Jordan Wolfson

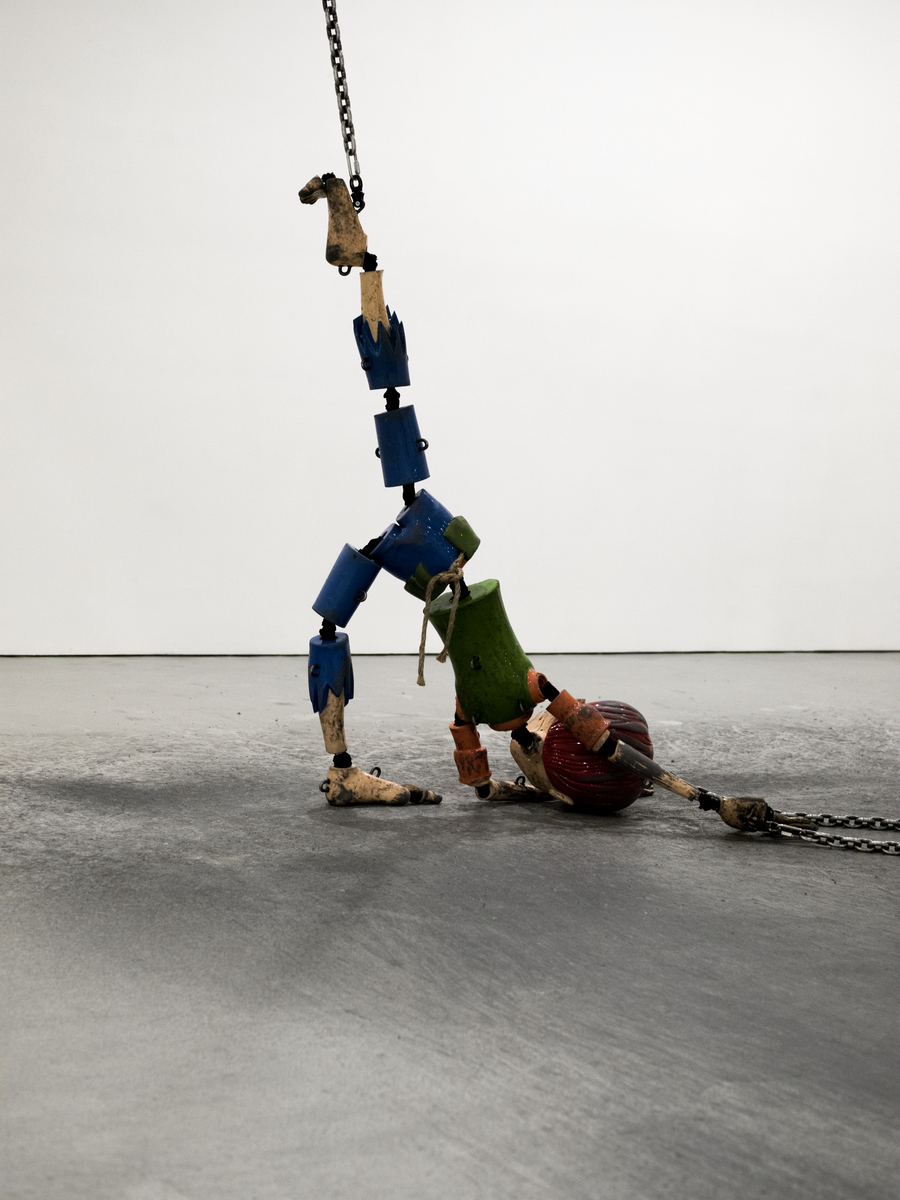

Jordan Wolfson, Body Sculpture (detail), 2023, National Gallery of Australia Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2019 © Jordan Wolfson. Photo: David Sims.

Ahead of the unveiling of his new work Body Sculpture, VAULT spoke to JORDAN WOLFSON about consciousness, Buddhist mindfulness and the positives of AI.

Jordan Wolfson wants you to like him, and well, it’s not difficult. He’s an excellent conversationalist, deeply curious, fastidious, ambitious and thoughtful. He takes time to formulate his answers. He thinks deeply. One of the most fascinating and provocative artists of his generation, Wolfson is ultimately preoccupied with what it means to be human, as explored through works of striking complexity and technological brilliance.

Ahead of the unveiling of his new work Body Sculpture 2023 VAULT spoke to Wolfson about consciousness, Buddhist mindfulness and the positives of AI. Body Sculpture will be shown alongside works selected by Wolfson from the National Gallery of Australia collection, offering audiences further insight into the artist’s innovative vision.

Jordan Wolfson, Colored sculpture (installation view), 2016, image courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner Gallery and Sadie Coles HQ © Jordan Wolfson, photograph: Dan Bradic

Are you going to be at the National Gallery when Body Sculpture is unpacked and at what point do you finish and hand it over? How do you know when to stop?

The artwork will be installed more or less without me. And then I’ll arrive probably in the middle of November, and I’ll work on this group exhibition from the collection. And then I have a little bit of polishing to do on the sculpture itself. And then I will work on the choreography of the viewership of the sculpture. And then I’ll oversee the exhibition probably a week after the show opens to the public to make sure everything’s running smoothly.

How many things are you working on at any one time aside from this work?

I was able to have a few side projects but as the completion date came closer and closer, I cut out all distractions. I can’t work on more than one thing at a time so when I do split up the time I’ll section off days or half days and jump between different tasks. With Body Sculpture, initially there was a lot of delay and waiting so I was able to produce other work, and even shows, while the vendors and fabricators were busy. When we got close to completion, I was still able to work on other things and I’d be called in to look at stuff. At the very end though, I cut out all the other work almost ritualistically to just focus on Body Sculpture, but somehow that wasn’t completely productive because it created a lot of nervous energy and gaps of nothing to do while I waited for the technicians to be ready for me.

How do you arrive at new ideas or new work?

I don’t actually get new ideas while I’m working on a big project like this, which I’ve always found strange. It’s like my mind is closed. I heard David Lynch talk, and he said the desire for an idea is like an invitation for the idea to come, so when I’m busy with a work, particularly at this scale, new ideas aren’t welcome and I’m only really creative in relation to the work in front of me. There aren’t sudden drops or downloads of new ideas.

Probably your brain is full while you’re working on something.

Yes, I’m not open to any new ideas unless those new ideas relate to what’s in front of me, pertain to my focus.

And then I guess with something like this, which is different again to the other sculptural iterations, the technology is extreme. Can you talk a little bit about that process? Is it sort of superseding itself as you are doing it?

In the case of this sculpture, we had the technology from 2020 up until 2023. It hasn’t changed that much, but we’ve written a lot of software to support the choreography. This work is pretty sophisticated and a lot of what I wanted wasn’t possible and a lot of what I thought would work formally didn’t. But I wasn’t disappointed, just forced to veer in different directions constantly and sometimes I thought I’d be sad but actually I was relieved when things failed, or sort of tickled by it, because you think you’re having a battle with technology, but you’re really just having a straightforward dance with art which is totally classical and formal and the same as with any other artwork. The illusion is that it’s different because of the technology, but it’s not. That was the lesson that knock me over the head.

Jordan Wolfson, ARTISTS FRIENDS RACISTS, 2020, image courtesy Jordan Wolfson Studio, Sadie Coles HQ, Gagosian Gallery and David Zwirner Gallery © Jordan Wolfson, photographer: Jack Hems

Jordan Wolfson, ARTISTS FRIENDS RACISTS, 2020, image courtesy Jordan Wolfson Studio, Sadie Coles HQ, Gagosian Gallery and David Zwirner Gallery © Jordan Wolfson, photographer: Jack Hems

It's that interesting thing about when you drive by a new car and then you drive it off a lot and it’s almost immediately redundant, it’s already lost its value – which is not to suggest your sculpture has. But that thing about putting something in place with all this technology but it’s changing so quickly. Will it have the opportunity to grow and change as a sculpture? To upload its technology, as it were?

I don’t know. Potentially yes, I think so. It’ll need to have that. But I’m mostly just consumed with the present moment, which is probably a little selfish and unprofessional of me.

No, I think that’s interesting. Anything to do with technology is so rapid.

If someone said to me, would you be worried about no one remembering your art after you’re dead…

I was going to ask you that question.

Well, the answer is no, I’m not concerned with that.

Why? Because you will be dead?

No, because that’s ego. It’s just silly and kind of laughable. I want to enjoy myself right now. Also the future is bright and there will be 3D printers running on AI that will help me print any part of this sculpture in the future.

Obviously, your work is very experiential. I read something where it was described as ‘event art’, which I thought was just about the worst phrase you could use to describe anything. But it does have an interactive element. Can you talk a little bit about that performative aspect?

Sure. I actually don’t like interactivity. I think there’s a part of our brain that’s for listening to music and looking at art. And there’s something about those two activities where the viewer becomes passive. There is another part of us that tells us to perform or serve others. I find that we switch between these roles. For whatever reason, I’ve found that interactivity shuts down this passive side in the viewer and they become stimulated in a pragmatic way, like how you might feel speaking to the operator on the phone or finding directions. It’s all pretty convenient if you think about it, but I don’t like interactivity for that reason, it removes the viewer from their witnessing state and over-stimulates them.

'I never had large-scale art ambitions, mostly I had romantic ambitions of the life of an artist but once I left painting and moved into video art, I saw that an artist could be a kind of scientist and I had a rough plan of being a sort of cultural critic scientist, but never at this scale. It feels like this all just happened by accident. It’s one of those ‘don’t look down’ moments because once you do you lose your grip and fall to your death.'

So the way then that your sculptures perform, as it were, is that sort of how you think of them?

What do you mean by ‘think of them’?

I think I just anthropomorphised the work. Do you do that too? This is probably how robots will become sentient?

I try to bring the work where I feel it. Mostly it looks clunky and dull to me and I try to push it to become alive, or something other, but I don’t see it as alive initially, and I’m not tied to it emotionally – but maybe the results would be better if I were. It’s just hard, because I’m looking at everything so critically all the time, and everything must be activated all the time, and if it’s not, I’m frustrated.

How do you move past that then?

As an artist you have to reground yourself over and over again and simply find out what works and what doesn’t. It’s like every artwork has its own alphabet and you need to relearn and write a song or poem with it. Or, instead, maybe each artwork is like a broken car that’s delivered to you, and you have to invent a way to fix it. It’s endlessly difficult and annoying and demoralising. It’s insanely hard but the feeling of getting it trumps all the suffering and then in hindsight the suffering was really good.

So then is the ‘robot’ – that term feels not quite enough to describe it – an avatar for you, something other?

No, it’s not an avatar for me. I had these experiences with a stimulus that was moving from a very early age. And I probably have a kind of aptitude for things that move or making things move, for whatever reason, I don’t know. I remember when I was 11 or 12 standing on a small concrete river dam in Connecticut where I grew up. The water flowed over the dam so smoothly and perfectly it almost didn’t seem real, and I remember pushing my hand into the water and manipulating it, rolling over my hand, and I think I stayed there for an hour or so just making variations of this completely hypnotised by this perfect movement. It’s hard to explain but this was incredibly profound for me and either something woke up in me or something changed during this experience, and it has remained one of my strongest memories from being a kid. I felt it relate to me in a way before I knew I would be an artist and I still think about it all the time.

Jordan Wolfson, Body Sculpture (detail), 2023, National Gallery of Australia Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 2019 © Jordan Wolfson. Courtesy Gagosian, Sadie Coles HQ, and David Zwirner. Photo: David Sims.

In terms of the things that Body Sculpture does, can you talk a bit about those things and what you want it to do?

I guess looking back at it, the work kind of attempts to talk about how it feels to be a person and all the primitive qualities about ourselves.

The base level.

Right. You know that there’s a type of pleasure within us, instinctually, to be at once the audience and the performer. Like anything, it couldn’t exist without its opposite and needs to flip between the two. So, the artwork tries to show that. Good and bad, light and dark, and audience and performer.

Because the work literally points someone out, doesn’t it?

Actually, it doesn’t do that anymore.

It doesn’t do that anymore, okay.

No. We could have done that, but it just felt wrong. It didn’t feel right to do that. It felt interactive in a negative way.

As you were speaking about before.

I took that out, but that wasn’t something that I could anticipate being negative. I anticipated it being generative and then it was subtractive. If felt sticky and bad and blah. It was one of those funny moments where you toss out an idea you’ve been committed to for five years in five minutes because you just see it finally come together for the first time and it falls flat. I did get it to work in one way, but it ultimately wasn’t technically possible, so I made do and dropped it.

Your work is incredibly ambitious in scale, but is Body Sculpture different again from Colored Sculpture, for example?

They are relative in size actually. The thing is that I have this delusion that if I have an idea for something, then it must be possible, or some version of it must be possible. And, for better or worse, it’s this thinking that has led to this scale of production and complexity.

So, I guess then the question is does it match your original ambition? Maybe only time will tell.

I never had large-scale art ambitions, mostly I had romantic ambitions of the life of an artist but once I left painting and moved into video art, I saw that an artist could be a kind of scientist and I had a rough plan of being a sort of cultural critic scientist, but never at this scale. It feels like this all just happened by accident. It’s one of those ‘don’t look down’ moments because once you do you lose your grip and fall to your death.

This Q&A is an excerpt from an interview first published in VAULT magazine in November 2023.

Read the full version of this conversation online.

Jordan Wolfson: Body Sculpture is on display from 9 December 2023 – 28 April 2024.