Max Dupain

Photographs

16 Nov 1991 – 27 Jan 1992

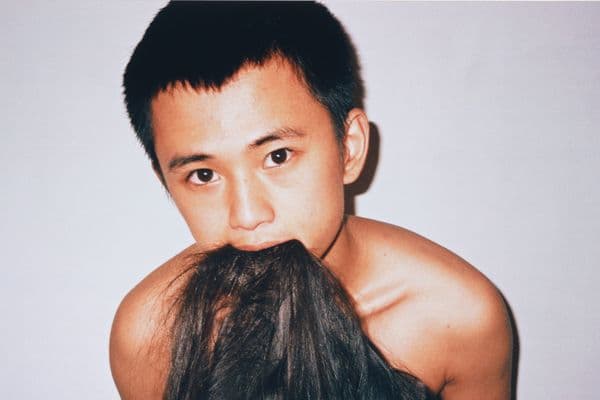

Jill White, Portrait of Max Dupain, 1989, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, Purchased 1991.

max dupain biography

'… there are photographers with a great sense of discipline, who work with unsophisticated equipment and who possess an acute sense of selection and spontaneous composition. They are able to extract every ounce of pictorial sensibility from their subject, and I support their doctrine to the last. Sensitivity, piercing awareness, emotional and intellectual involvement, self-discipline are some of the elements which create that rapport with the subject…

Max Dupain and his wife Diana live in Castlecrag in a house in the modern style which they had designed for them by Arthur Baldwinson in the late 1940s. It is flanked by magnificent gums — Angophora costata — that are native to the coastal areas of Sydney. The front garden facing the road is filled with flowering plants that have been tended carefully over the years. The back of the block slopes steeply down to the water and is intact with its native bush. Many of Dupain's recent still-life photographs have been made at home, often in the garden. However, Dupain continues to be actively involved in the business Max Dupain and Associates, which has recently relocated to Reserve Road, Artarmon, a relatively short drive from Castlecrag.

Maxwell Spencer Dupain was born in Ashfield, Sydney, on 4 April 1911 to George and Ena Dupain; he was their only child. George Dupain was a physical education teacher and a pioneer in the fields of physical education, biochemistry and nutrition, he virtually introduced the concept of physical education to Australia. Dupain grew up surrounded by books — his father had an extensive library of over 10,000 books, many of which are now in the photographer's own library. Music was another integral part of family life and Dupain continues to love classical music. Weekends were often spent at Newport Beach, where George Dupain built a weekend house which is still in the Dupain family.

In 1924 Dupain's uncle gave him his first camera, a Kodak Box Brownie. It was followed two years later by a vest pocket camera, a gift from his great-grandmother, 'during my struggle with the Intermediate Examination, thus ensuring complete failure in all following subjects! I salute her — It was a good thing!' (1947). Dupain became a serious amateur photographer while still at school and 'tried to reconcile mechanically reproduced image with the poetic sentimentality of youth' (1947), At the age of seventeen he joined the Photographic Society of New South Wales where the contact with photographer Harold Cazneaux was significant. Dupain later described Cazneaux as 'the father of modern Australian photography. He paved the way, struggling, in somewhat splendid isolation' (Harold Cazneaux, 1978). Dupain's first photographs were in the romantic Pictorialist style perfected by Cazneaux and other photographers from the older generation.

Dupain attended Sydney Grammar School from 1925 to 1930, 'five indistinguishable years (apart from the rowing!)' (1986). After completing school he began an apprenticeship in Cecil Bostock's photographic studio in Sydney: 'l spent three years with this very thorough craftsman and the study of his exacting and original methods formed a solid background for my future work and development… I owe a great debt to him' (1948). In the evenings Dupain studied painting and drawing, initially at the Julian Ashton Art School under Henry Gibbons, a painter in the modern style, and later at East Sydney Technical College. Particularly important to Dupain were the passionate discussions that followed the classes when he and a few other students met over coffee.

In 1934 Dupain opened his own photographic studio at 24 Bond Street, Sydney, and quickly established a reputation as Australia's leading modern photographer. Informed about developments that had occurred in photography, especially in Europe, Dupain dispensed with the softness and gentleness of the Pictorialist style that had enjoyed an untroubled reign since the turn of the century and began to work in the modern style. His bold, innovative photographs quickly made an impact on the Sydney scene at a time when the demand for photographic illustrations was beginning to recover after the Depression. Dupain's talents were recognized by the publisher Sydney Ure Smith who presented a portfolio of the young photographer's work in Art in Australia in 1935. Many of Dupain's fashion photographs and advertising images produced for the David Jones department store appeared in Ure Smith's prestigious magazine The Home. Dupain later paid tribute to Ure Smith: 'No tribute can be too high or too glowing for this great lover and promoter of art and photography in Australia. Without being authoritarian in any way whatsoever, he influenced our art world as much as Julian Ashton' (Harold Cazneaux, 1978).

During the thirties and forties Dupain's photographs appeared in a variety of publications, including Oswald Ziegler's book Soul of a City, 1937, which was designed by Douglas Annand; and Helen Blaxland's Flowerpieces, 1946. In 1948 Ure Smith published a monograph on Dupain's work from 1935 to 1947.

Dupain actively championed the modern style in his own photographic work and in other activities: in 1935 in Art in Australia he favourably reviewed the experimental photography of Man Ray, the avant-garde American-born artist who worked in France; and in 1938 he was one of the founding members of the short-lived Contemporary Camera Groupe, Sydney.

Dupain's career in the 1940s was dominated by his war service, from 1941 to 1946. In 1941 Dupain entered into a partnership with the photoengraving firm Hartland & Hyde that was to last for fifty years, and relocated to 49 Castlereagh Street, Sydney. Olive Cotton, Dupain's first wife, ran the studio during Dupain's extended absence. In the early years of the war Dupain was a camouflage officer in the Royal Australian Air Force; he was involved in designing and building camouflage screens to cover new oil tank installations in Darwin, and in the research and reporting on the camouflage work being done in the New Guinea area by the Americans and Australians. In 1945 Dupain resigned from the Department of Home Security and joined the Department of Information as a photographer 'covering as much of Australia's way of life as possible for overseas publicity. My work was to be directed at potential migrants' (1986). He travelled extensively and visited all the capital cities except Darwin.

At the conclusion of the war Dupain returned to the studio and dramatically changed his direction: 'the unstable war-time years, the grudging adaptation to ever-changing surroundings, the thousands of impressions … of varying environments, all added up to long-term shock. I did not want to go back to the "cosmetic lie" of fashion photography or advertising illustration' (1986).

As a result of his war-time experiences and contact with documentary photographers and filmmakers (especially his friend Damien Parer), Dupain became committed to documentary photography. He adopted the credo put forward by British documentary film-maker John Grierson and gave Grierson's now famous statement — ‘the creative treatment of actuality' — a particular Australian inflexion. In 1947 Dupain wrote: 'l want to use more sunlight in my work. The studio has an odd flavour about it now and the artificial quality of half-watt lighting does not ring true alongside sunlight. We have it here all the year round — so why not make use of it! . . . The point is that photography is at its best when it shows a thing clearly and simply. To fake is in bad taste. The studio is synonymous with fake'. It was from this point onwards that Dupain became committed to developing and championing a national photography that 'will contribute greatly to Australian culture. Let one see and photograph Australia's way of life as it is, not as one would wish it to be'. The crux was light, the bright sunlight and blistering detail that he took to be essentially Australian. Working outdoors was also crucial.

In the late 1940s Dupain began to specialize in architectural photography: 'l always had a hankering for architecture. In my youth I made drawings from reproductions of Greek temples and capitals' (1986). Although he seriously considered becoming an architect, 'mathematics and physics were my undoing. I was thrown at any attempt to understand either. But eventually there developed another way of getting involved — through photography' (1986). It proved to be a fruitful decision as Dupain considers some of his best work to have been in the field of architecture. Dupain's specialization in architectural photography has resulted in fine photographs of both modern and historic Australian buildings that have been extensively published, for example, in the books Francis Greenway — A Celebration, 1980, Old Colonial Buildings of Australia, 1980, and Fine Houses of Sydney, 1982. They have also been included in various exhibitions, notably Australian Built: Responding to the Place, a photographic exhibition of recent Australian architecture that toured Australia. One of Dupain's first architectural jobs was with Harry Seidler, with whom he has continued to work.

As a result of the collaboration with Seidler, Dupain made his first, and only, trip to Europe in 1978 to photograph the Australian Embassy in Paris. He has also worked in Bangkok, where he photographed Ken Woolley's Australian Embassy. Dupain has chosen not to be a traveller: 'Working as a professional photographer in insular Australia has been my self-chosen lot' (Light Vision, 1978). However, he believes that this has had a positive outcome and has resulted in the distinctive quality of his work and its Australian character: 'So one is thrown up against one's inner resources … Direct influential impact is at half-strength capacity. I think this is a good thing if you have the courage and endurance to sustain and promote your individuality by sheer brute assertion of belief in yourself. God help those who can't muster this will unless they migrate, absorb and return to us, temporarily stimulated and refreshed, but possibly as other human beings lost to their real selves in the wilderness of the world's pictorial paradise' (Light Vision, 1978).

Since the 1930s Dupain has held numerous exhibitions in Australia and overseas, only a selection of which are mentioned here. In the early 1930s he contributed photographs to the Paris Salon, the London Salon, and the Victorian Salon of Photography. His photographs were included in Australia's 150th Anniversary Celebrations in 1938; in Six Photographers, Sydney, 1955, Photovision, 1964, and other exhibitions. He has held many one-person exhibitions since the 1970s, for example at the Australian Centre for Photography, Sydney, Powell Street Gallery, Melbourne, Church Street Photographic Centre and Christine Abrahams Gallery, Melbourne. In 1980 a retrospective exhibition curated by Gael Newton was held at the Art Gallery of New South Wales and accompanied by her catalogue Max Dupain. In 1988 he was included in The Great Australian Art Exhibition and produced the portraits for the Cancer Council portfolio The Bicentennial Collection: A Portfolio of Australian Artists. Also in 1988 he was commissioned by the Orange Regional Gallery to photograph the area and its people; the resultant photographic essay was presented in an exhibition accompanied by the catalogue To Orange With Love. A touring exhibition of Dupain's dance photography of the 1930s was held in 1990.

Recent publications of Dupain's photographs include Max Dupain's Australia, 1986, and Max Dupain Australian Landscapes, 1988. In 1991 , to celebrate Dupain's eightieth birthday, a limited edition book of his photographs was published by Richard King, Sydney, who also promoted five portfolios of Dupain's photographs (Sydney Nostalgia), Also in 1991 exhibitions of his photographs have been held at the Mitchell Library, Sydney, and at the Blaxland Gallery, Sydney. A biography of Max Dupain is currently being written by Clare Brown.

Dupain's photographs have been exhibited overseas — for instance at the Photographers' Gallery, London, in 1981 and 1991, and at the Staley-Wise Gallery, New York City, in 1987.

Dupain has been the recipient of many honours and awards, including an OBE which was awarded in 1982. Also in 1982 he received the Commonwealth Medal 'Photographer of the Year' from the Federation of Australian Photographers. The following year he was made an honorary fellow of the Royal Australian Institute of Architects. In 1991 Dupain's image Bondi was published on a stamp issued by Australia Post to commemorate the 150th anniversary of photography in Australia. Through his long career as a photographer and as a commentator on photography — for example, as photography critic for the Sydney Morning Herald — Max Dupain has passionately championed the dual causes of straight photography and a national photographic style. He continues to devote himself to his work, especially his current series of still-life photographs.

Helen Ennis

Suggested Further Reading

The quotations from Max Dupain in this essay have been taken from the book Max Dupain's Australia (Viking, 1986); the essays ‘Australian Camera Personalities: Max Dupain' published in Contemporary Photography (volume 1, number 2, January-February 1947), 'Max Dupain', Light Vision (number 5, May-June 1978) and 'Caz — An Appreciation', in Harold Cazneaux (National Library of Australia, Canberra, 1978); and the foreword to the catalogue Max Dupain: New Work, Old Work and Very Old Work (Australian Centre for Photography, Sydney, 1983).

Gael Newton's catalogue Max Dupain (Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 1980) continues to be one of the major starting points for research on Dupain's life and work. In addition to the books mentioned in the essay, Dupain's photographs have been published in Max Dupain (Ure Smith, Sydney, 1948), Max Dupain's Australia (Viking, 1986) and Max Dupain's Australian Landscapes (Viking, 1988).

Dupain's own writings on photography have been published in professional photography magazines and as criticism for the Sydney Morning Herald. For an interesting analysis of Dupain's newspaper criticism see Helen Grace, 'Reviewing Max Dupain', Art Network (number 9, Autumn 1983).

Max Dupain's photograph The sunbaker has been discussed in depth by Gael Newton in Creating Australia: 200 Years of Art 1788-1988 (ICCA and the Australian Bicentennial Authority, 1988) and Geoff Batchen's article 'Creative Actuality: The Photography of Max Dupain' in Australian Art Monthly (November 1991).

Interview with Max Dupain

Max Dupain spoke with Helen Ennis at his home in Castlecrag, Sydney, on 1 August 1991. Helen's questions (in italics) and Max Dupain's answers follow.

How did you come to photography with such assurance?

The answer was and probably still is that I couldn't do anything else — as simple as that. I had no scholastic background at all but I latched onto photography immediately. The intrigue of producing a light picture the way we had to in the 1920s and earlier was so fascinating that it has stayed with me all my life.

You have mentioned that you loved rowing and that athletics were important to you when you were at school. Could you have pursued those interests?

I don't think so, I think that might have been a follow-on from my father's physical education situation. He was the doyen of physical education in Australia, had a marvellous gymnasium which I used to attend, and physical health and all that applied to it was his paramount interest in those days. I followed through with school sport, I rowed a lot and later when we came to live at Castlecrag on the water I had a scull, which I paddled for fifteen to twenty years.

Did this awareness of physical health mean that you were really conscious of nutrition?

Oh yes, for sure. I'm just trying to think of the phraseology. At that time we didn't have a science of dietetics but it was a case of eating what we knew was best for us — carbohydrates, mineral salts, fats, vitamins and so on — and it still is. That's the physical bit and all we can do is hope for the best, It may work out or it may not. So far it's been pretty good — there's not much longer to go.

Was your mother interested in that kind of lifestyle too?

She was very devoted to my father and gave him all the support that a wife would be expected to give; she naturally followed his dietetic procedure. They lived a very simple life. I was the only child. My father had an enormous library, probably 10,000 books, of which I have many in my own library. He had a laboratory where he used to make chemical experiments and he became a Fellow Storm at Toowoon Bay. 1950s, printed 1990 of the Chemical Society in London when I was a small boy, much to the ecstasy of the family generally. This was due to his analysis of various aspects of the human body in chemical terms — and it was great to have, especially in those days.

As a family, what did you do in your free time?

We were a very simple family, we didn't have all the sophistications of life that we have today. Occasionally we'd indulge in extraneous entertainment like a picture show, visits to the art gallery and not much else. Comparatively speaking, a simple life which is something I hanker after today.

What about music, were your parents interested in music?

Yes they were. We had a marvellous Edison gramophone and my father was interested, primarily because his father played the piano. We had all the classics, Beethoven, Tchaikovsky, Schubert, and the rest of them. I'd say every day we had music of some sort at some time.

Is there anything else you want to say about your family or your childhood?

No, but I can't overstress the simplicity of it. No complications as far as society was concerned and life was lived as it more or less happened to be.

Did you go to the beach house at Newport very often?

Yes, we did. The house at Newport was built when I was about ten. A timber house, very elemental. It's still there, it's had additions to it and some renovations. I can remember the weekends were sacrosanct and more often than not they were spent at the Newport cottage. We lived at Ashfield and we used to take a bus, tram, the boat, the tram and the bus to Newport. It took three hours and we considered this a long time but well worth it. I can remember when I was a small boy arriving there just before lunch, slipping into a costume and diving down the cliff into the surf on a beautiful sunny day. I wish to hell I could do that now.

During your apprenticeship with Cecil Bostock you studied drawing and painting at night classes at Julian Ashton Art School and then at East Sydney Technical College. You have said that you gained your 'basic art wisdom' from Henry Gibbons. What did that mean?

The basic bit is that the foreground is the most important part of the picture. I was interested in landscape painting at the time and one of the reasons I went there was to learn to more or less draw and claim what wisdom I could from the atmosphere, the teaching, the talking and so on. There was a group of us there, about four or five of us, old friends, one architect, one builder, a secretary and maybe a couple of others. We used to go to coffee after art classes two or three times a week and argue, and this was marvellous. My greatest friend at the time was Chris van Dyke who was a builder, terribly interested in architecture, and his favourite exclamation was ‘you're only young once, make the most of it!' Well, you know that was just part and parcel of the development cycle. I was into photography and I never let up on that and I'm still that way.

How did you keep yourself so well informed about photography?

Books like Das Deutsche Lichtbild were available in Sydney and we used to subscribe to them. I think we got them through Swains bookshop primarily. We just used to dwell on them; when Das Deutsche Lichtbild arrived on the scene we'd just hoe into it to see what they were thinking on the other side of the world. This was great, you know Ultimately it wore out and you developed your own scene, your own philosophy, your own thinking. Now you don't give a stuff what happens overseas because you've got your own thing to do, naturally enough.

You have been described as 'the quintessential Australian photographer'. What do you think people mean by that?

I don't know and I'm not quite sure that they know what they mean either. It could mean that I have a very specific devotion to my country, which is Australia. I find that my whole life, if it's going to be of any consequence in photography, has to be devoted to that place where I have been born and reared, and worked, thought, philosophized and made pictures to the best of my ability. And that's all I need.

When people talk about your work being really Australian', I guess they might mean its subject matter, but do you think of it more as your approach?

I do. It's my philosophy primarily which is directed in no uncertain terms towards my own country.

Would that be one of the reasons why you have made only one trip to Europe [in 1978]?

Yes, could be.

Did you have the desire to go earlier?

No, I had no desire to go at all. When one is in business and there is no alternative, you just have to abide by the situation and do it.

So your trip to Europe and Bangkok [c. 1980] obviously didn't fill you with the desire to pack your bags and travel regularly?

No, no. The skittering around the periphery doesn't interest me one little bit. I like to involve myself in, maybe, a small area geographically and work it out, as simple as that.

Have you felt restricted in getting a lot of art education and art appreciation from reproductions in books?

No, no. I think you take them for what they're worth. They are stimulants up to a point and you just accept them as that. But the real thing has got to be the thought they promote within. Without that you might as well just take up photography as most people do, as a technical procedure. That's nowhere near enough, for me anyhow.

Over the years do you think your inspiration for photography has come from photography or from the other arts?

No, not from the other arts. You may find a basic ingredient there, but it's not a conscious one for sure. I think my development would be totally due to my own indulgence in photography, my experimentation, and learning by default and the agony of failure. But in the long run, it's all added up.

You told me earlier that poetry particularly has been a lifelong passion. Do you think your interest in literature and music too have a bearing on the way you work as a photographer?

For sure. I think the subjective comes into it very, very strongly in that respect, especially with music, which is a nebulous stimulant and inspiration. Poetry is the same thing… Going to work sometimes I find myself mouthing Shakespeare or T.S. Eliot or whatever. I don't know whether the drivers of the adjacent cars think I'm swearing at them or what! But it just happens that way.

What about music, what are your tastes now in music?

I'm still addicted to the classics. I nominate Beethoven as number one. See, life's too short, I haven't got time, time to listen to Tchaikovsky and Beethoven and some of the others and at the same time try to assimilate what's going on at the present moment.

Are you interested in current affairs?

Oh yes, politics and whatever goes with it. We watch the news every night. As far as I'm concerned that's the bright spot of the night. There's great peace in getting home from work — a hard day achieving what I have to achieve in the studio — and sitting by a fire with a meal watching somebody else do a bit of work.

What about bed-time reading, what are the kinds of books that you'd pick up to read if you had the time?

I used to read in bed regularly but if I start doing it now I drop off not long after I get started! I don't have much time for reading, which is a pity. I intend to try and rectify that. I just got T.S. Eliot out the other day to give him a go again.

I grow old… I grow old

I shall wear the bottoms of my trousers rolled.

… Do I dare to eat a peach?

I have heard the mermaids singing each to each.

I do not think that they will sing to me.

(The Love Song of J Alfred Prufrock)

Does he seem to be the poet of despair when you read those things?

I hadn't thought of that. There's a cynical quality about T.S. Eliot that's very penetrating. I think he's tremendously observant of life and he's able to put it down in such brief, succinct terms. I think it's marvellous. I love Shakespeare, especially when a situation requires me to sound forth with great opposition.

Do you know Shakespeare's work by heart?

Yes, that which I learnt at school. We had marvellous teachers of Shakespeare. I think if you knew Shakespeare back to front that's all you need, that's all you'd want, that's got everything philosophically.

What is your favourite picture?

Maybe it's one I haven't done yet. The meat queue is probably one that I revere more than most. There's the recent ones [still lifes] like the pumpkin and the butterfly, and the dead bird on the newspaper with a candle. I feel the still lifes I'm doing now will possibly overshadow a lot that's been done before. There are many reasons for this, maybe because I'm 'cabin'd, cribb'd confined, pent up to forty thousand doubts and fears' insofar as the studio operations are concerned. We'll have to see about that but I dearly recall landscape and I think, before long, I will be back into the landscape field of photography. I'm looking forward to that.

What is it about doing a still life that gives you so much pleasure?

You have the opportunity to relate to so many things that are at odds with each other, like the bird and the candle. I have something else in mind which I haven't done yet — this marvellous wisteria vine, the roots of which climb up in an integrated system of lines and curves; I'm looking for a beautiful butterfly to put on the vine and then I'll photograph it — maybe by night with artificial light. Still life has a wonderful range of possibilities as far as form and content are concerned. With a still life you can arrange or rearrange or do what you like. It becomes a very, very personal exercise that you have total control over.

What makes you want to place a butterfly on the vine?

It's an outdoor thing and I've seen them flying around the wisteria. It has an unusual cognizance with those marvellous curling branches — in contrast, and also in sympathy, depending on how you approach it. It would have a dramatic quality too, especially if it were done at night with artificial light. Drama is something that I’ve always been rather akin to — only insofar as lighting is concerned, not necessarily subject matter.

What is it about The meat queue that pleases you?

I was doing a series of pictures for the Department of Information at the time. We were doing a story on queues after the war. They were all over the place — queues for buses, vegetables, fruit. I just happened to come across this butcher shop in Pitt Street, I think it was. Here they were all lined up, and I went around it, took a number of pictures, ultimately ending up with this sort of architectural approach with four or five females all dressed in black with black hats, not looking too happy about the world. Suddenly one of them breaks the queue when I'm focused up all ready to go, pure luck. She breaks the queue and the dame next to her gives her a pretty demoniac look wondering why, and we took a picture. That was it, it broke up. There's an awful lot of luck in photography. Sheer luck! It sort of makes the situation. That's photography, you couldn't do it any other way.

Do you like photographing people?

With reserve. I suppose I'm a still-life man basically, into architecture and other things. Strangely enough, though, most of my best pictures are involved with people.

Are there boundaries between your commercial work and your personal work or do you feel that you can move quite freely between them?

I'm an addict for versatility. I got this from my old boss Cecil Bostock. Well, you know, in those days you couldn't just specialize in architecture or portraiture, you had to be able to do everything. It was marvellous training as far as I was concerned. Whatever subject matter you come up against you make the most of it, without any reserves.

I did want to touch on The sunbaker, one of the most famous Australian pictures. Do you have any explanations for its fame?

No, but I'm a bit worried about it. I think it's taken on too much — so much so that you feel that one of these days they'll say 'that bloody Sunbaker, there it is again!'. It was a simple affair. We were camping down the south coast and one of my friends leapt out of the surf and slammed down onto the beach to have a sunbake — marvellous. We made the image and it's been around, I suppose as a sort of an icon of the Australian way of life.

Actually I recently heard it said that you couldn't take that photograph in good conscience now because of all the fear about the sun.

I thought of that. It might come up as a new image altogether, sooner or later.

You have photographed Sydney a lot over fifty years. How do you feel about the way Sydney is going?

I think it's a pretty poor show — overdevelopment in many respects. This is all conducive to pollution and all the by-products that civilization creates which in turn destroy civilization. I dread to think what the place is going to be like in another twenty or thirty years.

If you were set a project to photograph Sydney would you look for the old parts of Sydney or do you still have a love affair with the modern?

There are some marvellous buildings in Sydney, for sure, some wonderful concepts. But it's the people that are the worry. There are just too many of them, and too much space is devoted to bricks and mortar and not enough space to natural organic situations. Le Corbusier had a marvellous scheme many years ago in Paris, where he designed — they never got off the ground — high-rise buildings with marvellous separations and parks and trees throughout. The capitalist system won't permit that, every square inch is valuable in the money sense. Corb's idea was purely idealistic, which would never, never come to pass now.

Have you ever estimated how many photographs you have taken?

No. We’ve just moved, as you know, and the filing cabinets full of negatives are so daunting.

With regard to the photographic process, do you like printing?

I'm addicted to printing. I think it's the final stage of the sequence of making a picture. I always think that there's a series of stages in making a picture: the exposing of the sensitive film, producing the negative, printing and finishing it off. These processes have chemical solutions that are enormously important in the control of the print quality. Once you get that lined up your photography becomes a sequence of events with a certain amount of control of those events. You can forget everything else except for the concentration that you must have on the subject matter itself and the analysis of that subject matter in pictorial terms. That's the new thing: every time you take a picture, you have to assimilate what's there and turn it into photographic terms through the process that I've just mentioned. Okay, well, it takes time. I hate to say it but I always tell young photographers who come to me and ask advice in this respect that the first million are the worst.

Have you always printed your own images?

Well, I suppose for the last sixty-five to seventy years I have, that's good enough! There was a time when I remember tripping down to the chemist with a roll of film and asking for it to be processed and printed. That's a long, long time ago.

How many prints might you make to get something that you're happy with?

Three to six. It's generally three, three prints to get one and maybe more. But you're lucky if you get away with less than three. And it's expensive, though necessary.

There have been obvious changes in your printing style over the years as one would expect. Why are the photographs from the last ten years darker?

I’ve always been interested in the dramatic and I discovered that black is a very important ingredient of dramatic quality. You'll find that many of my negatives of serious photography involve a lot of clear space which is the reverse on the print — in other words, black or thereabouts. It's a situation of simplification to a large extent, insofar as photography has a marvellous tonal range. But you can interpret this and simplify it considerably by reducing that tonal range while retaining the photographic quality which infers that black is the basic ingredient. On top of that you can have some beautiful subtleties of halftones and highlights which are emphasized by the black. You'll find a lot of my work is like that.

In your recent still lifes you have used artificial lighting at night. Is that also for a sense of drama?

Soft reflected light is rather marvellous. It might be artificial but I found that the flowers, for instance, are wonderful at night. When you do them at night, even with added artificial light, you can bring them to life in their own sense rather than rely on context, which is inclined to distract and destroy the vital bit. You'll see that with most of the flowers — the magnolia, the rock lily and many others — and with the shells; different but marvellous forms. I've just gone out of my way in a photographic sense to bring them to life and emphasize their particular forms.

You've travelled widely in Australia. Where are the places that you'd like to photograph most?

Well, there's the wonderful luscious landscape of the Cairns area with undulating hills and God knows what not. The Kangaloon situation in the Southern Highlands; Western Australia has got some wonderful stuff in the coastal regions; up through the Simpson Desert and the Gibber Desert to Darwin. It's a big place, Australia, and looking back on it now I can only recall a few things. It gave me a perspective on life in the city, where I'd been born and bred, and made me aware of one of the wonderful qualities about Australia that I admire so much — a wealth of desert and no people!

How did you come to work for the Department of Information during the war?

The Information set-up was run by Ron Maslyn Williams at the time and he offered me this job. I was in the air force taking pictures for quite a long time and I thought, oh bugger this, this place is just disintegrating (the war was nearly finished). I was going to apply for a job as a war photographer and see if I could get out in amongst it again. Ronnie heard this and he said, 'we'll keep you in Australia I think and do what we can with you here', and I was sent by the Department of Information all round Australia to make pictures for publicity in respect of migration. This was the big thing in those days, to get people into Australia, so we did that. It was quite an experience.

If commercial work hadn't kept you so busy, what would you have done?

Oh, I would have been into my own thing as I am now. This ideal situation is what used to occupy my thoughts, my secret thoughts. Advertising, illustration and fashion photography, and all that goes with it, was a means of staying alive. It's rather a strange thing that my early boss Cecil Bostock used to say, 'I’ve made my reputation out of pictorial photography, and look what I have to do' — which would be trite advertising illustration and all that goes with it. In a sense it did its job as it made us versatile and able to handle anything that came to pass. Ile still got that. You'll see a certain amount of versatility, portrait work, for instance, which I find the most difficult of all, landscape, illustration, architecture, still life. That's where it originated — in the times when we just had to do it and nothing else.

What were your most difficult photographic assignments?

They're all a struggle. When I get an assignment to do, it might be a building or whatever, I'll go and look at it. I might think about it for days before I attempt to throw a camera at it.

When I look at your work from the early thirties it still looks incredibly dramatic in comparison to other work at the time. It's so different and so bold and yet it did get taken up very quickly Sydney Ure Smith seemed to have the confidence to say 'okay this is where the energy is, let's publish it and make it work'.

He was a great standby for me.

Although at that time you were in your early or mid-twenties, he obviously didn't hold your youth against you.

No, no, he didn't do that, he was interested in results. Forever and ever amen I'll be grateful to him for that, as I've said so many times. He and Julian Ashton were the two people in Sydney that just about controlled Australian art. Ure Smith with his publications Art in Australia, The Home magazine and others, and Julian Ashton with this marvellous school of art which I went to for a while. Not to much effect, but it was all good experience.

Is there anything you would like to add for posterity?

[Harold] Cazneaux is the bloke who hasn't had enough emphasis in this country. He was a great individual, in spite of the fact that he was a Pictorialist and his inspiration and tutoring came from England, where the Pictorialist movement originated. There was the Sydney Camera Circle: he was one of the founders, with Cecil Bostock, [James] Stening and about half a dozen people. You don't hear about it much now. They produced probably some of the best work in Australia at the time. Well, that's all part of the sequence of events in Australian photography and no doubt it will be recorded as such, I have a lot of respect for Cazneaux and, in spite of the overriding pictorial influence, he had individual qualities which he expressed in his work. Like the photograph on the stamps, The wheel of youth. But he was into Australian light and Australian activity in an almost documentary manner, but not quite, and a lot of his work was extremely individual for those days.

In art between the wars do you think that light was important?

Photographically, certainly.

What kind of light is it? How would you describe it?

In contrast to European light it's brilliant, it casts a great shadow, but it's wonderful to see it and use it the way you want it. You don't just accept it as light, it's got to be something else. It's got to be coming from a direction in relation to the subject matter that you're operating with. That's why we often go and look at a building before we have to photograph it, just to see what its orientation is and make a decision: 'right, we'll do this western side at such and such a time, northern side at such and such a time'. This is terribly important. But the quality of light here is marvellous, it's clear without any inhibitions, and you know, we just accept it.

Anything else you'd like to mention?

What was I going to wind up with? Llewellyn Powys's philosophy, 'l am nothing, I was nothing. Eat bread, drink wine, make love, come'. This is on an old Roman gravestone that he found somewhere and he quoted it at the end of his philosophical treatise called Impassioned Clay. It sort of negates the other things that I’ve just said.