Come Together

Nan Goldin, Twisting at my birthday party, New York City, 1980, 1980, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2021 in celebration of the National Gallery of Australia's 40th anniversary, 2022 © Nan Goldin

ANNE O’HEHIR discusses the evolution of NAN GOLDIN’s portrait of her community, The ballad of sexual dependency.

When she arrived in New York in 1978, Nan Goldin became a part of a vibrant, unruly community made up of artists, actors, filmmakers, musicians, writers. Gritty. Pre-gentrification. They saw themselves as heirs to the freewheeling sexually-fluid days of Weimar Germany, in punky rebellion against the conservatism and values of mainstream America. Goldin lived by night, working in bars, taking drugs, falling in and out of love, making ends meet. She had studied photography in Boston and to this community, her community — congregating in the Bowery, the cheap, rundown neighbourhood in the Lower East Side — she brought a commitment to documenting her life and those around her as honestly as she could.

'There's a glass wall between people and I want to break it.'

Her camera accompanied her everywhere. Lacking access to a darkroom, Goldin had shown her work at art school by projecting slides and now she started showing the photographs she was taking, arranged into themes and performed as slideshows in underground clubs and projection spaces. This ever-shifting, ever-evolving study of her life would coalesce in time into The ballad of sexual dependency. The people in the audience were the people in the images. The slideshow was a gift to her community. Her intent for those she cared about — she had to feel a connection for the image to work, the work like ‘a caress’2 — to see themselves as she saw them, as beautiful.

Each showing was much anticipated; it didn’t take long for word to get out and for Goldin’s audience to expand as The ballad began to be included in museum shows. In 1985, the slideshow was shown at the Whitney Biennial and the following year the Aperture Foundation published The ballad as a photobook comprised of a selection of 126 images from the 700 or so that made up the slideshow. The images chosen for the book were also printed as a suite of Cibachrome prints in an edition of ten. The National Gallery acquired the last set in the edition in October 2021 from Goldin’s personal collection. Intensely saturated, glossy, almost impossibly seductive prints; pulsating, as the projected slides had with light, as if lit within.

Nan Goldin, C.Z. and Max on the beach, Truro, Mass., 1976, 1976, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2021 in celebration of the National Gallery of Australia's 40th anniversary, 2022 © Nan Goldin

Two days before we began installing The ballad in June 2023, I attended a panel discussion made up of the judges of the National Photographic Portrait Prize. They were asked to describe the attributes they were looking for in choosing the finalists and all were in agreement. The closer, more meaningful and more clearly discernible the connection between the photographer and the subject the more successful the portrait. Admittedly, Goldin was on my mind; but as I sat there listening, I could not help but reflect that this way of defining portraiture, accepted and expected, owed as much to Goldin and her far-reaching impact on the photographic scene up to today as to anyone. She explained: ‘The pictures come out of relationships, not observation.’3

'So many great portraits come from a place of vulnerability.'

I thought back to so many extraordinary canonical photographers who through either intent or shyness had rather diffident or oblique, indeed often non-existent relationships with their subjects — Walker Evans, Robert Frank, Helen Levitt, Paul Strand. The camera gave them a reason to be somewhere but then an excuse not to get too involved. ‘I don’t quite mean they’re my best friends’, American photographer Diane Arbus famously clarified in the remarks preceding those extraordinary portraits in her Aperture monograph, ‘I don’t mean in my private life I want to kiss you’.4 Arbus thought the people she photographed were terrific, as she thought many things, but she wanted us to know that she wasn’t like them. Not really.

Nan Goldin, Nan and Brian in bed, NYC, 1983, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1994 © Nan Goldin

Arbus brought complicity and time into the photographic exchange in a way that was revolutionary. She interacted with her subjects and famously outstayed her welcome when her forensic eye alighted upon someone who interested her. But the more she stayed the more uncomfortable and increasingly suspicious they became. Working a decade behind Arbus, Goldin also photographed people, sometimes not over hours but over decades. And yet her approach is built on an entirely different premise. These really were her best friends and her lovers, the family she chose, what she described as her ‘tribe’.

She was all in. She regarded the camera as an extension of her hand, and this merging of body and her creativity gives her photographs an altogether haptic, sensual intimacy and intensity. Great artists and writers possess an almost mystical ability to evoke their way of seeing and understanding the world and to invite us to join them in that world. Goldin does this intuitively. She doesn’t see very well and perceives the world in hazy blocks of colour. Her use of blurry focus and veils of colour pull us in. It’s as if the emotion has bled across the surface of the image. Her snap-shot aesthetic makes her compositions casual and immediate: with people and things falling out of the frame, the presence of lens flare and heavy shadows thrown by the flash. It’s as if we, too, have just stumbled upon these scenes. No one does it quite like Goldin.

Nan Goldin, Cookie with Max in the hammock, Provincetown, Mass,. 1977, 1977, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2021 in celebration of the National Gallery of Australia's 40th anniversary, 2022 © Nan Goldin

Nan Goldin, Cookie and Vittorio's wedding, New York City, 1986, 1986, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2021 in celebration of the National Gallery of Australia's 40th anniversary, 2022 © Nan Goldin

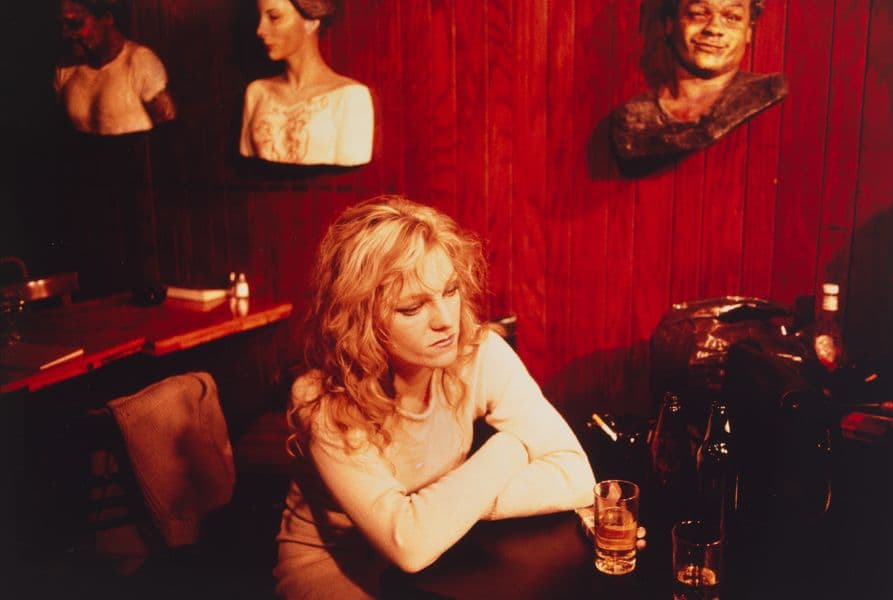

Nan Goldin, Cookie at Tin Pan Alley, New York City, 1983, 1983, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2021 in celebration of the National Gallery of Australia's 40th anniversary, 2022 © Nan Goldin

Goldin often refers to the people in her images as her superstars and it is how I have come to think about them as well: ‘they become’, she has stated, ‘a star in the movie of my life’.5 Some of them have achieved a cult following without Goldin; Cookie Mueller, queen of the Lower East Side, author, performer, actor and Dreamlander, is the most obvious person in this regard. But others, like Suzanne Fletcher, a minor actor who reappears throughout The ballad an astonishing 11 times — just shy of Goldin’s boyfriend Brian Burchill’s 14 appearances — is a ‘superstar’ because of Goldin and the love between them. They are two women whose friendship went right back to high school, back to before Goldin picked up a camera. Back to when Goldin turned up still bereaved and silent, following the suicide of her beloved older sister three years earlier. Such closeness results in some of the most affecting, the most moving images in The ballad.

So many great portraits come from a place of vulnerability. People you sense guarding their souls from the merciless dispassionate stare of the camera. The camera could be ‘a little bit cold, a little bit harsh’,6 Arbus also remarked, and it was in her hands. It is what a lot of us experience in front of the camera, I suspect, a fear of being manipulated in some way, of being caught out.

Nan Goldin, Brian with the Flintstones, New York City, 1981, 1981, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2021 in celebration of the National Gallery of Australia's 40th anniversary, 2022 © Nan Goldin

Because of the trust that Goldin was able to build — gaining access to her friend’s bedrooms and bathrooms and private moments on the toilet or having sex — we see her friends in moments of great openness where performance falls away. We see Suzanne travelling with Goldin, off to Berlin or Mexico, in her parents’ house, in her parents’ bed. Lost in passionate, all-consuming embrace with her boyfriend of the time, in the shower, found staring at herself in mirrors and (for me the most emotionally raw image in The ballad ) crying. It’s a supreme moment of courage and connection. At the time this level of disclosure and self-disclosure was exceptional in photography.

Nan Goldin, Suzanne with Mona Lisa, Mexico City, 1981, 1981, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2021 in celebration of the National Gallery of Australia's 40th anniversary, 2022 © Nan Goldin

Nan Goldin, Suzanne in the green bathroom, Pergamon Museum, East Berlin, 1984, 1984, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2021 in celebration of the National Gallery of Australia's 40th anniversary, 2022 © Nan Goldin

Nan Goldin, Suzanne crying, New York City, 1985, 1985, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2021 in celebration of the National Gallery of Australia's 40th anniversary, 2022 © Nan Goldin

The privileging of friendships and a recognition of the vital role that it plays in our lives is what makes The ballad a call to arms at a time when societal convention saw the nuclear family and romantic love and marriage as the path to happiness. It is what made it radical in its time and perhaps why it continues to engage and move us. As Goldin has said, the one good shrink she went to told her that she had only survived because by the age of four her friends were more important to her than her family.7 As she makes very clear: ‘They’re the most important to me in the world, my friends. More important than family, lovers, my career.’8

Goldin’s commitment to caring for her friends and her community is one that has remained consistent, at the very heart of her practice and life. Perhaps in humanist terms, Goldin’s greatest achievement, her almost magical attribute, is her ability to bring people together to see themselves as a community and see the power that comes with that recognition. Through the way The ballad unfolds, she draws us into this space — one where Goldin’s love and empathy for those she photographs is palpable. The images become collaborative and audacious acts of generosity on both the part of the photographer and the subject.

Nan Goldin's The ballad of sexual dependency is on display from 8 July 2023 to 28 January 2024 and touring to the Art Gallery of Ballarat 2 March to 2 June 2024, as part of Photo 2024.

This story was first published in The Annual 2023.