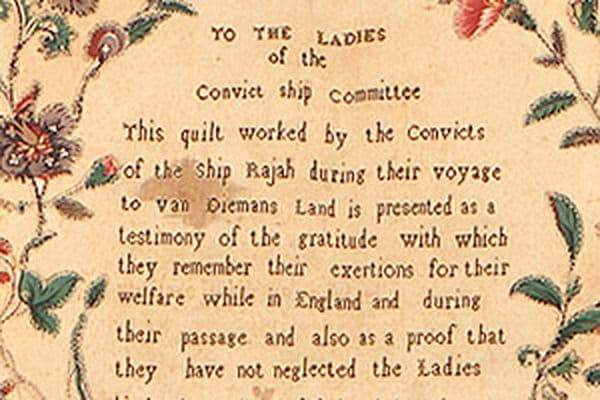

Noble skills, handsome silks: Behind Amy Susanna Staniforth’s Table cover c 1860

Amy S. Staniforth, Table cover, c.1860 (detail), pieced medallion style with hexagon and tumbling block pattern: silk and cotton satin, brocade, velvet, damask, taffeta and ikat, silk ribbon, linen (backing), cotton thread; hand appliquéd, hand embroidered, hand stitched, 160 h cm, 117.6 w cm, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2002

ALICE REZENDE explores the work and ethos of industrious early settler quilter and educator Amy Susanna Staniforth.

Britain! dear Britain! country of my birth!

Where maply valour, honest worth and truth,

Dwell in the bosom of ingenuous youth!

Where modest maiden, daughter, sister and wife,

Embellish homes, the pride of manhood’s life!

AMY STANIFORTH1

From her emigration to Australia with five of her adult children in the early 1850s, Amy Susanna Staniforth (1792–1868) was chiefly preoccupied with the instruction of ‘young minds to virtue’ 2 and, in particular, that of young women. An educator and devout Protestant, Staniforth had also likely served as an officer in the 44th Regiment.3 It was during this brief posting that she may have met her late husband William Staniforth (1788–1835), a prominent surgeon of the Sheffield Infirmary. A by-product of the Industrial Revolution, her social circumstances illustrate a burgeoning English and European middle-class, where ‘gentle’, educated women could now pursue jobs outside the home while nonetheless being expected to manage its inhabitants, interiors and effects.

Staniforth’s only known quilt, Table cover c 1860, lies at the intersection of multiple stories taking place in nineteenth-century Australia, England and Europe. It not only speaks of Staniforth’s character and values as a dedicated educator and mother, but also of the development of Western textile colour technologies, the silk and patchworking fashions of the time and the economic role of women of ‘proper education’ in colonial English settlements such as Australia.

From her arrival until perhaps as late as 1858, Staniforth worked as a teacher and headmistress in girls schools, taking over the running of Ariel Cottage in Redfern on Gadigal land in New South Wales in 1853 alongside her three adult daughters and ‘assisted by a resident French governess and the first masters in the colony.’ 4 An advertisement for the school of the same year notes ‘young women may attend in a drawing and painting class from private families without being pupils in any other way … Private lessons in music also.’ 5 This reflects the prime importance of fine art skills to the moral and social development of middle-class women. With an increasing amount of time to spare and households partly run by servants, there was growing anxiety that women could develop ‘improper propensities’ such as ‘a taste for luxury and idleness, which is known to have so baneful an influence on the strength, the population, and the prosperity, of a nation.’ 6

It comes as no surprise then, that domestic advice and household manuals were incredibly popular with women of Staniforth’s class and standing, both in English-speaking Europe and the English colonies. Many manuals, such as The Female Instructor (1815) and Cassell’s Household Guide (c 1870), survive in Australian archives and museum collections7 and demonstrate the cultural pervasiveness and influence they had on women’s psyches. Describing in great depth how to run an efficient home, these manuals more importantly detailed the virtuous traits, skills and activities required of model wives, mothers and daughters.

'The work which is here presented is calculated to unite, in the female character, cultivation of talents, and habits of economy and usefulness; particularly domestic habits. These, it will be readily acknowledged, are essential. The woman who possesses not these qualifications, whatever else she may possess, will never fulfill, either with credit to herself, or with satisfaction to others, the important duties of a daughter, a wife, a mother, or a mistress of a family.'

THE FEMALE INSTRUCTOR8

The Female Instructor, 1815, frontispiece, public domain.

https://archive.org/details/b21532217/page/n5/mode/2up

Employed in the education of young ladies, it is highly likely Staniforth consumed and even promoted the readings of these household manuals. Staniforth’s largely autobiographical poetry volume, Australia and other poems (1863), demonstrates how closely her moral and religious values aligned with this material. Among the domestic skills encouraged in the manuals was, of course, needlework. Quilt-making, patchwork and embroidery were taught to most girls during this time, whether at home or in schools.

'The advantages of making patchwork, besides the useful purposes it is put to—and, indeed, to be reckoned before those purposes—are its moral effects. Leisure must either be filled up by expensive amusements, “mischief,” or by listless idleness, unless some harmless useful occupation is substituted. Patchwork is, moreover, useful as an encourager of perfection in plain work, because it must be very neatly sewn, especially if made of silk pieces and sewn with white sewing silk. The ordinary sewing is used, and the ordinary running to quilt it. So patchwork often plays a noble part, while needlework is encouraged and brought to perfection, and idle time is advantageously occupied.'

CASSELL’S HOUSEHOLD GUIDE9

Early quilt designs featuring the tumbling block pattern, employed to great effect in Staniforth’s Table cover, are found in examples from Great Britain and Europe in the 1830s and 1840s, while in Australia the earliest known mention of the pattern is 1844.10 Since fabrics and needlework materials were largely imported from Britain at the time, it was fashionable for women to also replicate the latest design trends. The tumbling block or baby block pattern proved a useful patchwork style to teach to beginners. Not only were diamond and hexagon shapes simpler and easier to stitch together from a paper template, they could also be cut from cheaper and more widely available printed cotton dress fabrics, which featured small repeating patterns, thus ensuring a successful all-over design.

Australian quilt historian Margaret Rolfe has pinpointed how Staniforth’s Table cover bears a remarkable resemblance to a patchwork design for a ‘counterpane or table cover’ described in Cassell’s Household Guide, Volume 1.11 Suggesting how to produce a particular patchwork pattern, the manual notes that it ‘would make a beautiful piece of fancy work in purchased materials of silk or satin’ in contrasting colours such as violet, light gold, crimson red, azure, and a deep-coloured ‘candlelight green’ which should be procured in silk, for ‘greens in wool are all dull.’ 12

'Patchwork made of pieces of silk and satin is handsome, especially if arranged with taste; and may be used for quilts, sofa and chair covers, cushions, and ottomans. Patchwork quilts allow of [sic] great exercise of taste.'

CASSELL’S HOUSEHOLD GUIDE13

Indeed, the most significant feature of Staniforth’s Table cover is its brightly coloured silks. The sheer variety of colours in this piece demonstrates the technological advancements of the textile dyeing processes, a field led by Britain following the turn towards industrial manufacturing. First discovered in 1856, chemical aniline dyes proved particularly effective when applied to weighted silks, and soon many new exciting colours and pattern combinations were developed. In the middle of the century, interior furnishing in silk fabrics thus became hugely popular: their threads were spun in various reliefs such as damask and brocatelle and in designs featuring roses and other flowers arranged in medallions or in motifs imitating architectural Rococo scrolls.14 Patchwork patterns like the tumbling block or baby block were excellent for showcasing the brightness, variety and technological skill evident in these new silks.

Amy S. Staniforth, Table cover, c.1860, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2002

Staniforth’s Table cover is an outstanding example of a combination of these historically fashionable fabrics, including silk and cotton satins, brocades, velvets, silk ribbons and silk damasks — their tasteful arrangement denoting Staniforth’s status in keeping up with the latest European Rococo revival interior design trends. Particularly effective is the use of black silk damask as a contrast ground to the luminous golds, violets, blues, reds, greens and the variously chequered and striped pieces. It is clear Staniforth took pride in her needlework and what her home furnishings inferred about her social status. Following a turn for the worse in 1854, a year after taking the running of the school in Ariel Cottage, Staniforth declared insolvency and many of her household items were listed to be sold via public auction. The newspaper notice paints a picture of her many effects:

'MR. RISHWORTH has received instructions to sell by public Auction, at Messrs. Mort and Co.'s Rooms, Pitt-street, on Monday, 3rd July, at 11 o'clock, the whole of the valuable Household Furniture and effects, comprising: —

Loo and dining tables; ottomans, cane-seated chairs; carpets, hearthrugs; curtains, poles, […] fenders and fire-irons; four post and French bedsteads; washstands and dressing tables; chest drawers; towel horses; dressing glasses; kitchen dressers and shelves; kitchen utensils, […] table and bed linen; square pianoforte; also, silver plate, plated ware, gold watch and chain […]. Terms—cash.' 15

While it is unclear whether Staniforth had begun to make her table cover during such a tumultuous time, the full chain of provenance of the item documents that it was passed down through many generations of the Staniforth family until it was acquired by the National Gallery in 2002. Layered in meaning, it is evident it has always been regarded as a precious heirloom. As research on the quilt continues to unfold, so does our understanding of the rich history of Australian quilts and their makers.

A Century of Quilts is on display from 16 March – 25 August 2024.