the curators of this exhibition, selecting colours for the walls that delicately shift from room to room, appearing and disappearing like a scent.

Installation view: Gemma Smith's Threshold (walls)

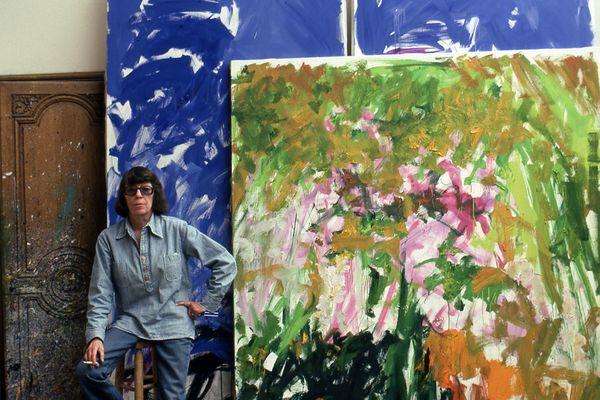

Gemma Smith in Part One of Know My Name: Australian Women Artists 1900 to Now. Smith’s 2019 painting Cusp is seen in the background.

Gemma Smith, Cusp, 2019, Courtesy of Gemma Smith and Sarah Cottier Gallery, Sydney.

Mary Webb, Joie de vivre, 1958, Collection: Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney. Purchased 2011.

Installation view: Gemma Smith's Threshold (walls)

Mikala Dwyer

Square cloud compound draws on the history of Cockatoo Island, a site which since colonisation has operated as a prison and an institutional home for young women. Dwyer grew up visiting the site and has had a ‘long engagement’ with its ‘ghosts’. The vibrant patchwork of materials in this work – including lamps, stockings, fabric and beer bottles – forms an oversized cubbyhouse that evokes a childlike sense of wonder and discovery and a means of escape.

Installation view: Mikala Dwyer

Mikala Dwyer, Square cloud compound, 2010, Collection: Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney. Purchased with funds provided by the MCA Foundation, 2015; Wall painting, 2020, Purchased 2020

Installation view: Mikala Dwyer

Kate Vassallo installing Mikala Dwyer, Wall painting, 2020, Purchased 2020

Installation view: Mikala Dwyer

Mikala Dwyer, Square cloud compound, 2010, Collection: Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney. Purchased with funds provided by the MCA Foundation, 2015

DI$COUNT UNIVER$E

In 2010 Australian designers Cami James and Nadia Napreychikov established DI$COUNT UNIVER$E and began creating fashion informed by social, political and feminist ideas. The group of works on display here comes from their Spring 2019 collection WOMEN and offers an unapologetic account of the experience of womanhood.

Debuting at New York Fashion Week in 2018, models marched down the runway in designs proudly emblazoned with the phrases ‘not for sale’, ‘bimbo’ and ‘hysterical’, a reclamation of terms traditionally used as insults and to objectify women’s bodies. Through text, colour and embellishment, other designs referenced biological processes associated with womanhood (reproduction and menstruation) that are rarely discussed publicly but often the basis of discrimination within professional and cultural contexts.

The development of this collection coincided with the escalation of the Me Too movement, a global response to the harassment of women. Although this movement exposed widespread gender discrimination, it was also criticised for primarily advancing the voices of white, cisgender women (who are assigned female at birth and identify as women). Those also experiencing oppression as women of colour and/or trans women were often left behind.

In contrast, James and Napreychikov have championed inclusivity since the label’s inception. For the WOMEN runway presentation they cast cis- and transgender models from a range of cultural backgrounds to represent the ways in which womanhood exists in contemporary society.

Installation view of Di$count Univer$e in Know My Name: Australian Women Artists 1900 to Now – Part One.

Installation view of Di$count Univer$e in Know My Name: Australian Women Artists 1900 to Now – Part One.

Installation view: DI$COUNT UNIVER$E

DI$COUNT UNIVER$E (fashion house): Cami James (designer), Nadia Napreychikov (designer), 'Not for reproduction' gown, Gift of the artists 2020

Installation view of Di$count Univer$e in Know My Name: Australian Women Artists 1900 to Now – Part One.

Jenny Kee and Linda Jackson

Since meeting and forming a creative partnership in the early 1970s, Jenny Kee and Linda Jackson have become pioneering figures in fashion design. Working collaboratively under their fashion label Flamingo Park, they drew upon a mutual love for the Australian environment, developing a distinct voice in fashion through bold garments and prints. They have also carved out significant design careers individually, with Kee well-known for her vibrant knits, and Jackson for her collaborative work with artists such as the women producing batiks at Utopia Station.

Installation view: Jenny Kee and Linda Jackson

Flamingo Park (fashion house), Linda Jackson (designer), Jenny Kee (designer), Opal Oz outfit, 1981, Gift of Jane de Teliga 1987.

Flamingo Park (fashion house), Linda Jackson (designer), Jenny Kee (designer), Universal Opal Oz outfit, 1984, Purchased 1985.

Bush Couture (fashion house), Linda Jackson (designer), Black rainbow opal outfit, 1985, Purchased from Gallery admission charges 1985.

Linda Jackson, Olga – Ayers Rock coat, circle top and dirndl skirt, 1980-81, Purchased 1981.

Deborah Leser, Opal Rainbowscape, 1983, Purchased 1984.

Installation view: Jenny Kee and Linda Jackson

Tania Ferrier, Shark bra and pants, 1988, Collection: Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth. Purchased 2019

Installation view: Jenny Kee and Linda Jackson

Flamingo Park (fashion house), Linda Jackson (designer), Jenny Kee (designer), Opal Oz outfit, 1981, Gift of Jane de Teliga 1987

Flamingo Park (fashion house), Linda Jackson (designer), Jenny Kee (designer), Universal Opal Oz outfit, 1984, Purchased 1985

Installation view: Jenny Kee and Linda Jackson

Bush Couture (fashion house), Linda Jackson (designer), Black rainbow opal outfit, 1985, Purchased from Gallery admission charges 1985

Linda Jackson, Olga – Ayers Rock coat, circle top and dirndl skirt, 1980-81, Purchased 1981

Installation view: Jenny Kee and Linda Jackson

Bush Couture (fashion house), Linda Jackson (designer), Black rainbow opal outfit, 1985, Purchased from Gallery admission charges 1985

Jo Lloyd and Phillipa Cullen

Archive the archive is inspired by the life and work of Philippa Cullen, a performance artist, dancer and choreographer who sought to generate sound through the movement of the body using theremin and early electronica. Despite the originality of her art, Cullen is now little known, having died prematurely at the age of 25 in the mid-1970s.

Despite never meeting Cullen, Lloyd conceived the performance as collaborative work in which she extends Cullen’s practice through her own. She wrote, ‘Here I am transmitting the actions of Philippa and what I know of her life, into a dance, 45 years after her death. I work with the thoughts that stimulate the dance; when we watch someone dance, we are watching the thinking. What was Philippa thinking? What dance did she not get to do?’

Jo Lloyd, Archive the archive, 2020, Photographer: Peter Rosetzky, Images courtesy of Jo Lloyd

Jo Lloyd, Archive the archive, 2020, Photographer: Peter Rosetzky, Images courtesy of Jo Lloyd

Jo Lloyd, Archive the archive, 2020, Photographer: Peter Rosetzky, Images courtesy of Jo Lloyd

Jo Lloyd, Archive the archive, 2020, Photographer: Peter Rosetzky, Images courtesy of Jo Lloyd

Jo Lloyd, Archive the archive, 2020, Photographer: Peter Rosetzky.

Barbara Campbell: Cries from the tower redux

Barbara Campbell’s Dubious letter (1992)—60 metres of hand-embroidered ribbon tacked together to form a skirt-shaped object—was suspended from the high ceilings in the Remembering gallery, centred to eye level, with generous space all around. This positioning allowed for a circular reading of the work’s embroidered text by any member of the public: Dubious letter created its own tacit participatory performance.

Cries from the tower redux premiered at the National Gallery of Australia in May 2021. Campbell took the inherent performative quality of Dubious letter and linked it back to the original context of the object within her solo performance Cries from the tower (1992), last performed in 1995 in the same gallery space.

For the Redux, Campbell invited three other performers, Hannah Bleby, Clare Grant and Agatha Gothe-Snape to build a multi-vocal, perambulatory reading-out-loud of Dubious letter’s embroidered text. The text is taken from ‘Letter III’ of the so-called ‘Casket letters’, dubiously attributed to Mary Queen of Scots and used to implicate her in the murder of her second husband, Lord Darnley. Campbell had embroidered ‘Letter III’ three times—in 16th century French, 16th century Scots and contemporary English—using historiographic documents.

The 2021 Redux began in similar fashion to the 1992 original: with the opening section of William Byrd’s Mass for four parts sung live by a solo soprano voice. On this occasion, Canberra-based soprano, Hannah Bleby sang the Kyrie eleison from a long vertical aperture high above the performers and audience.

As the high note fell away, Clare Grant began to walk carefully around the embroidered form, focusing her gaze on the lower section, reading the old French translation aloud, moving her eyes steadily upwards and pausing where the text joined with the 16th century Scots translation. At this point, Campbell took the lead in reading, with Grant following behind as an echo. When the text again changed to contemporary English in the top section, Agatha Gothe-Snape led the reading, the other two voices coming after, phasing in and out, overlapping, as all three wound around the work, increasing their walking pace in concert with the sharply narrowing conical form. As the readings concluded, Hannah Bleby sang the final section of Byrd’s Mass, the Agnus dei. Her voice remained suspended in air, like the embroidered object itself.

Barbara Campbell, 7 July 2021

Installation view: Barbara Campbell: Cries from the tower redux

Soprano singer Hannah Bleby performing Cries from the tower redux

Installation view: Barbara Campbell: Cries from the tower redux

Barbara Campbell and Clare Grant performing Cries from the tower redux

Barbara Campbell, Dubious letter from the performance Cries from the tower, 1992, Purchased 1995

Installation view: Barbara Campbell: Cries from the tower redux

Barbara Campbell, Clare Grant and Agatha Gothe-Snape performing Cries from the tower redux

Barbara Campbell, Dubious letter from the performance Cries from the tower, 1992, Purchased 1995

Del Kathryn Barton, the infinite adjustment of the throat…and then, a smile (detail), 2019, Courtesy of Del Kathryn Barton and Roslyn Oxley9, Sydney

Lindy Lee, The Unconditioned (detail), 2020, Courtesy of Lindy Lee and Sullivan+Strumpf, Sydney

Installation view: Barbara Campbell: Cries from the tower redux

Barbara Campbell performing Cries from the tower redux

Barbara Campbell, Dubious letter from the performance Cries from the tower, 1992, Purchased 1995

Del Kathryn Barton, the infinite adjustment of the throat…and then, a smile (detail), 2019, Courtesy of Del Kathryn Barton and Roslyn Oxley9, Sydney

Lindy Lee, The Unconditioned (detail), 2020, Courtesy of Lindy Lee and Sullivan+Strumpf, Sydney

Installation view: Barbara Campbell: Cries from the tower redux

View of the audience watching Cries from the tower redux

Kathy Temin, Pavilion garden (detail), 2012, Purchased 2017

Kathy Temin, Tombstone garden (detail), 2012, Purchased 2012

Lindy Lee, The Unconditioned (detail), 2020, Courtesy of Lindy Lee and Sullivan+Strumpf, Sydney

Installation view: Barbara Campbell: Cries from the tower redux

Barbara Campbell performing Cries from the tower redux

Barbara Campbell, Dubious letter from the performance Cries from the tower, 1992, Purchased 1995

Installation view: Barbara Campbell: Cries from the tower redux

Barbara Campbell, Clare Grant and Agatha Gothe-Snape following their performance of Cries from the tower redux

Kathy Temin, Pavilion garden (detail), 2012, Purchased 2017

Kathy Temin, Tombstone garden (detail), 2012, Purchased 2012

Part two: 12 Jun 2021 – 26 Jun 2022

Installation view of Know My Name Part 2: Heather B Swann, Herd 2001, Purchased 2017, Marion Borgelt, Lunar arc 2007, Purchased 2012 and Rosslynd Piggott, High bed 1998 (detail), Purchased 2000

Know My Name: Australian Women Artists 1900 to Now (Part two): opened 12 Jun 2021.

Know My Name is not a complete account; instead, the exhibition proposes alternative histories, challenging stereotypes and highlighting the stories and achievements of all women artists.

Told in two parts, works of art in part one made way for a new presentation that continues to propose alternative histories, challenge stereotypes and celebrate the achievements of over 250 artists.

Curators: Deborah Hart, Head Curator, Australian Art and Elspeth Pitt, Curator, Australian Art with Yvette Dal Pozzo, former Assistant Curator, Australian Art.

Yvonne Audette, The long walk, 1964, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1993 © Yvonne Audette.

Elisabeth Cummings, The Green Mango B and B, 2006, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2013 © Elisabeth Cummings/Copyright Agency.

Ewa Pachucka, Landscape and bodies, 1972, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1973.

Jean Baptiste Apuatimi, Tiwi people, Jikapayinga, 2007, purchased 2007.

Margaret Rarru Garrawurra, Liyagawumirr people, Pandanus mat, 2009, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2010.

Rosslynd Piggott, High bed, 1998, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2000.

Mazie Karen Turner, Everyday life in the modern world, falling into TV, c.1982, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2019

![Ethel Carrick, Esquisse en Australie [Sketch in Australia] 1908, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, Purchased 2023](https://media.nga.gov.au/BlytOZxc1wtzv22yIKT6vcZHJQA=/600x400///national-gallery-of-australia/media/dd/images/MicrosoftTeams-image_3_1KcJyco.png)