Finding a new language

MARK SETRAKIAN and RICHARD TAYLOR discuss the use of sound in JORDAN WOLFSON's Body Sculpture.

Jordan Wolfson’s new work Body Sculpture premieres at the National Gallery in December. It was created in close collaboration with world-renowned robotics expert Mark Setrakian, who also worked with Wolfson on his previous animatronic works Female Figure 2014 and Colored Sculpture 2016.

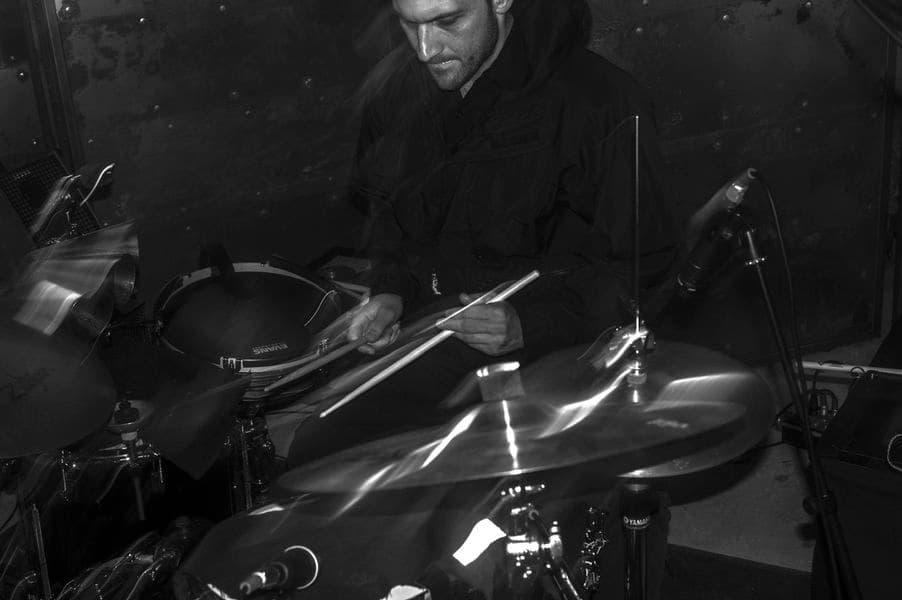

A central element of Body Sculpture is its innovative use of sound. In this conversation with his long-time friend and fellow special effects pioneer Richard Taylor, co-founder and creative lead at Wetā Workshop, Wellington, Setrakian shares on the creative and technical development of the sonic elements of Body Sculpture, including working with percussionist and composer Eli Keszler and the references and influences that helped shape the work.

This conversation was conducted over Zoom on 11 March 2023.

Richard Taylor, Wētā Workshop Unleashed, photograph: Wētā Workshop 2020 © Wētā Workshop

Richard Taylor: It would be nice, Mark, to ask you about the sound [from Body Sculpture] as you’ve created a sound with this character that is to me quite primitive.

When I say primitive, it took me straight to the hollow-log drumming of a Tongan ceremony. That extraordinary sound that comes from just wood striking on wood. But because of the expertise of hollowing out the log, the maker gets a certain guttural resonance out of it and I could feel that through the thickness of the aluminium skin that you’ve chosen and the surface treatment of the fingertips; you’ve created a resonance in the sound box, that is the body, that is very specific. And if it was pitched higher or lower or was more beautiful in its sound or cruder somehow, it wouldn’t have felt right.

Mark Setrakian: Jordan and I had a collaborator, a percussionist-composer named Eli Keszler. One of the first things that that we did was explore the tonal character of the cube. You get a very deep tone if you strike it a certain way towards the centre. And as you get towards the edge, you can find these very high ringing resonant tones. And so [Body Sculpture] is capable of drumming in different ways. It can use the palm of its hand but it can also tap with thefingertips. It can also hyperextend and strike the surface with not the plastic fingertips or the plastic palm, but the exposed metal portion of the servos.

So the range of tonality is quite great and there was a lot of time spent exploring that and discovering how to use it and making the rhythm more complex, pulling it back, making it more simple, working at the knife’s edge to get something that is strong and effective.

This cube also has rhythmic patterns. At one point in the drum scene, it’s playing a three-against- four pattern with one hand which I think is that log drum thing you’re talking about, a repeating four-note pattern and then a contra rhythm, a three-note pattern with the other hand. And it starts to fugue against itself. It’s very subtle, but when it’s played back on the main system, it’s very affecting.

The other thing about working in the final installation space is that we’re capitalising on the natural acoustics. When I’m standing far away from it, the sound echoes through the space and seems like it’s coming from something enormous. Then I’ll see Body Sculpture there drumming on its front face. It starts to slap first with one hand and then with two hands. And it gets more intense and then it gets even more intense. And if you watch carefully, you see it’s actually driving itself backwards with each strike. It has so much energy. Then the next thing is it breaks into this delicate rhythm just lightly tapping with a fingertip.

That was extremely challenging, making something capable of those very loud, powerful, violent hits and then a moment later precisely delivering these tiny inflections on the surface and on the top.

RT: Is the intent that the audience questions its gender because it has a very masculine, chest-thumping attitude, that you see in males, whether they be human or gorillas. Yet, it then has the ability to switch–and get down to what’s most subtle, beautiful, sensuous.

Because it has the ability to flex its fingers back and the ability to use its upper palm. It’s a feature you see in some performers who have trained themselves, to a very high degree, in the dexterity of their fingers for certain indigenous dance, tea ceremonies etc. You see it when certain guitarists have the ability to strum, pick and then use the acoustic drum-like quality of the body of the guitar in a beautiful way. Almost like flamenco guitarists.

MS: It really only has, as far as you know, the thickness of the material, the zone on which it strikes and then the velocity by which it strikes it.

RT: I even saw that you were rolling the hand slightly to get the timbre of the sound moving across certain parts of the palm. Not just relying on the roll of the fingers. A multifaceted movement to induce music out of that cube.

MS: I resorted to high-speed photography to analyse what is happening when the finger is striking the surface. There were a few moments that I really had to fine-tune and I shot them as slow motion.

Jordan Wolfson, Body Sculpture (detail), 2023, National Gallery of Australia Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2019 © Jordan Wolfson. Courtesy Gagosian, Sadie Coles HQ, and David Zwirner. Photo: David Sims.

RT: The analogy of the flamenco guitarist is a good one. I’m a fan of Rodrigo y Gabriela and they play their guitars like percussion instruments. And evoke all sorts of different sounds. I knew it was possible to get a wide range of sound out of a simple shape, a resonant body. It’s like a drum or a guitar.

MS: I had to talk with Eli, our percussionist, to establish what was possible with this robot. If I take the hand off the cube and hand this to you, it is really heavy. It’s 16 servos. It weighs about six pounds [2.7 kg]. Yet it looks very fluid and light in its motions. Creating those motions was a learning process. It was impossible for me to simply imitate what Eli was doing with his hands and his drumsticks. Could it be motion capture? No. The anatomy of the robot is too dissimilar from a human being.

What I arrived at were a whole library of gestures. They were a simulacrum of what a human would do passively on the surface of the drum, but what this cube is doing to invoke that was not based on human motion. It was a hundred percent robotic motion that gives us the impression that it’s moving the way a person would.

RT: At some point you went: should I try to replicate? or should I be induced through inspiration? Obviously what you’ve done is the second one. You’ve taken the best of the rhythm and movement and sound that can be created by the human hand then allowed the robotics, the mechanics to achieve more than the human hand can. So it’s finding a new sonic language.

MS: A new sound for the interface of the hand on the drum. One that’s unique and specific to this character. Working with Eli was a two-way educational process. I’m also a musician so Eli and I spoke the same language and it was very easy for us to talk about rhythm and about the nuances of flaming a strike or a tempo push or different musical terms that were applicable. But at the same time that I was learning how he would create specific drum tonalities on this surface, simultaneously, he was learning what the robot could do and how it did it.

Jordan was with us the whole time and was really interested in the visceral response to the experience of hearing this music. Where does the balance lie between having an intricate musical performance and a deeply affecting musical performance?

RT: I guess it is only possible if the roboticist is also the performance artist. And is attuned to the qualities of musical tone and human capability to draw unique things out of their instruments.

Jordan Wolfson: Body Sculpture is on display from 9 December 2023 until 28 April 2024.

This is an excerpt from publication Jordan Wolfson: Body Sculpture, published by the National Gallery to coincide with exhibition Jordan Wolfson: Body Sculpture.

This story was first published in The Annual 2023.