Robert Rauschenberg

1967–1978

1 Sep 2007 – 27 Jan 2008

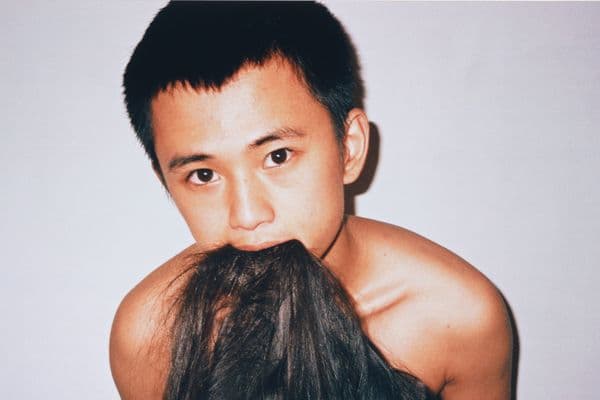

Robert Rauschenberg, Horsefeathers thirteen – XV 1972 from the Horsefeathers thirteen series, 1972–76 purchased 1973, © Robert Rauschenberg. Licensed by VISCOPY, Australia, 2007

About

Robert Rauschenberg moved to New York in 1949, at a time when the avant-garde art scene was dominated by Abstract Expressionism. Right from the beginning, Rauschenberg worked beyond the restrictions imposed by media, style and convention, and adopted a unique experimental methodology that combined gestural mark-making with its antithesis – mechanically reproduced imagery.

His work has been of central influence in many of the significant developments of post-war American art and has provided countless blueprints for artistic innovation by younger generations.

Exhibition Pamphlet Essay

'Beauty is now underfoot wherever we take the trouble to look.' [1]

Robert Rauschenberg has had an extensive impact on late twentieth-century visual culture. His work has been of central influence in many of the significant developments of postwar American art and has provided countless blueprints for artistic innovation by younger generations. Rauschenberg’s radical approach to his artistic practice was always sensational, with the artist producing works so experimental that they eluded definition and categorisation. The National Gallery of Australia holds an important collection of Rauschenberg’s works. These works exemplify the artist’s striking transition in subject matter and material during the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s – a shift from the imagery of American popular culture to a focus on the handmade and unique combinations of natural and found materials. Many of the works exhibited in Robert Rauschenberg: 1967–1978 reveal the artist’s overarching aim to ‘drag ordinary materials into the art world for a direct confrontation’. [2] It has been Rauschenberg’s perpetual mix of art with life that has ensured that his work appears as innovative today as it was 40 years ago.

The legendary Bauhaus figure, Josef Albers, was the head of fine art at Black Mountain College, North Carolina, when Rauschenberg enrolled in 1948. Under the supervision of the strict disciplinarian, Rauschenberg learnt about the essential qualities, or unique spirit, within all kinds of materials. Rauschenberg said of their student-teacher relationship that Albers was ‘a beautiful teacher and an impossible person. He didn’t teach you how to “do art”. The focus was on the development of your own personal sense of looking. Years later … I’m still learning from what he taught me. What he taught me had to do with the whole visual world’. [3]

It was also at Black Mountain College that Rauschenberg came into contact with several other key art world figures who had a vital and long-lasting impact upon his thinking and artistic pursuits. The artists Ben Shahn, Robert Motherwell, Willem de Kooning, Jack Tworkov, Franz Kline and Aaron Sisskind were all teaching at Black Mountain. However, the most significant influence on the young artist was the celebrated avant-garde composer John Cage. Rauschenberg and Cage developed a relationship of reciprocal inspiration – a connection that provided both the artist and the composer with the daring that was required in the creation of their most innovative works.

In contrast to the environment of Black Mountain College, the New York avant-garde art scene in 1949 was dominated by Abstract Expressionism. The artistic giants Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock had established themselves as the most innovative of the Abstract Expressionists. Discussions focused on the inner emotional state of the individual artist as expressed in highly charged painted gestures. The more free-thinking Rauschenberg, however, worked outside these confines, adopting a methodology that sought to reunite art with everyday life, an ideology that was in complete opposition to the central tenets of Abstract Expressionism. Early in his career, Rauschenberg created controversy within the New York art scene with a series of ‘artistic pranks’, including his infamous erasure of a Willem de Kooning drawing. This rebellious act of destroying an established artists’ work gained him instant notoriety and secured Rauschenberg the position of New York’s enfant terrible.

Despite his ‘prankster’ reputation, Rauschenberg was highly self-disciplined and determined to challenge himself. In 1951, he completed a series of white paintings, which were in contrast, followed by a series of black paintings. By limiting himself to a monochromatic palette, Rauschenberg performed an artistic exorcism, rendering the restrictions imposed by media, style and convention obsolete so that there were no psychological boundaries to what he could do from that point onwards. Only after such self-imposed regulation was Rauschenberg prepared for what he was to attempt next. In a radical transgression of artistic conventions, Rauschenberg began to fuse vertical, wall-mounted painterly works with horizontal, floor-based sculptural elements, usually in the form of found objects. His fusion of the two-dimensional picture plane and the three-dimensional object is now of legendary status. It was the invention of a new ‘species’ of art, which Rauschenberg termed ‘Combines’.

Rauschenberg developed his own unique style by combining gestural mark-making with its antithesis – mechanically reproduced imagery. It was this remarkable clash of visual elements in Rauschenberg’s art that provided a major aesthetic fracture – a departure from the heroic painterly gestures of Abstract Expressionism and a move towards the adoption of popular culture as subject matter. This radical schism, however, would not have occurred had it not been for Jasper Johns, with whom Rauschenberg had a long and intense partnership, beginning in 1954. Rauschenberg and Johns lived above one another in the same building, visiting each other every day and setting artistic challenges for each other. Rauschenberg has said of his partnership with Johns that, ‘He and I were each other’s first critics … Jasper and I literally traded ideas. He would say, “I’ve got a terrific idea for you” and then I would have to find one for him’.[4] The Rauschenberg–Johns relationship was one of the great creative relationships of the twentieth century. It not only propelled them both in radically new directions, but was also a meeting of two minds that contributed to the development of the Pop Art movement.

If there is an overarching methodology that provides a foundation to Rauschenberg’s work, it is the collage technique. While collage was initially developed in the 1920s by Dada artists such as Kurt Schwitters, Rauschenberg catapulted collage into the sphere of ‘hyper collage’.[5] Rauschenberg’s work contains layered image sequences, or image sentences, where the viewer interprets the progression of images as though reading a language system. Rauschenberg’s syntax, however, is arranged in multiple, simultaneous combinations and directions. It demands a different kind of looking – a repetitive change of focus, back and forth, in an analysis of the detail of each individual component image in order to perceive the composition as a whole. While this fragmentation of the composition is akin to the multiple viewpoints of Cubism, it has been more eloquently compared by John Cage to watching ‘many television sets working simultaneously all tuned in differently …’ [6]

Rauschenberg’s series of dense collage works, Horsefeathers thirteen, is a striking example of the artist’s innate talent in constructing compositions of detailed sophistication. Mass media action images, such as running races, horse-riding and rowing, are mixed with more generalised subjects that blend the natural environment with the manufactured environment. Each image is poised on the precarious dynamic moment and, in this way, Rauschenberg succeeds in investing his works with a simultaneous sense of movement and suspense. There is no hierarchy of images – the path of visual exploration for each composition is of our own choosing, despite the occasional (and humorous) directional arrow. The Horsefeathers thirteen series is a visual experiment in the ‘random order’ of experience. [7] By presenting us with a series of signs that encourage multiple complex readings, the artist has attempted a collaboration with the specific memories, associations and thought processes of the individual viewer.

While the images and objects selected for inclusion within the artist’s compositions may not be personally symbolic, they do reveal much about the American social events and political issues of the cultural period in which they were created. The garishly coloured Reels (B + C) series appropriates film stills from the 1967 Bonnie and Clyde movie, starring Faye Dunaway and Warren Beatty, and exposes Rauschenberg’s fascination with celebrity and the entertainment industry. In a similar fashion, the photo-collage work Signs operates as a succinct visual summary of the cultural and political events of the 1960s, depicting the tragic musician Janis Joplin, the assassination of John F Kennedy, America’s race riots and the Vietnam War. Rauschenberg has always been an artist-activist, skilled in employing art to raise individual awareness of social, environmental and political issues.

Rauschenberg’s work from the 1950s and 1960s can also be seen as a presentation of the street culture of the urban environment. During this period, Rauschenberg lived in New York and regularly walked the streets in order to collect the ‘surprises’ that the city had left for him. Many of these found objects were incorporated into his artwork, the most famous of which is a stuffed goat (Monogram 1953–59). The Gallery’s Albino cactus (scale) with its combination of two-dimensional photographic imagery and three-dimensional found objects can be considered a late ‘Combine’ work.

A ‘found’ tyre in Albino cactus (scale) is incorporated into Rauschenberg’s artistic expression, but it cannot be completely detached from its life spirit. The Duchampian displacement of the found object from life, and its subsequent transference to art, creates something akin to a split personality; that is, all found objects bring with them a history and/or pre-function which the artist allows to seep into the composition. Thus, in a collaborative encounter with his material, Rauschenberg becomes a choreographer of the historical meaning and value of the found object.

The images collaged along the material panel backdrop of Albino cactus (scale) have been printed via a solvent-transfer process – a technique that Rauschenberg began to experiment with in 1959. However, the look of Albino cactus (scale) also recalls Rauschenberg’s many screenprinted paintings, first explored by the artist in 1962. (It was at the same time that Andy Warhol also adopted the screenprinting technique and the two artists traded ideas about the method.) The solvent-transfer process and screenprinting technique liberated Rauschenberg’s work. With both forms of printmaking, the artist discovered ways in which he could quickly and repetitively transfer his found imagery to the canvas of his paintings and Combines.

Rauschenberg believed that the printmaking technique of lithography was old-fashioned and is notorious for having stated that ‘the second half of the twentieth century is no time to start writing on rocks’. Ironically, it is Rauschenberg who became a significant figure in the resurrection of American printmaking that occurred during the 1960s. He has subsequently worked with many leading print workshops to create more than 800 published editions. Printmaking is a technique perfectly suited to his methodology of layering found images and one which gave him total control over the size and scale of each component image. It was through printmaking that Rauschenberg was able to once again blur the distinctions between media and perfectly unite his obsessive use of the photographic image with painterly techniques.

One of the most successful of Rauschenberg’s collaborations has been with the Gemini GEL print workshop – a printmaking partnership that permanently changed the terrain of American printmaking. The artist’s highly experimental approach to print processes comes to the fore in the colour lithograph and screenprint Booster, created in 1967. For Booster, Rauschenberg decided to use a life-sized X-ray portrait of himself combined with an astrological chart, magazine images of athletes, the image of a chair and the images of two power drills. Printer Kenneth Tyler was a masterful facilitator for Rauschenberg’s ambitious project and the collaboration radically altered the aesthetic possibilities of planographic printmaking. Rauschenberg and Tyler pushed beyond what had previously been done by combining lithography and screenprinting in a new type of ‘hybrid’ print. The rules governing the size of lithographic printmaking were also ignored, and at the time of its creation Booster stood as the largest and most technically sophisticated print ever produced. Today, Booster remains one of the most significant prints of the twentieth century, a watershed that catapulted printmaking into a new era of experimentation.

In 1969 Rauschenberg was invited by NASA to witness one of the most significant social events of the decade – the launch of Apollo 11, the shuttle that would place man on the moon. NASA also provided the artist with detailed scientific maps, charts and photographs of the launch, which formed the basis of the Stoned moon series – 30 lithographs printed at Gemini GEL. In the transference of the found images to the stone, Rauschenberg had the stones photosensitised, while vigorously applied lithographic crayon and tusche were used to create lines of motion. Once again, we find a mix of the mechanical and the gestural, a juxtaposition of the mechanically reproduced photographic image and the handcrafted ‘television static’ appearance of Rauschenberg’s painterly and drawn additions. The Stoned moon series of prints is a celebration of man’s peaceful exploration of space as a ‘responsive, responsible collaboration between man and technology’.[8] Furthermore, the combination of art and science is something that Rauschenberg continued to pursue throughout the 60s in what he calls his ‘blowing fuses period’.

Rauschenberg’s collaborations with printmakers and print workshops have often not resembled traditional prints at all. In his typical mix of techniques and processes, the artist has radically re-interpreted the traditional notion of what constitutes a print. Seizing upon the notion of multiplicity, inherent in the printed form, Rauschenberg has frequently applied it to sculpture to create multiple sculptural works that are editioned, just as a traditional print can be editioned. His three-dimensional Publicon station multiples are seven physical expressions of the clash of art and religion and a reference to Christ’s 14 stations of the cross. Early in his life Rauschenberg was very involved in the church and wanted to become a preacher. His decision was reversed, however, when he was told that the church would not tolerate dancing (an activity that Rauschenberg was particularly good at). Just like this clash of religion and culture in life, the Publicon stations represent a similar clash of visual elements in art. They are austere containers that unfold to display intricately collaged, bright fabrics and electrical components. Akin to the individual steps that make up a choreographed dance, the works are adjustable through various configurations. As box-like containers, the Publicon stations also reveal the influence of Marcel Duchamp and Joseph Cornell. Rauschenberg closely studied the works of the two masters and repetitively referenced them in his own work.

A fundamental shift in subject and material occurred in Rauschenberg’s work from the 1960s to the 1970s. In the 1960s he relied heavily upon American visual culture, whereas in the 1970s Rauschenberg embraced an international perspective. The works from the 1970s also reflect his incessant experimentation with new materials. Where the 1960s were dominated by repetitive mass media imagery, the 1970s reveal a focus on natural fibres, a simplification of the artist’s materials to incorporate fabric, cardboard and other natural elements such as mud, rope and handmade paper. The catalyst for this dramatic change in both subject matter and material can be explained by a change in Rauschenberg’s physical environment – his decision to move from New York City to Captiva Island, Florida, had a profound effect on the appearance of his work.

With no city to offer up its detritus, the artist turned to the things that surrounded him in his new environment and the move had yielded numerous cardboard boxes. Rauschenberg has suggested that his choice of cardboard as a new material was the result of ‘a desire … to work in a material of waste and softness. Something yielding with its only message a collection of lines imprinted like a friendly joke. A silent discussion of their historyexposed by their new shapes’. [9] The Cardbird series of 1971 is a tongue-in-cheek visual joke, a printed mimic of cardboard constructions. The labour intensive process involved in the creation of the series remains invisible to the viewer – the artist created a prototype cardboard construction which was then photographed and the image transferred to a lithographic press and printed before a final lamination onto cardboard backing. The extreme complexity of construction belies the banality of the series and, in this way, Rauschenberg references both Pop’s Brillo boxes by Andy Warhol and Minimalist boxes such as those by Donald Judd. By selecting the most mundane of materials, Rauschenberg once again succeeds in a glamorous makeover of the most ordinary of objects. This is an exploration of a new order of materials, a radical scrambling of the material hierarchy of modernism.

During the 1970s, Rauschenberg’s new international focus required him to travel to several countries where he entered into significant collaborations with local artists and craftspeople. The first was in 1973 with the medieval paper mill Richard de Bas in Ambert, France. Once again, Rauschenberg imposed a disciplined stripping back of his art materials – this time it was not to do with colour but with the notion of the handmade. In particular, the artist wanted to engage with handmade paper as one of the most ancient of artistic traditions. The resulting series, Pages and fuses, is a group of paper pulp works where the Pages are formed from natural pulp and shaped into paper pieces that incorporate twine or scraps of fabric. In contrast, the Fuses are vivid pulp pieces dyed with bright pigments. It was precisely this innovative experiment with paper pulp that sparked a renewed interest in handmade paper, which inspired major paper works by artists such as Ellsworth Kelly, David Hockney and Helen Frankenthaler.

Throughout his career, Rauschenberg worked with fabric in the creation of theatre costumes and stage sets. In 1974, however, his interest in the inherent properties of natural materials led him to experiment with the combination of fabric and printmaking. The Hoarfrost editions series, created at Gemini GEL, is named after the thin layer of ice that forms on cold surfaces and was inspired by Rauschenberg’s observation of printmakers using ‘large sheets of gauze … to wipe stones and presses … and hung about the room to dry … how they float in the air, veiling machinery, prints tacked to walls, furniture’. [10] The imagery of the Hoarfrost editions was drawn from the Sunday Los Angeles Times and printed onto layers of silk, muslin and cheesecloth. The artist exploited the transparent layering of material in order to suspend the image within the work itself, enabling the viewer to both look at and look through the work – to see both the positive space and the negative space in conjunction with the environment behind the work. Everyday objects, such as paper bags, are in sophisticated contrast with the ghostly imprinted imagery and the folds and layers of the delicate fabric.

Rauschenberg’s quest for continued international involvement took him to Ahmadabad, India, to work in a paper mill that had been established as an ashram for untouchables. Rauschenberg was immediately struck by the contrast between the rich paper mill owners and the absolute poverty of the mill workers. The artist’s specific environment once again provided him with materials and in 1975 he set about making the Bones and unions series. For the Bones, the collaborative team wove strips of bamboo with handmade paper embedded with segments of brightly coloured Indian saris. In the creation of the Unions, Rauschenberg sought to incorporate the mud that was used by the villagers to build their homes. He achieved this by concocting a rag-mud mixture consisting of paper pulp, fenugreek powder, ground tamarind seed, chalk powder, gum powder and copper sulphate mixed with water, all of which was then kiln fired. For Rauschenberg, the striking contrast between the sensuous colour of the saris and the aromatic and earthy aesthetic of the rag-mud encapsulated the manifest social and cultural contrasts of India.

The rich textile area of Ahmadabad, India, also provided Rauschenberg with the inspiration for his Jammers series of 1975–79. Apparently, Rauschenberg ‘was very excited by what he saw there [in India] … rolling out bolts and bolts of sari material, each one more beautiful than last. He was feeling the texture, just amazed at the colours. A new sense of fabric came to him there’. [11] Reef (Jammer) is a minimal installation of five white sheets of silk, suspended by pins and elegantly draped to flutter in the breeze. While the work’s title is a nautical reference, Reef (Jammer) recalls the ‘hyper-sensitive’ receptor surface of Rauschenberg’s series of 1951 white paintings, which were sophisticated in their simplicity and functioning as ‘airports for the lights, shadows, and particles’. [12]

In all of his artistic pursuits, Rauschenberg has been an enthusiast for collaboration, working with numerous artists, composers, papermakers and printmakers. His joy in creating works of art within a reciprocal exchange has also extended to his materials. By looking beyond the apparent ordinariness of everyday experience, Rauschenberg celebrates the life spirit of all things, realising the unique qualities of everything from individual colours, mass media clippings, paper, fabric and mud to electric lightbulbs and old tyres. In this way, Rauschenberg has imbued his art with the visual ‘poetry of infinite possibilities’. [13]

Jaklyn Babington

Curator, International Prints and Drawings