In Plain Sight

Renowned art historian DR JANINE BURKE on the pioneering women artists who changed the course of modern art in Australia and whose work was the subject of a major National Gallery exhibition in 2023.

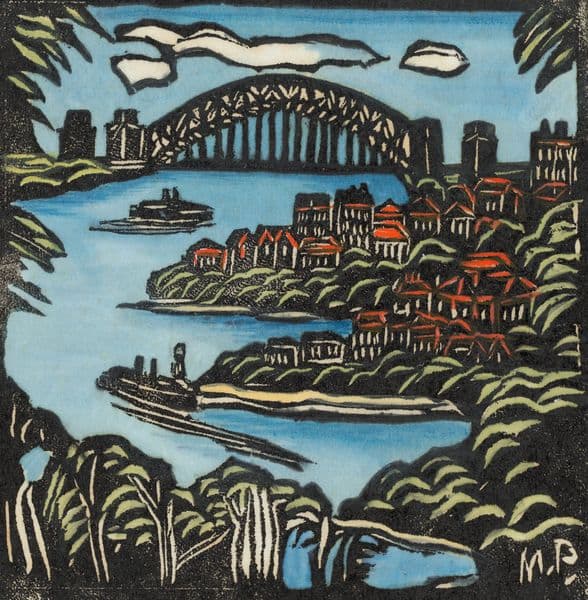

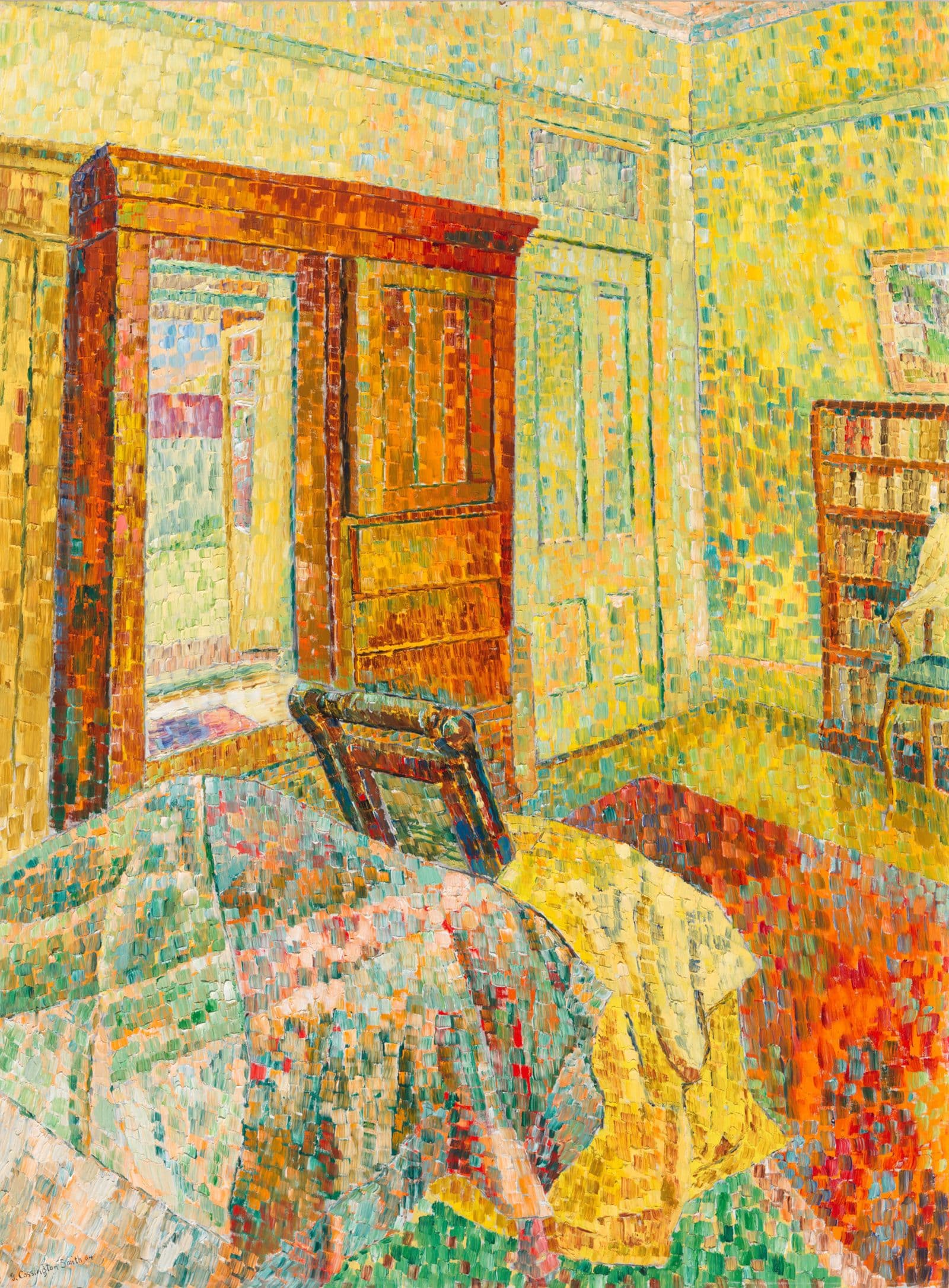

When Grace Cossington Smith was ‘discovered’ by the Art Gallery of New South Wales curator Daniel Thomas and made the subject of a big, brilliant, national touring retrospectivein 1973, a common — and startled — response was: ‘How is it we’ve never heard of her?’ And yet, Cossington Smith, who was born in 1892, had been hiding in plain sight for decades. She painted passionately and exhibited regularly at Sydney’s Macquarie Galleries. Founded in 1938 by Treania Smith and Lucy Swanton, it was something of a milieu for modernist women including Clarice Beckett, Dorrit Black, Grace Crowley, Margaret Preston and Ethel Spowers.

Cossington Smith’s quiet and fruitful, domestic suburban life with her sisters has been credited with protecting and preserving her talents, as well as being consonant with her own character. But, as Bruce James notes, it also contributed to her marginality ‘both critically and in terms of the perceived avant-garde. Her press notices were obliging, but few.’1

Unknown photographer, Grace Cossington Smith in the garden at Cossington, Turramurra c 1915, Collection of the Cultural Facilities Unit, ACT Government, photograph courtesy of Bruce James

Max Dupain, Portrait of Olive 1940, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1982

Unknown photographer, Portrait of Clarice Beckett, c 1931

Unknown photographer, Margaret Preston, aged 19 1984, photograph courtesy of the artist’s family

Photographer unknown, Portrait of Miss EL Spowers, a passenger on board the ‘Orama’ 1935, reproduction courtesy of The West Australian, Perth

Unknown photographer, Miss Eveline W. Syme, who is in charge of the library section of the Australian Red Cross Society, is seen displaying a typical parcel of books as sent out to hospitals, convalescent depots etc. This parcel contains about forty units, covering a wide range of literature 1943, reproduction courtesy of the Australian War Memorial, Kamberri/Canberra

In the 1930s, Ethel Spowers and Eveline Syme were innovative printmakers. Influenced by the design principles of Claude Flight, who taught them linocut at London’s Grosvenor School of Modern Art, they returned to Melbourne, where they set about galvanising the local printmaking scene. Spowers’ and Syme’s close friendship — neither married — together with their talents and travels, fostered a modernist female space. Their agency in that regard and their long-term support for one another is notable though not unique. While studying in France, Grace Crowley had the companionship of Dorrit Black. When Black founded the boldly named Centre for Modern Art in Sydney in 1931, Crowley was keenly involved. Prior to her marriage in 1919, Margaret Preston travelled and studied alongside ceramicist Gladys Reynell.

Only recently, Beckett has emerged as an admired and much-loved artist since 2021, she’s been the focus of a retrospective at the Art Gallery of South Australia, a biography and a major exhibition at Geelong Art Gallery. Beckett was ‘discovered’ — almost literally — by gallerist Rosalind Hollinrake. In the now well-known tale, Hollinrake was invited by the artist’s sister to view Beckett’s works which were stored in an open-sided barn on a country property near Benalla in north-eastern Victoria. Many were damaged beyond repair.2 In 1971, Hollinrake organised Beckett’s first major survey since her 1936 memorial exhibition. I recall viewing it at Hollinrake’s gallery — astonishing, accomplished, exquisite — and also the high prices set for the works. It was a wise move.

A negative aspect of women’s art was the low value accorded it. If their work was not regarded as having the same worth (in both senses of the word) as the men, did it have a pernicious effect on their ambitions? Cheaper prices in the cut and thrust of the art market often relegated women to the role of amateurs, judged as those who didn’t aspire to make a living from their art, together with the rider they weren’t good enough. It’s always challenging for an artist to survive; for women to establish their professional status has been even more difficult.

Even the notion of a ‘career’ was an anomaly for women. The word’s early meaning which describes a vehicle running out of control — ‘careering’ down a road — had become, by the nineteenth century, the description of a chosen profession which implied a steady onward movement. Women were not only discouraged to aspire to such lofty goals, but they were also usually denied access to them.

Class plays a significant role in the story of modernist women. Once upon a time, such women were regarded as dilettantes whose artistic skills would decorate the home of their father and then of their husband. Sunday Reed was a member of the prominent, wealthy, male-dominated Baillieu clan. She reflected in the early 1930s, as she was beginning her career as a champion of Modernism, that among ‘the men in our family … the prejudice is so strong and I quite understand that I’m never expected to say anything worth listening to and it would cause great annoyance if I did, so that I feel now I never want to — mostly fall into long silences’.3

Olive Cotton, Girl with mirror, 1938, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1987

Black, Crowley, Spowers and Syme left Australia to study, travel and explore. Unless Daddy opened his wallet, such adventures were impossible. Crowley discovered how abruptly the situation could change. In 1929, on the cusp of gaining recognition in her adored Paris, her father ordered her home to the family property at remote Barraba in the New England high country of New South Wales. Perhaps her family’s attitude to her ambitions is best exemplified by a story Crowley told Daniel Thomas: on her return home, she found her easel thrown on a rubbish tip.4 However, her father relented, and ‘Daddy’s gift’ allowed Crowley to return to Sydney.5 There, alongside her beloved companion the artist Ralph Balson, she became a key player in a small but vital avant-garde that privileged abstraction.

Modernism was not established, as it is now, in art history’s hierarchy. In the era between the First and the Second World Wars — when this group of artists was developing their mature work — it continued to be, particularly in Australia, reviled. It was ‘outsider art’ rather like the women who had committed themselves to it. Crowley believed that she was ‘shouldered off as one of those degenerate artists’, the Nazi Party’s term for modernism and which implied moral and/or racial inferiority.6

Amateur’ was an identity prescribed by an art world either indifferent or hostile to women’s cultural production. ‘Invisibility’ was its twin, its curse — an aura that continues to surround and obscure women. Otherwise, why the surprise when they are ‘discovered’? For these women, being an artist was a driving force, a desired identity, often more compelling than marriage or children. Some also spent many years as students.

Did the time of wandering and studying assist in keeping them away from the pressures of home, family and marriage? Spowers spent 20 years studying art until her modernist awakening in 1928. Syme, after an impressive — and for that time, very unusual — academic education from 1912, began art studies in 1922. She began exhibiting in 1930, by which time she was 42. When Spowers died in 1938, so did Syme’s art — she produced only four more linocut prints though she lived for another two decades.7 It’s a touching though melancholic tribute to their art’s mutual dependence and inspiration.

What of Beckett? How did she manage her art/life? She died of influenza at 48, after a life devoted to painting and, later, to the care of her ill and ageing parents. Beckett’s father, something of a domestic tyrant, possessed neither the funds nor the will to provide his daughter with a studio. The kitchen table would have to do.8 While it sounds like the sad tale of a dutiful daughter, the attention Beckett now receives indicates there was no diminution of her powers. Beckett’s apparently dreary suburban existence made a place for art of the highest calibre.

Grace Cossington Smith, Interior with verandah doors, 1954, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, Bequest of Lucy Swanton 1982.

Since the 1970s, it’s often been due to the interrogations of alert women curators and historians (and their feminist-friendly colleagues such as Daniel Thomas and Bruce James), that these women have been recognised as a group, an influential cohort who, despite their relative ‘invisibility’ on their return to Australia, nonetheless impacted art and helped to modernise it.

To write about women artists is to write biography because of the politics of sex and class that govern their destiny. It’s one of the notable ways that feminism has changed — and continues to challenge — art history. The personal remains the political.

In 1975, I curated Australian women artists, one hundred years: 1840–1940, a national touring exhibition and the first survey of its kind. Aside from Reynell, every artist mentioned in this essay was represented by several works. Yet the task to ‘discover’, to make visible and to assign status continues.

Grace Cossington Smith and Margaret Preston are included in the Know My Name: Australian Women Artists national touring exhibition which begins at Mornington Peninsula Regional Gallery in November 2023.

Clarice Beckett is on display in the Clarice Beckett national touring exhibition.

This story was first published in The Annual 2023.