Artists' Artists: Masami Teraoka

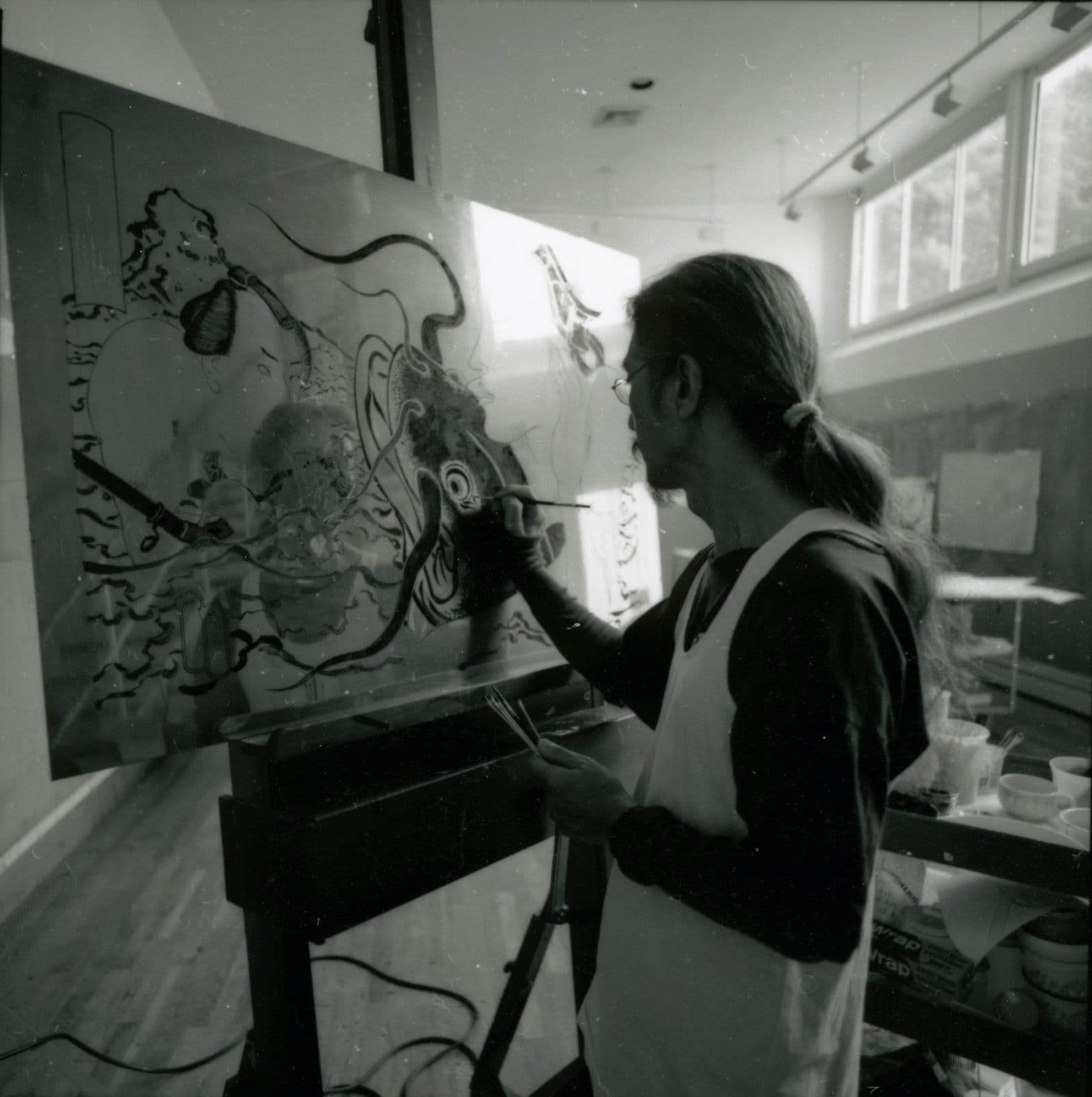

Masami Teraoka painting the etching plate for Catfish Envy from the Hawaii Snorkel Series, Tyler Graphics artists' studio, Mount Kisco, New York, 1991. Kenneth E Tyler Collection archive, NGA Study Collection © photographer, Marabeth Cohen-Tyler

Artist MASAMI TERAOKA discusses works of art from the national collection that inspire, move or intrigue him.

Masami Teraoka, printed and published by Tyler Graphics, Catfish Envy, 1993, from the Hawaii Snorkel Series, 1992–93, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased with the assistance of the Orde Poynton Fund 2002 © the artist and Kenneth E Tyler

MASAMI TERAOKA

born Japan, 1936

Catfish Envy 1993

Ken Tyler, my collaborating printer whose archives are held by the National Gallery, was very encouraging in allowing me to experiment on this print, Catfish Envy. Historic Japanese woodcuts are typically only half the size of this print, but Tyler was able to translate the image into etching plates, aquatint and woodcut so that we could create a more expansive image.

This composition, while erotic in nature, also draws on Japanese folklore and figures drawn from kabuki traditions. The main figure depicted is my friend Sarah, an American woman who grew up in Japan. A Japanese man, resembling a samurai, holds a snorkel and looks towards Sarah in the background. While he is a generic figure, his face and makeup identify him as a kabuki actor, a juxtaposition that creates tension between history and the present and between these figures who embody the East and the West. Sarah holds a catfish, an animal that appears often in historic woodblock prints. In Japanese folklore, there is a belief that catfish can detect earthquakes before they occur. The catfish is also often a stand-in for me; like the catfish in folklore, I believe that artists often anticipate cultural narratives and social issues before they become mainstream.

Utagawa Kunisada I, Ichikawa Ebizo V as Kumagai Naozane, 1852, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, gift of Dr Lee Kerr and Mark Henshaw 2015. Donated through the Australian Government's Cultural Gifts Program

UTAGAWA KUNISADA I

Japan, 1786–1865

Ichikawa Ebizo V as Kumagai Naozane 1852

Among the classic ukiyo-e artists, I think that Kunisada stands apart for his figuration. Other woodblock print artists often try to stylise the face so that their characters feel more universal or generic. Kunisada’s characters, however, feel like individuals and not archetypes; the line work is more subtle, and the compositions are quieter than in the work of Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, who was more interested in the drama or violence of the narrative that’s depicted. In this composition, the central character is modelled after the iconic kabuki actors of the Edo-era, but he is rendered with such expressiveness that we become drawn into his individual story.

Kunisada also uses cartouches and calligraphy in an interesting way that reminds us that his compositions do not depict reality — they reside in the world of art. Each cartouche also functions as a picture within a picture, adding another layer of meaning and complexity to the image.

Claes Oldenburg, Ice bag - scale B, 1971, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1975 © Claes Oldenburg and Coosje Van Bruggen

CLAES OLDENBURG

Sweden, 1929–2022

Ice bag – scale b 1971

I met Claes Oldenburg when he was working with the fine-art press Gemini G.E.L. Ken Tyler was at the press in those days and I remember meeting Ken in this period in Los Angeles. At that time, Oldenburg was creating his iconic ice-cream cone drawings and prints, which were later realised as sculptures. My friend, who was a photographer, worked for Gemini G.E.L. and had a studio next to the press. He invited me to have an exhibition in his studio, which was open to the public but under the radar. I showed my own drawings and watercolours of ice-cream cones and a series that I called Banana girls, which were psychedelic drawings of women licking peeled bananas. Oldenburg saw my show several times when he worked next door with Gemini — I think he was looking closely at my ice-cream cone drawings too! I like the surprise in Oldenburg’s work, and how he took commonplace objects like ice bags and made them both strange and humorous. I also appreciated how he was very experimental and always created work that was unexpected and sometimes funky, but always beautiful. He was conceptually driven, but always considered aesthetics in creating his work.

When I began my career, I had a very narrow and traditional idea of what it meant to be an artist, particularly as it related to painting. As a young man, I had a very close affiliation with the Gutai Art Association in Japan and played jazz with several artists who were also part of the movement. The core concept of the Gutai was that artists should be free and can use any kind of material to realise their artistic vision. I saw Oldenburg’s work as a continuation of this spirit of the Gutai and admired his uncompromised commitment to his expression.

Anselm Kiefer, Abendland [Twilight of the West], 1989, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1989

ANSELM KIEFER

Germany, born 1945

Abendland (Twilight of the West) 1989

The earliest works of Anselm Kiefer that I saw resembled ruined cities; they felt like they blurred the lines between painting and sculpture, mixing materials like oil paint with cement. His compositions have a particular strength in that they are both beautiful and chaotic. The railroad tracks in this painting, Abendland (Twilight of the West), appear to lead to a concentration camp, but the landscape behind it is both defined and abstract — Kiefer creates a picture that has a looseness to it, and this looseness has an emotional power to it. There is also an intense physical quality to Kiefer’s work, especially in his thick surfaces and build-up of materials. His subject matter is messy and violent, but he uses aesthetics to find a poetry that draws the viewer in and invites reflection on tough subjects. This is a tension that I want to evoke in my recent work which similarly depicts cities ruined by war.

This story was first published in The Annual 2023.